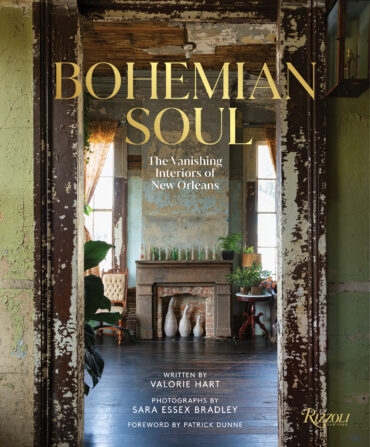

Homeplace

Step Inside a Bright and Boisterous Bourbon Street Cottage

You can literally step inside—during Mardi Gras or just about any time

Photo: HECTOR SANCHEZ

On the plot of land numbered 211 on a 1728 map of New Orleans, Heather Harllee’s three children have found treasures: willowware china; old shoes; handwrought nails; a pirate’s map on graphing paper; glass bottles from the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia, when West Virginia was just Virginia; an icon of the Virgin Mary; railroad spikes—possibly for spiritual protection; children’s initials carved in a door.

In 2010, soon after Harllee bought the Creole cottage on lower Bourbon Street in the French Quarter, her contractors lifted the house on jacks in an effort to replace a rotten sill. Her daughter, Caroline, would dive underneath where it was dark and come up with bones, relics of a nineteenth-century grocery business run by Felix de Lille, a free man of color who had served in the War of 1812. “She wasn’t afraid at all,” Harllee says. “And she’s still not today.”

The cottage on Bourbon is a place that makes people feel comfortable, and invites them to stick around. During the nearly fourteen years Harllee has owned it, three generations of her family have called it home. In 2019, Caroline’s wedding took place in the house. Three years later, Harllee’s mother, Amie, moved in. Most mornings, her grandson toddles down the block to spend the day.

Photo: HECTOR SANCHEZ

Situated above a linen velvet sofa in the living room, an eighteenth-century painted leather screen was the first piece designer Jared Hughes bought for the house and inspired much of the home’s color palette.

Harllee herself has known the house her whole life. She attended her very first Mardi Gras party there, hosted by the cottage’s previous owner Yvonne “Miss Dixie” Fasnacht. A clarinetist and co-proprietor of Dixie’s Bar of Music, Fasnacht was a key figure in the city’s gay community. Even after the bar closed in 1964, her patrons—men like Tennessee Williams, Rock Hudson, Clay Shaw, and Truman Capote—continued attending parties at her home, where she received them with love, laughter, and Hurricanes. “It was a very lively place,” Harllee remembers. And she has made sure to keep it that way.

Harllee, whose Creole ancestry in Louisiana predates the founding of New Orleans, is committed to preserving the house’s history, however it manifests. After restoring the residence—once divided into apartments—to its original floor plan of three bays, each two rooms deep, with a loggia running across the back, Harllee tackled the decor, enlisting the Atlanta designer Jared Hughes, a virtuoso of storied spaces.

When he’s decorating a historic home, Hughes says, he aims to make it feel as if “it’s always been there,” by assembling a collection that seems to have evolved over the course of the house’s life span. Here, that meant mingling gilt bergères and chinoiserie with venetian glass, mythological paintings, and fresh draperies: an acknowledgment that the French Quarter has been not just French but Italian, decadent, and soigné. “We had a lot of different styles to pull from to create a great mix,” Hughes says.

Keeping Fasnacht’s tradition alive, Harllee throws an open house every Mardi Gras, setting up a bar on a parquetry chest under a nineteenth-century oil of “Marty”—an “ancestor” found at auction—and a 1962 street portrait of her mother. A buffet anchors the dining room, where Hughes built bookcases around the wraparound Creole mantel to house Harllee’s library. An accomplished cook, Harllee keeps the door closed to her airy kitchen, where a print of Audubon’s Nuttall’s Hare hangs above a possum-belly baker’s table rescued from a neighbor’s bed-and-breakfast.

Photo: HECTOR SANCHEZ

An antique Italian commode with parquetry inlay in the living room holds treasures; sunlight streams into the loggia.

To bounce light around the space—and brighten the interior rooms—Hughes suggested adding color to the walls, floors, and ceilings. Farrow & Ball paint in Dead Salmon warms the loggia, while Pointing and Green Smoke make the dining room hum. In the living room, a Sudbury Yellow ceiling reflects the Setting Plaster walls, so that “at sunset, when the western light comes in,” Hughes says, “the entire room becomes a romantic blur of pink and yellow light.” To satisfy the dictates of historic preservation, the design team needed proof that the ceiling had been painted before, so Harllee climbed a ladder to look for traces of color between the cypress boards. Of course, she found them. The cottage’s Creole owners, it turns out, have always had it right.

Now, during Mardi Gras and after Saints games—or just any old time—visitors step in off Bourbon Street into a world wrapped in color, an enfilade of dusty pink and green leading to the loggia, where arched windows open onto the courtyard. Sunk in a rattan armchair, basking in the slanted sunlight, you might find it hard to leave. The house itself seems to embrace you: The walls create pockets of privacy, their sturdy briquette entre poteaux construction muffling the revelry outside. “During parties, all these little private kinships develop around the house,” Harllee says. “People stay a very long time.”