Garden & Gun Presents

Meet the Winners of the 2023 Made in the South Awards

A top-shelf American single malt, lathe-turned wooden bowls, Lone Star–inspired men’s shirts, and twenty-two other standout products that demonstrate the world-class craftsmanship and ingenuity of Southern makers

Overall & Drink Winner:

Virginia Distillery Company

Courage & Conviction PX Sherry Single Cask

Lovingston, Virginia | $150; shop.vadistillery.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Liquid Courage

A family-run distillery engineers an extraordinary Southern single malt

By Wayne Curtis

Early Scottish settlers in the South tried their best to replicate the whisky of their homeland, to little avail. But not all was lost: If the barley needed for whisky had grown easily here, explains Gareth H. Moore, the CEO of Virginia Distillery Company, “we’d never have gotten bourbon.”

Those past failures didn’t discourage Moore and his team, however. Virginia Distillery launched in 2011 with the goal of becoming a field-to-bottle producer of single malts of a quality that could compete with the best Scotch.

That drive began with George Moore, Gareth’s father. An Irish American entrepreneur, Moore found financial success in information tech in Washington, D.C. He also adored Scotch, collected single malts, and saw no reason that with the right mix of expertise, determination, and funding, he couldn’t produce a whisky that deserved a place in his collection. He sold his firm and set off to pursue that dream, living out one of his favorite sayings: You should have the courage of your convictions.

Photo: Tom Daly

CEO Gareth H. Moore.

To that end, Moore acquired farmland in central Virginia and brought in experts in distilling and whisky aging from Scotland. He commissioned a noted Scottish manufacturer of stills to craft for him gleaming copper equipment that would look at home by fen or firth. But before the distillery opened, Moore died unexpectedly, at age sixty-two. Gareth, then pursuing a career in finance, stepped forward to join his mother, Angela H. Moore, to fulfill his dad’s dream. Whereupon he learned that distilling was more complicated than one might think—and growing barley even more so. “Turns out we’re much better distillers than farmers,” says the younger Moore, who after a few disappointing harvests pivoted to procuring high-quality barley from cooler, drier climes.

And then there were cask aging and temperature. Virginia does not have the same climate as Scotland, which matters greatly when it comes to whisky. So the team worked with the late Jim Swan, who founded the Scotch Whisky Research Institute in Edinburgh. He had helped set up a noted whisky distillery in Taiwan, another place where the climate has little in common with that of Scotland. They couldn’t change Virginia’s summer temperatures, but they could alter what came out of the still to ensure it responded well to the conditions.

Photo: Tom Daly

Casks aging at Virginia Distillery Company.

Scotland has a long history of aging its whisky in barrels that formerly contained sherry, port, or other fortified wines, so Virginia Distillery followed suit, experimenting with a range of sherry casks acquired from Spain. While the contents of most of the casks were blended with other whiskies, some—like much of the whisky aged in casks that once held Pedro Ximénez sherry in Spain—tasted remarkable enough to be set aside and released as individual single cask bottlings. Some might be ready at four years; others at seven, thanks to variables such as a cask’s position in the aging warehouse (higher on the racks means hotter temperatures). In its mission statement, Virginia Distillery notes that it explores the terrain where “time-honored techniques meet new-world innovation,” yet for all that innovation, the aging of whisky remains rather mystifying, and tradition tends to top technology.

The PX Sherry Single Cask is the highest state of that art and makes for a welcome addition to the burgeoning category of American single malts. Rich and lustrous, the whisky has deep notes of figs and stewed plums, brightened with vanilla and cloves. It goes down supremely well, either neat or on ice, and is worthy of a spot of honor on any bar cart—just as George Moore envisioned.

Drink Runner-Up: Doc Brown Farm & Distillers

Butter Pecan Bourbon Cream

Senoia, Georgia | $30–$35; docbrownfarm.com

Fredrik Brodén

“If you ever ask God for patience, he’ll probably tell you to get into the bourbon business,” says Amy Brown, a cofounder, with her son Daniel Williams and friend Paige Dockweiler, of Doc Brown Farm & Distillers. The trio teamed up in 2018 to run what is now 120 acres of farmland about forty miles south of Atlanta where they grow their own heirloom corn and rye. They send the grain to Atlanta for distilling. While waiting for their straight bourbon to age to perfection (their first barrels launched this fall), they began a line of four delicious bourbon creams— think Baileys, but with a Southern accent. They extract deep, natural flavors from peppermint leaves, coffee, and cacao, which enhance their two-year-old whiskey made with Jimmy Red corn.

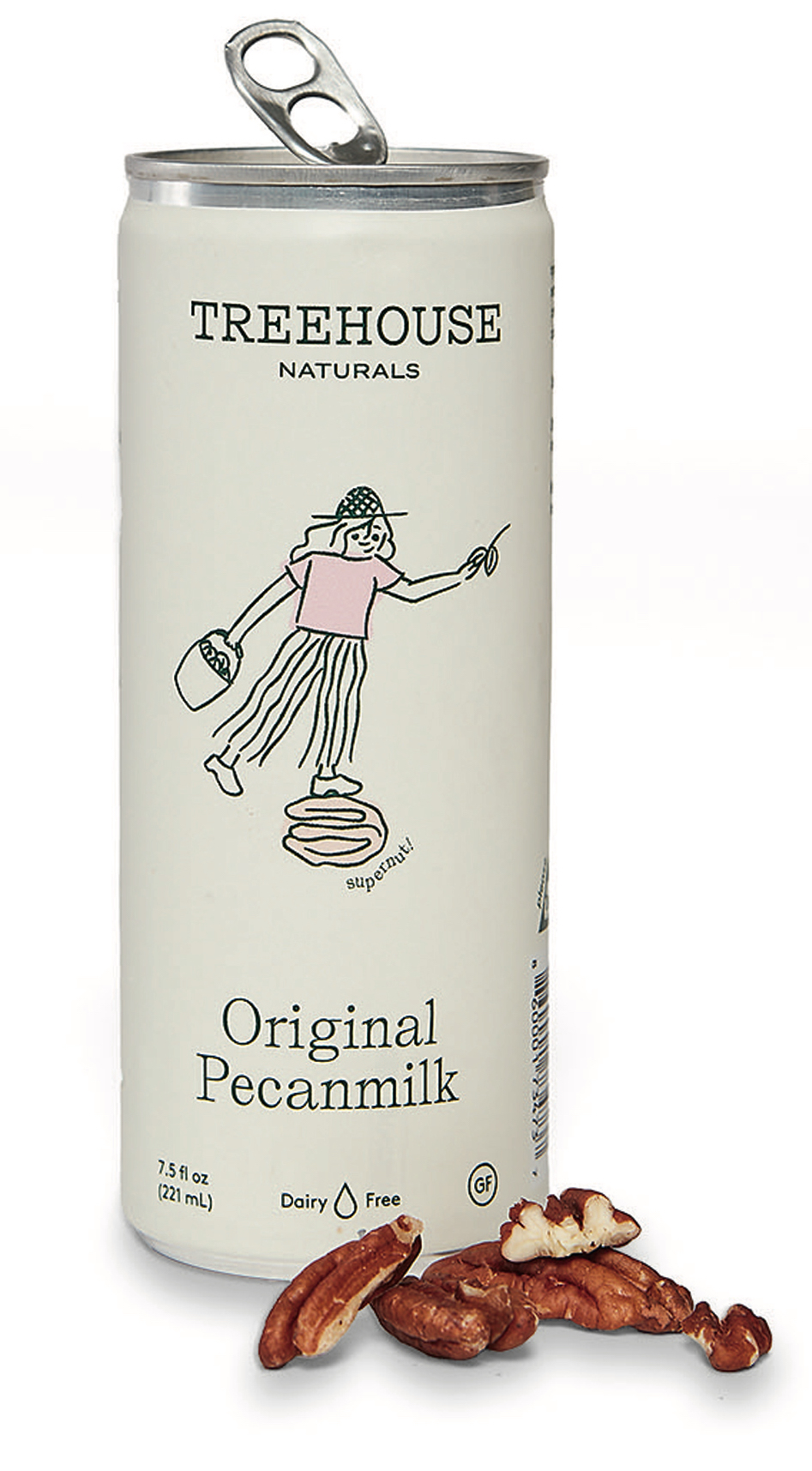

Drink Runner-Up: Treehouse Naturals

Original Pecanmilk

Atlanta, Georgia | $19–$50; treehousenaturals.com

Fredrik Brodén

“We’re on a mission to uplift pecans,” says Treehouse Naturals cofounder Bess Weyandt. In 2015, while working as a political consultant, she got to talking to Kate Carter, the wife of a colleague, and began lamenting the quality of nut milks at the time. “The only stuff on the market was filled with additives,” Weyandt says. They started making more natural versions in their kitchen Vitamixes, and a business took root. After dabbling with almonds, cashews, and other nuts, the duo settled on pecans—North America’s only native major tree nut—harvested from farms in Georgia and Texas. The milk often finds its way into cocktails and cooking, but Weyandt says fans like to keep it simple: “Most people are reporting back that they’re chugging it.”

Drink Runner-Up: Oxbow Rum Distillery

Rhum Louisiane Cane Juice Agricole

Baton Rouge, Louisiana | $40; oxbowrumdistillery.com

Fredrik Brodén

Agricole-style rum, a bright, grassy spirit made from fresh-pressed sugarcane juice (rather than the more common molasses), sprang from the French-speaking islands of the Caribbean. So it’s no surprise that it also surfaces in Louisiana, a state with both abundant sugarcane and a long French heritage. Olivia Stewart’s family has been growing and refining sugar on their farm since 1859, and in 2017, she and her team began diverting some of their sugarcane juice toward rum. They make their Rhum Louisiane Cane Juice Agricole from juice obtained within minutes of crushing at their own sugar mill, and ferment it instantly, when flavors are at their peak. As Stewart says, “It’s a real expression of Southern agriculture.”

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Hall of Frame

A former antique dealer dreams up miniature wonders

By Lindsey Liles

While trimming a two-hundred-year-old textured frame to fit an oil painting for a 2012 exhibition at his gallery–meets–antique store, Trace Mayer had a realization: The frame outshone the artwork. One of his assistants joined together the frame’s leftover corners to create a miniature quadrangle, and, inspired, Mayer added a gilded bee he had collected years earlier. “It was an aha moment that felt like fitting in the missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle,” he says. Drawing on his background in physics and fine art, Mayer played with forms and proportions to make more, gaining such a following for the collectible pieces (admirers included the late G&G contributor Julia Reed) that he began creating them full-time. Today Mayer and his team make original Museum Bees daily, using mostly circa-1860 frames or bourbon barrels to showcase an ornament that they might borrow from, say, a 1960s brooch or an heirloom belt buckle, or design themselves. “There is a level of collaboration going on,” Mayer says. “I’m reimagining an unsung artist’s work from over a century ago.” As an antidote to art-world pretensions, Mayer prices each Bee the same. “That way, the value is in the eye of the buyer, and you’ll pick the piece you love the most—the one that tells a story to you.”

Craft Runner-Up: Motyl Pottery

Wild Clay Vases

Weaverville, North Carolina | $125; motylpottery.com

Fredrik Brodén

In ceramist Tori Motyl’s work, the earth itself is the star. For a gallery show in 2019, after apprenticeships at four North Carolina studios, she put a shovel to her front yard and dug her first batch of wild clay—an experiment inspired by the storied pottery traditions of Greece, her grandparents’ home country. “I fell in love with wild clay and its beauty and grittiness right away,” Motyl says. At her Weaverville studio, she soaks red earth she’s harvested on hikes, at construction sites, or in friends’ yards in water for up to a year before dehydrating it until it’s workable. Then she sieves out pieces of sediment and throws at the wheel, or if she wants to leave in all the clay’s chunky imperfections, she molds around an armature. The finished vessels, ideal for dried or fresh flowers, feature colorful glazed bands alternating with red, rough, and unglazed wild clay. “I want people to experience how the clay looks and feels on its own,” Motyl says. “It’s straight from the ground here, where we have such a strong pottery history and community.”

Craft Runner-Up: Sea Island Forge

Grill Tools

St. Simons Island, Georgia | $80–$150 apiece; $550 for the set; seaislandforge.com

Fredrik Brodén

Steve and Sandy Schoettle always loved a night of lingering around an outdoor fire—so much so that they drew on their combined experience in construction, custom furniture, product design, and art to launch Sea Island Forge with a thirty-gallon firepit in 2014. “Spending even more time around the fire made me think, Wow, I’d love to throw a steak on there,” Steve says. A natural progression of offerings followed: a grill, a flat-iron griddle, skewers, and this set of artisan grill tools. Wrapped in a waxed canvas roll and sold as a set or individually, the spatula, sop mop for basting, tongs, and pigtail flipper are made of food-grade stainless steel that’s hammered, oxidized, and polished for an antique patina. Though each tool has thoughtful touches (the tongs are large enough to grip potatoes, the mop’s chain-mail head is a snap to clean, and the spatula has a thinned edge for easy sliding), Steve most often reaches for the pigtail flipper. “I flip everything with it,” he says. “Avocados, romaine, grilled garlic bread, you name it.”

Craft Runner-Up: Vieuxtemps Porcelain

Flower Sculptures

Greenville, Georgia | From $750; vieuxtempsporcelain.net

Fredrik Brodén

Pamela Tidwell’s hyperrealistic flower sculptures often begin with a careful study of the blossoms in her garden: foxgloves, delphiniums, English roses, poppies. “You think you know what something looks like until you try to make it,” she says. She cuts leaves out of copper and incises such intricate details as veins and caterpillar bite marks before wire cutting and soldering to make a frame. Next, the fun part: Tidwell shapes, fires, and glazes delicate porcelain blooms, each unique. “There’s a lot of measuring, standing back and looking, and, finally, just a feeling I follow.” That instinct has guided Tidwell for more than three decades; she started out making porcelain vegetables inspired by the mid-twentieth-century English artist Lady Anne Gordon, and turned to flower sculptures full-time a little more than a decade ago. Now Tidwell takes custom orders, often adding a whimsical butterfly, snail, or caterpillar to complete a plant’s look. “People put the pieces on coffee tables and mantels,” she says, “It means you always have flowers in your house.”

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Smoke Show

An old-school smokehouse resurrects a classic

By Wayne Curtis

New Braunfels Smokehouse began as quite the opposite of what it is today; when the building opened in 1943, it was an icehouse, where farmers stored their meat in lockers. Some locals decided to repurpose a structure out back into a smokehouse. When it became popular, the icehouse owners took note, and in 1945, they started smoking and selling their own products. Conveniently situated on a busy state highway, New Braunfels beckoned travelers, and soon, those visitors wanted smoked meats shipped directly to them. “Getting food by mail in the 1950s was not normal,” says Hale Snyder, a third-generation owner of the smokehouse. But stellar products and customer service won over skeptics, and a modest empire emerged. The big sellers in the 1960s included the Tastin’ Box, a trademarked assortment of meats such as Canadian bacon and “1 chub Bismarkian sausage” that eventually fell out of favor. But two years ago, New Braunfels brought the offering back, only updated. “We re-created it with some of my favorite items unique to us,” Snyder says. “Popular items, but stuff you won’t see at the grocery store.” Like cheddar jalapeño summer sausage, turkey tenders, and sweet and spicy Wagyu beef jerky, all fully cooked and ready to serve when they arrive on your doorstep.

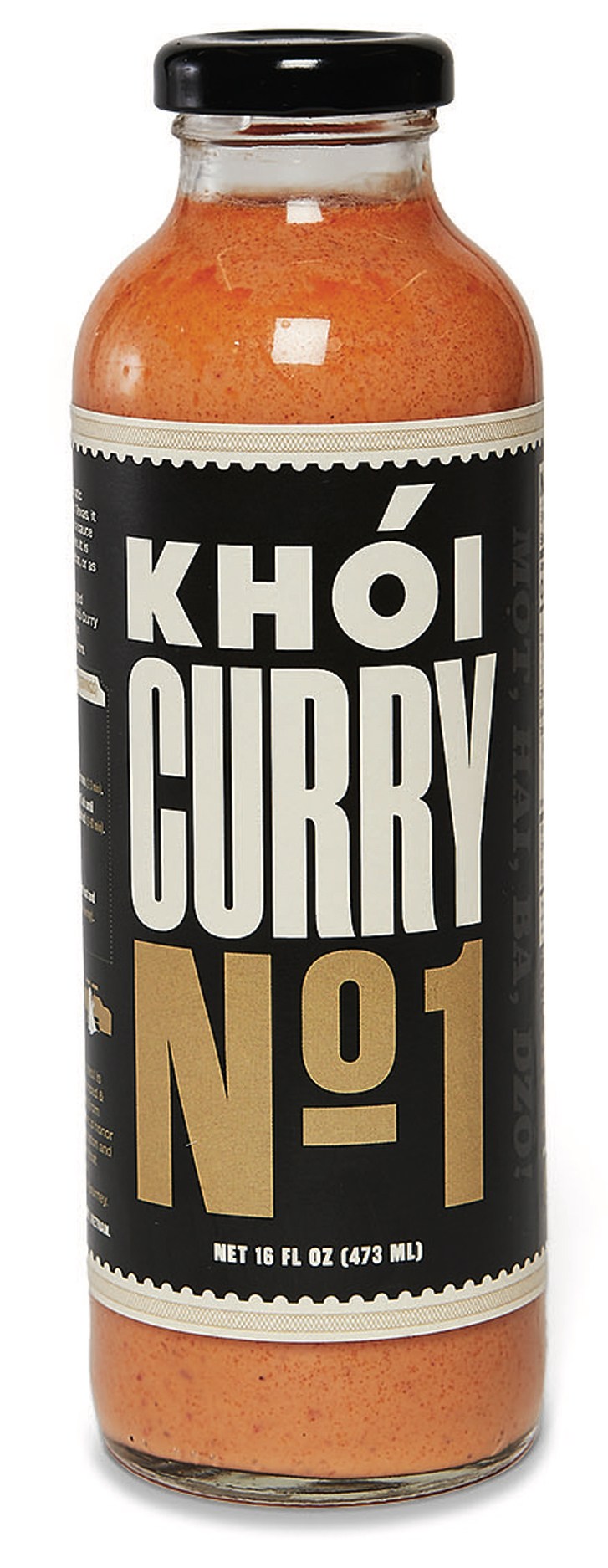

Food Runner-Up: Khói Barbecue

Khói Curry No. 1

Houston, Texas | $15; khoibarbecue.com

Fredrik Brodén

In 2017, Don Nguyen began documenting his mother’s cooking—he and his mother had immigrated from Da Nang, Vietnam, to Houston when Nguyen was five. That same year, he also acquired an offset smoker to make the smoked meats he’d come to love growing up in Texas. The two concepts collided, and he soon opened pop-ups that offered dishes like pho and smoked brisket, and beef rib curry with garlic rice. “We try to honor the Asian side, but with Texas techniques,” he says. Customers asked for his curry sauce to go, and he began bottling it under the brand name Khói—“smoke” in Vietnamese. A blend of Thai and Vietnamese flavors, it has the sensuous undertone of coconut milk layered with the brighter zing of citrus. He still sells it at his pop-ups several times each month, and he’s planning to open his own brick-and-mortar restaurant in 2024. But don’t wait until then. The sauce makes for a delicious and easy meal when served over rice with chicken or vegetables—or, naturally, smoked brisket.

Food Runner-Up: Lil’ Red’s Boiled Peanuts

Peanut Dips

San Antonio, Texas | $33 for a three-pack sampler; lilredsboiledpeanuts.com

Fredrik Brodén

About eight years ago, Michael McAndrew had a hankering for boiled peanuts. A Florida Panhandle native, he’d moved four states away and found himself disappointed. “There weren’t any in South Texas,” he says, “so I thought it would be a great idea to start a boiled peanut company.” When he offered samples, though, the texture and taste put a lot of Texans off. “They were expecting the crunch and all that,” McAndrew says. “I had to mash up boiled peanuts for Texans to enjoy.” Some customers told him these tasted like cooked beans, and that got him to thinking. He started playing around with the recipe, catering to the local palate. He added roasted red pepper for extra flavor. People liked the result. Then he created a cilantro jalapeño option (“My Texas spin on it,” he says), and then lemon dill. Folks often eat the dips like hummus—dunking vegetables or pita chips—or use them as spreads, McAndrew says: “They go well with a ham sandwich or BLT.”

Food Runner-Up: Barlow’s Foods

Peach Cobbler Syrup

Atlanta, Georgia | $9; barlowsfoods.com

Fredrik Brodén

After a decade selling medical equipment, Tiffani Neal was ready for a change. “Then one day I was making pancakes, and a friend really liked them,” she says. With the encouragement of friends and family, Neal launched a side business, named in honor of her late grandfather, Barlow Harris, a farmer and army veteran. She made pancake samples to serve at outdoor markets and at a table along Atlanta’s BeltLine Westside Trail. Passersby started to ask for syrup to go with the pancakes. “We had some peaches, so we cooked up peaches and spice,” she says, and added lemon juice and cane sugar. Customers emphatically approved, and she’s been sourcing local peaches to produce the rich, not-too-sweet concoction ever since, along with her other year-round and seasonal syrup offerings, which include strawberry bourbon, blueberry lemon, and sweet potato. “You don’t realize you’re on a journey when you’re on it,” Neal says. “But then you look back and see where you’ve been.”

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Dock and Cover

A hand-built wooden dock box makes a splash

By T. Edward Nickens

Jeff Allen grew up on Tampa Bay, fishing and water-skiing before school, then showing up to first period soaking wet. “We used every moment we could to be on the water,” he says, “fishing, diving, and skiing. It was a way of life.” Years later, when he soured on his corporate gig as a financial planner, those halcyon days proved an inspiration. He started a dock repair business in 2018, but within months Dock Appeal had transitioned to making high-end accessories for docks instead. “There’s something incredible about the nexus of water and land, how it creates such deep memories and friendships,” Allen says. “To me, docks are far more than just bridges to dry land.” The Islamorada Dock Box exemplifies that philosophy. Constructed of more than two hundred pieces of hand-worked Brazilian walnut, it gleams like fine furniture. Allen’s team planes, sands, attaches, and oils each slat by hand, and installs soft-open and easy-close hinges made from robust three-sixteenth-inch stainless steel. And maintenance, Allen says, is easy: A fifteen-minute oiling every few months will keep the dock box turning heads just as it does on day one.

Sporting Runner-Up: Weatherford Knife Company

Western Skinner Knife

Galivants Ferry, South Carolina | $250; weatherfordknifeco.com

Fredrik Brodén

When Chad Weatherford was five years old, his grandfather won an Old Timer Sharpfinger—one of the most popular knives ever made—from a country store scratch-off sweepstakes. “He had it for as long as I can remember, and I have it to this day,” says Weatherford, who used the beloved knife as the basis for the design of his Western Skinner. A former competitive archer and an avid hunter, Weatherford sought mentorship in knife making from Frank “Woody” Bridwell, a third-generation bladesmith from McClellanville, South Carolina, and has made knives full-time since 2014. This eleven-inch semicustom knife excels at deer butchering, and its sleek and stunning looks—crafted of 1095 tool steel, with a maple burl handle—don’t hurt, either. Weatherford hand cuts every blade from bar stock; shapes the handles; heat-treats, tempers, and oil quenches the steel; and freehand grinds the blade. Each knife also comes with a gorgeous, robust, hand-stitched custom leather sheath.

Sporting Runner-Up: Trollgadda Tackle and Apparel Company

Wooden Lures

Mars Hill, North Carolina | $45–$140; trollgadda.com

Fredrik Brodén

Like tail fins on a ’57 Chevy, Trollgadda lures evoke a bygone era—except these frogs will fish. In 2021, Jeff Wanat began carving and turning exquisite modern renditions of classic fish plugs to honor the memory of his late grandfather and the years the pair traveled to Ontario to cast for northern pike and lake trout. Avoiding plastic, Wanat crafts the bodies from basswood and paulownia and the scale flakes from local mica. He makes all the line ties and jointing hardware from aviation-grade stainless-steel wire and finishes the plugs with multiple coats of UV resin and paint. With its intricately painted scales and vivid colors, Wanat’s articulating Snub Nosed Crankel looks like something Tim Burton might have dreamed up, but in the water it mimics a baby bluegill, relished by bass; and the Topwater Frog, a five-and-a- half-inch segmented amphibian, gleams with red glass eyes and an almost museum-quality paint job. “I want people to go catch big fish with my lures,” Wanat says, “and pass them and their stories down.”

Sporting Runner-Up: Feather & Fin Leather Goods

Waterfowl Call Lanyards

Pfafftown, North Carolina | From $225; featherfinleathergoods.com

Fredrik Brodén

North Carolina craftsman and part-time guide Nik Faulk spent six years on the pro rodeo circuit, so he knows a bit about leather. His striking waterfowl-call lanyards can be as subtle or as eye-popping as the buyer desires, from subdued natural colors to hand-tooled and hand-painted floral and hunting motifs. More than two hundred feet of leather lace go into each lanyard, which Faulk custom dyes and seals before braiding. Some models can incorporate inlays of other materials for a true personal touch; Faulk has made call lanyards from a grandfather’s old belt and often fashions others around the collar nameplates of recently deceased dogs. “It allows folks to continue to hunt with their beloved retrievers long after they pass,” he says. “I like to create functional working heirlooms.” Faulk makes his lanyards one at a time, so customers can mix and match double-drop loops for calls, single-drop loops for whistles, remote collar attachments, and even a lip balm holder.

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Out of the Wood(s)

Soulfully crafted bowls capture Mother Nature’s beauty

By Elizabeth Hutchison Hicklin

Ben Balzer has worked with NASA, served as the CFO for a handful of California companies, and owned an internationally touted spice shop in San Francisco, but no matter what professional hat he put on, he never stopped woodworking. “I started when I was about five years old with just a little coping saw,” Balzer says. “And I’ve been filling up my garage with woodworking machines since I lived in L.A. making rockets twenty years ago.” In 2017, he finally turned his hobby into a professional gig, working in his home and studio in the North Georgia foothills, fittingly dubbed the Treehouse. “We’re surrounded by trees,” he says. “There’s no yard. Just trees.” Sometimes he’ll harvest the wood he uses to turn his simple yet stunning bowls from downed trees right there on his property, but most often, he leans on his cross-country network of loggers and woodworkers. “I’ll use any wood that is interesting to me,” Balzer says, though he has a particular fondness for the Northwestern-grown flame maple. He only requires that the wood be visually intriguing—highly figured with beautiful grain and color. He sketches, shapes, and finishes each bowl by hand using a lathe, twelve different grits of sandpaper, tung oil, and food-safe carnauba wax. The results, in Balzer’s eyes, are as much fine art as functional tools.

Home Runner-Up: Samuel Fisher Woodworker

Rocking Chair

Birmingham, Alabama | $4,500; sfwoodworker.com

Fredrik Brodén

After a decade in New York City constructing high-end cabinets and furniture for clients, wood-worker Samuel Fisher returned to his native Alabama during the pandemic to start building the furniture he’d long dreamed of crafting. “I’d always wanted to make a workbench, a crib for my daughter, and a rocking chair,” Fisher says. “All three are very complex and have to be done exactly right, or they don’t work.” And although he has fond memories of being coaxed to sleep on the front porch of his great-grandmother’s farmhouse in rural Alabama, this is definitely not his great- grandmother’s rocker. He creates the contemporary low-back design’s frame and seat to order from blocks of gleaming Eastern black walnut. The seat supports featuring locally harvested white oak—a touch of Alabama oak in every piece is a Fisher signature—help complete the floating illusion. “It feels like you’re swinging through the air,” he says of the sleek, Sam Maloof–inspired silhouette, which he polishes by hand for a silky- smooth finish and sheen.

Home Runner-Up: Rail & Stile

Modern Ming Collection

Raleigh, North Carolina | $1,800–$5,000; therailandstile.com

Fredrik Brodén

Kelly Schupp’s nine-to-five tech job was fulfilling—but not particularly creatively stimulating. “Anything related to furniture was an outlet for me,” she says. Along with her husband, Cromwell, a skilled carpenter, she began lacquering vintage furniture that had good bones but too much “life” to be considered fine. The pandemic-induced home goods boom finally enabled the duo to take their side hustle full-time. And while upcycling well-used pieces remains a cornerstone, the Schupps continued to hear the same thing from customers: “Folks loved the vintage look, but there always seemed to be something wrong with the dimensions.” Stubborn drawers annoyed, too. To address those issues, they introduced the Modern Ming collection, which includes modern-sized tables, coffee tables, credenzas, consoles, stools, and writing desks with soft-close drawers. Each antique-inspired piece is made by hand from solid American maple in the couple’s Raleigh workshop, with customizable pulls and a choice of twenty colors.

Home Runner-Up: Hartmann Fine Furniture

Lookout Mountain Field Bar

Franklin, Tennessee | $8,000; hartmannfinefurniture.com

Fredrik Brodén

“I have a degree in physics, so I gravitate toward simpler geometric forms,” says Daniel Hartmann. But minimalist design doesn’t necessarily mean modern or contemporary, the woodworker says: “The Shakers have been doing simple and unadorned for hundreds of years.” For his handsome Lookout Mountain Field Bar, though, Hartmann looked to the mobile campaign-style furniture the British army created in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Traditionally, campaign furniture is made from a tropical wood, but Hartmann favors the homegrown beauty of American walnut found around his Tennessee studio. The resulting field bar, which can hold six bottles and eight glasses, plus tools and garnishes, takes about four weeks to complete due to the intricate nature of Hartmann’s work; there are at least a dozen brass inlaid fittings, each requiring around an hour to install. And he applies all eight coats of varnish by hand. Enjoy a stogie with your drink? Hartmann can craft a custom humidor to go with it.

Style Winner: Richter Goods

Men’s Pearl Snap Shirts

San Antonio, Texas | $130–$280; richtergoods.com

Photo: Fredrik Brodén

Lone Star Swagger

A contemporary spin on classic western wear

By Elizabeth Hutchison Hicklin

“At a certain point we realized we were never going to be able to compete with manufacturing in India or China, so we decided to do the opposite,” says Bronte Treat, who runs Richter Goods, a small-batch San Antonio shirting company, with her husband, the designer Mario Guajardo, and their business partner, Carlos Echeverri. “We really believe in planting your flag and being good at one thing.” For the Richter Goods team, which includes ten highly skilled pattern makers, machinists, and seamstresses, that kind of mastery means their entire line of Western-inspired men’s shirts gets designed, cut, and sewn in-house with a hyper-focus on fit, fabric, and sustainability. To minimize waste, they keep their inventory, which is restocked weekly, intentionally low. Subtle details—pearl snaps, chevron flap pockets, and the occasional arcuate yoke—reflect the brand’s San Antonio roots without veering into camp, while natural textured fabrics, including jacquard, seersucker, denim, and lightweight linen from carefully selected heritage mills all over the world, make the collection feel contemporary and fresh. “Our customer isn’t the cowboy,” Treat says. “Every archetype of modern man is wearing our shirts.”

Style Runner-Up: Rite of Passage

Jacquard Envelop Coat

Asheville, North Carolina | $770; riteofpassageclothing.com

Fredrik Brodén

There was plenty about the American fashion industry that entrepreneur Libby O’Bryan and designer Giovanni Daina-Palermo didn’t like—notably, the loss of skilled labor to overseas jobs and a lack of sustainability. They founded Rite of Passage in 2018 to help right some of those wrongs. “We’re not interested in being a part of the problem, so we pay living wages and make high-quality garments that are going to last,” O’Bryan says of their signature pieces, including this unisex, all-season Envelop coat. They built the brand around O’Bryan’s existing partnership with the Oriole Mill in Hendersonville, North Carolina, which produced small-batch jacquards and other bespoke fabrics. When the pandemic shuttered the mill, the team relocated to Asheville’s River Arts District and began seeking out new sources for American-made fabric, which included salvaging the Envelop’s blue-tile jacquard from vintage, backstock Jhane Barnes bolts found at another closing North Carolina mill.

Style Runner-Up: Sarah Ek Muse At Studio 12

Honey Drip Collection Rings

Roanoke, Virginia | $2,750–$3,800; sarahmuse.com

Fredrik Brodén

The inspiration for Sarah Muse’s Honey Drip jewelry collection came to the Virginia artist, designer, and goldsmith in a vision—literally. During her daily meditation practice, the bright golden drip, which she says represents heightened perception or the opening of one’s third eye, appeared. “It just called to me,” Muse says. “I had to act on it. I went to the studio and started carving and I couldn’t stop.” The ethereal capsule collection includes four elegant ring designs plus two pendants, and she plans to add a matching bracelet and earrings. Inside her studio, tucked into the Blue Ridge Mountains in Roanoke, Muse hand carves each Honey Drip ring from wax before sending the molds to a casting company, which casts them in solid eighteen-karat gold and then returns them to her for a final polish and brush finish. The statement rings are substantial enough to be worn on their own, but Muse loves how their asymmetry allows a wearer to artfully stack them together.

Style Runner-Up: State the Label

Hand-Painted House Dress

Athens, Georgia | $250; statethelabel.com

Fredrik Brodén

Textile surface design—marbling, dying, airbrushing, screen printing, stamping, painting—brings an element of fine art to STATE the Label’s collection of handsewn swimsuits, pants, blouses, accessories, and dresses, including the brand’s beloved House Dress. “The cut is simple and timeless and classic,” says STATE’s designer and co-owner, Adrienne Antonson, of the silhouette. “It’s flattering on all sizes. And it’s a really great canvas for what we do best: hand painting.” Like many of STATE’s one-of-a-kind looks, the cotton House Dress embraces versatility; the wearer can dress it up for dinner, cinch a jacket around the waist for a tighter fit, or toss it on over a bathing suit. For the all-female design team, sustainability means just as much as creativity, adaptability, and style, so they emphasize natural fibers as well as recycling and reuse throughout the production process. “Our cutting department saves every little shred,” Antonson says. “We keep inventing new ways to use the scraps.”

Sustainability Winner: Yaupon Brothers American Tea Co.

Lavender Coconut Yaupon Holly Tea

Edgewater, Florida | From $10; yauponbrothers.com

Fredrik Brodén

Exactly one plant native to North America has caffeine: yaupon holly, an evergreen shrub consumed by Indigenous people for millennia. “The United States imports a quarter million tons of tea a year so we can dunk a bag in hot water for five minutes and throw it in the trash,” says Bryon White, who cofounded Yaupon Brothers American Tea Co. in 2012 with his brother to spark the plant’s comeback. “Why not build a supply chain around a plant that’s uniquely ours?” The Whites have done just that: Each leaf is handpicked on organic farms in Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama; dried, roasted, and ground at their facility in Edgewater, Florida; and then packaged into compostable tea bags. “Yaupon has been used by humans for almost ten thousand years,” White says. “And it’s now time for it to come back to mainstream culture.”

Illustrations by Michael Hoeweler