Travel

Frances Mayes Finds Joy in Going Home—Whether to North Carolina or Tuscany

The Georgia-born writer muses about Italy, travel, and what life might have been like had she stayed solely under the Southern sun. Plus: Mayes’s three Italian small-town picks

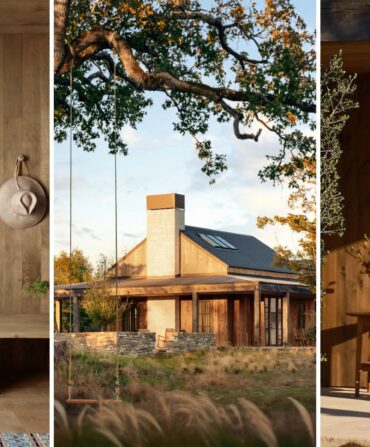

Photo: Infraordinario Studio

Coming and going, packing and unpacking. Where’s the green sweater? Oh, in Italy. Don’t we have a wok? Yes, in North Carolina. They’ve canceled the flight. We’re missing Tori’s birthday. We missed Carnevale. Really, the windows need washing. I forgot to plant the bulbs before we left. Who will house-sit the cats? Water is leaking out of the fridge? Yes, the cousins are coming to stay for two weeks.

We live in two countries. When we’re in one house, the other sends subliminal messages: Come back. Surely one home in the place you love most is best, with vacations in other magnetic locations. Is that true? But where is the place you love best? Loving two countries is like being a bigamist. Where shall I sleep tonight?

No one remotely sympathizes with the push–pull of living in two places. Why should they? The luck of having a house in Italy!

But it wasn’t luck that enabled me to buy an abandoned villa on a hillside in Tuscany. It was risk. With my divorce settlement, I bought my own place in San Francisco, where I taught poetry at the state university. The bonus was long, free summers. When I rented a house in the Tuscan countryside with writer friends (one was Ed, now my husband), I fell hard for the landscape and way of life and couldn’t wait to return.

After a few summers of hiking Roman roads, dinners under olive trees, and a thousand Renaissance Madonnas, I craved to have Italy as part of my life. Risk averse, I nevertheless became determined to find a way. Real estate prices were going up, up in California. I had the bold idea of taking equity out of my house and plunking it down on Bramasole, a run-down villa the color of sunsets, perched under an Etruscan city wall above a valley where Hannibal defeated the Romans in 217 BC. It would work out. I might write freely there, and Ed and I would share a romantic and fascinating life. (This was long before every other villa became an inn or a cooking school. No one did this.)

Photo: Marco Sallese Fotografia; Infraordinario Studio

The Bramasole living room’s raised fireplace; Mayes harvests lavender.

Those fantasies happened. All who told me I was insane constantly visit. Even my financial adviser came! I wrote many books in my third-floor study overlooking Hannibal’s valley. My daughter has been to Italy every year. My grandson grew up with Italy as a natural part of his life. Ed’s sisters and mine, many friends, all formed their own bonds. Amazingly, readers from Poland, Estonia, China, and elsewhere walk by, often leaving mementos and notes in the shrine below our house. Two Americans asked to scatter the ashes of their spouses on our land. Ed, a poet, became an olive farmer. Our Bramasole olive oil now goes to people in Qatar, Brazil, Canada. I like to think our melted-emerald oil is spreading joy in kitchens all over the world.

It’s easy to see the appeal of spending time in Italy. But why stay? Decades have flown by. I’m still there. “Should we have stayed at home?”—sometimes I pick up Elizabeth Bishop’s poem because the question is a good one. She lists a string of things that “…surely it would have been a pity” not to have heard, seen, pondered—the trees along a certain road, the clack of wooden clogs, a bamboo church, even the rain in another country. Lightly, she answers her own question. No!

I can make my own list of what would have been a pity not to see:

Tender green bud break in the vineyards on the way to Montepulciano

A lone punter on the Arno seen from the Santa Trinita bridge at dawn

The fresco of the local landscape we uncovered in our dining room

Ed’s Italian driver’s license—the test is notoriously hard

Rows of agretti, the crunchy spring vegetable, springing up in the garden

The piazza on summer nights, the gelato stroll, the late glass with friends

Weddings—endless, elaborate—that rival the royals’ and last eight hours

Tiny white olive flowers the first day they turn into olives

Harvest! The lasagna picnics, golden nets spread with black and green olives

Tasting parties just after pressing—everyone thinks theirs is best

My lavender walk swirling with yellow, blue, white butterflies

Fragrant lemon trees, shiny orbs fogging the glass of their winter room

Morning in the piazza after a long absence, coffee whooshing, bright faces

By not staying at home, I missed out on a profoundly different sort of life.

I was raised with a palpable sense of place. My Fitzgerald, Georgia, was a deep-rooted one-square-mile world. I was familiar with every street and every building. Everyone knew my family, and we knew everyone. Devouring the great Southern writers—Welty, O’Connor, Agee, Wolfe, Aiken, Faulkner—underscored my innate sense of the power of the landscape. But I was also reading Hemingway, Woolf, Dostoyevsky, Freud, Proust, making my way around the library. I was sixteen when I realized the eggshell must crack. Fledgling, I wanted to fly.

Years on, long after I began my Italian life, I moved from California back to the South because I had never really left. (In California, I was always the surprised and fascinated visitor.) Six months in the South, six in Tuscany. I found it suited my desire to be extant in more than one version.

My chosen small town in North Carolina, I discovered, shared similarities with my hometown. Revised for the better, updated attitudes and laws, but it exuded the same intense sense of community. As we looked for a house, the agent told us not only about each owner but about what their daddy did and where their mama bought her roses and what a shame the boy didn’t get into UNC. Ed (from Minnesota) rolled his eyes to hear what sorority or fraternity they belonged to. What does that possibly have to do with the paltry kitchen?

Photo: Marco Sallese Fotografia; Infraordinario Studio

An antique corner cupboard for vintage glassware and plates in the dining room; layers of whitewash previously covered this fresco.

“This is the sort of place where your neighbor knows what you’re going to do before you do,” I explained. I felt right at home. New friends seemed like lifelong friends. With all my moving about, my sense of time often blurs. Back in a small Southern town, I noticed that many people had a much sharper sense of chronology about their lives than I did. Friends go all the way back to kindergarten. They remember the year someone married, the winter of the big snow, the date of an aunt’s death, the summer the Eno River flooded. Whose granddaddy was president of the bank and whose was a yellow dog Democrat and who was sweetheart of Phi Delta Theta. “Oh, my sister was Phi Delt sweetheart at Georgia,” I said. Ed, again the eye roll. Many kitchen doorways were marked with the heights of those who grew into adults there. Living forever in place, one sees not only the neighbor or friend but the entire palimpsest of that person. In contrast, when it comes to my many friends in Italy, I often don’t know of their first marriage, or what they majored in, or even why they’re not in touch with their brothers. We lack the benefits of a shared history. Much is lost by not sticking to your roots.

“Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? / Where should we be today?” Bishop asks. Wandering the road not taken, what books would have been written? But in my now-restored villa, it’s not complicated. My American life is a given. I know what the day will bring. Italy offers the constant element of surprise. I cannot predict the day. We will never exhaust the joys of travel, from the south of Sardinia to the north of Alto Adige. The marvel of the gardens, the basket of ripe tomatoes, the cypress lane, the of-this-time friends from all over the world, the satisfying this is what I came for, this is who I am—all feels right. Where you feel at home chooses you.

“Oh, must we dream our dreams / and have them, too?” Bishop wonders. Yes, my friend. Well said.

Plus: Italy Off the Beaten Path

Frances Mayes’s small-town picks

Ponza

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Grand Hotel Santa Domitilla (@grandhotelsantadomitilla)

Catch the ferry at Terracina in Lazio, and soon you’re on an enchanting island with a picturesque village stacked along the Tyrrhenian coast. Blue, red, yellow, and white boats bob in the harbor, and you can hire one to take you to hidden coves. Or ride a Vespa into the hills covered with wildflowers and find your own hidden beaches. The vibe is relaxed, even retro. Lively seafood restaurants, cobbled lanes, tumbling bougainvillea and jasmine—this is the island paradiso one dreams of. At the Grand Hotel Santa Domitilla, you swim in grottoes, one cool, one warm. Odysseus is said to have spent a year on the island. Easy to see why.

Sansepolcro

This handsome market town in the valley of the Tiber is home to “the greatest picture in the world,” according to Aldous Huxley. Piero della Francesca, native son, left the stunning Resurrection, along with Madonna della Misericordia and the haunting fresco fragment St. Julian. Unlike other Tuscan towns, Sansepolcro is flat and easy to explore. Si mangia bene, one eats well here. Trattorias serve forth authentic Tuscan fare—the best roast pork, big steaks, tagliolini with truffles, and delicate ravioli in sage and butter. Stay at Relais Palazzo di Luglio, then travel to nearby Monterchi, a jewel-box village where you’ll find yet another lovely Francesca fresco.

Marzamemi

The huge Piazza Regina Margherita is ringed by trattorias, low white buildings that recall the Arab heritage, and a church to anchor it. Almost everyone paints their door celestial blue. The town was once a prosperous tonnara (tuna harvesting and processing) center. I learned about the village when I told an acquaintance that we were going to the baroque towns of Sicily—Noto, Ragusa, Modica. “Oh,” he said, “we all go to Marzamemi.” Who’s we? I felt subtly put in place but nevertheless followed his lead. Through the Thinking Traveller company, we rented a house with friends in the nearby Vendicari Reserve, with its beautiful beaches. Try the anchovy pasta and the grilled or raw tuna at one of the seafood restaurants. There’s live music at night and dancing in the moonlight! Walk around the little shops. Dip into the Ionian Sea. Perch on a seawall with a beer. Then go visit the great baroque towns.