Travel

The Hidden Caribbean: An Island Education

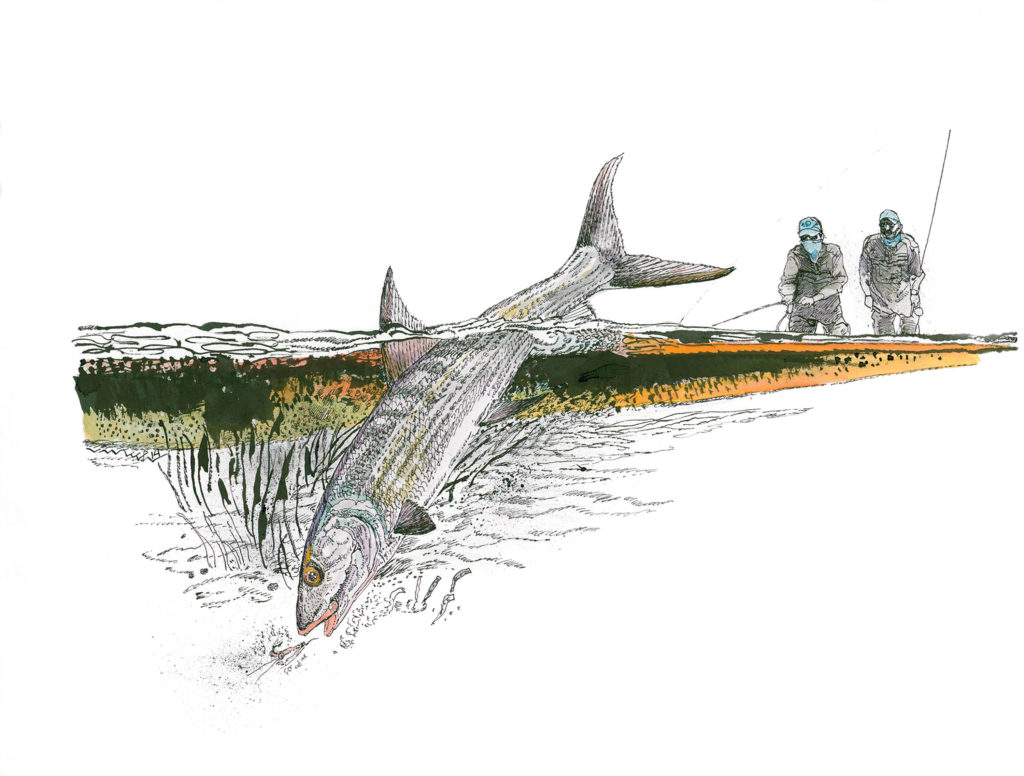

Illustration: Jack Unruh

By the end of the 1957 academic year, the headmaster of the boys-only French boarding school I had been attending made it clear to my parents that the odds of their son’s passing his baccalaureates were not worth betting on. With little ado I was flown across the Atlantic Ocean and enrolled into a coeducational boarding school in southern Florida where, it was presumed, the curriculum would be better tailored to my abilities. The student body in that school comprised fifty boys and seventy girls, and to my undying gratitude, twenty of those girls were gorgeous. After I spent six years in an institution where gray clouds, cold rain, and corporal punishment (the act of caning was looked upon as a métier) were everyday occurrences, Florida—the state of sunshine, tan lines, and sexual fantasies—is where I matured in all regards, except scholastically.

In the spring of my first year, Gilbert Drake, a student two years ahead of me, invited three of his friends to his father’s newly acquired island located off the east end of Grand Bahama Island. Deep Water Cay, which the Drake family had leased from the British Crown for ninety-nine years, was a narrow, two-mile-long spit of sand and coral that they would soon fashion into the best bonefishing camp in the Bahamas.

Over the months and years, Gil and his brother Tommy, as well as a succession of contractors, built the dock, generator house, lodge, guest quarters, private houses, and airstrip. I came and went as often as school and family obligations allowed and was generously provided with room and board, against what limited help I could provide with the jobs at hand. My mechanical skills did not match my unlimited enthusiasm, and it soon became apparent that my inclusion into the Drake family was at my friend’s insistence. Of those years I possess more memories than it is possible to have lived, but I was young then and happy to fight windmills. Just as I now forgive my son for aggrandizing the memories of his youth, I forgive myself for making up a few of my own.

Before the lodge was built, we slept on the deck of the Magic, a wood-hulled thirty-six-foot Nova Scotia inboard, anchored in the current of the creek to confuse the mosquitoes. The island was short on amenities. For a long time frozen meat and poultry, fresh vegetables, fruit, and even blocks of ice were imported from Nassau. Gil and I would take turns running a skiff out to deep water on the far side of the reef and guiding the rusty sixty-foot supply ship through the natural and dynamited gaps and corridors in the coral leading to the lodge.

Before the lodge was built, we slept on the deck of the Magic, a wood-hulled thirty-six-foot Nova Scotia inboard, anchored in the current of the creek to confuse the mosquitoes. The island was short on amenities. For a long time frozen meat and poultry, fresh vegetables, fruit, and even blocks of ice were imported from Nassau. Gil and I would take turns running a skiff out to deep water on the far side of the reef and guiding the rusty sixty-foot supply ship through the natural and dynamited gaps and corridors in the coral leading to the lodge.

The Magic made half a dozen trips every season from South Florida across the Gulf Stream, carrying whatever was needed to build a fish camp. When I would join Gil for the trip, we would leave West Palm Beach at dawn for the five-hour crossing to Freeport and point the bow of the Magic at the rising orange ball of sun that greeted us as we left the inlet. At times it was a long, quiet ride through the infinity of a young man’s dream, a perfect adventure with danger hiding so far below the hull that it never rose to the immediacy of reality. But the Gulf Stream had a habit of turning without much warning from the calmest horizon to a fierce old fighter, gray and screaming and unpredictable because of the direction of its current and the wind that challenged it. As teenagers we felt we understood the sea and how to deal with its particular fickleness, which at any rate turned out to be effortless compared with the moods of the girls we dated.

After a few years into the building of the camp, Cessna 310s started using the coral-and-grass strip we had helped carve out of the mangroves, ferrying guests from the mainland to Freeport, and then from customs to the island, where a tractor-pulled wagon greeted the plane. Taking off from Deep Water Cay with five full seats and the absurd amount of baggage that anglers, to this day, insist is de rigueur for catching a five-pound fish was an experience I qualified as a “holy shit” moment. More often than not, the second turbocharged engine refused the hot start. So while the passengers sat in their seats at the end of the runway, staining their city clothes with sweat, the pilot would crank and crank on the engine until suddenly the plane bucked and howled into life. It was then a matter of applying full power while standing on the brakes and, when the 310 hunkered down and felt like it was going to disintegrate, letting go. Determined to meet the passengers’ connecting flights in Florida, the pilot would lead the Cessna around a magnitude of rising clouds and rain showers, and through the ephemeral beauty of Southern rainbows. Predictably, turbulence was present to greet the plane every time it lifted off the ground.

In June the water was warm and clear and as yet unhindered by the proliferation of plankton that would bemuse the ocean during the oppressive days of August. Tremendous cloud formations reached up into the sky every afternoon. Late in the evenings they fell into the ocean in avalanches of rain and lightning and thunder. When it was dark and a mature storm chose the east end of Grand Bahama to flex its authority, thunder rolled across the flats like the outbreak of war. The sounds of doom and disaster were such that I would crawl under my bed and lie facedown, holding a pillow over my head.

Gil and I, like most young men, enjoyed tempting fate. On any given day we would run one of the lodge’s fourteen-foot bonefish skiffs out of sight of land to look for something, anything, out of the ordinary. We free dove in a thousand feet of blue water with miniature dolphins and sailfish under mats of sargasso weeds. We chummed for sharks among schools of yellowfin tuna, and if the opportunity presented itself, we would run the skiff up the back side of funnel clouds and, from a football field away, watch the gray column of water vacuum the ocean into the sky. As often as we could, wet and caked in salt, we would hang on to the bow rope and ride the skiff like a horse, burning a trail of adventure across the greatest playing field on earth: the sea.

Years passed before I would realize how lucky I had been to live on a Bahamian island in the late fifties and sixties, a time when phone calls to the mainland could take days, when the affairs of men were sealed with a handshake, and when the sport of saltwater fly fishing was in its infancy. We waded the flats without ever stepping in the footprints of another angler and dove in water so clear our shadows mottled the sand below us. What were everyday events to us are to most people today inconceivable.

Photo: Courtesy of Guy de la Valdéne

Riding the Tide

Gil Drake, circa 1960, hunts the reefs off Deep Water Cay in search of dinner––and a thrill.

Gil and I defined adventure as anything unusual, memorable, or frightening; if the concept of beauty entered into the equation, all the better. Bonefishing did not meet any of the criteria, but being dragged through the water by a speared lemon shark met them all, as did floating on top of a thirty-foot reef at night without a light. Snorkeling across a shallow, white flat and being swallowed into a bottomless blue hole where snappers and amberjacks patrolled the entrance also qualified. In those underwater caverns the reef fish waltzed and the prismatic reflection of the sun on the walls of the cave wrapped itself around us as we descended into a honeycombed world of tunnels and corridors, at the bottom of which lay sleeping sharks.

There were days that, encouraged by the tide, we snorkeled over miles and miles of reefs, our masks wondrous magnifying glasses that exposed us to the green heads of moray eels, the wide pink lips of conchs, the simpleminded advances of hogfish, the exaggerated eyes of Nassau groupers, and the occasional school of bonefish patiently waiting for a surge of water to carry them onto the flats. In deep water the bonefish were unassuming, bland, and undistinguished for being a single member of a school with no apparent purpose. In shallow water the subtle blending of mangrove colors on the fish’s head and back, the milk white of its belly, and the breath of powder blue on the brow of its fins transformed bonefish from bottom-feeders to the speeding darlings of the angling community.

Gil and I, however, wanted fish that pulled, fish that jerked and tugged and dove and tried to rip the rod out of our hands, fish like marlins and sharks and tunas. We liked casting and dragging wooden plugs across the reef at night, plugs that under the light of the moon left iridescent contrails below the surface. We loved being startled by the slashing of water triggered by a barracuda sideswiping the lure, and the way the sea blew open when a grouper rushed the plug from below. In general, we looked for anything that put up a fight, with special emphasis on the unfamiliar.

Black-and-white photographs of us from those early days portray thin boys in black tank suits, all knees and elbows, awkward in demeanor and yet wearing the know-it-all smirk of youth; boys caught on film between adventures; boys who dove with fins and snorkels and speared everything in sight, including huge stingrays for the thrill of being dragged through the water by genetically old creatures destined to die before the day was over. On moonless nights we would test our manhood by standing at the end of the dock tethered to a rope tied to a hook and a big chunk of fish. The bait settled to the bottom a hundred feet out in the falling tide, and we waited for the inevitable shark to pick it up. The winner fought the shark back to the dock or followed it overboard; the loser cut himself loose before being dragged in.

We snorkeled the shallow reefs at night with cheap flashlights and broom handles and laughed hysterically when forced to fend off those small blacktip sharks interested in our fins. At night we dreamed of treasures and billfish and island girls, ever confident in what the new day would bring. Moray eels, rays, sharks, turtles, ducks, pigeons, and more were all there for the taking—for the sport, for the eating, and to fulfill a basic wish in men young and old to exert dominion over the natural world. Even though we eventually outgrew the need for killing, fishing was in our blood and would remain a part of our lives forever.

Our favorite time to be on the island was in the summer after the lodge was closed to the paying guests. It was then that the realization of every sporting dream was simply a matter of waking up. We left the dock each day after breakfast loaded with fishing tackle, diving gear, and sometimes a floating, collapsible shark cage made out of PVC tubing. We’d take refuge in the tubing while we photographed those sharks that got overly excited at the chum we bled into the water.

Days that started with the vaguest of plans were invariably amended and shaped to conform to the weather and the mood of the moment. Sometimes we shot flying fish from the bow of the skiff while running wide open over flat calm water, our targets reflecting the sunlight before spinning into the blue, out of sight. Other times we chummed the ocean for whitetip sharks, for the thrill of watching them rise out of the ocean and—more to the point—for the thrill of scaring ourselves senseless. In September we would hunt legions of crayfish—lobsters—marching single file in the lee of shallow coral reefs. We dove for them, gigged them, speared them, and ate them fresh, prepared by big, cheerful black women from McLean’s Town, one cay over from the lodge, women who shuffled across the kitchen on heelless shoes and fussed at each other while they cooked. Superstitious women, who, at the mere mention of Condosha, the ghost of an African slave resurrected as a black dog that ate human flesh, would run off the cay terrorized and not return for days.

We lived in the present, because that’s what young people do. When a frigate bird spread its black wings on the wind or a sailfish billed through a school of bait, when the creek took on the deep delight of greens and blues that swept in from the ocean, overflowing the flats with fresh water and food, we didn’t define the moment as anything other than being alive. Dawn was a pale affair, a triumph of gradualism and the preface to a new adventure; nights were thick with the sounds of insects and crabs, the pleasures of exhaustion, and the wonder of dreams.

Imagine a mirror granting every wish, and then imagine looking into that mirror every single day.

It was at the long communal dinner tables inside the lodge that drinks and food found comfort in the souls of the paying guests. The anglers were for the most part middle-aged or older men and women, CEOs of active companies and retired businesspeople from New England, guests with oddly pompous accents and money to spend. Overall good people, the guests dressed in universal khaki and brought with them high expectations. They had paid not only to fish but to be pampered, and in the evenings they confidently put forward their opinions on a variety of subjects.

Piscatorial geography, fishing lodges, boats, guides, lures, and of course politics were the foundations of the energetic diatribes that two or more martinis at cocktail hour drew out of the otherwise polite, conservative guests. Unbeknownst to them, they discussed the same subjects, asked the same questions, and put forward the same conclusions the anglers they had replaced had submitted the week before. After a day in the sun, a few drinks could turn these civil men and women into Jekyll and Hydes whose voices rose in proportion to the liquor they consumed, until half a dozen well-educated New Englanders were braying like donkeys.

Gil and I considered bonefish as undemanding to catch as a grunt, and we could not understand the nightly arguments related to the angling techniques applied to Albula vulpes. A spinning rod, a shrimp on the hook, and the wherewithal to land the bait inside a target the size of an armchair at sixty feet ensured a grab. Most of the guests who visited the island did not display that particular ability, however, and were delighted to release three or four fish a day. These caricatures of our future selves—old men with white hair, bony heads, and soft bodies—were to us of bleached hair and tanned feet cause for unending wonder.

The Deep Water Cay guides were from McLean’s Town. With thick Bahamian accents they told and retold stories of their fathers sailing eighteen-foot dinghies south to Cuba for sugar and as far north as the Carolinas for liquor. They passed on the legends of treasure inside ships torn open on reefs during hurricanes, and of their whereabouts in relation to a spit of land, a depth of water, or a familiar cove. Dark men of varied ages, their ancestors had been abducted from West African villages, transported in chains across the ocean in the guts of slow-sailing vessels, and put to work by men who displayed more empathy for the life and death of their livestock than those of their slaves.

The children of those first slaves had survived the rhythms and rigors of life on the nonvolcanic island of Grand Bahama—an island that rose out of the sea through the pressures of time, an island of simple beauty but lean of earth, vegetation, and compassion. In turn, their children now survived by harvesting bonefish with nets, crayfish with tickler poles and gigs, reef fish with hand lines, and conchs out of small dinghies.

Some of the guides were better than others, but they all wore radiant smiles bright with hope. They could see fish on the flats without the help of anything other than the eyes they were born with—the same eyes that would cloud over later in life from decades of staring through the reflection of sun on water—fine men with one foot in the past and the other in a tentative future as bonefish guides to wealthy men and women.

Regulars at Deep Water Cay included such famous anglers as Al McClane, Tom McNally, Joe Brooks, and other professionals who had introduced the sport of saltwater fly fishing to trout fishermen, men who had caught the strongest, wildest, and heaviest of all fish on fly. These men came back to the island year after year, in part because of their friendship with the owner, Gil’s father, but also because they beheld fishing the flats as a pilgrimage and hooking bonefish on fly as a hallowed experience. We talked to them, these skilled men with tough hides and narrow eyes, learning from their stories, their egos, their lies. We saw in their faces our own mortality. But when it was all said and done, the difference was fundamental: We fished as children do, for pleasure, while these men fished for a living, and something about that forgave us in the eyes of God.