Made in the South Awards

Meet the Winners of the 2022 Made in the South Awards

A stunning North Carolina–made modern curio cabinet, a best-ever buttermilk biscuit mix, a surprising Georgia-inflected port, and twenty-one other Southern-made products compose this year’s crop of honorees across six categories—home, food, drink, crafts, style, and outdoors. Plus: Our first ever Sustainability Award winner

Overall & Home Winner: Elijah Leed Studio

Warren Cabinet

Durham, North Carolina | $8,000; elijahleed.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Treasure Chest

An envy-inducing statement piece puts a contemporary spin on the classic curio cabinet

By Caroline Sanders Clements

Behind the luminous bronze screen and the handsome dark walnut casing of Elijah Leed’s Warren Cabinet, pottery, art books, trinkets, and turtle shells are meant to nestle next to model ships, marbles, and Matchbox cars. “The driving narrative for this piece was the notion of having something tucked away that’s not completely hidden,” says Leed, a designer in Durham, North Carolina. The premise has been around for centuries: Cabinets of curiosities have existed since the Italian Renaissance, when collecting rare and unusual souvenirs from the world over indicated social status, and viewing the assemblage doubled as party entertainment.

But for a segment of the audience who saw Leed’s sleek and modern finished design at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair (ICFF) in New York last spring, a classic American piece sprang to mind. “Some of the older-generation folks I know said it looked like a pie safe,” Leed recalls. “That was the first time I heard a reference to that.” While he didn’t intentionally fashion the cabinet after the folksy eighteenth-century kitchen essential conceived to protect food from insects and animals in the days before refrigeration, he doesn’t mind the comparison. In fact, Leed believes that he—and every other artist and artisan—is constantly being influenced by one thing or another, whether or not he realizes it.

“The folks who try to say that they are inventing something new—I don’t subscribe to that,” Leed says. “I wanted to make a recognizable object, but in a new way. [The cabinet] is not entirely brand-new, but I think a lot of the small details of what our team implements in the work set it apart.” And despite the cabinet’s resemblance to time-tested forms, its refined elements—integrated joinery in figured walnut, a delicate woven (not welded) bronze screen, hand-cast bronze pulls to match—demanded innovation.

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

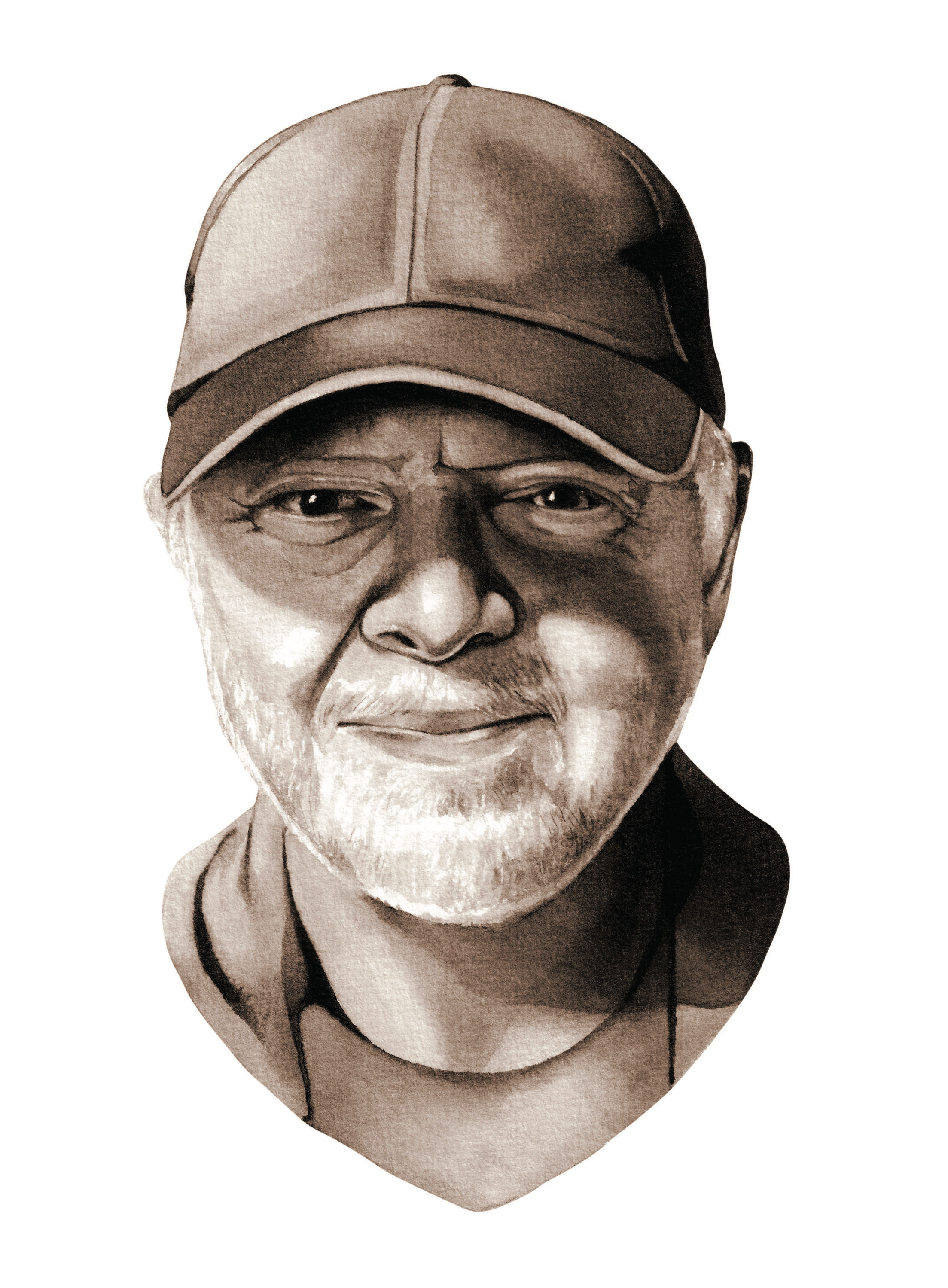

Elijah Leed, in his Durham, North Carolina, workshop.

Before beginning his career in woodworking, Leed studied glassblowing and sculptural ceramics at Centre College in Kentucky, and he approaches each furniture project with an artist’s eye. In his workshop in downtown Durham, in a building that also accommodates his metal fabricator, an arts nonprofit, and a glassblowing studio he and a friend opened in 2017, Leed began by sketching out a handful of cabinet styles. One was tall; one short; one squat and square. “There’s no formula for any of this,” he says.

After settling on the Warren’s current shape and dimensions, he collected materials, obtaining rough-cut walnut from nearby Gibsonville before milling and shaping it in-house. “We use a lot of walnut in our furniture,” Leed says, noting its resilience, malleability, rich hues, and intricate grain. “I spend a lot of time traveling around and picking up extra walnut whenever I see it. Almost all of our material comes from somewhere in Appalachia.”

Although most of the tables, shelves, lounge chairs, and credenzas Leed creates rely on hard angles, shaping the cabinet’s curved edges came relatively easily. “But wrapping the bronze around that curved end was an entirely new ball game,” he says. “It was trial and error in getting that correct, but honestly, it was a lot of fun. Most of the time we’re working on something we’ve done before. This was something we had to figure out.” Pulled tight and secured, the screen has a twinkle to it, as any treasure chest should; at the ICFF, attendees couldn’t help but reach out and touch the metal as they walked by.

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Leed hand planes the edge of a dovetailed board for a drawer.

The hardware, topped with thumbprint-like indentations, also invites contact. For the pulls, Leed whittled a wooden form before crafting a silicone mold around it. He then worked with a local jeweler to cast them in bronze. “Most of the other pulls we make are just round,” he explains. “They’re turned on a lathe and have a much more polished look. These were important to me because they look distinctly handmade.”

In someone else’s hands, the gleaming wood, glitzy screen, and shiny custom hardware might feel showy, but Leed’s strength is his subtlety. “I want to make sure my work is unique, but not necessarily in a dramatic way,” he says. Intentional and impressive in their own rights, the cabinet’s components dazzle when compiled, just like the cherished collections it’s meant to store.

Home Runner-Up: Heart & Spade Forge

Carbon-Steel Baker Set

Roanoke, Virginia | Sets from $800; heartandspadeforge.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

When most of his peers were working on their T-ball swings, Jed Curtis acquired his first anvil, inspired by a blacksmith demonstration he saw on a field trip to a living history museum. “I never really considered that it would be a job, though,” Curtis says. But after a chance encounter with a retiring New York blacksmith, who sold him the contents of his shop, Curtis settled in Roanoke in 2016 and opened Heart & Spade Forge. There, he hand forges carbon-steel cookware—such as these elegant bakers—out of raw steel he procures from North and South Carolina, as well as from a mill down the street from his workshop. He designs the bakers—sold individually and in a trio—to distribute heat evenly, either in an oven or on a stove, and transition seamlessly to the table. His chemistry degree informs the pieces’ functionality (carbon steel allows more temperature control than cast iron), and he brainstormed aspects of their form by watching Colonial Williamsburg silversmiths and 1940s hot-rod builders. But mostly, the idea of legacy drives his work. “A family skillet is a unifier,” he says. “I’m not as much making them for you as I’m making them for your grandkids.”

Home Runner-Up: Ben & Lael

Silver Bowl with Antler Stand

Nashville, Tennessee | From $1,950; benandlael.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Although Ben Caldwell grew up around silver—his father was an avid collector, and he spent many childhood Saturdays riding along in search of treasures—his decision to become a silversmith surprised him. “For the first part of my career, I built musical instruments,” he says. But when Terry Talley, a metalsmith in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, asked if he would be interested in apprenticing, Caldwell’s career pivoted. Today he creates handsome silver and copper tableware and other home goods under the name Ben & Lael, including these gorgeous bowls, which he hand pounds before passing them off to Keith Leonard, the owner of a local plating company, who quadruple plates them in silver. (Caldwell crafts his copper and sterling pieces entirely in-house.) “When you hand make a bowl, it is naturally round, but in order for it to work in a home, the bottom has to be flat,” Caldwell says. “I hated disrupting the form to make it functional.” His solution: expertly balanced stands pieced together from naturally shed mule deer, white-tailed deer, moose, and elk antlers. “Antlers are extremely elegant and biomorphic,” he says. “They’re a sculptural form. Functional but also fine art.”

Home Runner-Up: Reid Classics

Mahogany Four-Poster Bed

Dothan, Alabama | From $4,300; reidclassics.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Despite the intricacies of the sophisticated four-poster beds that Andrew Reid and his Reid Classics team produce in their Dothan, Alabama, workshop, the machines they operate are simple. “My shop is a working, running museum full of antique equipment from the forties and fifties,” Reid says of his cast-iron devices such as a planer originally commissioned by International Harvester and a band saw salvaged from a World War II aircraft carrier. “They work better than anything new. We start with rough slabs of primarily mahogany from Central and South America and start milling.” From there, even his simplest design takes ninety-six steps. Since 1938, the now third- (going on fourth-) generation company—Reid’s teenage children are starting to learn the business—has put that kind of effort into pencil post (pictured), colonial-style, spool, and Victorian beds for homes across the country: Alabama farmhouses, Hollywood villas, Charleston manses, and contemporary New York flats. “I have a client in Birmingham who’s ninety-six years old, and she sleeps in the same bed she got from my grandfather for her wedding present,” Reid says. “They’re made to last forever.”

Food Winner: Biscuit Head

Buttermilk Biscuit Mix

Asheville, North Carolina | $8.50 per bag; biscuitheads.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Easy Bake

Whip up Carolyn and Jason Roy’s famously fluffy catheads at home

By Wayne Curtis

“Biscuits are such a great comfort food, and there’s so much you can do with them,” says Carolyn Roy. She and her partner, Jason, prove just that at Biscuit Head, their breakfast-and-lunch spots where diners can go to town on the baked goods, dressing them up with one of a half dozen gravies, or with offerings from the hot sauce and jam bar, or with fillings such as pulled pork, country ham, and, in the case of the “Filthy Animal” biscuit, homemade pimento cheese, fried chicken, bacon, and scrambled eggs, all slathered with the house gravy. “That one is ridiculous,” Carolyn admits.

But it all comes back to the base: Since the Roys established their first location in Asheville in 2013, their large, ethereal, and delicious cathead-style biscuits have beckoned the breakfast bunch. Not long after they opened, customers began to ask for their mix. The Roys obliged, selling it in mason jars with instructions attached on a ribbon.

Now that mix has gotten a makeover. As Biscuit Head’s popularity has continued to soar, the Roys have expanded to two other Asheville locations and one in Greenville, South Carolina, and have also opened a canning house, where they now make their jams and newly bagged no-fail biscuit mix. The key here: They’ve already cut in the butter; home cooks need only stir in some buttermilk, which makes it easier to keep flour in the bowl and off the counter (and, well, everywhere else in the kitchen). Simply drop (don’t roll) the dough onto your pan, says Carolyn, and don’t skimp on the scoop. “Our biscuits are really light and fluffy on the inside and buttery and crunchy on the outside,” she says. “You can’t pick them up and eat them with your hand. They’re knife-and-fork biscuits.”

Food Runner-Up: Poppy Hand-Crafted Popcorn

Poppy x Spicewalla Popcorn

Asheville, North Carolina | $7–$9.50 per bag; poppyhandcraftedpopcorn.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Ginger Frank knew she wanted to run her own business before she had even given much thought to what that business should be. But she loved popcorn and saw that Asheville lacked a vendor dedicated to the snack. So, despite the deeply furrowed brows of friends and family, she opened a store called Poppy Hand-Crafted Popcorn selling gourmet specialty popcorn in creative flavors. “It was pretty much my one and only idea, so it really needed to work,” Frank says. It did. She used natural ingredients and spices (“you can pronounce everything on the label”), and Asheville took notice. She now has fifty-six employees and says she could use another ten. Many of her most popular versions have come from collaborations with local and regional businesses. Among them: Spicewalla, Asheville chef Meherwan Irani’s line of high-quality, small-batch spices, which led to the new Poppy x Spicewalla collection. The bold series comes in four flavors, including craveable caramel Chai Masala and spicy, smoky Piri Piri.

Food Runner-Up: Butcher & Bee

Smoked Onion Jam

Charleston, South Carolina | $13; shopbutcherandbee.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Smoked onion jam has appeared on the menu at the Middle Eastern–accented Butcher & Bee restaurant in Charleston for more than a decade. Originally created as a condiment for the roast beef sandwich, the jam stuck around in part because it was so adaptable—it’s since appeared in cameos on the cheese board and atop plates of brussels sprouts. Customers ask for it on nearly everything else, and then request small containers to go. So proprietor Michael Shemtov decided to start selling the standout, made from onions taken from a smoker and then cooked down with sugar and water, in jars for fans to enjoy at home. “You can put it on a burger, on fancier food, make it part of breakfast or part of dinner,” Shemtov suggests. And for vegetarians, it substitutes beautifully for bacon, adding layers of smoke, sweetness, and umami.

Food Runner-Up: Life Raft Treats

Not Fried Chicken

Charleston, South Carolina | $5–$6 per piece; $100 for a bucket of nine; liferafttreats.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Cynthia Wong was feeling burned out. A pastry chef nominated six times for James Beard Awards, she was growing weary of the long hours and constant grind of restaurant life. She decided to launch her own business and began brainstorming. One of the advantages of utter exhaustion, she says, was that she had “no resistance to creative thought. Not Fried Chicken is one of the things that I came up with as a delirious, overworked chef.” The vision for the utterly delightful concoction—an ice cream goody that looks like a fried chicken drumstick—arrived during a nap, fueled by recollections of a trip to France, where she’d tasted amazingly inventive ice cream confections. Experimenting led her to waffle-flavored ice cream wrapped around a chocolate cookie “bone,” all coated in crunchy caramelized white chocolate and a cornflake coating to complete the delicious illusion that thrills children and adults alike. The drumsticks, which she makes for her company Life Raft Treats, are available individually at select stores across the South (including Whole Foods), or by the bucket nationally from Goldbelly.

Drink Winner: Chateau Elan Winery

Bianco American Riserva Port

Braselton, Georgia | $75; chateauelan.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Toast of Georgia

Old World meets New in a surprising, superlative white port

By Wayne Curtis

Chateau Elan Winery and Resort opened in 1982 in Braselton, Georgia, with six hundred acres to expand and the ultimate aim of becoming one of the largest wineries on the East Coast. Climate and topography had other plans. “The problem wasn’t in the winemaking, but in the grape growing,” says Simone Bergese, Chateau Elan Winery’s CEO and executive winemaker. After years of disappointing harvests, the winery had just twenty acres in vines. Then, in 2012, in came Bergese, who grew up in Italy’s Piedmont region and began working at wineries at age eighteen with subsequent stints in Australia, Sicily, and Virginia. “I passed through the gates and looked at the property,” he says, “and I knew there was incredible potential.”

Bergese began to make a white port in addition to other wines, replacing the Old World grapes with muscadine, a native variety well suited to the South. For his port, he settled on a blend ratio of 30 percent muscadines to 70 percent chardonnay grapes shipped from California in refrigerated trucks. He used traditional methods, halting fermentation early by adding a high-proof grape spirit before the sugars had all converted to alcohol. His port was good, but on a 2019 trip to visit Portuguese wineries, he realized that aging the wine in barrels a little longer would improve his results. “After tasting what a white port could be, I decided to wait a bit more before bottling,” he says. The delay proved worthwhile, coaxing forth a beguiling natural sweetness that complements the fortified wine’s earthy praline notes. And while quantities are limited, and currently Chateau Elan only sells the port on-site and online, the winery has ramped up production, meaning more bottles will find their way to shelves over the next few years.

Drink Runner-Up: Stone Hollow Farmstead

Strawberry Rose Drinking Vinegar

Harpersville, Alabama | $18.50 per bottle; stonehollowfarmstead.com

Fredrik Brodén

In 1999, Deborah Stone and her husband bought an eighty-acre woodland outside of Birmingham and, with the help of her father, gradually converted the spread to a farm. They grew roses and other plants for skin-care lines: Stone had spent her early career in the spa and wellness world—and she had also owned a juice bar for a time. “That’s where I became familiar with shrubs and drinking vinegars and their benefits,” she says. Using produce and herbs grown on the farm, she now concocts vinegar flavorings, such as blueberry and turmeric, for her Stone Hollow Farmstead and its retail outpost in downtown Birmingham. Three years ago, she rolled out her strawberry and rose version, and it took off, becoming the company’s top-selling drinking vinegar. The farm has about three thousand strawberry plants, and the fresh berries get macerated in organic apple cider vinegar. Stone then augments this mixture with rose petals, peppercorn, coriander, and cinnamon, which brings it a distinct pop. Cooks can use it for salad dressing; bartenders should try it in cocktails. But it can also be enjoyed simply, with a little bubbly water over ice.

Drink Runner-Up: Back Pocket Provisions

Bloody Brilliant Bloody Mary Mix

Richmond, Virginia | $36–$50 for a four-jar collection; backpocketprovisions.com

Fredrik Brodén

Will Gray found his way into the Bloody Mary mix business through a bit of reverse engineering. He’d been working for a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., focused on making agri- cultural systems more sustainable, and was looking for a way to bring fun and joy to a commodity-dominated world. “Bloody Marys have been part of my family’s celebrations as long as I can remember,” Gray says. “I knew what a Bloody Mary was before I knew what a cocktail was.” He also knew a lot of small family farmers who grew heirloom tomatoes that “sold well when perfect, but not at all when imperfect.” He and his sister Jennifer Beckman started Back Pocket Provisions in Richmond in 2015 and began juicing unloved tomatoes from their network of family farms across Virginia. To create their flagship mix, Bloody Brilliant, they balance the fresh juice with horseradish, Worcestershire sauce, and cayenne pepper. “We wanted to make something that drinks like the juice of a tomato, rather than something more viscous like V8,” he says. The resulting bright, light flavor tastes more of the field than the jar.

Drink Runner-Up: TX Whiskey

Texas Straight Bourbon Whiskey Finished in Cognac Casks

Fort Worth, Texas | $65; frdistilling.com

Fredrik Brodén

The boom in craft distilleries across the South (and the nation) paved the way for another boom: a rise in experimentation in making whiskey and other spirits. Smaller distilleries tend to be more nimble, able to try a variety of new approaches to see what works. TX Whiskey sits on 112 acres in Fort Worth, and since the brand’s founding in 2010, has quickly earned a reputation for producing quality bourbon. It’s also embraced that spirit of innovation: Last November, the distillery released the third in its Barrel Finish Series, resting its aged bourbon in used cognac casks for more than a year. The casks add fleeting notes of dense fruit, which blend sublimely with the vanilla and caramel flavors served up by traditional oak barrels. “It’s a perfect summer bourbon,” says Ale Ochoa, the distillery’s whiskey scientist, “because it has more of the lighter, crisper fruity notes.”

Crafts Winner: The Acadian Weaver

X and O Coverlet

Baton Rouge, Louisiana | $2,000; theacadianweaver.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Threads of History

In Louisiana, a weaver and his mentor uphold 250 years of Cajun textile tradition

By CJ Lotz

With each fiber he spins into thread, each warp he ties to the loom, each swatch he dips into indigo dye, and each hour he spends driving the back roads near his home in Baton Rouge to collect blanket patterns, Austin Clark keeps alive the centuries-old art of Acadian weaving. Clark and his mentor, an eighty-one-year-old weaver named Elaine Bourque, have studied museum collections and interviewed dozens of folks to gather examples of the textile patterns the Acadian people (the ancestors of today’s Cajuns) wove in the 1700s, 1800s, and early 1900s. Brown cotton, which Acadians historically used for clothing and blankets, is a living marker of that legacy—Bourque still grows rows of the caramel-hued variety, and Clark works it and his own crop into his Acadian Weaver items whenever possible.

His productions include classic striped designs that often decorated the towels, blankets, and sheets found in Cajun trousseaux, as well as a historic X-and-O-pattern blanket that weavers sometimes made with costlier all-white cotton as a special wedding gift. The pattern traces to Thérèse Dronet, an Acadian spinner and weaver who presented her “cross and diamond” bedspreads to First Ladies Lou Hoover and Mamie Eisenhower. “I re-create as close to the originals as I can,” says Clark, who releases smaller textiles monthly while clients must commission larger pieces like the blankets, which can take a few months to complete. “It’s important to not put my own spin on it, because I’m not Cajun. I want to respect the culture, respect the weavers, and let the work speak for itself.”

But Bourque, a Louisiana Folklife Tradition Bearer honoree, will speak for Clark’s talents: “I feel happy and content knowing Austin will continue the tradition in the same manner as my ancestors,” she says. “The Acadian tradition is in good hands.”

Crafts Runner-Up: Audiowood

Black Barky Turntable

New Orleans, Louisiana | $1,850; audiowood.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Joel Scilley’s audio creations are both devotedly old-school and way ahead of their time. He’s been building the exquisite record players since 2008, long after vinyl’s initial heyday, but before its recent revival (vinyl sales just enjoyed their biggest year since the 1980s). “I like to think I had a small part in helping that resurgence along,” says Scilley, who lives in New Orleans and counts among his Audiowood clients acclaimed interior designers, prominent Southern musicians, and actors—one of his turntables even made it into the film Star Trek into Darkness. For his Barky turntable, Scilley wields his background in art, architecture, design, and woodworking to shape an elegant music machine featuring ash-wood rounds from a family logger who has perfected a curing process that eliminates cracks. Scilley sands the wood round to a precise flatness, and then partially ebonizes it before sealing it with several coats of finish—no record skips here. He then fits the turntables with top-grade audio parts and ships them to music fans all over the world. The Barky looks like a modern marvel, but spin some Allen Toussaint on it, and you might find yourself forgetting about your Spotify subscription.

Crafts Runner-Up: People Via Plants

Ceramic Mugs

Richmond, Virginia | $45–$55; peopleviaplants.com

Fredrik Brodén

Overlap the skills of a sculptor and a fine-art painter and you’ll get People Via Plants’ Technicolor collection of ceramics. Matt Spahr and Valerie Molnar both taught at Virginia Commonwealth University, where the then sculptor and painter (respectively) discovered that they work well as collaborators. So they joined their talents to create bright planters, vases, and mugs that sell out quickly online and in stores. Their process involves making molds using a computerized router, slip casting with clay, and embracing surprises. “For the mugs, the initial shapes have these textures to them, dictated by the drill bit of the router,” Spahr says. “In mold making, you usually do a rough pass and then smooth it out on the final, but we decided to keep the dimples.” They added a funky yet functional square handle and then splashed them with an incredible array of glazes. “On our Gozer and Gozarian mugs, named after Ghostbusters characters, we’ll fade colors like sunsets and sunrises,” Molnar says. Another glaze pattern references the tulip poplar tree, but Molnar’s camellia garden also inspires, as do walks through the River City Flower Exchange, Richmond’s all-local floral market.

Crafts Runner-Up: Bright Black

Candles

Durham, North Carolina | $30–$40; brightblackcandles.com

Fredrik Brodén

“We tell stories through scents,” says Tiffany Griffin, who with her husband, Dariel Heron, launched Bright Black candles in Durham in 2019. A former government worker in Washington, D.C., Griffin got motivated by back-to-back shutdowns to move back to North Carolina and create a business plan for her family’s financial freedom, choosing to honor their adopted hometown with a unique line of candles. “The Durham candle has scent notes of tobacco, cotton, and whiskey,” she says. “It was my first and is still one of my favorites.” Within three short years, Bright Black has created a partnership candle with the NBA as well as a Diaspora series that includes a Kingston candle with hints of rum and grapefruit that celebrates Heron’s Jamaican roots. They’ve also anchored their business in important causes—a portion of sales from their summertime candles support Black-led outdoors groups in the South. And this fall, Bright Black expanded its studio to include a community creative space, where it will hold candle-making and scent workshops.

Style Winner: Miranda Bennett Studio

Sustainable Women’s Wear

Austin, Texas | $18–$468; shopmirandabennett.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Go with the Flowy

This ethically sourced clothing charms women of all shapes, sizes, ages, and skin tones

By Elizabeth Hutchison Hicklin

“I wanted to learn from the pain points I experienced the first time around,” says the designer Miranda Bennett of launching her namesake sustainable clothing brand. A native of Austin, Texas, Bennett has a degree from Parsons School of Design and spent twelve years in the New York fashion world, but her vision for a more eco-friendly, ethical apparel company that minimized waste and environmental impact didn’t truly gel until she discovered plant-based dyes upon her return to her hometown in 2013. “As I started to learn about plant-based dyes, I began sewing again and dying things with my own hands,” she says. “It just suddenly felt like this whole different reason to have a collection.” In the years since, she’s gone a step further by exploring zero-waste plant-based dyes and partnering with a range of businesses, from local Japanese restaurants to sawmills, to cull materials for the process such as avocado pits and pecan shells.

With those dyes as a springboard, Bennett dove deep into the world of slow fashion. She committed to sewing and constructing everything within Austin’s city limits and eschewed seasonal trends in favor of a smaller collection of timeless, well-made silhouettes that last. “It’s all about draping,” she says. “We make pieces that are deceptively simple, but we have several styles you can wear upwards of five different ways.” The designs feel as good as they look thanks to the brand’s exclusive use of natural fibers—organic cotton, silk, and linen. And no matter your taste or shape, there’s most likely a Miranda Bennett style for you. “Our collection is about making every wearer feel their absolute best,” Bennett says. “So how could we leave people out because of size or age?”

Style Runner-Up: Glad & Young

Fanny Pack

Atlanta, Georgia | $145; gladandyoungstudio.com

Fredrik Brodén

Glad & Young founders Erica Tankesley and Anna Zietz both grew up in creative households. “We loved making and creating things for ourselves,” Zietz says. As their artistic partnership grew, they began experimenting with different materials but quickly realized they loved working with leather. And while a lot of leather goods run toward traditional and masculine, Glad & Young’s line of colorful handbags and accessories feels playful and fresh—none more so than the best-selling fanny pack. “Hilariously, this bag started as a commission for a friend long before they were back in style,” Zietz says. But as the trend returned, sales of their leather fanny pack skyrocketed. Perfect for traveling or a night out, the versatile bag, which they make with U.S.-sourced leather and brass hardware, can be worn across the body, at the hips or natural waist, or thrown over the shoulder. The look comes in two sizes and a range of brights and neutrals, but the hand-marbled version really wows. “Marbling is such a magical process,” Zietz says. “We love the uniqueness it allows us to bring to each product.”

Style Runner-Up: Flint & Port

Hat Company

Bainbridge, Gerogia | From $550; flintandportco.com

Fredrik Brodén

Eldrick Jacobs’s undergraduate, graduate, and seminary degrees did not add up to a career of his liking. While doing some soul-searching, Jacobs took a door-to-door sales job in Cleveland. “I’ve lived in the South my entire life,” he says, “so the cold weather was a bit of a plot twist.” To keep the snow at bay, he bought his first hat. Fascinated, he began studying the craft before fate introduced him to an Ohio hatter who taught him the basics but encouraged him to develop his own style. So Jacobs returned to Bainbridge, Georgia, where he had grown up hunting dove, quail, and pheasant. There he found both inspiration and a devoted clientele in the hunters who flock to the area. “The outdoors shapes my aesthetic, and you’ll see me layering a lot of earth tones,” he says of his sophisticated Flint & Port designs. He makes his line of custom and ready-to-wear toppers, which he hand shapes using vintage tools, from rabbit, nutria, or beaver fur felt in styles ranging from classic dove-hunting silhouettes to brunch-ready fedoras to Mississippi Delta–inspired Gamblers. Not a hat person? Keep an open mind. “Confidence,” Jacobs says, “is the number-one ingredient.”

Style Runner-Up: Minnie Lane

Scarlett Bracelet

Nashville, Tennessee | $480–$11,720; minnielanedesigns.com

Fredrik Brodén

The North Carolina native Mimi Phillips, who worked as a wardrobe stylist and then as a creative coordinator for Ralph Lauren, blames Dolly Parton’s “fairy dust” for prompting her relocation from New York to Nashville. An early fascination with jewelry, which began with her mother’s and grandmother’s collections, took root in Music City, blossoming into a full-fledged brand after Phillips discovered the New Approach School for Jewelers. “It’s a world-class school just outside of Nashville,” she says, “with incredible teachers from Tiffany and the like. I did the full program—fine jewelry, stone setting, all the craftsmanship courses.” Soon after, she launched Minnie Lane, which first focused on fine-jewelry commissions but quickly pivoted to include her high-low line of fashion-forward rings, necklaces, earrings, and bracelets. Each design begins with a 2D sketch, which Phillips then brings to life via AutoCAD or wax before sending it off for casting. “Carving wax is like a meditation for me,” she says. Inspired by her friend Scarlett Baily’s Naked Everyday series of female nudes, she carved endless variations of the brand’s signature Scarlett bracelet—shown below at right with a selection of other Minnie Lane looks—before settling on the elegant yet whimsical design that has become a bestseller.

Outdoors Winner: Gary Lacey Rod Company

Edward vom Hofe–Style Fly Reel

Gainesville, Georgia | Starting at $2,995; facebook.com/Lacey-Rod-Co

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Reel Deal

A custom-made retro fly reel boasts modern appeal and heirloom good looks

By T. Edward Nickens

Gary Lacey started building fine bamboo fly rods thirty years ago in order to afford his love of the traditional material. “I figured if I was going to enjoy them, I’d better figure out how to make them,” says the Gainesville, Georgia, craftsman. In 2007, he added handmade fly reels to the mix. His fetching old-school salmon reels are near replicas of those produced by the acclaimed New York reel maker Edward vom Hofe in the late 1800s. Customers flip for “all the widgetry on these reels,” Lacey says, “such as the screws, the hand-turned drag knob, and the little poacher button that turns off the reel’s outgoing click. I think that’s why the old replica reels are so popular.”

To create his reels, Lacey turns to the same materials used in many of the original vom Hofe versions. He sculpts the reel’s side plates out of hard black rubber, the disc drag out of leather, and most of the rest of the components, including the signature S handle, out of nickel silver. He designs the three-and-a-half-inch reel, pictured here, for catching larger fish such as salmon, but Lacey makes vom Hofe–style reels in sizes down to trouty 4- and 5-weights. Each reel is bespoke—he collaborates with the client to build to his or her specifications. “It’s like ordering a custom shotgun,” Lacey says. “You want engraving? You’d rather not have an outgoing line clicker? You want a multiplier to take in more line with every handle turn? Every reel is made one at a time, so I can make them exactly how a customer wishes.”

Outdoors Runner-Up: Tekton Game Calls

Custom Duck Calls

James Island, South Carolina | From $200; tektongamecalls.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

A lifelong musician, Joey D’Amico played trumpet in grade school and earned a college scholarship working the valves of a euphonium. When he bought a wood lathe to help out on the restoration of a historic home in Charleston, South Carolina, the varied strands of his interests seemed to suddenly knit together. “I thought, if I could turn a baluster,” he recalls, “I bet I could make a duck call.” Today D’Amico guides waterfowl hunts from the Lowcountry rice fields to the Saskatchewan prairies and turns his Tekton game calls in a pole barn behind his house. He crafts his custom calls from exotic woods—bocote and African blackwood and stabilized maple burl. He also has a line of production acrylic calls for hunters watching their budgets. “I’ve made a lot of stuff,” D’Amico says. “But the call making hit me differently. I could be artsy and musical on one side but use my carpentry skills to play with tone channel length and exhaust openings and all the mechanics of how to make something that sounds like a duck.”

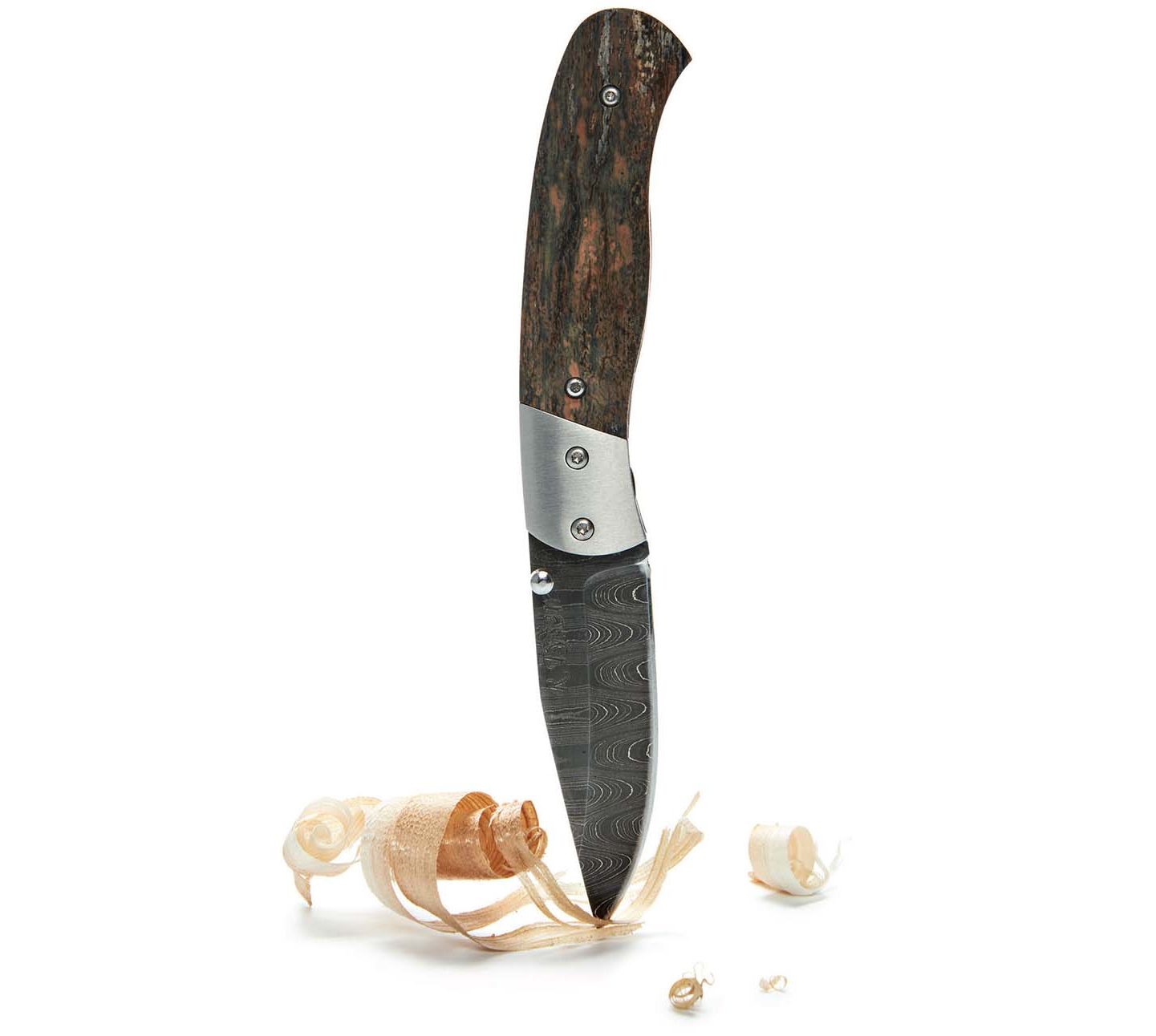

Outdoors Runner-Up: Ross Tyser Custom Knives

Sunday-Go-to-Meetin’ Folding Knife

Spartanburg, South Carolina | From $600; rtcustomknives.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

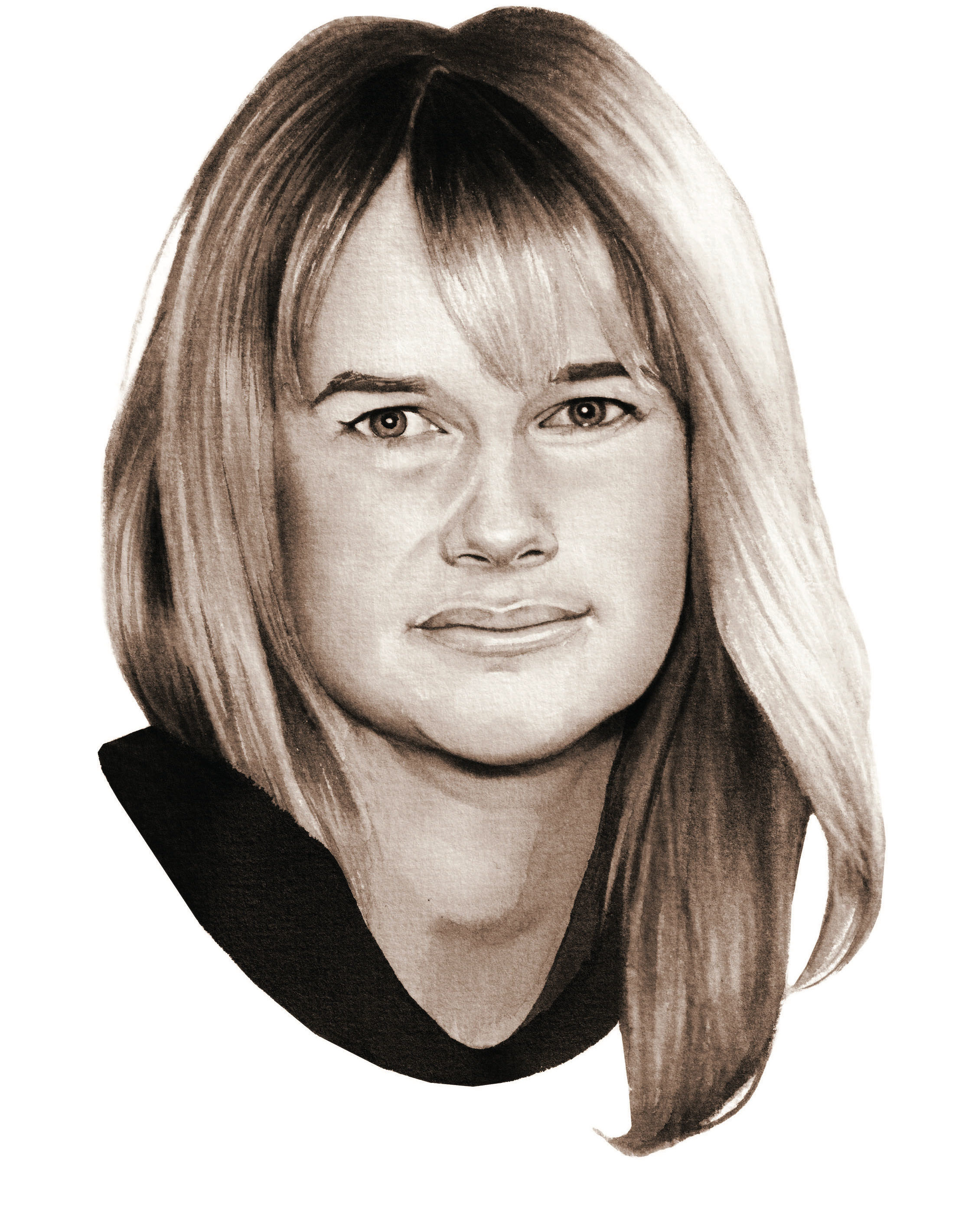

Ross Tyser’s custom small-bladed folder honors his grandfather, a master cabinetmaker who carried a small folding knife in the pocket of his suit vest every Sunday. “He would say that he just didn’t feel dressed until he had a knife in his pocket,” the Spartanburg, South Carolina, bladesmith recalls. With a two-and-a-half-inch blade of hand-forged, 384-layer Damascus steel, this sleek folder gets nearly as much attention from female customers as male. The mammoth ivory scales look stunning. The titanium liners are jeweled on the inside and hold a stout liner lock. With the exception of a few tiny screws, Tyser hand makes every piece using old-school tactics. He owns neither a power hammer nor a hydraulic press, staples in many knife-making shops. “It’s just my right arm, an anvil, and a few hammers,” he says. And memories of his grandfather, sitting on the front porch, listening to the Atlanta Braves on the radio while he carved wooden toys.

Outdoors Runner-Up: Southern Wood Paddle Company

Canoe Paddle

Charlotte, North Carolina | Starting at $265; southernwoodpaddle.com

Fredrik Brodén

For his hand-carved SouthernWood Paddle Company canoe, kayak, and stand-up paddles, the Charlotte craftsman Larry McIntyre melded a love of Southern history with a passion for spending time outdoors on the water. An avid paddler, he makes the pieces out of sinker cypress, the beloved old wood pulled from Southern swamps and streams, finding joy in the way “it ties me to the region.” He carved his first paddle in 2015 and went full-time four years later (he also makes sweet skateboard decks, boat hooks, and other items). For paddles, he starts with a plank of sinker cypress from an underwater logger out of Bishopville, South Carolina, cuts out the basic paddle form on a band saw, shapes the wood with a drawknife, and then hand planes and sands the piece. Each paddle gets finished with hemp oil. This particular canoe paddle sports a versatile modified beaver-tail shape and a protective epoxy tip that works well in shallow water. It’s a looker, whether plunged into a blackwater stream or mounted on the wall of a lake house.

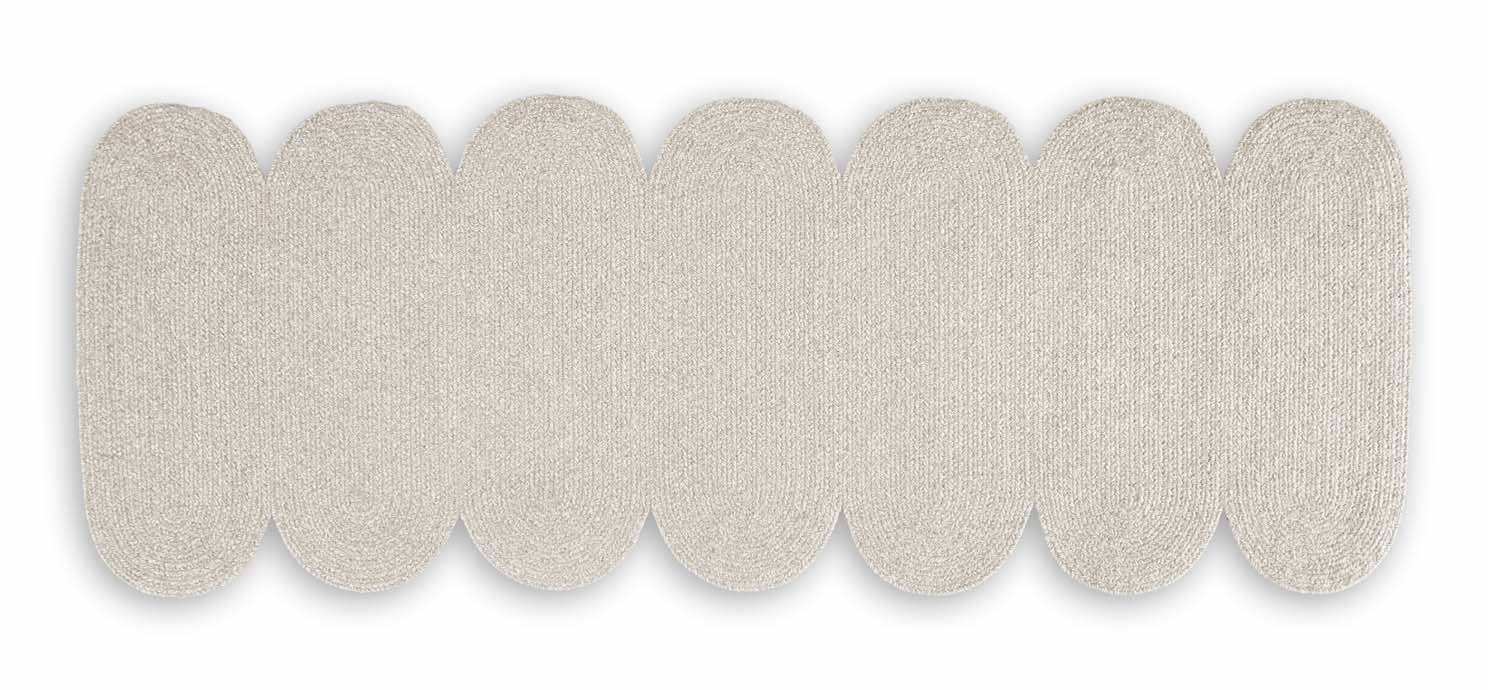

Sustainability Winner: Cicil

Rugs

Durham, North Carolina | From $169; cicilhome.com

By Lindsey Liles

The textile company Cicil has sustainability woven into its very fabric. “In the deeply personal spaces of our homes,” explains Laura Tripp, who cofounded the company with Caroline Cockerham last November, “we want to surround ourselves with things made in a way we can respect.” While most textiles are produced from either synthetics or bleached and dyed wool, Tripp and Cockerham—who met while working at eco-conscious Patagonia—instead gather wool from small family farms and co-ops in New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, including black and brown (usually considered undesirable because darker hues can’t be dyed). That wool travels to South Carolina for cleaning, or scouring, and then moves to a third-generation manufacturer in North Carolina for carding, spinning, braiding, and sewing. The final products: made-to-order, nontoxic, undyed, wiggle-your-toes-soft rugs in shades of grays and browns, sewn in curvy shapes that create as little waste as possible during production. “We have dug into every detail of our supply chain,” Cockerham says. “Love of product and sustainability go hand in hand.”

Typography by Huston Wilson

Illustrations by Alexandra Compain-Tissier