Food & Drink

Family Style

Each year, for four decades running, one extended Texas clan comes together on the land they love, in the name of food, fellowship, and teaching the youngsters a thing or two about what really matters

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

“Didn’t even get the fire going right,” says Harold Mabrey, referring to the two men toiling away at the pit over by the chicken coop. Too much smoke is billowing from the chimneys. Flames are flaring up. “What you do is drench the cold ashes in there with lighter fluid and wait ten minutes,” Harold, who is eighty-two, explains. “Then you put the briquettes in, drench and light those. Wait fifteen minutes. Then you got yourself a cooking fire.” Two other men—Morris Henry Peoples, who’s seventy-seven, and Carold Peoples, eighty-two—nod gravely. You can’t do anything without a good fire. Which the young men working the pit would know if they had a lick of sense. In truth, these men aren’t exactly wet behind the ears. Phillip Cummings is in his early sixties, and Eddie Peoples isn’t far behind. But because they are not of the elders’ generation, they are, by definition, all but devoid of common sense.

I’m sitting with the three elders in white plastic lawn chairs in the shade of a sweet gum tree on Morris Henry’s farm. Around us, a half dozen pickups are parked tail first and gates down, each with a cooler full of soft drinks, beer, and water. Three of Morris Henry’s grandchildren, amped on sugar, do flips on the trampoline. Younger men come and go. There may well be women in Morris Henry’s house, but there’s a big shed between us and the house and we don’t see any. The barbecuing has always been men’s work. Before the annual Peoples family reunion tomorrow, the guys will crank out 180 pounds of ribs and 45 of chicken. There will be brisket, too, but that’s being done by a cousin somewhere else. There isn’t room for brisket here, despite the size of the four-station pit, cut and welded from two big propane canisters. The reunion has been going for about forty years and draws a hundred or so members of the extended clan—the Peoples, Cummings, and Johnson families being the major branches—to Pittsburg, in northeast Texas. This year the meal is being held in a rented community center, where a sign warns that you lose your deposit if the police are called for any reason.

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

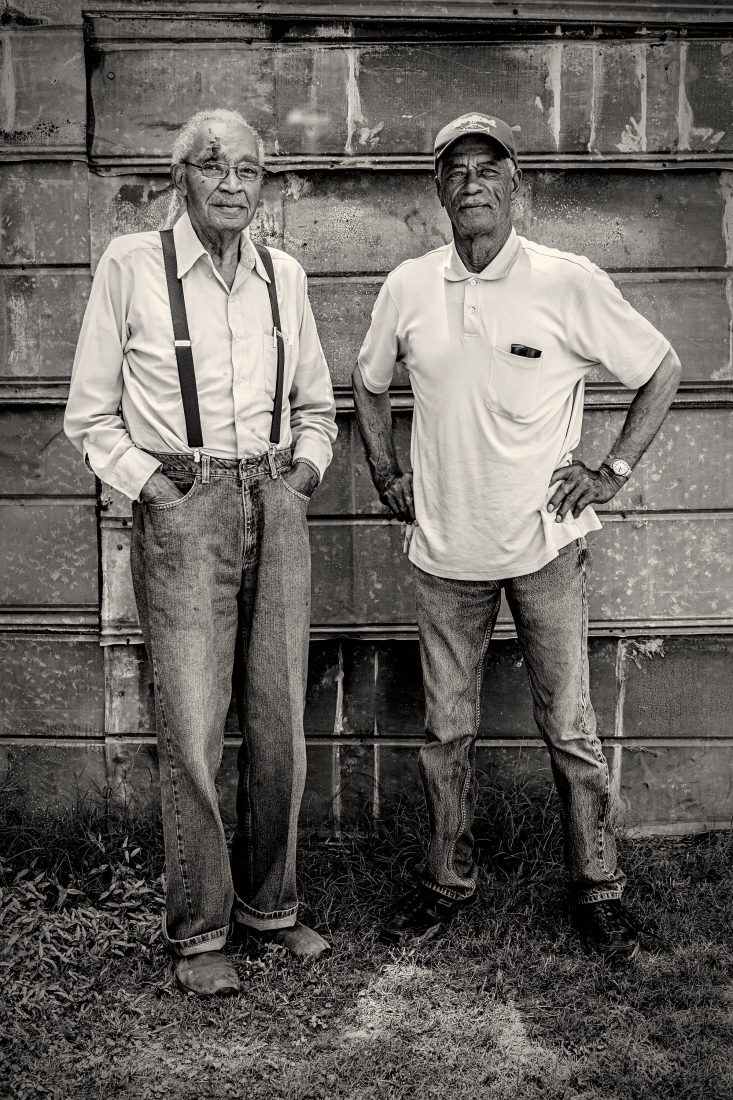

All In The Family

Elders Harold Mabrey and Morris Henry Peoples.

A number of the family came down on Wednesday to prepare for the Saturday meal. A bunch of us spent hours yesterday trimming and seasoning the ribs on folding tables, circling and sprinkling the racks with at least a dozen spices, FedExed here in a large box days ago. It felt like some strange ceremony, bottles in each hand sifting magic dust onto the meat. We sprinkled Old Hickory Smoked Salt and cayenne, paprika and onion powder, Beau Monde and Lawry’s Seasoned Salt, and at least that many more. When I went to pee, one of the younger men warned, “Make sure to wash your hands before,” to general murmurs of assent. “Found that out the hard way last year.”

The elders—three first cousins, as close as brothers—grew up on this land more than seventy years ago. They’d rather be here right now than anyplace else on earth. They were four until a month ago, when Marvin Cummings, Phillip’s father, passed just shy of his ninetieth. Harold is said to have taken it particularly hard. As if by unspoken agreement, no one mentions Marvin. For that matter, no one knew for sure whether Carold, who lives in Denver and is in less-than-perfect health, would make it. When the two others saw him approach in a pickup, they immediately rose and smiled. Before Carold had even come to a stop, Harold called, “Where’d you steal that truck?”

They don’t appear busy, but they are, fulfilling the duties expected of elders since the first reunion. This, near as I can tell, consists of remembering their youth, lamenting the ever-steeper decline in common sense among the young, and, most immediately, keeping the knuckleheaded young men doing the actual cooking on task.

It’s the elders’ job to see that the cooks do theirs correctly. The fire, for instance, requires constant vigilance. It alternately requires stoking, lest it go out, and choking, lest it flare up. Judging the coals, timing the putting on and taking off of meat, when to add green hickory to the fireboxes and in what amount—all this must be done properly. When the first batch of ribs comes off, shreds of meat will be presented to the elders on plates so they may pronounce its fitness. Above all, throughout the day, the elders will repeat the mantra as it was repeated to them, the first and last commandment of barbecue. “Don’t burn the meat.”

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Tools of the trade.

Over at the pit, the younger men are living up to the elders’ expectations. The fire is still burning hot. “Open those fireboxes,” Harold calls. “Squirt some water in there.” Eddie Peoples retrieves the hose, hooked by its nozzle onto the coop’s wire fence, and squirts. The smoke lessens instantly. But everyone knows it’s just a temporary fix.

The charcoal nearest the firebox caught fine, Phillip explains. The problem is, it won’t spread to the briquettes at the other end. He’s wearing gloves and an apron, a towel slung over one shoulder. The heat is staggering. If you’re on the upwind side of the pit, you’re fine. But where Phillip is standing, the smoke is overwhelming. You really need one of the better OSHA-rated respirators, preferably with replaceable filters. The two canisters are welded together and have intricate iron curlicues connecting the two chimneys, rather like a very small version of the kind of fence you see around old graveyards. The pit is mounted on a trailer whose tires are sunk half an inch deep into the hard ground. It hasn’t moved in a long time.

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Heat Check

Phillip Cummings keeps the flames at bay.

After a few more minutes of trying to redistribute coals to get the uncooperative briquettes on board, Phillip’s frustration gets the best of him.

“Where y’all buy this sorry-ass charcoal?” he asks loudly.

“Walmart,” Harold says placidly.

“What kind is it?”

“House brand.”

“We need charcoal that works,” Phillip says. “Kingsford cost a bit more but at least it works. This stuff won’t even catch.”

“Don’t need expensive if you know what you’re doing,” Harold says imperturbably.

“If you know what you’re doing, you know cheapest not always best one to buy,” Phillip retorts. Harold’s face remains impassive. Phillip, as if realizing he may have come close to contradicting an elder—something you do not do—goes back to his fire.

“Don’t burn the meat,” Harold calls.

The elders are worried about what comes after them. The thing they most want their children and grandchildren to understand is that the land is more than land. The seventy-five acres that Allen Rutledge, born into slavery in 1841, and his son-in-law Tom Peoples acquired—no small feat for black men in Texas shortly after the Civil War—is everything. It’s the outward and tangible sign of an inner and irreplaceable heritage. It’s where the family comes from, who they are, how they have created, sustained, and affirmed themselves for 150 years. Money lights up and vanishes as quick as a firefly. It leaves nothing behind. Land is eternal. I try to imagine what it must have felt like for a black family at that time at the moment they took possession of a parcel of ground. It must have been miraculous. Owning land meant escape from the endless cyclic poverty of sharecropping. It meant a livelihood and conferred standing in the community. A man couldn’t vote unless he owned land. Of course, if he were a black man, he most likely couldn’t vote anyway. But neither could he be so easily dismissed as a man who had no property. And the sacrifice to get it and blood and sweat that had gone into working it for generations meant something and was worthy of safekeeping. Some of the young people understand that. The ones around the ribs and chicken seem to. But they’re the ones who tell me that an increasing number of their peers, who inherit ever-smaller parcels as their number increases, have no interest in their five acres. They’d rather have the money.

At last, Phillip and Eddie pronounce the fire ready. The first ribs go on and the doors slam shut. Morris Henry—his first name is Morris, but nobody calls him that—retrieves a stepladder, leans it against a hickory, and climbs up to cut boughs. He has bright blue eyes. He is lean and hard from a lifetime of getting up at 5:30 to work. Today he is dressed up, wearing a polo shirt over an undershirt. Yesterday, he wore a denim shirt whose collar and left cuff were worn into something more like lace than cloth. But Morris Henry is a farmer, and the shirt still worked. Seeing the elder climbing, a number of young men rush over to help. Morris Henry, looking irritated, shoos them away. “Where y’all when there’s real work to be done?”

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Inspecting the ribs.

A while later, Phillip calls me over. He explains that you cook ribs mostly by color. “You want the tips, the bone, to change from tan to brown. And the top, where the meat’s the thickest at the center? You want that dark red with just a little bit of char on it.” He flips the racks, and we’re both overcome by smoke before he can explain about the underside. “Why y’all cryin’?” calls Wayne, Phillip’s older brother.

“You come over and I’ll give you some of this hickory smoke,” Phillip says. “See if you don’t cry.”

Wayne is six foot four, with smooth brown skin and pronounced American Indian features. He is one of the recently deceased Marvin Cummings’s six children. Marvin spent thirty years in the army, retiring as a sergeant major. When he learned that Wayne intended to enlist and go to Vietnam, he got himself posted to a desk job there in the hope that Wayne would not also be sent. Wayne enlisted anyway, asked to be assigned to the infantry so he wouldn’t miss out on the fighting, and went to Vietnam. After the war, he became an army ranger, one of the guys who jump so low over their targets that they joke they don’t really need parachutes. Then he became a sniper. He rode bulls on the rodeo circuit for a dozen years. Now he’s married to a former school principal and teaches geography in a public school for children with discipline problems. On weekends, he used to compete in high-level country-and-western dance competitions, wearing braces on both legs under his jeans. He wears his yellow-gray hair in a ponytail under a cowboy hat with a turkey feather in the band. Wayne is a commanding, extroverted guy, a genial badass.

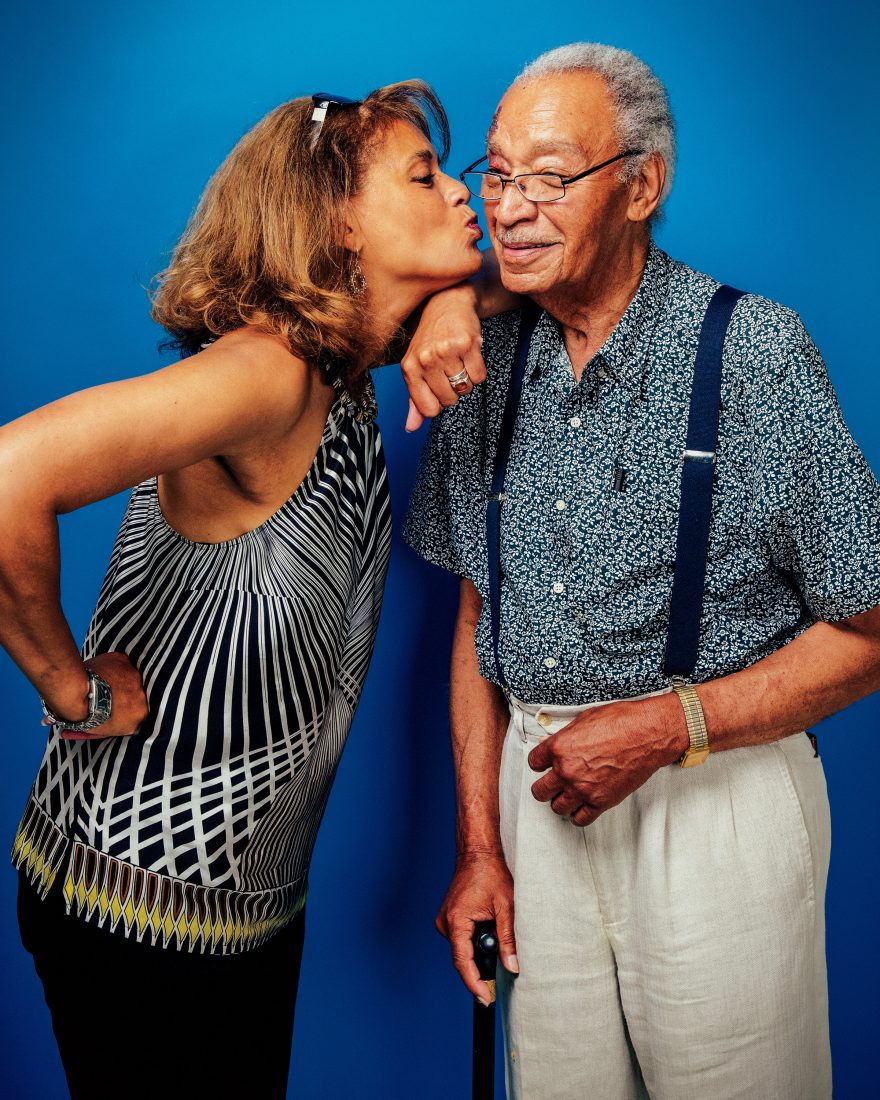

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Vicki Mabey and her father, Harold Mabrey.

Vicki Mabrey, Harold’s daughter, is doing her daughterly duty, which is to watch over Harold. She flew from New York and met him in Dallas, where he flew from his home in St. Louis. Her mother doesn’t come to the reunions because, after more than half a century, some of the family still haven’t gotten over her taking Harold out of Texas. Vicki is an Emmy Award–winning former journalist, a veteran of 60 Minutes II and Nightline. Driving with Vicki and Harold the other day, I asked if the South felt more racist than other parts of the country. Vicki said she has never felt comfortable in the South. Harold said, “Malcolm X said that the South is anything south of the Canadian border.” When I told Harold, a creased-blue-jeans-and-suspenders kind of man, that he’s the last person I’d expect to hear quoting Malcolm X, he smiled. “Oh yeah. I used to keep up.” Harold administered the civilian side of army contracts for more than thirty years, negotiating everything from two-cycle engines to Apache attack helicopters.

Now Vicki ventures over to the elders to tell me that on the way out from the hotel this morning, they passed a neighbor’s field that Harold used to plow. “What did you say, Dad?” she asks. “Ten hours a day at fifty cents an hour?” Harold nods. “And so you plowed with, what, a tractor?”

Harold shakes his head. The child might as well have said “spaceship.”

“We didn’t have a tractor,” he says. “We plowed behind a mule or a horse.” The two other men nod.

“And you ’member that hot sand on the road?” Morris Henry asks. “That sand burn your feet so bad you’d start hopping. Looking for anything to cool ’em—bit of shade, some grass, a bush to stand on.”

“Yeah, a bush be good sometimes,” Carold murmurs.

Vicki cannot process this. “Wait. You didn’t wear shoes?”

“Oh, we wore ’em to church,” Carold says. “Say, y’all remember that little church by the two-room schoolhouse near the cemetery? Had a circuit preacher, Reverend Bowleg Johnson. ’Course, we didn’t call him that to his face.”

Harold nods. “Used to have a lot of bowlegged people in Pittsburg.”

Vicki can’t let this go. “So you had shoes but you didn’t wear shoes? Why not?”

Harold’s eyelids close halfway and reopen. He answers very slowly. “To save the shoes.”

Vicki shakes her head and goes to fetch her father another bottle of water.

Harold has the timing of a master comedian. One of the younger men asks Morris Henry how many children he has, and in the beat before he can answer, Harold mutters, “Aw, he don’t know,” cracking everyone up.

At last, Phillip pulls the first racks off the fire and plunks them down in a metal pan. Wayne cuts slivers with his pocketknife onto a paper plate, walks over, and holds the plate out to Harold. Harold takes a sliver and chews slowly, a fifteen-second eternity, his face a perfect deadpan. Phillip can’t take it any longer. “Well?” he calls from the pit. “How is it?”

Harold continues to chew for a while. Finally, he gives a short nod. “All right,” he says.

Everyone laughs. “That’s like getting five stars from anyone else,” Phillip says. “I’ll take it.”

The next day the community center is abuzz. The women have shown up with their side dishes, biscuits, and pies. Phillip has another pit going, a single propane canister but otherwise almost identical to the first pit. Before the ribs go on to warm, they’re coated with a sauce made from the following: the brown-sugar kind of Kraft barbecue sauce, ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, apple cider vinegar, French’s mustard, chili sauce, chili powder, paprika, lemon juice, black pepper, onion powder, and garlic powder. It is sweetened to taste with white sugar. The resulting two gallons is thick and intended to be thinned to at least twice that with Coors beer.

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Let's Eat!

Harold Mabrey, Myrdis Peoples, and Alice Cummings Hill at the family meal.

It’s hot outside and cool inside the center. While it’s tempting to go inside for relief from the heat, this is a delicate business. A loitering man is fair game for the women to put to work. I’ve already had to transport and break up bags of ice, carry coolers and cases of soda and water various places, and move chairs. I’m staying out.

One of Morris Henry’s sons, Marlon, is drinking a beer by the pit. When I first saw him, with a scraggly beard and shorts that extended to his shins, he had hip-hop blasting from a brand-new cherry-red pickup. He tells me that he had studied computer science on a football scholarship at the University of Arkansas. When he got injured, the scholarship went away. Until fairly recently, he worked in the Louisiana oil fields. It paid well but he didn’t see his three children as much as he wanted. He has custody of them. He took a truck-driving job to be with them. He lives at his father’s house so his parents can help take care of the kids while he’s working.

I ask Marlon what he intends to do with whatever land he inherits. “Keep it,” he says simply. “You kidding? I know all the blood, sweat, and tears that went into it. I been around my dad and these men all my life. Learned a lot from ’em. I cherish every moment with these men. Every moment. And seem like you lose another one every year.” With that he goes inside to carve the brisket.

Photo: LeAnn Mueller

A prayer before the meal.

The meal itself is anticlimactic if you’ve been cooking, breathing, and tasting it for two days. There are vegetables and salads and casseroles of every description, each with a woman and a serving spoon behind it. Wayne, naturally, is the one who quiets the room so someone else can say the prayer. We go through the line in order of seniority, elders first. When it’s my turn, one of the matrons at the dessert table says, “Would you like a piece of my egg pie?” in a way that is anything but a question. “Yes, ma’am, I would,” I reply. It is, in fact, delicious, custardy and sweet with a terrific crust. I go back for seconds. I notice that Wayne, without saying anything about it, waits until every person has been served before he fills his plate. It’s not forced, not for show. It’s his default setting, what a leader naturally does. Wayne is a young sixty-three. But time is sneaky. In a decade, quite possibly less, he’ll be an elder. I’m cheered by the thought. Maybe the family’s future isn’t nearly as shaky as the elders would have you believe.