Artists

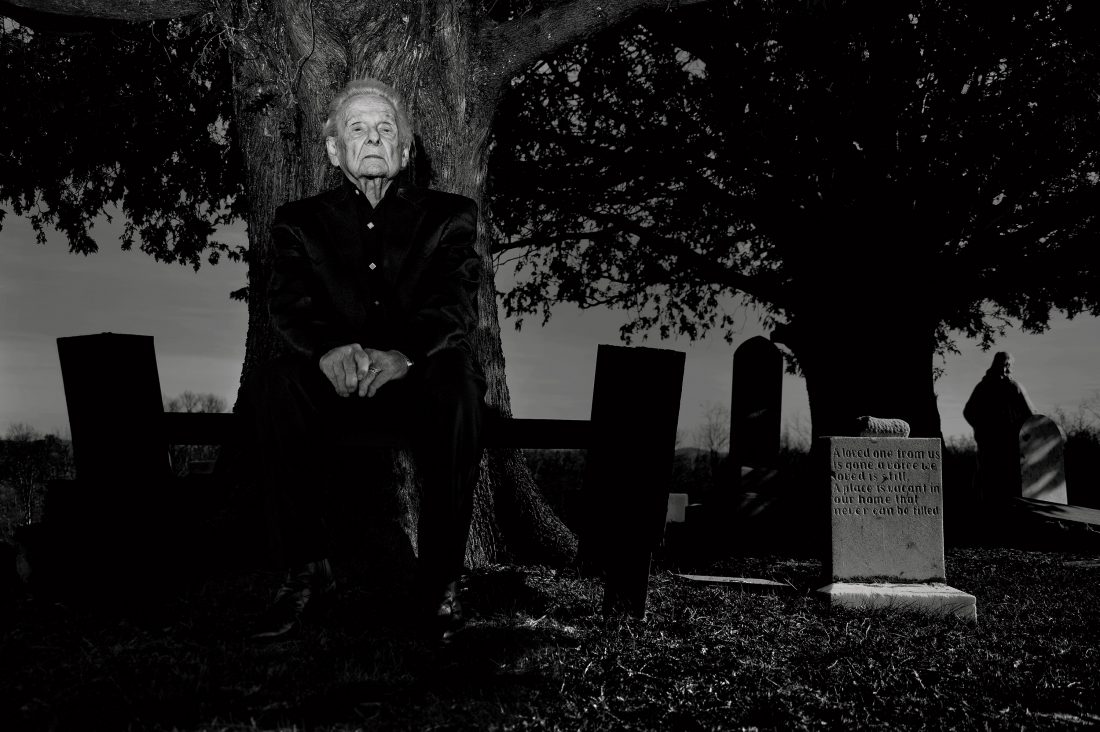

Ralph Stanley: Long Road to the Mountaintop

Photo: Jim Herrington

The ridges are so high and steep where Ralph Stanley hails from, an old saw has it, that if you drove off the top of one you’d die of starvation before you hit bottom. One winter when he was a boy, there in the coal country of far-southwestern Virginia, the family milk cow’s tail froze off. They had no electricity, no indoor plumbing. Ralph and his brother, Carter, didn’t have to walk a mile to school—it was more than two, hoofing it through the woods at dawn and returning home after dark. Even before their father left them, chores started at 3:00 a.m. If anyone ever had a legitimate claim to singing mournful Appalachian ballads born out of hardship, it’s Ralph Stanley.

The long days had their advantages, though, if you were going to play hooky at your uncle’s, say, to make moonshine. The income came in handy. To get around in these parts, Ralph bought his first mule when he was fourteen, for thirty-five dollars. And from these hardscrabble roots something else also sprouted. Ralph and Carter played the banjo and guitar, respectively, and sang—Carter in the lead, Ralph harmonizing—at the mining camps on payday.

What began at those camp sessions took Ralph Stanley farther than he ever dreamed. His tours have brought him to all fifty states—he’s played Carnegie Hall, Ryman Auditorium, Austin City Limits— and as far from Dickenson County as Japan, where a fan club and packed houses testify to his influence. But in a sense he’s never left these mountains, where he started out and will forever remain. This Memorial Day, he will hold his forty-third annual bluegrass festival in the natural amphitheater beside the final resting place of his mother and brother, in the family’s Hills of Home Cemetery, crowned by two enormous cedars and overlooking miles of hollows and ridges stretching toward Kentucky.

Photo: Jim Herrington

Hands of Time

Stanley has played everywhere from coal mining camps to gin joints to Carnegie Hall. “You can tell my banjo picking from anybody else’s,” he says. “To my notion, it’s got a keener sound to it.”

Stanley is eighty-five now, and he has put out some two hundred albums. His high lonesome tenor, exuding world-weariness, has been called “one of the most expressive voices in the history of American song.” It’s also one of the most recorded. Should a sculptor ever decide to carve a Mount Rushmore of bluegrass, Stanley will be a shoo-in. But mainstream celebrity did not come to him until he was in his seventies, following the release of the Coen brothers’ Depression-era, Odyssey-inspired movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? in 2000. The film’s inspired sound track, produced by T Bone Burnett, went multiplatinum, and Stanley’s solo a cappella rendition of the traditional Appalachian lament “O Death” stole the show, winning him a Grammy for best male country vocal performance.

Oh death please consider my age

Please don’t take me at this stage

My wealth is all at your command

If you will move your icy hand

“I never expected it,” Stanley says of the award. “I’m just thankful I got it.” This, I learn when I visit his Virginia home, is about as effusive and egotistical an utterance as you’re ever likely to hear from him.

Stanley was raised on Smith Ridge, the home of his mother’s people. He has ensconced his extended family in a jumble of houses near the “old home place,” which he has preserved as it was when his mother, Lucy Smith Stanley, lived there, raising him and Carter by herself after her husband left, feeding them rashers of home-cured bacon cooked on a wood fire.

I make the trip there with Jack Hinshelwood, executive director of the Crooked Road, a tourist trail through Virginia’s southwestern hill-music country (anchored, in part, by the Ralph Stanley Museum and Traditional Mountain Music Center in Clintwood), and Joe Wilson, a longtime folk music promoter. I follow them from the town of Coeburn, and after an hour of twisting and turning on narrow Clinch Mountain roads, we arrive on the mountaintop.

We park behind Stanley’s sprawling yellow-brick ranch house next to Big Blue, a custom-outfitted, two-tone steel-and-teal tour bus. The bus has logged more than a million miles over the last decade, although in recent years Stanley has eased back on the throttle, trimming a schedule of 200 gigs a year to around 120. A trio of dogs greet us with Hee Haw shrugs and put their heads back down.

Photo: Jim Herrington

Out of the Shadows

Stanley’s songs have earned him a “Living Legend” medal from the Library of Congress, induction into the Grand Ole Opry, and an honorary doctorate of music.

Stanley, fastidiously dressed in dark pants and a purple cowboy shirt with gold stitching, his signature silver hair brushed back, welcomes us and leads us into the kitchen. As we settle in on stools and chairs, his wife of forty-four years, Jimmi, strolls in wearing a bathrobe. “Sorry, I didn’t know you were here,” she says, apparently only mildly surprised to find three visitors in her kitchen, hanging on her husband’s every word. “I was going to wash my hair.”

Stanley was shy and reclusive growing up, but he is friendly and observant and has a twinkle in his eye. His mother—one of twelve Smith children, all banjo pickers—taught him to play in traditional clawhammer style, and the quiet boy came alive when he could hide behind a banjo. He would later learn to pick the more contemporary and rapid three-finger style. “I have a three-finger lick like all banjo players do,” he explains, “but you can tell the difference, a little different roll. Earl Scruggs was the first I listened to.” Scruggs himself, in fact, gave him some pointers. Stanley’s playing is tied to his singing. “If I put a slur in a word, I put it into my banjo the same way,” he elaborated in his 2009 autobiography, Man of Constant Sorrow (named after an old Stanley Brothers hit revived by the O, Brother sound track). “They’s both proper instruments, the voice and the banjo. I try to make my banjo sound as much like the sound of the words as I can.”

At that, Stanley’s twenty-year-old grandson, Nathan, comes in and joins us in the kitchen. With dark sideburns and hefty-Elvis looks, Nathan is now the lead singer and mainstay of the Clinch Mountain Boys, the band formed long ago to accompany the Stanley Brothers. “He taught me how to be a straight arrow,” he says, nodding at his grandfather, “how to be a good upstanding young man.” He also taught him a thing or two about music. Nathan first appeared onstage at the Grand Ole Opry in 1994, when he was two. “He’s kept it pure,” he says of his grandfather. “He’s kept it traditional. A lot of artists go with the flow. He’s never changed.” Nathan sees it as his job to keep his grandfather’s style of banjo playing going. “That style is rare,” he says. “It’s so simple, it’s hard. You almost have to be born with it.”

To this day, Ralph is disinclined to talk about himself much. Jimmi calls him Poker Face. When I ask if he has a favorite album, he says, “I like ’em all; I’ve done my best on all of ’em. And done ’em as natural as you can. No put-on.” Summing up his seven-decade career, he simply says, “Just tried to get better all the time. Never practiced much.”

Then he deadpans, “Might have been a bad mistake. I might have been good if I’d practiced.”

Nearly every old-timey musician has a hard-luck story, or demons. Doc Watson was blind and lost his son, Merle, in a tractor accident. Bill Monroe lost both parents before he was twenty, nearly died in a car wreck, and at least once had to duck a Bible hurled onstage at him by an irate woman. (I was there.) Carter Stanley, Ralph’s older brother, drank himself to death in his prime.

In their twenty years of touring together, Carter sang lead and cracked jokes. He was inevitably the life of the party—“a gregarious, handsome, back-slapping charmer,” as a writer once described him. Ralph had the more unusual voice, which made for rich harmonies and a haunting mountain sound. “Carter and me, when we were little boys, heard people on the radio and in church,” Stanley says. “Bill Monroe was my favorite singer. I liked his voice and the way he phrases.”

In 1946, after serving in World War II, Ralph and Carter formed the Stanley Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Boys and took local radio by storm. Based in Bristol, Virginia, they loaded up the band and all their instruments in a hulking ’37 Chevy—later a ’39 Cadillac, then a Buick, then a Packard—on incessant tours, performing at drive-in movie theaters, high school gyms, county fairs, union halls, honky-tonks, and town halls. Life on the road was rarely dull. In Pikeville, Kentucky, in the heart of Hatfield and McCoy country, a show was canceled after one bootlegger unloaded his pistol into another on the dance floor.

Starting in 1948, the Stanley Brothers recorded for the major labels Columbia and Mercury, and that and their relentless touring led to exposure beyond the hills and hollows. Their hits ranged from the banjo instrumental “Shout Little Lulie” to the moonshine ode

“Mountain Dew” to the gospel “Angel Band.” Stanley still sings the ballads “Pretty Polly” and “Man of Constant Sorrow” at every show. The brothers, especially Ralph, resisted bending to country music fads. Once, when Carter suggested the radical idea of adding a Dobro to the mix, he threatened to quit.

Everywhere they went, people wanted to drink with Carter, and Carter never let them down. While touring near the end of his life, the band would pull over onto the side of the road so that he could heave blood. He died in 1966. At his funeral, in a packed high school gym, Bill Monroe sang “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” a cappella.

Afterward, Ralph, who had always stood in his brother’s shadow, who made sure bills were paid and the car had gas, was devastated. He credits faith and family for keeping him going, and slowly, he learned to take the spotlight while sticking close to his musical roots. He insisted on singing gospel songs at every gig, even at roughneck saloons, at one of which the owner unplugged his amps, igniting a brawl.

Unflagging, Stanley went on to nurse the next generation of bluegrass and country standouts. He hired Larry Sparks, and later Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley, to join the Clinch Mountain Boys. More recently, Ralph and Jimmi’s son, Ralph Stanley II, whose voice and guitar chops hark back to his uncle Carter, played for the band and then went solo, earning Grammy nominations of his own.

Before we leave, Stanley breaks out his banjo and plays us some tunes, first in the old drop-thumb clawhammer style, using the backs of his fingernails, then with picks. Slowed by arthritis, he doesn’t play as much anymore, but he still loves to sing. “I do just a little clawhammer now and then,” he says. “If I don’t have the banjo to think about, I can put more into my singing.” With the burnish of age, his voice is, if anything, more moving, more haunting, more mournful than ever.

Oh death, Oh death

Won’t you spare me over ’til another year

Well, what is this that I can’t see

With ice cold hands taking hold of me

“I sing it the way I feel it,” he says. “No put-on to it. I just sing, and it’s lonesome.”