Sporting

Fishing Georgia’s Satilla River

During the peak of the summer redbreast bite, an entire subculture springs up on the shoulders of a small yet pugnacious—and stunningly beautiful—fish

Photo: Tim Romano

The author (right) and Bert Deener work the waters of the Satilla River for redbreasts.

You’ll find them haunting creek banks and dark river coves where blossoms of shadbush and wild blueberry swirl through old cypress trees. That’s where the fish flash like iridescent lightning. Redbreast sunfish live in places that call to childhood memory and sandbar naps. Until you hook one on a cricket or a curly-tailed grub. Then you don’t think so much about how things used to be because you can feel the fight all the way down the rod and into the palms of your hands, and what you think about most is putting such a bellicose fish in the boat.

These fish sport a blue-green back and rays of turquoise around each eye. During the spring and summer spawn, the males take on a red hue so brilliant it gives them the nicknames “redbelly” or “robin” or “rooster red.” Most prevalent in lower Piedmont and Coastal Plain rivers and creeks from Virginia to Mississippi, redbreast sunfish live in waters where the South’s natural fabric is largely intact. They are the brook trout of the South’s overlooked blackwater rivers and Piedmont creeks, the redfish of our cypress sloughs and bottomland forests.

This is a creature that ties human and natural history together in a region of the South that few explore. Up and down the South’s redbreast rivers, old fish camps still hang on in the woods. Anglers thread trailers down sandy boat ramps to drop jon boats and canoes into the water. Jimmy Carter wrote of wading waist-deep on the sandbars of the Little Satilla River, his favorite redbreast fishing stream. It was “a remote and lonely site,” he recalled, which led him to stay close to his father as they waded the dark waters.

Photo: Tim Romano

A redbreast in hand.

“This little animal captures the vibe of what this ecosystem means to so many people,” says Flint Riverkeeper Gordon Rogers, a son of the Georgia Coastal Plain soils. “It’s a piece of flypaper that all of the emotion and memories and hopes of this landscape sort of grab on to.”

Last summer I spent a week along Georgia’s Satilla River, perhaps the center of redbreast fishing culture in the South. I fished with historic old fishing clubs and lure makers and scientists, and paddled and camped on remote sandbars as white as a Bahamas beach. Undammed for its entire 235-mile journey across the state’s Coastal Plain, the Satilla is a place where people work hard to keep the culture of redbreast fishing alive—and keep the natural state of this river intact.

Photo: Tim Romano

Winge’s Bait & Tackle.

And it’s a region loaded with unforgettable characters. On my first morning in Georgia I stopped by Winge’s Bait & Tackle, just outside downtown Waycross, to load up on gear and a fishing license. Richard “Dickie” Winge’s father opened the store in 1954 in a bygone Gulf gas station across the street. It’s been the region’s go-to tackle shop ever since. There’s a steady stream in and out of the shop on a weekday midafternoon. “You can tell it’s getting right,” Winge said, grinning. “Full moon last week, and this warm weather is doing it.”

“It” is the fast and furious fishing of the redbreast spawn, and I loaded the checkout counter with popping bugs, hooks, and corks. Winge, however, wasn’t convinced that an outsider had what it takes to compete on the Satilla. He walked me out to the front parking lot with an eleven-foot-long collapsible BreamBuster pole. “That rooster is just so ferocious when he hits,” he told me, smacking his hands together for emphasis. “It will zip the line through the water, and you can hear it just a-singing while you’re trying to hold on. But first we got to get you buggin’.”

Photo: Tim Romano

Richard “Dickie” Winge shows off a BreamBuster pole.

He pointed to a curb in the parking lot, and flicked a red popping bug up against the concrete. “That’s the riverbank, see?” he explained. “And you got to get right next to it. Not four inches away from it. Next to it. That’s where the big roosters live.”

He whipped the rod overhead. “Look at how I snap this thing,” he admonished. “And you’ll have to sidearm it or you’ll spend half the day picking your bugs out of the branches.”

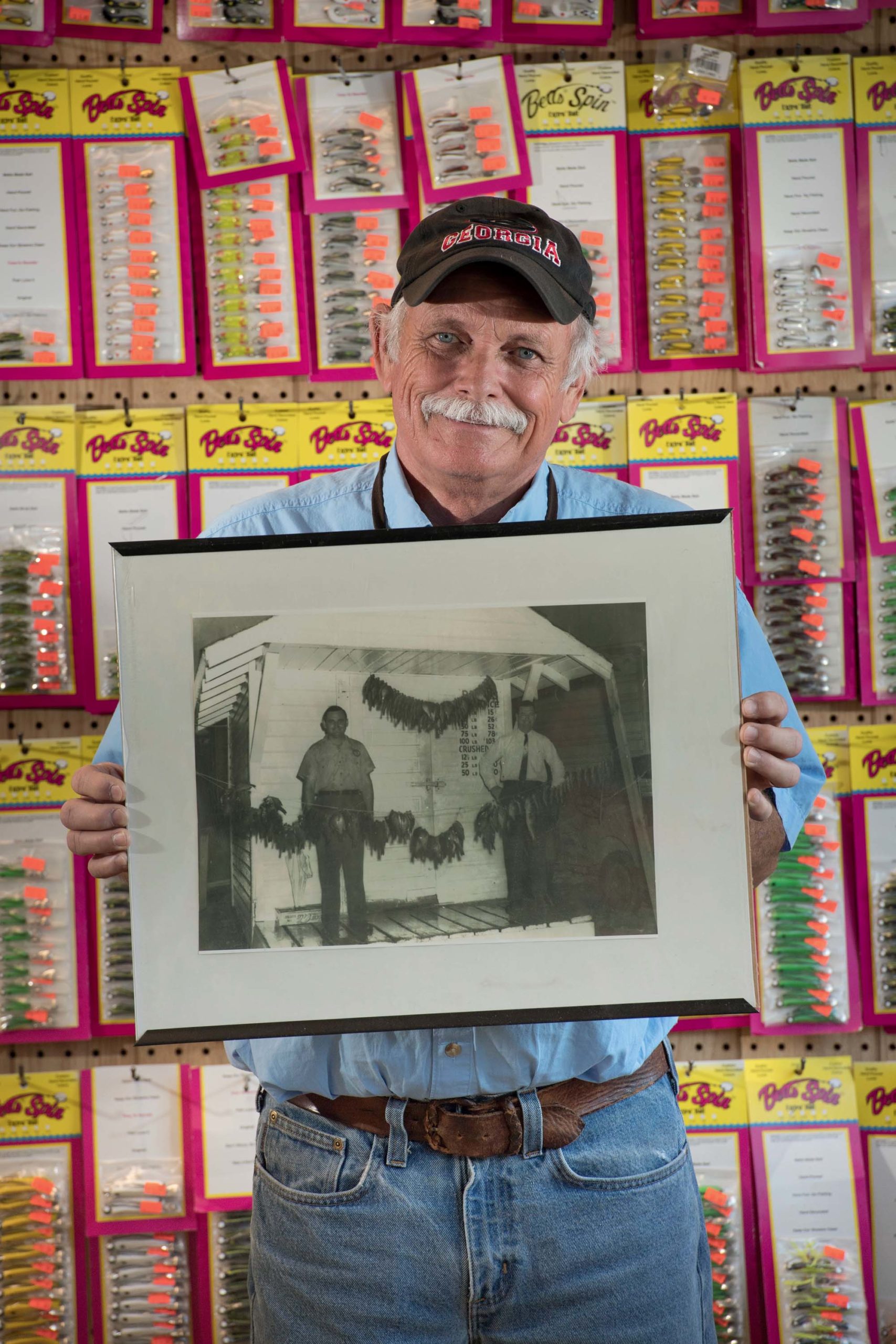

Photo: Tim Romano

Winge at his store.

He handed me the twenty-two-dollar pole, and I thought about the three thousand dollars’ worth of fly rods and fly reels stashed in my truck. I flicked the bug over my shoulder and snapped it forward just as a timely breeze picked up at the perfect moment to help me lay the bug not a half inch from the curb.

“Oh, yeah, boy,” he said. “You gonna do just fine.”

Like most Coastal Plain streams, the Satilla River ecosystem is driven by late winter and early spring floods, which spread the river out into wide swampy floodplains where fish leave the river to feed on a smorgasbord of ants, crickets, worms, and small baitfish. When the water recedes, the fish return to the main river course, fattened by the nutrients of an entire riverine landscape.

Photo: Tim Romano

Crickets for sale at Winge’s.

“If you don’t have high winter water, you won’t have good fish,” explained Bert Deener. Nor good fishing, and Deener is concerned equally with both. A fisheries biologist for Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources, Deener is also the inventor of the Satilla Spin, one of the deadliest lures for redbreast, and the maker of an entire arsenal of other artificial baits.

In his jon boat one afternoon, on the Satilla River below Nahunta, Georgia, Deener played the trolling motor’s foot pedal like a church organist, bumping the boat with little bursts of energy so it caught subtle river eddies to place him in a precise casting position. To watch Deener cast a spinning rod is to witness an elite athlete in peak form. He fired a small safety-pin spinner underhand, with a tight circular backcast to bring the rod tip low. The lure shot thirty feet across the black water, as straight as a missile. It slipped under an overhanging cypress branch with maybe two inches to spare, rocketed over a downed tree, then threaded a hole in the brush not half the size of a basketball to land in a cereal-bowl-sized clearing in the water. It was as skillful a cast as any I’d ever seen.

Photo: Tim Romano

Deener loads up.

My casts weren’t as on-target, but I still managed to put a Satilla Spin in the right place a few times. Deener and I traded fish. We pulled in piddling-sized redbreasts, a small largemouth bass, a stumpknocker—the spotted sunfish, which hangs around submerged trees—and then suddenly Deener’s rod bent double and the reel zinged as a serious fish took off for the dark timber.

“Oh, yes, come on in the boat!” Deener cried. “That might be what we’re looking for.”

The fish never gave up the fight, the rod plunging like a dowsing stick with every run, and when he brought the rooster out of the water, we all gasped at the brilliant red breast. It was a solid ten-inch fish. Bragging size if not large enough to get our names in the local paper.

“He might not be the boss of the river,” Deener said. “But he was sure boss of that log.”

We took a few photographs of the redbreast, and then I released it as if it were a wild native trout: I leaned far over the gunwale, cradled the fish in my hands, moving it gently back and forth to wash the river through its gills as it caught its breath. Deener watched from the back of the boat. “There aren’t many prettier fish,” he crooned. “I know fish. And there’s just not.”

Photo: Tim Romano

Catch of the day.

The Satilla winds through big timber and farm country and long stretches of low ground clad in cypress swamp. There’s precious little public access, which helps explain the presence of the historic fishing clubs and camps that hide along its banks. Many have moldered into the tupelo gums and pine flats: Gone are Long Lake, Happy Hollow, Nimmers Camp, and Blackshear Fishing Club. But at least three other old-time fishing clubs still operate, and their decades of history reflect every cultural, social, and political aspect of the river’s native redbreast sunfish.

One afternoon I met James “Jimmy” Stewart III at the Waycross Fishing Club, downstream of the Highway 52 bridge. The club was founded in 1917 on a strategic river bluff, about as far as folks from Waycross could drive, fish a bit, and then get home that same night. Memberships are handed down across generations. Waiting lists can be decades long. Among its members are the owners of the Waycross newspaper, local bankers, a large insurance family, and the founders of Red Lobster and Olive Garden.

Photo: Tim Romano

A sign for the Waycross Fishing Club.

Stewart sported a few days of salt-and-pepper beard stubble, eyes shaded with a camouflage sun visor and round eyeglasses that ride up his nose when he laughs, which is often. He’s the third generation of leadership at Stewart Candy Company, which has grown from its 1922 roots as a maker of peppermint candies to a distributorship that fills the shelves of half the convenience stores in South Georgia. And he’s the third generation to hold membership in the Waycross Fishing Club.

The clubhouse is perched on a high bluff overlooking Buffalo Creek, a dead-end slough off the main stem of the Satilla so wild and pristine that I half expected pterodactyls to fly through the woods with the pileated woodpeckers. It’s nothing fancy, a sprawling low building with a massive great room and a wide screened porch overlooking the main attraction: a small-gauge two-track trolley with an open car that ferries anglers up and down the steep bluff. It was built around 1950 as trolling motors started replacing oars, and members tired of lugging heavy batteries up and down the hill.

Stewart and I clambered into the trolley for the ride to the boat dock, down a slope shaded with tall oaks. When he was growing up, he said, just about everyone fished from small one- and two-person flat-bottomed cypress boats. “And after fishing,” he recalled, “we’d sink them in the shallows before we left. That’s how we preserved them.” The steep hill between the river and the clubhouse was once chockablock with cypress boats. These days, Stewart doesn’t think there’s a single one left on the river.

Photo: Tim Romano

Casting in tight quarters.

We motored upstream in Stewart’s skiff to a place called Knox Suck. A “suck” is what locals call the river braids, the place where the river splits and divides into a dendritic watercourse. In a narrow suck, the river is smaller and more intimate. Stewart will fish the Satilla year-round, but for a solid month he’ll follow the falling water of spring, fishing most days of each week as the river drains out of the surrounding swamps and cypress sloughs. “The joke around here,” he said, “is that you know it’s going to be a good redbreast year when the fish are eating acorns.” In the suck it’s easy to fire a cast from bank to bank, and we fished the eddy lines and deep, slow pools, pulling out redbreasts of every imaginable size. Stewart sorted them out in his South Georgia argot: “That’s a butter bean,” he explained of a fish that wouldn’t cover half my hand. The next size up was a “potato chip.” A big hen redbreast was a “Sally.” Larger still was a “slab.” When I hauled in a decent-sized spawning male, Stewart wolf whistled. “The redbreast is the prettiest fish in the river,” he announced. “A rooster’ll look right down his nose at a catfish.”

Stewart is a man of some means. He fishes offshore blue water. He hunts big whitetails in Kansas. But by any measure, he seemed as happy as a man could be sitting in a canoe with a fussy motor, casting to a fish that might seem prosaic and commonplace.

There are two reasons for that, he told me. “First,” he said, laughing, “it helps that these little fish get along right well with a skillet.” But mostly, redbreast sunfish are homegrown trophies. They are just down the road, Stewart said. Within an afternoon’s reach. “This is our game,” he said, “and we get to play it in a place so wild and pretty that you just can’t hardly believe that hardly no one knows it’s even here.”

That sense of gratitude—of feeling fortunate and blessed to have been raised on a redbelly river—was evident with nearly every person I spoke with in South Georgia. One morning I fished the Satilla with Chuck Sims, a second-generation undertaker from Ambrose County. In 1934, Sims’s grandfather helped establish one of the river’s venerable fishing institutions, the Coffee County Club. The main clubhouse was called the “lean-to,” so named when the structure fell off a flatbed trailer and was simply left in place. “No woman alive would go in there,” Sims said. “And that was kind of the point.” The Coffee County Club has cleaned itself up a bit these days. Lots of younger people have moved mobile homes and small cottages to the communal landing. In the spring and summer, the river is thronged with anglers. For years, Sims ran an old Evinrude motor folks on the river called the “Skeeter Smoker.” “Folks would holler out at me,” he said, laughing, “Sims, get on over here! The yellow flies are about to eat us up!”

Photo: Tim Romano

Rocking chairs at the Coffee County Club.

His current motor seemed to be from the same mold. It’s an old twenty-five-horsepower Johnson that Sims rides hard. He grinds into sandbars and bumps over logs, bellowing to his guests and his craft like they are children playing in the front yard.

“You boys hold on!”

“Hang loose! I don’t want to shear a pin!”

“Uh-oh. We’re stuck.”

Sims is an institution on the Satilla, but smoking motors aren’t all he’s known for. He spent eighteen years in the Georgia state legislature, from 1997 to 2015, and he’s well remembered not only for his homespun delivery but for his passionate defense of the Satilla and other Georgia rivers. In 2010 he led an epic effort to ban all motorized vehicles—ATVs were the primary target—from riding river bottoms during low water. The machines decimated redbreast spawning habitat. “Getting that passed,” he said, “was the start of a lot of good conservation work on these rivers.”

Photo: Tim Romano

Lily, a Boykin spaniel, watches the action on the river.

At one point we tied up to a downed tree for what Sims called “young’un fishing”—long poles, a bobber, and a hook. The river was low, and clear enough to make out old elliptical depressions in the sandbar bottoms where redbreasts had built their spawning beds. “I’ve got a bird dog that’ll point a redbreast bed,” Sims said. “You can see her up there on the front of the boat, smelling those beds, and she knows it’s something, she just don’t know what it is.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“But I do,” he said.

Photo: Tim Romano

The view from the bow on an early morning.

The next afternoon I met two sisters whose family is nearly synonymous with Satilla River redbreast fishing. Shannon Bennett and Sherry Bowen were two of the three Strickland girls—their youngest sister, Stacia Fuller, completed the trio—who were fixtures on the Satilla in their growing-up years. Their grandparents ran the old Strickland’s Fish Camp, which had its own boat ramp, a few simple cabins, and a café where the cooks would fry your catch. Their father, A. J. Strickland, was a longtime Pierce County commissioner and champion of river conservation. “You’d never know who he was going to have in the boat with him,” Bennett recalled, “from the poorest to the wealthiest. Even the governor one time. If somebody wanted to go fishing, that’s all he cared about. Showing them his river.”

We were at the old Strickland river landing, under giant oak trees where the sisters had played on rope swings, watching a family fish from the sandy spit where all the Strickland girls were baptized. It’s here that local farm workers would bathe after priming tobacco, scrubbing with river sand and Ivory soap, and where local kids came to swim and play.

Photo: Tim Romano

A young angler with her catch at the Atkinson landing.

“I’ll tell you what this river did for us,” Bowen said. “We have turkey hunted on the banks, we have fished, we have hog hunted, and we did it all with whatever community was right here. Family, rich people, poor people, friends black and white, it didn’t matter. It was like this river was a bridge for all the people growing up around here.”

And redbreast sunfish provided a sort of elemental repast, a communion meal that washed away class and standing, lineage and pedigree.

“When people would pass,” Bennett said, “instead of bringing fried chicken or a casserole, Daddy would catch a mess of redbellies and show up at their door.” She paused for a moment to watch a young girl fight a fish that pulled at her fishing rod in deep, pulsing tugs. “Years and years later,” she said, “people would still tell us about Daddy bringing them fish and how much that ministered to their grief.”

Such sentiments—that a pan-sized river fish could help transcend class and privilege, galvanize efforts to conserve, and function as a salve to the soul—helped fuel the last few days of my Satilla journey. Like everyone I spoke with, I took to the water. For three days photographer Tim Romano and I paddled the river, fishing its sloughs and sucks and camping on sandbars with Gordon Rogers, who worked as the Satilla Riverkeeper before he moved west to the Flint River.

On the second morning on the river, I draped my sleeping bag over a sunny willow tree and tried to talk myself into building a fire for eggs and sausage. The night before, we’d fried fish and cooked a smoke-infused ratatouille over a driftwood blaze, and a pile of leftover firewood beckoned. But the river unspooled along a low bar of sugar-white sand, a curve of clean beach and big woods, and I could hear fish feeding on the far bank. I saw one significant slurp, active and vigorous enough to leave paisleys of bubbles trailing in its wake. I watched as my stomach grumbled. A second slurpy take sealed the deal. I walked to the canoe, tipped out half my coffee, and pushed the boat in the water.

Photo: Tim Romano

The author whips up a dinner of fresh fish and veggies on a Satilla River sandbar.

I arrowed the canoe across the current, ferrying upstream from the campsite. On the far side of the river the bank was a five-foot-tall vertical face of knotted roots and exposed white sand cliff, the water stitched with fallen and leaning trees that slowed and eddied and pooled the river in a crazy quilt of microcurrents. I slipped the canoe tight against the blowdowns, turned the bow downstream, and sculled the paddle with my left hand as I cast Dickie Winge’s buggin’ pole with my right.

It was a Tolkienesque world of deep shade, overhanging brush that scraped my shoulders, drooping branches, and dripping moss. I lifted the little popping bug, snapped it behind me, and dropped it into a swirl of melted caramel that unspooled into a calm slick behind a log.

I remembered Winge’s admonition to let the bug’s ripples flatten and fade before twitching the lure. I recalled Jimmy Stewart’s description of an old friend in an old wooden boat, gliding down the river in a fog so thick that it seemed like the man floated like a ghost over the water. And I thought of Chuck Sims with his dog on point in the bow of the boat, the musk of a redbreast spawning bed in his nostrils, the two of them staring intently into the copper water, one wondering what the smell could be and the other knowing that it was the scent of so many things that matter.

This article appears in the August/September 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.