Arts & Culture

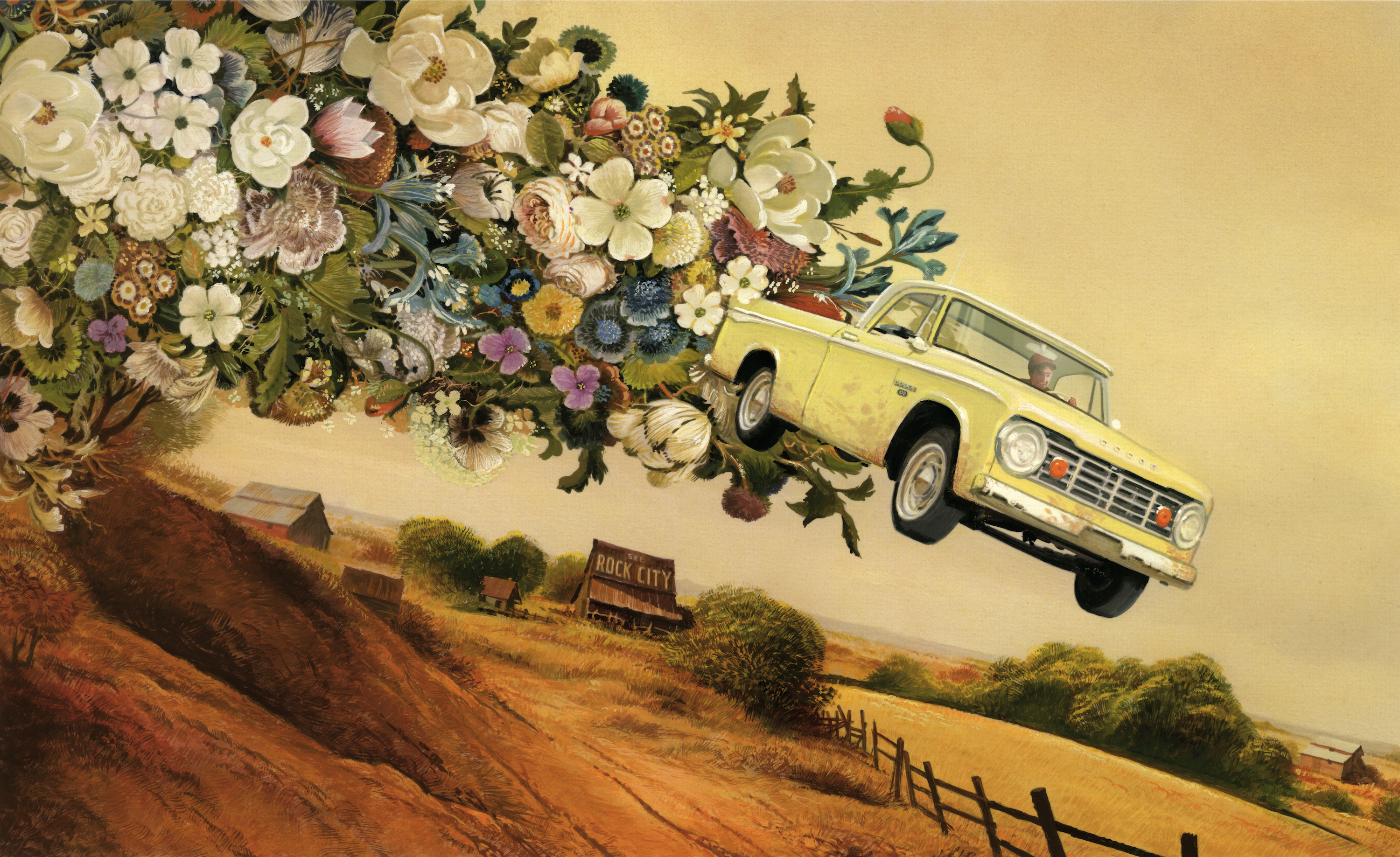

Rick Bragg’s Truck Love

The writer logs the mileage of his life in trucks—rickety hunks of junk, sleek dual cabs, and every kind of pickup in between

Illustration: Bill Mayer

I like green most of the time—deep green, emerald green, British racing green—but this was just wrong, tragic, as if some stoned autoworker on a long-ago Detroit assembly line painted it that color on a bet.

“Do it, Hubbard. Do it. I dare you.”

Squirt-squirt-squirt…

“Ohhhhh, man! I didn’t think you’d really do it.”

It could make you queasy just looking at it, the only pickup in Calhoun County, Alabama, that no one—not even the most shiftless of men—wanted to lean on, in case that paint job would rub off and spread like science fiction.

It was an impulse buy, as I recall. I traded a silver ’74 Firebird for it, but only after two nitwit teenagers—befuddled on Boone’s Farm and bereft of insurance—sideswiped me on a rainy night in ’79. There is nothing sadder than a beautiful car all beat to hell, and I couldn’t afford to fix it. The pickup was ugly, yes, but it was honest about it; it wasn’t puttin’ on airs. At least, I remember thinking, it was probably mechanically sound.

It was not. It needed shocks and a new front end, which would not have mattered if I lived in a state with smoother roads. But Alabama is not famous for its infrastructure; at one time, as I remember, about two dozen elected officials were indicted for taking kickbacks on concrete pipe. All I know is, every time I drove off the lip of a pothole, it felt like I was driving off a cliff, and it hit so hard at the bottom I would momentarily lose control and find myself, on the bounce, in the path of oncoming cars.

“Want to ride with me to town?” I asked my little brother, Mark, one day.

“In that?” he asked.

He swears, even today, that the Dodge cracked at least one tooth. I learned, by painful experience, not to clench my teeth when I hit a rough spot, but I still managed, a dozen times, to almost bite off my tongue. The pothole violence jolted the wires off the plugs and cracked the distributor cap, so it ran rough when it ran at all, and rattled like a bag of marbles in a galvanized coffeepot. The heater didn’t work. The radio didn’t work; didn’t even hiss. The seats seemed to have been stitched from asbestos and cat hair. It rolled on four bald tires, purchased, at five dollars apiece, from a man named Houston Jenkins; they should have cost more, but I guess he felt sorry for me.

It was, ecologically, a rolling Superfund site. It smoked, leaked oil, ran hot, and spewed antifreeze, and I carried a case of oil and gallon jugs of water in the front floorboard. I spent long hours staring under its hood on the side of some desolate, godforsaken highway. Which is exactly what you want to do when you have the ugliest vehicle on earth. You want to be seen with it.

I can’t remember what happened to it; odd, that I can’t. I do recall that as soon as I took possession of it, I put a Briggs & Stratton lawn mower in the back to take to the repair shop. Two years later it was still there, still unrepaired, still bucking with me over those ruts. It was still back there the day I drove the truck to the Weaver First United Methodist Church to get married the first time.

It was not a good truck, but I miss it, sometimes, because it was part of me, and the best I could do at the time. I think trucks are like that down here, not just a way to get from one place to another—which is never a sure thing, in a Dodge—but a kind of rolling, bouncing box to hold our stories. We even name them. In my family, there was Red, Old Red, Little Red, Blue, Big Blue, Little Boy, Norman, and a ’63 Chevrolet we called Cadillac, I guess to be ironic, though I don’t think we knew what that was back then. But in every crumpled fender and crease of rust, there was a story, the history of a stiff-necked people. We knew our trucks had about the same fuel economy as a 747 and wouldn’t fit in a Birmingham parking garage on a bet, but we could haul eight hundred pounds of fertilizer, a half ton of cement block, a dollhouse, or a live alligator. I just know that, in the South, the pickup truck is the chariot of our people, rich and poor, old and young, Black and white, and there ain’t no romance in an SUV, is there?

My big brother, Sam, passed away last year. I miss him more than I can say, miss his wisdom. He explained to me once that life was just better in a truck; or, maybe, the world just looked better.

“You’re up high,” he told me as we walked through a car lot one Sunday afternoon, just looking. “You see everything in a truck.” You see farther down the road, he said, and deeper into the woods.

“People wave at you, in a truck,” he said, “’cause they can see you better.” He made the windshield sound like some kind of magic mirror. I told him I doubted if people would be any friendlier just because I was in a truck, and he told me, well, yeah, you may be right.

I bought a new pickup recently, a dove-gray 4×4, and took a long ride through the mountains of North Alabama. No one will know it’s me, in this new truck, I remember thinking. But everyone waved.

Well, I’ll be damned…

Illustration: Bill Mayer

The floorboards were so rusted my mother can remember looking down when she was a girl and seeing the red dirt passing underneath, so fast that, surely, they would drive off the edge of the world.

“The fartherest we ever went was to town,” she said, so she reckoned the end of the world was somewhere beyond that. Either way, there was nowhere on this planet, she believed then, you couldn’t go in a flatbed Ford.

My mother’s people were movers. The old-money people rolled their eyes when they saw their old truck go by, sagging with everything they owned. My people never owned any dirt of their own, no place to sink roots. My grandfather made liquor in the mountains and swung a hammer when he could find the work, and a man like that, in the Great Depression, had to keep moving to survive. Usually it was on the day the rent came due. He made his first truck from a Ford Model A, using a blowtorch and a hacksaw to cut the rear off the car and replace it with a wooden bed. And about once a month, he loaded up his wife, seven children, kitchen table, hog, chickens, dogs, mattresses, rocking chairs, and everything else they owned onto that homemade truck and moved—a whole life in one trip, or two—through dusty main streets and down pulpwood trails. You can’t move a whole life in a car, unless you are willing to leave part of it behind.

“We come back for the cow,” my mother said, “and the horse.” She cannot recall the name of the truck, or the cow. “But the horse’s name was Bob,” she said.

Once, during an attempt to load a five-hundred-pound hog, the creature got a running start and hit the steel bumper headfirst, keeled over, and died. The whole family stood around, stunned.

“Suicided itself, by God,” my grandma said.

Still, my mother never sees a truck loaded with beds or Barcaloungers or Frigidaires that she does not think of her daddy, and her great family, and spareribs.

* * *

The first truck I ever drove was my uncle’s dark blue ’67 GMC, which only looked blue in the aftermath of a thunderstorm. Red dust shrouded it most of the other time, like a second coat of paint.

It was the seventies, and in the summer I worked on his crew. We did bulldozer work, cutting roads and knocking down trees. I always drove the pickup to the jobsite, mostly because my kin thought my chances of killing anyone in it were less likely than in one of the giant dump trucks.

Time froze, in that truck. It had the same empty can of brake fluid rolling around in its bed for seven years, the same six-foot length of logging chain going to rust, the same Poulan chain saw in the passenger floorboard. The cab always smelled like oil, gasoline, and Winstons. I would wonder, when I was a boy, if one day my uncle would snap open his chrome Zippo lighter and—BOOM—smoke us all straight to hell.

I ran a saw and swung a pick and hand-loaded sticks of pulpwood on a flatbed dump, but mostly—because I was supposed to be the smart one—I was in charge of lunch. I collected money and headed for the nearest fast food, elbow out the window, singing the Eagles at the top of my lungs: “It’s a girl, my Lord, in a flatbed Ford / Slowin’ down to take a look at me.”

I came back with sacks of hamburgers and cardboard caddies of ice-cold RC Cola, but, somehow, never as many french fries as there should have been. The crew gathered around for their change, and we sat in the dirt and ate and talked about good dogs and mean women, and snakes. They were all good to me, looked out for me, and now they are all gone.

I would like to tell them it was me that ate all those fries, but I reckon they knew, reckon they thought it was my commission. At the end of the day, wore slap out, we would crawl into the cabs of the trucks and head home, but the GMC—we called it Blueboy—had a three-on-the-tree, and the gears always hung up on me in the middle of town. I would get out and raise the hood and work the linkage free, careful not to let it mash my fingers, and I would wonder if the people passing by sneered at me because I was so sweat stained and begrimed.

Now, after all this time, I know I was in the best of company, squatting in that dirt, working on that old truck, just another mover in a long line of movers. And I know what they have always known: that you can’t carry much of anything with you that’s worth a damn in a little-bitty car.

The GMC fell to rust and ruin.

The grass grows over the men I worked beside.

And I am moving, still.

Illustration: Bill Mayer

New trucks are different somehow, or maybe I am just so old I distrust anything that is still shiny, that rolls without a limp.

GMC now offers a tailgate that flips fourteen different ways. They ought to be ashamed of themselves. I thought a tailgate was intended to keep things from falling out. GMC says it is a good place to rest your laptop. Kill me now.

Ford makes a truck called the Platinum. It is very, very shiny. If I had driven a truck called the Platinum, I am fairly positive that someone would have kicked my ass.

They have trucks now that, they say, can light up a whole house, trucks with movie screens in the back seat for unruly children. I just can’t imagine gathering around them, in the glow of the GPS, to talk for three hours about the weather.

Dodge seems to be very popular now, to be taking over the world. I watch their television ads and start to nod along, and then I come to my senses. What the hell was I thinking? At least they seem to have abandoned the avocado color scheme.

They sell new trucks now that get jacked up into the heavens—at the factory. In the old days, you had to really have redneck in you to jack a truck that high. They dress them up with wheels that look like they were wrenched off the Batmobile, or a spaceship—at the factory.

The people who drive them don’t need to know where they are going, or where they’ve been. The GPS talks to them. It does not have a Southern accent.

I guess I’m as bad as everyone else. I tried to find the most honest truck I could, a gray Tundra 4×4, with stock steel wheels that can take a lick when I have to bounce across a creek or through the pasture. I haul ready-mix, gravel, and hog feed, and diesel fuel for burning brush in the pasture. I take my mother to the doctor, and my little brother to the parts store.

Sometimes I wait for him in the truck, and people walk by and stare.

“Nice truck,” they say.

“’Preciate it,” I say.

But what I am thinking is: You’re damn skippy, it is.

I can get Buck Owens on the SiriusXM radio.

A good friend of mine, who has owned a few dozen pickups himself, crawled into the cab recently and whistled.

“This is the last one you’ll ever need. It’ll take you on out of here.”

I reckon so.

* * *

I do have one good memory of that old green Dodge. I was running late for a date. We were going to the Shoney’s for a hot fudge cake. I had some pretty serious hair back then, blond, spun gold, and it was still wet when I jumped in the old truck.

I hit a smooth patch of asphalt on Highway 21, and I hung my head out the driver’s side window to dry my hair. And as the hot wind flowed past my face, I guess I was as free as I have ever been.

Take it easy, take it easy

Don’t let the sound of your own wheels drive you crazy.