Arts & Culture

President Lincoln’s Cottage: The Quietly Powerful D.C. Museum You Might Not Have Heard Of

With a simple walnut desk and stories to fill volumes, President Lincoln’s retreat is a heartbreaking time capsule of American history

Photo: Briann Rimm, courtesy of President Lincoln’s Cottage

President Lincoln’s Cottage in Northwest Washington, D.C.

About three miles from the White House, along snaking roads older than the capital itself, on a hilltop overlooking the city of Washington, D.C. in a rambling cottage with gingerbread trim, you’ll find the bedroom where Abraham Lincoln composed the Emancipation Proclamation.

There’s not much to the room, actually: The floors are hard pine, the door includes mullions and inset panels that demonstrate fine hand-craftsmanship, and tall scalloped baseboards rim the room. The windows feature wooden louvers of a nineteenth-century design, used to mute the sun that illuminates the room most of the year.

There is no furniture in the bedroom, except for a desk. It’s a simple thing of dark walnut, its unadorned stowaway writing surface displayed in the open position. Lincoln wrote bits and phrases of the Proclamation on small pieces of paper and kept them in his hat. He would then sit at the desk in the cottage and stitch them into drafts. They are now kept in the Library of Congress.

President Lincoln’s Cottage, while relatively obscure, is among the most consequential presidential sites in the nation’s capital. It’s where Lincoln and his wife, Mary, spent nearly a quarter of his presidency, from May to November of 1862, 1863, and 1864. It’s where they escaped downtown Washington’s stinking, malarial summers. The Lincolns retreated to the cottage in grief after the death, by typhoid fever, of their eleven-year-old son Willie. They were at the cottage on April 13, 1865, the day before they went to see Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater.

Photo: Briann Rimm, courtesy of President Lincoln’s Cottage

A bronze statue of Lincoln stands outside the cottage.

The cottage was never intended to be a presidential retreat. It was built in 1842, in Gothic Revival style, by banker George W. Riggs. The federal government bought it from Riggs in 1851—using booty paid by Mexico City to spare itself from attack during the Mexican War—to build a home for disabled soldiers.

By the time the Lincolns moved in, 132 wounded veterans lived in the Soldiers’ Home, in newly constructed buildings not far from the cottage. On summer nights Lincoln would chat with the men, many of them missing limbs, who reported what it was like to fight the war he presided over. On the other side of the cottage lay the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery, the nation’s first military burial ground, where the Civil War dead were put to rest in rows of gravestones that ripple along the rises and hollows. Lincoln heard taps being played daily.

Photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

An illustrated lithograph of the Soldiers’ Home from 1863.

Lincoln might not have spent so much time at the cottage if it hadn’t been for the death of Willie in February 1862, likely from contaminated water at the White House. He was the second of the Lincolns’ children to die. Lincoln was stricken, Mary inconsolable. She described the White House as a “tomb.”

“When we are in sorrow,” she wrote, “quiet is very necessary to us.” And so she and the president decamped for the cottage. Carriage-loads of supplies and equipment were hauled there so the nation’s work could continue.

The tour of the cottage, a National Monument and a National Historic Landmark, is low-key and low-tech. A docent guides visitors through the rooms, telling stories and pointing out details, like recently discovered decorative painting on the walls that has been painstakingly revived. A highlight is the furnished salon where Lincoln entertained, often with annoyance, the many office-seekers and blowhards who managed to track him down for an audience.

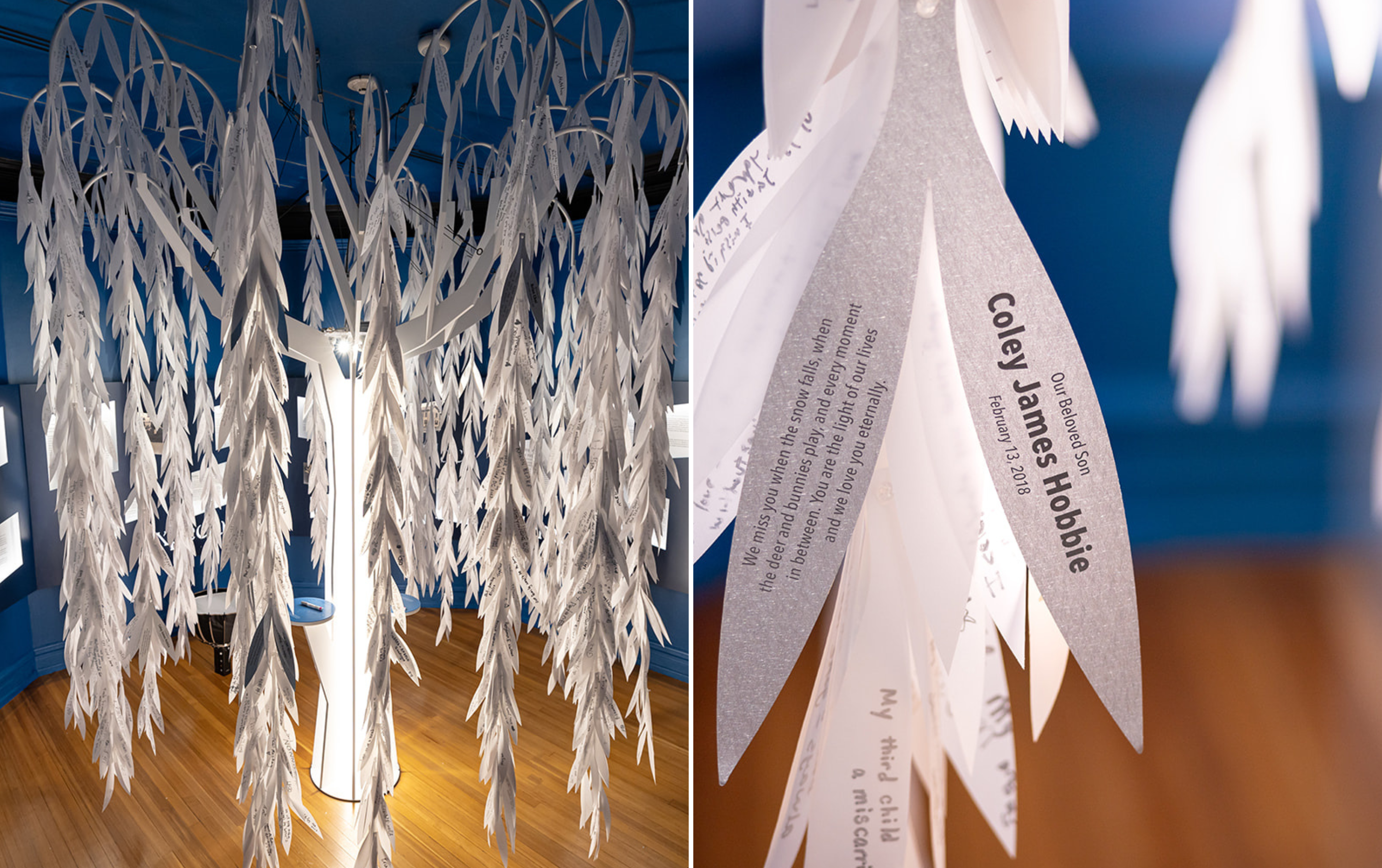

But a display on the first floor of the visitors center may be what you remember most. Reflections on Grief and Child Loss is a tribute to all families who, like the Lincolns, have lost a child. In the center of the room stands a white sculpture of a willow tree, its limbs heavy with hundreds of individual leaves bearing parents’ messages to their dead children.

Photo: Briann Rimm, courtesy of President Lincoln’s Cottage

Reflections on Grief and Child Loss, an exhibit that connects the Lincolns' loss to present-day families who have experienced grief after losing their own children.

“We miss you when the snow falls, when the deer and bunnies play, and every moment in between,” reads the note to Coley James Hobbie. As it happens, the note was written by Cottage CEO Callie Hawkins, who had worked for the site for years in 2018 when Coley was due, on February 12, Lincoln’s birthday. He was stillborn the next day.

Reservations are required at President Lincoln’s Cottage. For more information, visit lincolncottage.org.