Arts & Culture

Indelible Talent

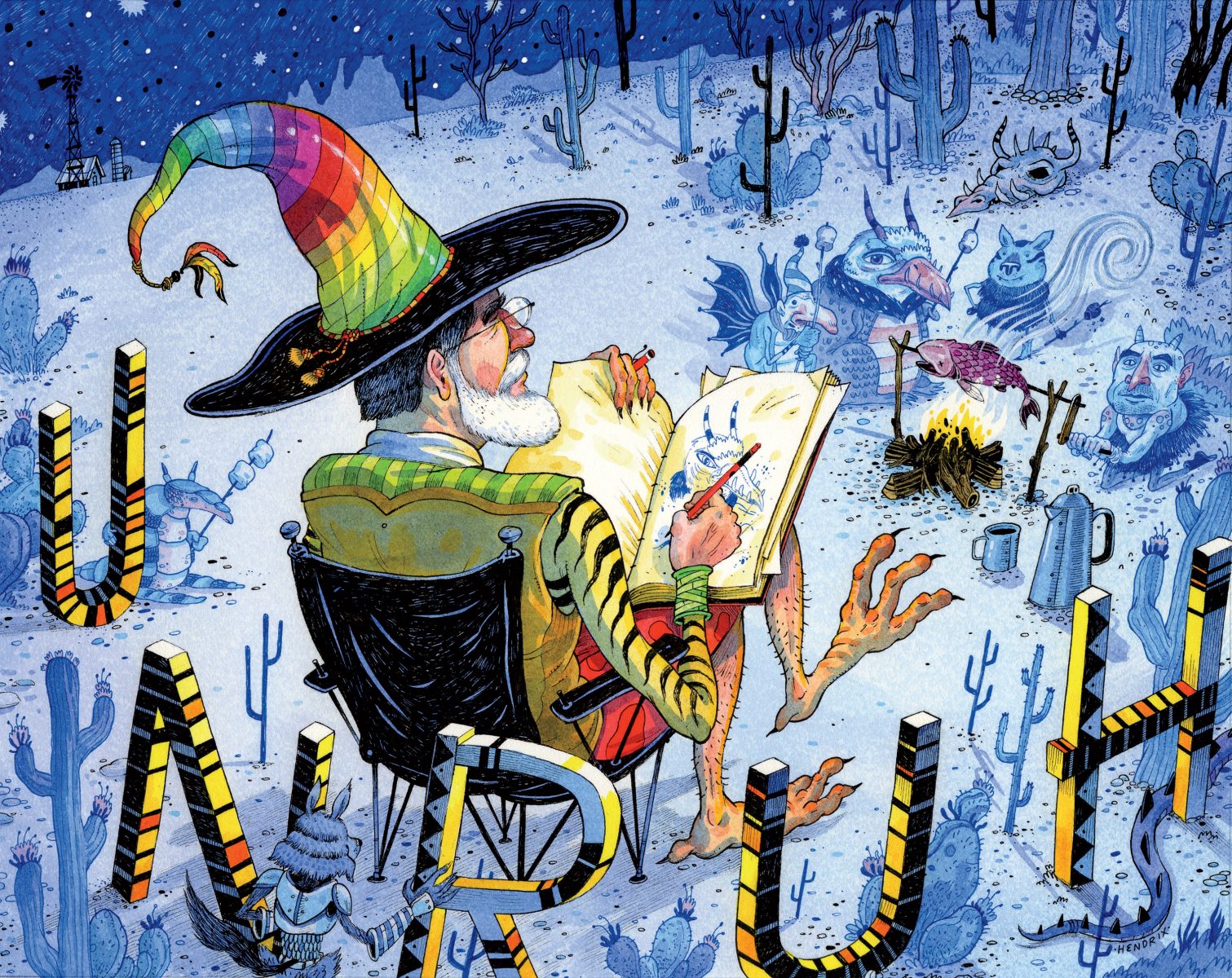

Four illustrators and one writer pay tribute to the late Jack Unruh, an artist for the ages

After seeing the first six illustrations Jack Unruh drew in 2003 for my column in Field & Stream, Mom had had enough. “Why does that man always draw you with that big red nose?” she cried. “You’re a good-looking boy!” I was in my late forties but remarkably youthful-looking. She even wrote him a letter about it. He responded by making my nose bigger and redder. That was pure Jack. While he was an absolute gentleman, they were his damn illustrations. (I envied his masterful use of profanity, which he could get away with in situations where you couldn’t. It wasn’t obscene. It was the profanity of emphasis and exuberance.)

More recently, Jack similarly provoked the fly-fishing great Lefty Kreh with a portrait. Unlike Mom, Lefty wasn’t one to mince words. Further, they would soon meet at a Dallas dinner party. Lefty approached and was about to lay into him when Jack handed him my mother’s letter. He’d kept it all those years. The legendary fisherman—a fly he invented graces a U.S. postage stamp—read it. He chuckled. Situation defused. Later, Lefty came over and asked, “Jack, mind if I see that letter again?”

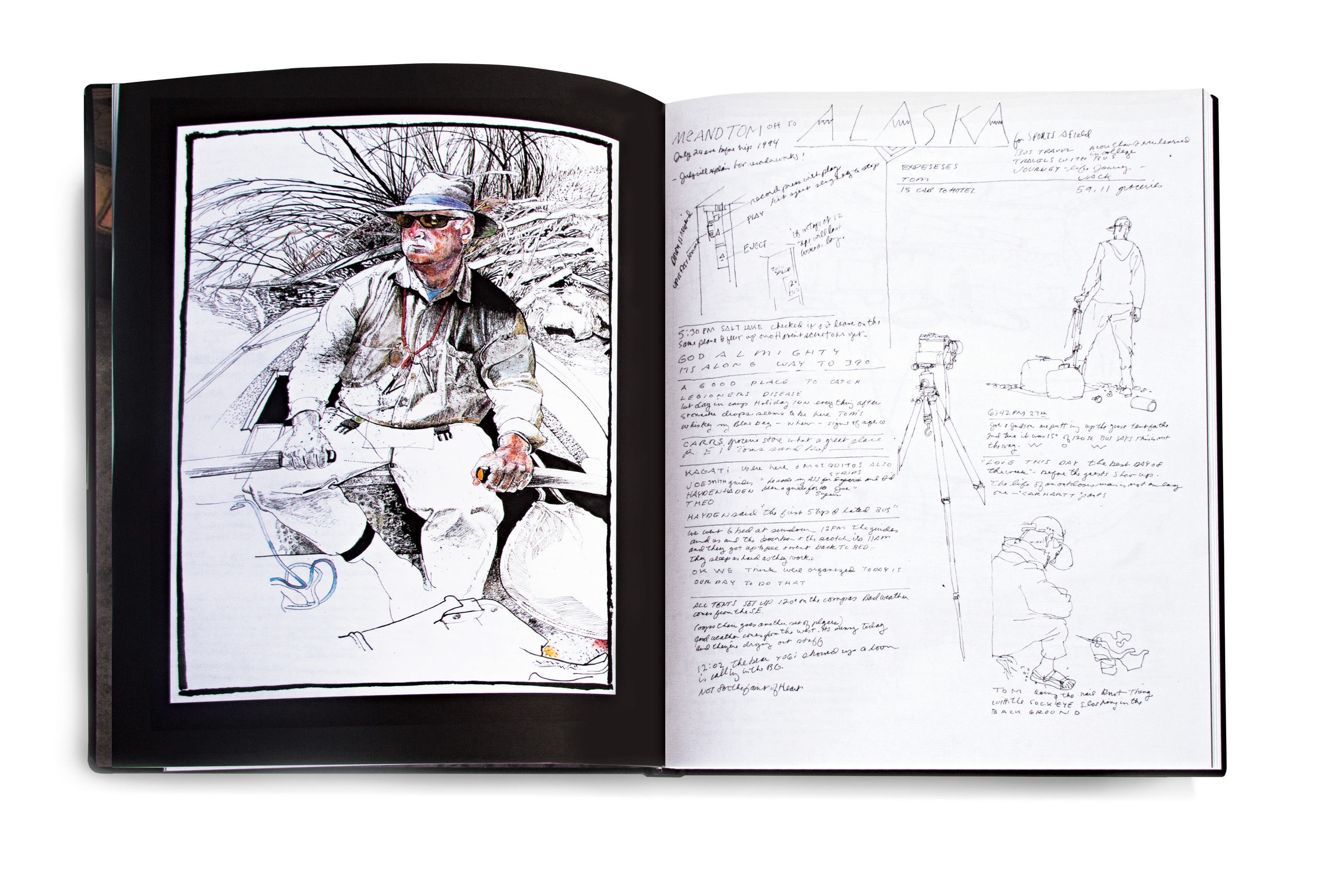

Illustration: Joe Ciardiello

Jack the Duck Hunter

"Jack always brought his A-Game, regardless of the assignment... an illustrator's illustrator. I'm grateful for his inspiration, his generosity, and that hearty laugh as big as Texas."

Jack Unruh died in May at the age of eighty, following a short battle with cancer. Born in 1935 in Pretty Prairie, Kansas, Jack couldn’t remember a time he didn’t doodle (his word). He’d lie on the rug drawing what he heard on the radio, stories about the war, the adventures of Sky King and Captain Marvel. Unlike other kids, he forgot to grow out of it. An Air Force brat, always on the move—four different schools in first grade alone—he was the new kid, the odd one who sat in the back and doodled. His father, a decorated bomber pilot, loved to fly. Jack soared on the wings of his pen in the limitless sky of a blank page. There was a purity to Jack, personally and professionally. He had a sublimely twisted sense of the absurdity of life. But he also had a kind of innocence. He never lost his wonder and gratitude that people would pay him to doodle.

When he was thirteen, two of his father’s friends lent him an old Winchester Model 97 shotgun and also taught him to fish for trout. He fell in love with all of it, fish, rivers, birds and bird dogs, landscapes. He set his sights on becoming a game warden. His father pointed out that wardens worked hunting and fishing seasons. They also got shot at sometimes. Maybe you could be an artist, his dad suggested.

Illustration: John Cuneo

Jack the Quail Hunter

"Jack was not your typical illustrator, shackled to a computer and scrolling through Google Images for nature references. He was a guy for whom 'back to the drawing board' usually involved pissing on a campfire."

Good advice, as it turned out. After college, thinking he couldn’t compete in New York or Los Angeles, Jack set up in Dallas. He needn’t have worried. His work began appearing everywhere—Time, Rolling Stone, the Atlantic, Entertainment Weekly, Texas Monthly, GQ, Field & Stream. His frequent illustrations in Garden & Gun ranged from George H. W. Bush in a Texas diner to brook trout in the Smokies. He illustrated a book of bird poems by Pablo Neruda, drew flowers at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. National Geographic sent him to Lascaux for weeks to illustrate prehistoric cave paintings. But he also drew what he saw in his mind’s eye. A hulking silverback gorilla in cowboy boots striding across a corral about to snap the chain in the hand of a miniature barefoot cowhand, a chicken that has just laid a broken egg whose yolk is a detailed half globe showing the Northern Hemisphere. He won every award an illustrator can and is in the New York Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame.

We were as likely a pair as Roy Rogers and Gordon Gekko, but I adored the guy. Jack was a happy, optimistic man, comfortable in his own skin. People responded to that. He seemed to befriend everyone he ever met. I’m guarded, sarcastic, anxious, pretty sure that nothing’s going to be okay. I have all the charisma of a box turtle. There’s a soft heart underneath, but it’s not on public display. His wife, Judy Whalen, once told me Jack saw right through me and liked my sense of humor. I once overheard him describing me to a friend. “What’s Heavey like? Well, we were hunting quail once, staying in this shithole motel in a West Texas town. Had a Dairy Queen and a Mexican restaurant you didn’t want to eat at twice. But the desk clerk kept telling us that there were restaurants around serving any kind of food we could think of. Just wouldn’t put it down. He tells Heavey, ‘Go ahead. Just name any kind of food you like and I’ll tell you a restaurant that has it.’ And Heavey looks at the guy with a straight face and says, ‘Armenian.’” And then Jack laughed his big laugh.

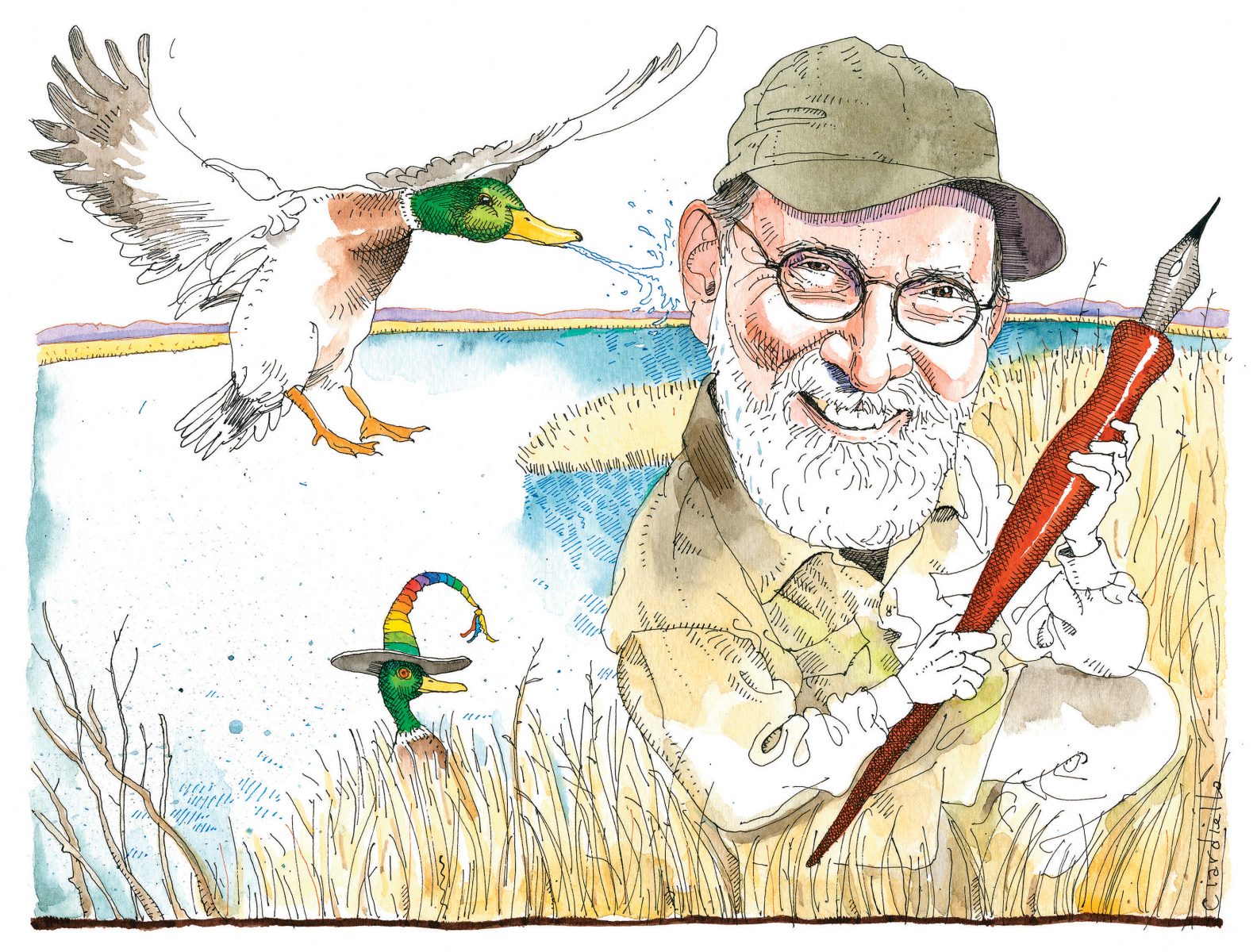

Illustration: John Hendrix

Jack the Campfire Sitter

"Some of my favorite moments in Jack's drawings were the appearances of his little fairies and sprites in the margins. They always reminded me just how much he loved to draw. Here he is drawn as one of his favorite recurring gremlins, the rainbow-hatted Li'l Bubba."

We fished for trout and smallmouth in Wyoming and West Virginia, hunted quail in Texas, pheasant in South Dakota. To see him hunched over his sketchbook in the field was to see a man doing exactly what he’d been put on earth to do. I passed him once seated on a log by a trout stream on a weeklong trip in the Wind Rivers. It was noon, not great light for an artist, and the spot seemed pretty enough but unexceptional. It was only months later, when the illustration ran, that I saw what I’d missed. A particular cluster of boulders in the water was alive. The rocks had faces and expressions and moods. And although the drawing expressed a single moment, you understood that the expressions and moods changed as the light changed. I have no idea how he achieved this.

Jack’s drawings never looked “serious,” but he was incredibly demanding of himself, often throwing away early versions of illustrations and reworking later ones until they met his standards. This was a three-part deal. That the work fulfill the client’s requirements was a given, the easy part. The picture also had to be the best he could do. There was no excuse for anything less. Why should there be? Third, the work had to be recognizably his. Why shouldn’t it be? Since commercial illustrations are often unsigned, this was a matter of technique—composition, color, the use of white space that made what was there that much more important. Those standards, as much as innate skill, were what made him. Even an unschooled eye like mine recognizes a Jack Unruh picture.

Illustration: Tim Bower

Jack the Fisherman

"How to depict Jack fishing? Sitting in a boat or wading into a river current just wasn't working. A dozen sketches later it occurred to me why––Jack is no longer tethered to Earth's gravity. And come to think of it, he never was."

All great artists are sneaky. Jack would put his face on a figure at the edge of a crowd or disguise his signature. He had a particular gift for composition, for placing the wildly disparate elements of a picture into something greater than the sum of its parts. In a class he taught at East Texas University, a student once asked about this. Jack pulled himself to professorial height. “Dynamic composition in a drawing,” he began, “is what allows me to strategically hide a neat little motherf***er peeing my name in a snowbank where a client won’t see it until the check clears and the illustration is printed.”

That line is both subversive and professional. It uses barbless profanity to make a serious point about detail. It’s funny. And any illustrator or art director in the country who heard it knows there’s only one guy who could have said it: Jack Unruh.

Click here to see a slideshow of Jack Unruh’s work in Garden & Gun.