City Portrait

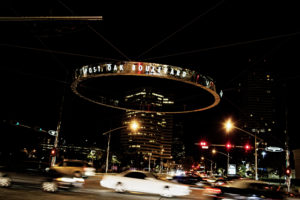

Houston, Texas

Through busts or booms, Houston has always looked forward. And today, from food to fine art, the biggest city in Texas is humming

In the spring of 1987, my editors at U.S. News & World Report sent me to Houston to get the reaction of that city’s elite to a recent front-page piece in the Wall Street Journal. The city was still reeling from the oil bust, and the paper painted a grim picture—there was mention of a suicide, I think, as well as a description of a downtown so empty tumbleweeds might any minute be blowing through it.

I’d barely landed when my good friends George and Nancy Peterkin whisked me off to the Contemporary Arts Museum’s annual fund-raising gala. On the plane, I’d studied up by reading a pile of clips from the Houston Chronicle, one of which talked about the effect of the bust on the city’s arts community: “It was the year the city bit the tarmac economically, but…there is no sign that anyone has turned in his track shoes.” The CAMH’s Balinese Ball was definitely a case in point.

There were Balinese dancers, models painted gold, and more orchids than I’d ever seen in my life. The invitation had said something like “sarong optional,” and a great many of the well-toned women of Houston did, in fact, opt—combining artfully arranged bits of brightly colored silk with boatloads of diamonds. One woman whose brand-new ten-carat ring was for “ten years of marriage, honey,” said she’d been so upset by the WSJ article—which she’d read a couple of days earlier on an Aspen ski lift—that she’d skied right off the mountain and flown directly home. It was the tumbleweed thing that had gotten her—lest anyone think the city was actually empty, she was duty bound to come back and add herself to the number of good citizens who were ready to stick around and fight in the face of adversity and, more important, bad press.

I had known my own story would write itself, and I’d also known I would find a populace raring to get back on its feet. Barely two years after my visit, a snarky piece about how the Houstonians had already managed to mythologize the bust, which they “served up larger than life,” appeared in the New York Times. “The latest lore shapes up like this: The bust was a trial for Texans, who showed they could take it when it could have killed folks from a lesser state, and they came out of the experience better and stronger than ever.”

The writer was clearly not from Houston—otherwise she would have known that the “lore” would prove to be pretty much on the money. Today, the city is the fourth largest in the country, but it may well become the third largest on the watch of the new mayor, Annise Parker, a popular former city councilwoman who is the first openly gay mayor of a major American city. Although Houston did indeed lose more than two hundred thousand jobs during the 1980s, it is once again a thriving capital of the oil and gas industry, and its port now ranks first in the nation in international commerce.

The city is also home to NASA’s Johnson Space Center as well as the Texas Medical Center, which contains the world’s largest concentration of research and health-care institutions—forty-nine not-for-profit entities in all, including the MD Anderson Cancer Center, the Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children’s Hospital. Established with a 1939 gift from Monroe Dunaway Anderson, who formed a foundation so his estate would not have to pay the taxes he feared would dissolve his cotton company (also, naturally, the world’s largest) after his death, the medical center has been home to the world’s two preeminent cardiac pioneers, Michael DeBakey and Denton Cooley, and its growth continues apace.

Photo: Jody Horton

Local Energy

Chef Robert Del Grande and friends at RDG + Bar Annie.

The same breathtaking largesse is found in the cultural arena. At a time when major museums in other cities are either closing or struggling, Houston’s continue to flourish. DiverseWorks, a contemporary arts center whose mission is to present new visual, performing, and literary art, proclaims itself “distinguished” from similar centers around the country by its “financial stability.” The Museum of Fine Arts has a new director, Houston native and Met veteran Gary Tinterow. One of his first jobs will be overseeing the construction of a new building to house the museum’s collection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art.

The Museum District, an association of eighteen wildly diverse museums and galleries, attracts around nine million visitors a year, and it doesn’t even include such notable spaces as James and Ann Harithas’s Station Museum, the Orange Show, or the enormous breadth and depth of the city’s commercial gallery scene. “Houston has the sharpest, most vibrant art scene in the country right now,” says the artist John Alexander, who began his career there.

The art scene is by no means the only bright spot on the cultural map. Houston has permanent companies in all the performing arts disciplines, and then there is an entirely different sort of culture in the form of the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, a twenty-day annual event straddling February and March that is the largest of its kind anywhere in the world.

It is the juxtapositions of things like, say, the livestock show against the Balinese Ball that defines the place. Houston is what you might get if you took everything that is really, really great and slightly irritating and crazy in a good way about the South and about America and threw it in one of those rock-polishing tumblers for a spin or two before dumping it all out and leaving everything where it lay. Unlike most of Texas, there’s almost as big an African-American population (more than 25 percent) as there is Hispanic. Houston’s location on the Gulf attracted two different waves of Vietnamese immigrants (the first were largely shrimpers), which means there are some great Vietnamese restaurants, and its close proximity to Louisiana means that Cajun- and Creole-influenced cuisine comes close to rivaling Tex-Mex and barbecue. It is entirely Southern in its graciousness, but decidedly un-Southern in that it is almost devoid of the habit of looking back.

Photo: Jody Horton

Big Fun

One of the Menil Collection’s varied exhibits.

Houston is also the only city remotely close to its size in the country that has no zoning. So instead of one mandated central business district, for example, major clusters of commerce are spread all over town, with leafy residential areas, huge parks, and lots of shops and bodegas and art galleries and check-cashing services and whatever else thrown in between. All this means that whatever you need—one of the forty thousand different labels of booze or wine at Spec’s, a spiffy and extraordinarily speedy car wash at Dr. Gleem, or a four-dollar margarita from La Mexicana—is almost immediately at hand. You can see some highly charged political art at the Station Museum or enjoy an afternoon of quiet reflection at the Rothko Chapel; you listen to blues in a gritty club or dress up for a night at the opera.

Whatever you choose to do, people will generally be really nice to you. Houston is all about enthusiasm and service—the traffic might be terrible, but you’ll be happy when you get where you’re going. There’s live music while you grocery shop, after all, white wine while you try on shoes at Tootsies. The fur man at Saks is so persuasive he almost convinced a friend of mine and me to go in halves on a chinchilla stole neither of us could afford. He draped it around us, he gave us champagne, he pronounced fake fur “so unwonderful.”

Which leads us back to the top and my CAMH friend with the ten-carat diamond. Well-heeled Houstonians are not afraid to show off their very real furs and their very large rocks, but when they say bigger is better, they follow through. The city has always been known for its socialites (think Joanne Herring, who funded Charlie Wilson’s War, or Lynn Wyatt, whose sculpted arms are by now a local landmark), but even the silliest among them rally behind the institutions so important to the life of the city.

The night I was there twenty-five years ago, despite the dire assessment of the Wall Street Journal, the CAMH made a lot of money. In my own article, I reported that the bust had not dimmed the spirit of the citizenry and would likely be but a speed bump on the city’s historically forward-looking road. It’s like what an executive told the woman from the Times: “We did get our comeuppance. But we didn’t whine about it, and I think the rest of the country respects that. Other places would have had an ‘oh me’ type of attitude. I never did hear that down here.”