Food & Drink

Southern Chefs Go Hog Wild

Invasive feral pigs wreak havoc on native landscapes—but as many Southern hunters know, they sure can shine on the plate. These five myth-busting recipes, from a Louisiana pork chop to a spring Bolognese, provide ample inspiration to stay high on the hog

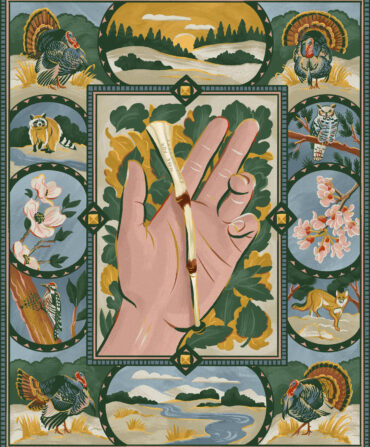

Photo: Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

A wild-hog country ham from Auburn, Alabama, chef David Bancroft.

In at least one respect, it’s a pity we aren’t French. If we were, few would sneer, or snort, or wrinkle their noses and push back from the table when presented with a serving of rich, cognac-colored daube de sanglier. But place a crock of wild-hog stew on most American tables and that grating sound you hear might be chair legs scraping hardwood.

That’s changing, and in ways that should delight hunters, cooks, and others who have embarked on this most postmodern of culinary journeys: the path to loving the wild hog. That feral hogs are an overpopulated blight on the South and beyond is undisputed. That they have an emerging place in both restaurant and home kitchens is an increasingly accepted truth. Rich and robust, wild hog meat can span the flavor spectrum, from sweet to earthy, as the animals tend to take on the terroir of their environs, be they acorn-rich hardwood ridges and bottoms or cornfields bordered by wild swamp. And the fact that they root up and wreck both wild and cultivated landscapes puts them at odds with those trying to conserve fragile wetlands and plots of heritage vegetables alike.

“They are a morally unambiguous animal to hunt, and I love hunting for them just about anywhere,” says Jesse Griffiths, an Austin, Texas, chef whose hunting and butchering classes—and cookbooks, including his forthcoming The Hog Book—have changed many minds about wild game. “They are invasive and destructive, and by hunting wild hogs, you feel that you are accomplishing an ecologically good deed. And they’re actually delicious. But there is so much misinformation and myth about cooking wild hogs.”

And therein lies the problem: A wild hog comes with only two hams, but a lot of buts. But they’re tough. But they’re gamy. But they’re hard to cook.

These five chefs, and their five recipes, should help do away with those conjunctional interjections. Their inspired dishes elevate the fulsome elegance of wild-hog meat while tamping down the uncultivated aspects that have saddled it with a bad rap. And they should inspire you to give wild hog a try, if only on a plate. Butcher shops and meat purveyors such as the Ingram, Texas–based Broken Arrow Ranch and the renowned D’Artagnan are good starting places.

“What’s fun about these big meats is that they give you so much room to move,” says chef Matt Bolus, of the 404 Kitchen in Nashville. “They handle plenty of pepper heat and strong accoutrements like mustards. You can deglaze the pan with flavors like whiskey and brandy. And there’s more margin for error. You don’t want to overcook any wild game, but cooking wild hog is not like you’re babying truffles on the stove.”

RECIPE: 1 • Chef: Isaac Toups • New Orleans, LA

The Cajun Chop

A wild pork chop with a Louisiana pedigree

Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

A few years ago, Isaac Toups drove into his father’s deer camp on the Louisiana-Mississippi line to find that his dad had shot and skinned a wild hog, rubbed down the whole carcass with salt, pepper, and Creole mustard, and had it waiting for him in a giant cooler. “The only chef’s tool I had was my pocketknife,” Toups recalls, “but we went to work.” Toups wrapped the hog in chicken wire, threaded two lengths of rebar through the carcass for handles, and slow-roasted it over wood from an oak that had fallen nearby. “That was some rudimentary shit,” he says, laughing. “But now they beg me to come back every year.”

Not all of Toups’s efforts are so elemental. He spent a decade working the stoves of Emeril Lagasse’s kitchens, and as chef and owner of the acclaimed Toups’ Meatery in New Orleans, the proud Cajun—his family has been in Louisiana for three hundred years—has been a James Beard Award semifinalist three times. Wild hog, he says, “has a definite role in the Cajun repertoire.” While he often uses healthy doses of aromatics such as cumin and coriander, this pork chop relies on a tangy sweet gastrique. “It’s simple, just syrup, butter, and vinegar,” Toups explains. “But the first time I put it in my mouth, jack, it close to knocked me down.” His version is characteristically hyperlocal, an alchemical brew of Louisiana-born Steen’s cane syrup and cane vinegar.

The domesticated-pig version of this recipe is a Toups’ Meatery staple he serves over his signature dirty rice. But using wild hog deepens the taste—and the experience. “The brine helps keep the chop juicy since you have to go with a little higher temperature on the wild boar,” he says. “It’s intense and earthy, and the more you eat, the more you get that wild goodness just ingrained in you.”

RECIPE: 2 • Chef: Jesse Griffiths • Austin, TX

Boar with All the Fixings

A Yucatán-inspired approach to wild-boar backstrap

Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

Jesse Griffiths’s first book, Afield: A Chef’s Guide to Preparing and Cooking Wild Game and Fish, was a soulful revelation on the nourishments—physical, mental, and spiritual—of wild eating. Now he’s on a mission to demystify wild-hog cooking. Due this spring, his next opus, The Hog Book: A Chef’s Guide to Hunting, Preparing and Cooking Wild Pigs, includes more than a hundred wild-hog recipes, plus deep dives into hog hunting, butchering, and the animals’ natural and cultural history. “I’ve taught many classes on butchering and cooking venison, and the elephant in the room is always the wild hog,” he says. “Someone always raises their hand and says, ‘I know this is a class about deer, but…’”

Griffiths’s cookbook writing is a side gig to his real twenty-five-hour-a-day job, running his regionally focused Dai Due Butcher Shop & Supper Club in Austin and his New School of Traditional Cookery, with immersive classes devoted to hunting, fishing, and butchering skills. “There’s long been a one-size-fits-all approach to cooking wild hogs,” he laments. “But a wild hog can be fifteen pounds or three hundred fifty pounds. It’s disingenuous to approach them all the same way.” In his book, Griffiths divides wild hogs into four classes—small hog, medium hog, large sow, and large boar—and exults in the possibilities of each.

This bright, accessible table stunner is a winner, he says, because it works with hogs of any size—and it might just be “the end-all recipe for big boar backstraps.” Poc chuc has roots in the Yucatán, where pounded-thin pork steak is marinated in a sour orange concoction and cooked “over a ripping hot fire,” Griffiths says, “preferably something with character such as mesquite.” Sour oranges can be difficult to find, but it’s easy to get close with his combination of lime and navel or Valencia orange juice. His two salsas—one a traditional habanero sauce, the other a thicker avocado and mint potion—interact with the robust flavor of the meat in different ways: one a spicy exclamation point on the edgy notion of a meal of wild hog, the other a pleasingly tame approach.

RECIPE: 3 • Chef: Matt Bolus • Nashville, TN

Secret Sauce

Fresh pesto livens up this boar Bolognese

Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

Before landing in Nashville, chef Matt Bolus graduated from Le Cordon Bleu in London, worked knives at the city’s Blagden’s fishmongers and Allens of Mayfair butcher shop, and served as a butcher and fishmonger at Charleston, South Carolina’s esteemed FIG. He opened his 404 Kitchen in Nashville in 2013. But Bolus, a passionate hunter, loves going back to his roots. He grew up in a log cabin in East Tennessee and would visit his grandparents’ farm in Kentucky, where his grandmother paid him a quarter for every bullfrog he could gig.

His Bolognese sauce began life as a “family meal” for his staff, and it became so popular, he says, “we jumped off in all kinds of directions.” He’s made the sauce with beef, pork, black bear, lobster, and mixed seafood. In the summer, he’ll bring in yellow tomatoes and peaches and deglaze the pan with gin. In the fall, pumpkin and sage provide a seasonal backdrop. But spring, he says, is a trickier time for the gravitas that comes with a meal of wild boar. “Part of our brain is saying that it’s time to get our bikini bodies in shape,” he says, laughing, “while another part is not quite ready to give up on eating big.”

The bright tastes of the herbs and citrus in this sauce help cut through the richness of the boar meat, which Bolus treats with particular care. Overfilling a pan tends to simply steam ground meat, he says, which adds an odd texture and does nothing for the flavor. Instead, he creates thin burger-like patties and cooks them hot to caramelize the surface and leave behind copious amounts of crispy, browned fond. “Really push that ground meat,” he advises. “Get it dark brown, and I’m talking about damn near burnt.”

RECIPE: 4 • Chef: David Bancroft • Auburn, AL

Going Whole Ham

Curing your own wild-hog ham is a lesson in patience, with a stunning reward

Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

The taste of wild game “is incomparable,” David Bancroft says. “You can put any label on any cut of meat—free-range, hormone-free, antibiotic-free, stress-free, pasture-raised—and it will never give you what a truly wild animal does.” And for a hunter, there are qualities that go beyond labels. “What I like most,” Bancroft says, “are the added notes of responsibility and self-sufficiency.”

An avid hunter and gardener, Bancroft opened his lauded Acre in downtown Auburn, Alabama, in 2013, and his barbecue restaurant, Bow & Arrow, in 2018. He’s a charcuterie aficionado, and Acre partners with the Auburn University Lambert-Powell Meats Laboratory to fine-tune humanely raised and artfully butchered meats. This cured wild-hog ham is a labor of love. From start to finish, the process will take months, and it will be complete when it is complete. “The ham is ready when it has lost a third of its weight,” Bancroft explains, and how long that takes is a function of the environment in which it is hung. “It’s a very accurate way of measuring,” he says, “but it stinks when it comes to the patience game.”

If you want to try curing your own ham, Bancroft suggests you first find the right frame of mind. To help while away the time, he tries to “step into character and tap into the artistry and appreciation of our ancestors who approached these animals in this way. There’s a sense of intentionality about curing a ham.” Revel in the process, he advises, and you won’t rush the final product.

RECIPE: 5 • Chef: Alexandra Gates • Marfa, TX

Meatballs à la Marfa

A little European, a little Texan, this dish is all comfort

Johnny autry | Food Styling by Charlotte Autry

The first time Alexandra Gates visited Marfa—a small high-desert West Texas ranching village with an outsize reputation as an arts center—the California native had a surprisingly visceral reaction. “Marfa is surrounded by these beautiful ranching landscapes,” she recalls. “They may be complete opposites in so many ways, but I had the exact same reaction upon seeing New York for the first time: I have to live here.”

Gates’s mother is Swiss, and she grew up spending her summers with her grandparents in the foothills of Switzerland’s Alps. Her grandfather often went fishing in the early hours before work, and she would wake to find the bathtub filled with fish, which she and her grandmother would clean and cook. “Between that and having so many international friends from growing up in California,” she says, “I developed a very European perspective toward food.”

After stints in New York kitchens, Gates moved to the Lone Star State with her husband, a Texas native, and continued her eclectic culinary approach in Austin: She ran an acclaimed food trailer serving Spanish-inflected foods, and served as the executive chef for the boutique Hotel Saint Cecilia. She opened her Marfa restaurant, Cochineal, in a 1920 adobe building and promptly began melding her heritage of European cuisine with a full-throttle love of Texas. “I immediately fell in love with the wild-game scene,” she says, and the restaurant nearly always offers some brand of game, from nilgai antelope to elk and quail. And wild hog. “Sometimes they are very sweet, and sometimes really herbaceous,” she explains. “Are they eating acorns or prickly pear? They are a complete expression of their environment.”

This dish articulates Gates’s international influences. She first discovered meatballs in an almond sauce on a trip to Spain. “So I tried to Americanize that with the whiskey,” she says. And the addition of wild hog makes it a delicious love letter to her adopted Texas home.