Conservation

Peacocks in a Kaleidoscope of Color

Steel, midnight, peach, hazel, platinum, taupe, jade—driven by the thrill of creation and discovery, the Missouri farmer Brad Legg has almost single-handedly spurred the proliferation of crazy-colored peacocks

Photo: Sam Raetz

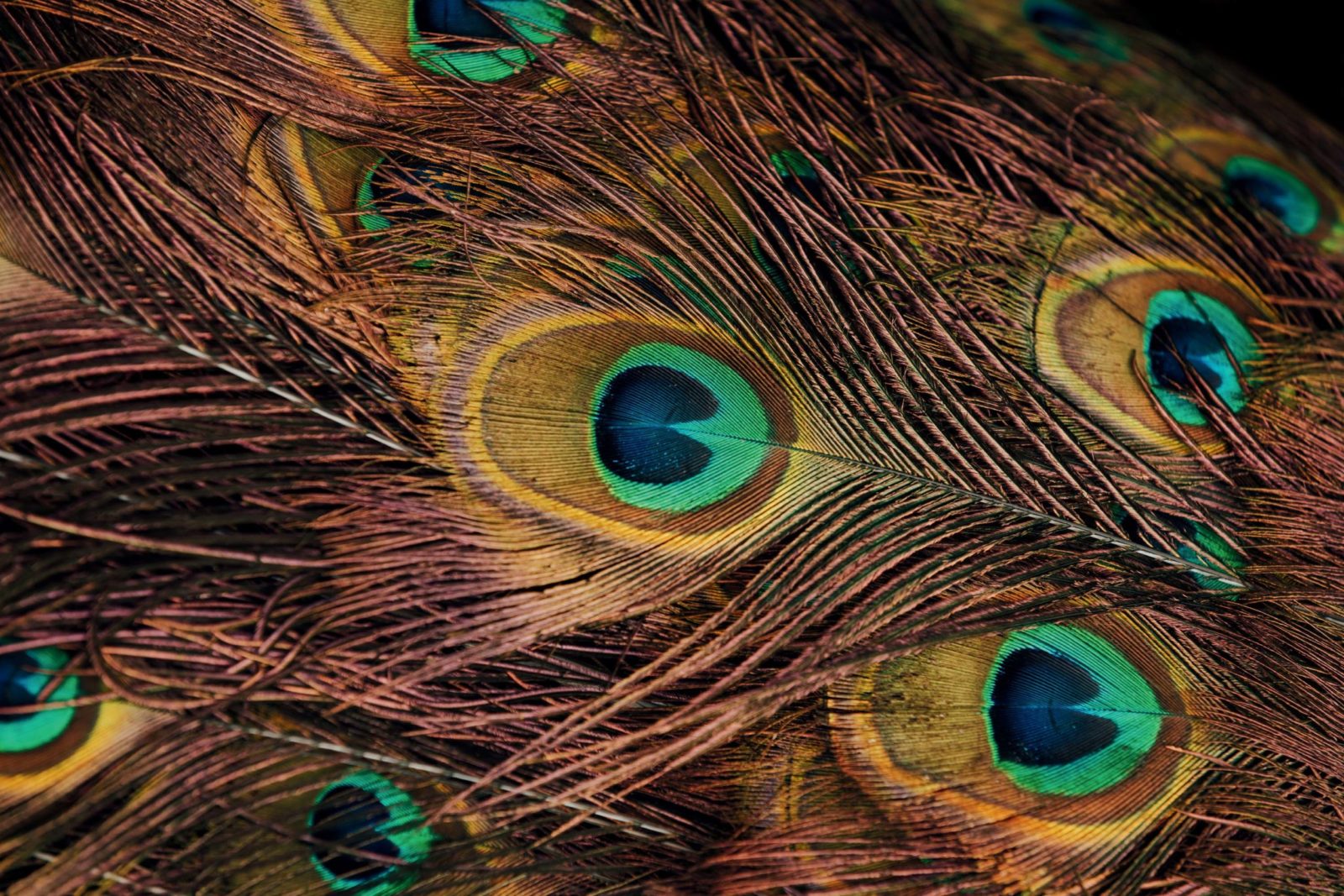

India blue The train of the most common peafowl species.

Brad Legg was packing up his peacocks at the end of an animal auction in Nebraska when a boy approached him with a polite question.

“Mr. Legg,” he said, “I’ve got a peacock, and I don’t know what it is. If I told you the colors, could you tell me?”

Legg was the obvious person to ask about a strange peacock even back then, in the autumn of 1998. The regulars at the auctions in Tennessee and Ohio and Kansas, anywhere within driving distance of Legg’s Missouri farm, were used to seeing him pull in with a trailer full of peafowl—black shoulders and whites, Spaldings and cameos and plain old India blues. In the peafowl world—peafowl being the collective noun for peacocks, peahens, and peachicks—Legg was a celebrity: A few years earlier, one of his birds had appeared on the cover of The Peacock Journal (“a national peafowl and alternative livestock publication”). It was a silver pied, believed to have been the first of its kind hatched in North America.

“Sure I could,” Legg said to the boy. “What’s it look like?”

Green neck, the boy told him, cinnamon body, pastel train, kind of pale.

Probably misidentifying a purple peacock, Legg thought. Maybe a cameo. But the boy said no, he’d seen pictures of both, and his bird wasn’t either. The boy’s father happened along. He confirmed the description and said he’d never seen anything like it.

Legg’s pulse quickened. “Do you have any pictures?”

“No, sir.”

Legg’s son Brandon looked up at him. He was ten years old. “Dad,” he whispered, “we gotta go see it.”

It was six o’clock on a Sunday night. The drive home took five hours; Brandon and his sister had school in the morning; their mom, Patsy, had to go to work; and Legg had to be at the Fuji plant, his real job, making sure a few thousand rolls of film were properly processed. And he was still packing up the birds, more than a dozen, that he hadn’t sold because the bids came in too low.

Legg looked at the boy’s father. “How far away do you live?”

They drove ninety minutes northwest, away from Missouri and into the sandhills, then another twenty on back roads and dirt until they came to a spread with an old dairy barn and, in front of it, a pen of rough timber and wire. The father disappeared inside.

“He walks this bird out,” Legg says now, more than twenty years later, “and I’m standing there fricking dumbfounded.”

“Your mouth just drops,” Brandon says.

“It was a new color. It was a jade,” Legg says. He pauses, eyes wide. “I just…I get goose bumps just telling this story again.”

Photo: Sam Raetz

The India blue spalding, a cross between two species, an India blue and a green peafowl, photographed on Legg’s Peafowl Farm in Kansas City, Missouri.

I first met Brad Legg in the fall of 2018, until which time I believed I knew exactly what a peacock looked like. Gangly bird, about the size of a small turkey, with an enormous train fanning out into an arc that, because the feathers are iridescent, shimmers with turquoise and azure and emerald and copper and magenta. A Seussian crest sprouts from the head, like a bouquet of Whoville flowers, and the breast and neck are an unreal cobalt, the color of fairy-tale lakes. I knew there was the odd white one, but by and large peacocks were gleaming blue birds with big, beautiful feathers.

This was a failure of my imagination.

Photo: Sam Raetz

Brad Legg, who began raising peafowl at age ten, with a steel variety.

I was in Missouri for the twenty-fifth annual convention of the United Peafowl Association—a totally real thing to which I have paid membership dues. A year earlier, I’d bought two peacocks and a peahen. They were surprisingly cheap, $125 for the trio, and I’d grown quite fond of them, but they were not a well-considered purchase. Two boys and a girl, in fact, proved an untenable imbalance of avian hormones, so I’d already had to add another hen. I’d turned to the UPA for help, and a full-on peafowl convention was, like peacocks themselves, one of those things I’d never considered until the opportunity presented itself.

The UPA convened that year at the Four Points near the Kansas City airport because the hotel is less than fifteen miles from Legg’s Peafowl Farm. “It’s like Disneyland!” one of my fellow conventioneers squealed when Legg’s pens came into view, 150 low sheds of lumber and sheet metal with long, wired runs set out in rows and filled with birds.

Very few of those birds, relatively speaking, were blue. Or bright.

Legg’s is not the largest peafowl operation around: During the summer hatching season, an average of three thousand peacocks, peahens, and peachicks fill the property, a respectable but not overwhelming number. Yet Legg has bred them in 189 varieties, far more than anyone else in the country and, quite possibly, on the planet. And that number is out of date. In 2018, when the UPA had already recognized 225 varieties bred in ten colors and five patterns, the organization also approved seven new colors Legg presented—two of which he had found and one he had actually conjured—and one new pattern. Since each color can be bred in ten different varieties from patterns and combinations of patterns—a jade (color) black-shoulder pied white-eyed (three patterns), for example—and each mutant of the common India blue species can be crossed with a green peafowl to make a hybrid called a Spalding, that constituted 140 potential new varieties right there. At least five more (not yet officially recognized) colors have been found or created since, and Legg is developing more.

Photo: Sam Raetz

A jade peafowl, a variety Brad Legg found by happenstance in Nebraska.

At the time, I was unclear as to why, or even how, one might improve upon the original peacock. It is a bird of myth and legend—guarding the gates of paradise, consorting with the goddess queen Hera, embroidered on Elvis’s favorite Vegas-era jumpsuit—for a reason: A peacock is an ethereally beautiful bird. That it is an illogical bird, a forest dweller weighted with an ungainly carpet of sparkly feathers trailing from a shamelessly brilliant body, only adds to its wonder. It is a bird not just of myth but possibly of magic, having not been eaten into extinction by jaguars.

And yet people tinker. So very human of us. If a bird is beautiful, someone will believe it can be made more beautiful, or at least different, which is its own kind of beauty. Someone like Brad Legg.

“I like having something no one else has,” Legg told me one afternoon on his farm among the endless rows of pens. A sturdy man of sixty-one, with white hair and rough hands, he doesn’t look like a fancier of birds, let alone fancy ones. “And if I have that something, I want to make it in the hardest variety of every kind.”

One of the hardest varieties to create, for the record, is a male purple black-shoulder silver pied. It took Legg twelve years to hatch one, and it is, he says, “the most beautiful bird we ever raised.”

Photo: Sam Raetz

The train feathers of a midnight variety.

To be clear, the Leggs and other breeders are working with new varieties of peafowl, not species, of which only three exist: green peafowl, which are endangered in the wild and relatively delicate; Congo peafowl, which are smaller and rarely seen outside of a handful of zoos; and the hardy, ubiquitous India blue, native to the subcontinent but long since spread across the planet, like starlings and zebra mussels.

In simple terms, Legg and others are isolating India blues with rare genetic mutations that affect their color or pattern and breeding them in very targeted ways—this cock with that hen, the resulting chicks with this hen and that cock—until they establish a line that breeds true and healthy. That is, in other words, until a jade hen and a jade cock reliably produce jade chicks. Most of those mutations occur naturally, and seem to be mainly aesthetic, not significantly different from the way a human gene will produce red hair or blue eyes. Others get created in the pen. Legg eventually developed taupe peafowl, for instance, from an initial mating of a purple hen and a regular-looking India blue cock, and peach began with a cameo cock and a purple hen.

Photo: Sam Raetz

From left: A Spalding; an opal pied; an India blue pied, one of the first established mutations.

This is all quite modern. The first three India blue mutations—white; pied, where the bird is splotched with white; and black shoulder, in which the wings have deep blue-black feathers instead of striated brown and beige ones—were all known by the 1800s. Yet the next recognized mutant didn’t show up until 1967, a brownish bird hatched in Maine and initially called a silver dun before the name was changed to cameo.

Brad Legg hatched his first peachicks a few years later. He grew up on a cattle farm, watching his father tinker with his own hybrids. Brad was the youngest of four, and when he was very small, four or five, his parents would play cards with their nearest neighbor, who had a peacock. “I’d sit out there and watch this bird for two or three hours while they played cards,” Legg says. “I don’t remember this, but my mother said I told her, ‘I’m gonna have peacocks when I get older.’”

Photo: Sam Raetz

The mantle of an India blue pied.

When he was ten, Legg bought around a dozen peafowl eggs through a family friend for a dollar apiece, borrowed an incubator, and hatched his first flock. This was unusual in Missouri, raising peafowl, but not so much as it would have been in, say, Brooklyn. Legg was a farm boy, after all. He and his brother took turns picking first which calf to raise for 4-H, and he reared Suffolk sheep and Checkered Giant rabbits and Cochin chickens. “I won everything I showed in,” he says. “Got to where they hated to see the Leggs coming.”

(He did not show peacocks, however, because there are no peacock shows. It is the damnedest irony: There are rabbit shows and chicken shows and cattle shows and Miss Universe pageants, yet a bird known specifically for its beauty, a creature with no useful purpose other than to be ogled, has no formal arena in which its appearance can be judged. The reason is that the peacocks would have to be taken to such shows in very large cages, “and they’re not gentle in strange places,” Legg says. “They fly up and break their necks.”)

By age sixteen, Legg had whites and black shoulders among his two dozen or so India blues. Four years later, he’d added the truly exotic varieties: pied peacocks he bought as chicks from an Oklahoma man whose pied cock purportedly was the first in the United States, having come from a zoo in Mexico City; and ten cameo chicks he’d bought before they’d even hatched. He paid $100 for each—roughly $330 in today’s money—a crazy price for chicks, but they were different.

Photo: Sam Raetz

A charcoal black-shoulder variety.

Legg managed a cattle farm at that time, but he sold a few birds on the side. The peafowl market always proved a healthy niche, especially for the more exotic birds. In the mid-eighties, for instance, he had a surplus of whites, so he spent $7.34 for a two-line classified in the Kansas City Star. “First thing in the morning, that phone started ringing and people started coming,” he says. “They were fighting to get to the farm first.” He can’t recall exactly what kind of person raced to buy a white peacock in the eighties, except for the guy in a white Cadillac who owned a nursery and said the birds put people in a spending mood. But he does remember he made $1,100 that Sunday.

Meanwhile, the eighties began a burst of new mutants. The white-eyed pattern—named for the color of the iconic eyespots on the peacock’s train—stabilized in California. Purple and charcoal popped up in Arizona, and in Tennessee a man named Buford Abbott, shortly before he died, found a dark metallic-colored bird now known as Buford Bronze. Both peach and opal took hold in the early 1990s.

In 1992, Legg attended a small-animal sale in Kansas. The lots up for auction included a little shoebox containing a tiny white chick with two tan spots on its neck. “It was just the weirdest-looking peachick that’d ever been seen, ever,” Legg says. “I didn’t know what it was, but it was going home with me.”

Legg couldn’t stay, so he asked his friend to buy it for him when it came up for bid.

“Okay. What’s your limit?”

“I don’t have a limit,” Legg said. “You’re not listening to me: Buy the bird.”

That weird peachick cost Legg $210. A year later, two more of those peculiar birds showed up in different flocks around the country. All three could be traced back to those white-eyed birds developed in California, a genetic stew of white, white-eyed, and pied India blues that became known as silver pied. Legg’s silver pied appeared on the cover of The Peacock Journal.

“When that magazine hit publication,” Legg says, “in forty-eight hours we had phone calls from twenty-six states wanting to buy it.” The appearance of this bizarre peacock, like a white bird flecked with glitter paint, sparked new growth in the market. “And the next one that sent it over the top,” Legg says, “was midnight.”

Midnight was another happenstance find, an odd bird in a box at an auction in Kansas. Legg had intended to skip that sale, too, and only went because Brandon, who was ten at the time, wanted to go. “That was game day for me,” Brandon says. “I didn’t do sports. Soccer was on Saturday and the sales were on Saturday, and I had to pick one. I went with the animals. It gets in your blood.”

Photo: Sam Raetz

An India blue.

Legg bought the midnight bird, a blackish cock, for $32.50 in the autumn of 1998. A few weeks later, he and Brandon found themselves gawping at that jade bird in Nebraska. The farmer didn’t want to sell, though: His boy had bid on the birds Legg had decided not to sell at the auction, and he’d happily trade that jade cock, and two matching hens, for a pair of Legg’s birds.

Legg gave the boy every peafowl he had left, fourteen if memory serves. He still thinks he got the better end of the deal.

Photo: Sam Raetz

The ocelli of a jade’s train feathers.; an indigo, one of the new colors the United Peafowl Association approved in 2018.

Legg’s Peafowl Farm accommodates 150 breeding pens, where specific peacocks are housed with specific peahens to produce a specific variety of chick. Beyond breeding the more established varieties and getting reliable genetic results—a black-shoulder cock and a black-shoulder hen, for instance, will produce black-shoulder chicks—everything gets progressively more complicated, depending on the color, the patterns, and the combinations. Some of the colors, like purple and cameo, are sex-linked recessive, which means the male carries them without necessarily showing the characteristics. Silver pieds require that jumble of three different mutations. Breed a black shoulder with a plain India blue and none of the chicks will look like black shoulders but all of them will carry the black-shoulder gene. So if you want a male purple black-shoulder silver pied? Of course, it took Legg twelve years to produce it.

Photo: Sam Raetz

A peach variety, a hybrid established in the early 1990s with a cross between a cameo cock and a purple hen.

“That’s a charcoal black-shoulder silver pied,” he tells me during a later visit, pointing at a white male splotched with dark gray. “I can make that same bird in a Spalding, and I can do it”—he wheels, points to another pen—“right there.” (It’s more complicated than that, requiring several, perhaps many, generations. But the process would start in that pen.) A Spalding is a hybrid developed in the 1930s by a bird fancier named Eudora Spalding, who wanted to inject the cold hardiness of the India blue into the more elegant frame of the warm-weather greens. At this point, there’s a Spalding version of just about every variety.

Legg has operated his peafowl farm full-time since 2001, when he went part-time at the Fuji plant (he left for good in 2006, when digital cameras killed the film industry). The growth has been exponential, and he measures it by the generations. When he was twenty, Legg had five kinds of peafowl. When Brandon turned twenty, in 2008, there were eighty-seven varieties on the farm. A decade later, when his son Dallas turned twenty—there was a ten-year gap between the second and third of the Leggs’ four kids—the family was raising about two hundred types of peacocks and peahens.

Photo: Sam Raetz

An ocellus, or eyespot, of an India blue feather.

It’s meticulous work, keeping track of all those chicks in all those varieties. They write on each egg the number of the pen where it was laid, and as a rule, that’s done before leaving the pen to avoid confusion. They place the egg under a Cochin bantam for at least two weeks (so the peahens can continue laying), and then they shine a light through the shell to see if a bird is developing. The fertile ones go into an incubator for another couple of weeks until they’re moved to a hatcher, each pen’s eggs grouped in a separate compartment so the midnight pieds don’t get mixed up with the cameo black shoulders. That happens on a Saturday so the chicks all hatch at roughly the same time. On Tuesday, they mail out chicks to customers who have prepaid for an eight-pack of the more common varieties, eight being enough to generate sufficient body heat. The rest get tagged with a numbered clip in each wing.

The Leggs have clipped more than twenty-seven thousand chicks over the years, and sold tens of thousands of day-old chicks, give or take. They can’t breed enough to keep up. “The peafowl market’s been going up for twenty years,” Legg tells me as he stops his golf cart in front of a pen. “There hasn’t been a down year yet. Everything’s hot now.” His birds aren’t cheap. Aside from the $200 India blue male, the least expensive one on his list, a white cock, costs $350, and a pair of India blue yearlings go for $450. Prices rise significantly with the degree of breeding difficulty.

Photo: Sam Raetz

An India blue silver pied.

I nod toward the charcoal black-shoulder silver pied. “How much for him?” Legg is quiet for a moment. He’s pretty positive it’s one of the only male charcoal black-shoulder silver pieds in existence. And it took him twenty years to make.

“Oh, I guess—” he starts, then pauses. “Well, I wouldn’t even know how to price it.”

Photo: Sam Raetz

In the winter, the males Legg will take to market in spring—including, here, an India blue, a black shoulder, a silver pied, a Spalding, and a white variety—roost in the barn to keep their trains in good condition.

That first time I visited Legg’s Peafowl Farm, with the UPA, Daniel Potente was there, too. He’s the president of the association, and birds are in his blood. His father had birds and his father had birds and so on, back at least four generations, probably more. It had rained all week, and we were standing in mud in front of a pen of Montana peafowl, one of the new colors approved that year, along with ivory, platinum, steel, indigo, hazel, and mocha.

“Not a lot of blue here, Danny,” I said.

“Yeah, but that’s a beautiful bird,” he replied.

“It is,” I agreed. “It just doesn’t look like a peacock.”

A Montana bird is beige. Legg got a call about it in 2013, from a woman in Montana who was trying to figure out what these strange-hued birds were. He started swerving off the road, he got so excited, and when he called Brandon to tell him, Brandon asked, “Why aren’t you driving to Montana already?” (“When we get a call, we go,” Brandon told me later. He and his father have visited forty-two states looking at odd birds.)

Photo: Sam Raetz

A midnight, a variety Legg first discovered at a Kansas auction.

Brandon ended up driving the almost 1,900 miles to Montana with his wife, toddler daughter, two-month-old baby, and, in the back, nine peafowl to trade with the woman. It took him the better part of a day, and he busted three nets, but eventually he caught two beige males, a beige chick, some hens and another cock that might have been the parents, and six eggs that he nestled in a heating pad for the long drive home.

That’s the curious thing about the exotic new varieties. A few—taupe, ivory, and peach, for example—were created. But the found ones have mostly been castoffs, birds other people didn’t want. The farmer with the jades would have happily traded for a single pair of brighter birds. The man who sold the midnight asked Legg why he was so interested in a mutant, and Legg told him it was because his neck wasn’t blue. “Well, hell,” the guy said, “that’s why I’m selling him. He’s supposed to have a blue neck.”

I understood what he meant. “A lot of these colors,” I said to Potente, “aren’t, you know, colors.”

“Get outta here. Of course they’re colors. Did you see the platinum? Steel?” (Legg found the steel at a swap meet in 2011. Thought it was a midnight until Dallas finally put their trains side by side.)

“I did. Not peacock colors.”

He raised an eyebrow at me.

“A Montana peacock,” I said, “is never going to be written into a fairy tale.”

The Leggs get that. “Honestly, it’s just an eye-appeal thing,” Brandon says. “It’s no different than how some people like spotted horses and some people like solid horses, and some people like spotted dogs and some people like solid dogs. Same thing.”

And beauty isn’t always physical, tangible. The act of creation can be as beautiful as—often more beautiful than—the creation itself. A charcoal black-shoulder silver pied is not, to my eye, a particularly attractive bird. But the fact that it exists, that possibly only one exists, is breathtaking.

There will be more, too. Legg and his children are still combining this bird with that one. Brandon keeps about four hundred birds, and if the Leggs come across something rare, they put half at his place, dividing the stock in case a storm blows through or a pen catches fire. “If there’s something I tried to make and haven’t,” Legg says, “it’s only because it hasn’t happened yet.”

And they’re still looking, always looking. “They’re out there,” Brandon says. “Mutants, new colors, they’re out there, all across America today. They’re just waiting to be found.”

Photo: Sam Raetz

A Montana struts its stuff; Legg found the beige variety in its namesake state in 2013, and the UPA also approved it as a new peafowl color in 2018.