Arts & Culture

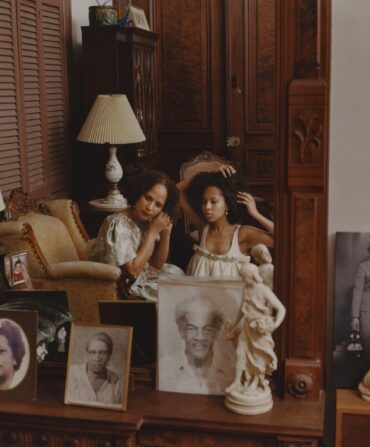

The Lady and the Tiger

Renowned Southern man of letters Pat Conroy reflects on his personal journals

Photo: Andy Anderson

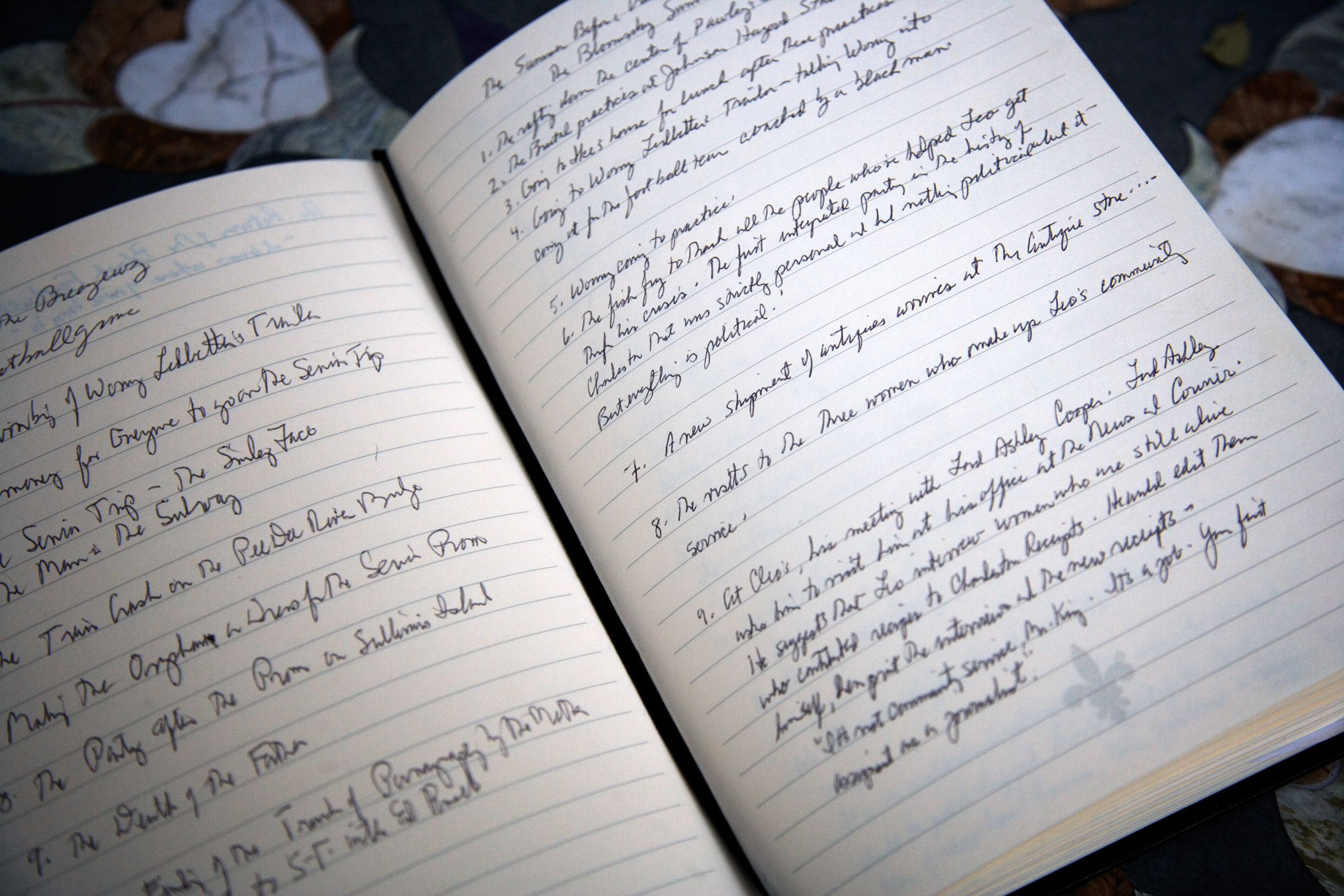

Whenever I begin to write a new novel, I take an unhurried walk through the various journals I have kept over the years. It grieves me that I have not kept a thousand promises to myself to become a more avid and obsessional journal keeper, but my record is haphazard at best, dispiriting at worst. Over the years I have met a disciplined battalion of writers who would not think about starting their day without making careful notations of their thoughts, joys, passions, and observations of the day before. I consider it a damning critique of my character that I have not kept to a stricter schedule in the keeping of journals over the years. They are brawny and scrupulous during the winter time, but the entries grow rare during springtime and seem to peter out almost completely by autumn. It takes only a random search of my earliest journals to see that every book I have ever written can be traced back to the first wing beats of my attempts to bring order to the chaos and discomposure I brought to the writing. Since I was a sixteen-year-old boy, the journal has never been a confessional or dream-saver, but always a place where my deepest memories went to hide. But it was not until I was spending two years in Rome, Italy, that the journals and time and memory all conspired in a single moment to teach me a lesson in how a novelist’s mind works when everything collides and registers in a perfect, rounded-off moment. The journal is a place I turn to when I feel the pilot light of my imagination turned off.

I wrote the first five hundred pages of The Prince of Tides while living in a house on the Via dei Foraggi, with a palm-shaded deck overlooking the Roman Forum. Since I was writing a book about a shrimping family who lived on a sea island near Beaufort, South Carolina, I needed to depend on the accuracy and profusion of details I had entrusted to the journals I had kept in such a desultory fashion over the previous ten years. Rome would teach me many things, but it could not reveal a single thing to me about the great salt marshes of the Lowcountry, or the migration of shrimp that was the life’s work of the father of my fictional family. Their voices were beginning to call out to me both in my sleep and in my waking hours, when I would walk the streets of Rome with the sound of Southern voices springing to immediate life inside me.

In one journal I found a description of my Jacksonville, Florida, uncle, Joe Gillespie, who held a fascinating grip on my imagination as a child, and who seemed larger than life many years before I even knew what larger than life meant. Uncle Joe had done me the immense favor of sharing his dreams of becoming a millionaire when I was a very small boy. His ideas were profligate and multi-varied and fabulous in his generous articulation of all of them. Once he told me of his plan to buy Rock Springs Park in Apopha, Florida, and make it available only to royalty and titans of industry and other millionaires like himself. When that fell through, he talked about starting a series of putt-putt golf courses that would showcase moments in the life of Christ from his birth in the manger to his resurrection from the dead. Later, he would let me in on the secret that he was planning to corner the goat cheese market in America, after he had converted his stock from his ownership of a day-old bread company in Jacksonville. Once he was going to set out for Hollywood because he had mastered the techniques and mysteries of film (and his family movies are still highly prized artifacts among his children and relatives). In my entire experience of knowing Uncle Joe, he never once let me down by not sharing some absurd or magical contrivance that would bring countless millions to his bank account and considerable reflected glory on those of us lucky enough to be related to him by blood or marriage. Putting my journals to good use, I incorporated the wild, capitalistic schemes of my Uncle Joe into the biography of my shrimper, Henry Wingo, and I did it with relish and gratitude that my Aunt Evelyn had once fallen in love with the handsome naval aviator, Joe Gillespie.

Then my journal work threw me one of the many curveballs that a journal can hide up its sleeve as it lies in wait for the writer to return to its pages. I came across a casual reference to “Happy the Tiger,” and with a suddenness that delighted me, I knew how Henry Wingo was going to make his colossal fortune. So this is how a novelist thinks and works, I thought, as I began to weave the story of the shrimper and the tiger in the first pages I wrote for The Prince of Tides.

I had wanted to write about Happy the Tiger since I first encountered him on the corner of Gervais and Devine streets at an Esso gas station in Columbia, South Carolina, when I was still a cadet at The Citadel. My indolence as a journal writer draws a strong illustration by the fact that I provide no dates or details of my surprise encounter with a Bengal tiger at a gas station in the middle of the capital city of South Carolina. But the encounter proved fruitful and unforgettable to me as I conjured up the image of a lost tiger as I wrote a book about the South as I lived in a city where the Caesars once walked along the Palatine Hill behind me. I took that as a sign from the Roman gods, and I named the tiger Caesar.

It is my personal belief that a novelist gets very little material for books by merely filling a car with gas in America or anywhere else. But I had hit a motherlode that day when a young attendant told me that I could get a free car wash and feed the tiger if I filled my car with gas. Since I was famous for having a car that always needed a wash, I agreed immediately, then asked, “What do you mean, feed the tiger?” “Just what I said,” the boy said, looking over toward the car wash. In a small cage, in the man-eating summer heat of Columbia, there sat a full-grown Bengal tiger in his magnificent prime. Esso gas had circulated a popular commercial for several years that promised you would be “putting a tiger in your tank” every time you chose to use their product. The enterprising owner of the gas station capitalized on the advertisement and bought a live tiger from a financially troubled traveling circus, placed the tiger next to his car wash and increased his business tenfold by his ambition and foresight.

A fiction writer is the master of ceremonies, fabulist, puppet master, sleight-of-hand artist, gun slinger, Pacific fleet, and a thousand other identities of the novelist’s robust art. But I found myself in quicksand, trapped by my own invention with no way out.

Children in Columbia would beg their parents to go to that Esso station so they could feed Happy the Tiger. As the young man hooked my car up for the free wash, I pulled some chicken necks out of an iced-down cooler and approached the tiger’s cage. From out of the shadow and deep heat that tiger came out of its corner, with all the beautiful fire that wildness can bestow, and he would have torn my head off if I had gotten near enough to those claws, the size of ten-penny nails and much thicker. Keeping my distance, I threw the chicken necks through the bars and the misnamed Happy the Tiger inhaled them as though they were breath mints. My admiration for the strength and magnificence of tigers was set for life. Every time I was anywhere near Columbia, I went to that Esso gas station for a fill-up and the great honor of feeding a Bengal tiger.

My conscience often bothered me about Happy, and over the years I kept up with his disheartening and tragic destiny. Someone told me that a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals came to town and had himself a conniption when he witnessed the living conditions of this unfortunate beast. By this time, the whole state had fallen in love with Happy, yet understood that his living conditions were cruel and unworthy of a state that knew better. It was because of Happy the Tiger that the city of Columbia started to form the committees among the citizens and the legislature that would lead to the creation of the Columbia zoo, along the banks of the Saluda River. The original idea for this superlative zoo was to provide a suitable home for the tiger who had lived too long among gas tanks, motor oil, and the incessant sound of a car wash. Happy the Tiger was the first resident of the zoo, a gift of the gas station owner, and funds poured in from around the state in honor of Happy.

When the zoo broke ground, it was cutting-edge and dazzling and the pride of the whole state from the day it opened until the present day. But Happy’s dilemma continued to haunt the lives of all who held him in both affection and awe. When he was released to live out his days in a state-of-the-art habitat, the other tigers, who had actually been born and captured in the jungles of India, sniffed out the presence of a bogus, spoiled-brat-of-a-gas-station tiger immediately. The legitimate tigers, who had grown up with the smell of elephant herds and the spoors of fallow deer in their nostrils, were not about to welcome into their aristocratic mix a tiger who cut his teeth on chicken necks and Big Macs. They almost killed Happy the Tiger during the first days’ residence, and the zoo keepers had to segregate Happy from the others. But we had long been experts in segregation in South Carolina, and they moved Happy to another enclosure, where he began to die of solitude and starvation. The tiger that South Carolina had both adored and ruined refused to eat, and its unhappiness stirred the deepest compassion in the men and women entrusted with keeping him alive.

Finally, a zoo keeper had an inspired idea and moved Happy the Tiger to a cage the exact size of the one he had lived in at the gas station. There was some notable improvement, but it was not until the zoo installed a sound track of a car wash that played for twenty-four hours that South Carolina’s favorite tiger was able to achieve any sense of real peace or equanimity. It was there that Happy spent out the rest of his days, with as much contentment as any tiger with his calamitous history could expect. When Happy died, people mourned his death the length and breadth of South Carolina. Whenever I visit the South Carolina zoo, I always pay homage to the statue of Happy the Tiger, which is located outside of the enclosure where the great cats stretch in the sunlight.

So a brief notation in my first journal caused a reverie in Rome, and I let the alchemy of fiction do the heavy lifting as I blended the story of my Uncle Joe’s elaborate plans to make a million bucks with the fictional history of a shrimper who buys a tiger from a traveling circus, places the tiger in a cage outside of an Esso station, and nearly bankrupts his family in the process. Even as I wrote it, I could feel the story straining at the leash, but I was trying to write a novel more ambitious than anything I had ever done before. I had sworn for years that I was going to find a place for Happy the Tiger in one of my books before I died. When the gas station failed and Henry Wingo returned to shrimping the waters he had grown up in, I put the Bengal tiger into the Wingo’s vast backyard, gave the job of feeding him to the oldest Wingo boy, and forgot all about the only tiger I had ever fed by hand. For me, as a novelist, it was an easy task to forget the presence of a tiger in the backyard when I had another one thousand pages to write by hand.

Yet the journals kept surrendering rich yields of stories that struck me with their bright luster and the authority of their originality. On one page I found a reference to an albino porpoise that had swam in the Beaufort River the year I arrived in town. In another journal, I had written down an account of my great Uncle Cicero walking on Good Friday with a wooden cross he had fashioned himself to remind the impenitent citizens of Anniston, Alabama, of their sinful ways, and of an old man waterskiing from Savannah, Georgia, to Beaufort after his driver’s license was revoked because he had gotten too old and infirm to drive.

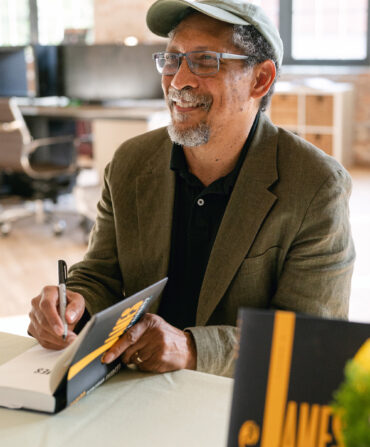

Photo: Andy Anderson

Pat Conroy's journal opens to notes on events he may include in a novel he is now writing

I built up the house of Wingo from the glittering treasury of stories I had thought highly enough of to record in my journal. Without knowing it, I had included the skeletal outlines of a hundred novels simply by jotting down conversations I had overheard in passing, or strange encounters recorded without commentary in the arrest records of small town newspapers. Suddenly, my journals began to appear like treasuries of the imagination, golden hives overflowing with honey that tasted of jonquils and honeysuckle. I had carried my South around in them, and had packed them full of lost moments like the valise of a traveling salesman going door to door with his brushes, what-nots, and notions.

Until I came to Rome, it never occurred to me I could steal from my own life to explain the whole chaotic world to myself. Often, I felt like an armed robber holding my younger self hostage as I robbed a safety deposit box whose password I had forgotten many years ago. I would sometimes blush when I came across absurdities or pretensions that made me seem clownish when I was trying out the high-wires that would lend my writing a philosophical depth I thought I lacked. Losing myself in the rushing, Tiber-scented flow of the language, I would come across a line such as this: “Nostalgia is the indentured servant of memory.” Or this: “In the South I fell in love with the melancholy of extinction. I wanted to hide a colony of ivory-billed woodpeckers in my attic and raise bald eagles in my pigeon coop. By reading, I feel in love with elephants and passenger pigeons.” Or this: “The Southern disease is a poverty of images and a super-abundance of clichés.”

Because these fragments are written down in my own handwriting, I know that I am responsible for what they say, but have no idea as I read them now what I was getting at. I had arrived at the portal where journals became pitfalls – instead of aids to creation. Your writing can become a bear-trap instead of a path to enlightenment. Yet The Prince of Tides surged forward, and I kept finding shards of colored glass, descriptions of high tides, the smells of shrimp boats, and gardens kept by ascetics, and the rantings of madmen that I could use. In one old notebook, I found a description of Tutti, a retarded black man from Beaufort who directed traffic because it gave him pleasure and a sense of purpose, and he led every parade that took place in the town. Because of that entry, Tutti signed his name into the roll of citizens and taxpayers who would spring into the unnatural light of a fictional town, because I had fallen in love with him in a real one.

As I wrote, I kept a careful journal of my life in Rome, and without knowing it had begun the process of creating my next novel, Beach Music. Walking the streets of Rome, I tried to make the city enter the pores of my flesh and to pass my own inconsequential history into its immortal stones. In a lifetime of self-improvement, I thought that Rome was the greatest gift I had ever given myself. I took in its bruised colors, and its insatiable marketplaces, and the glorious shapes of its palazzos and ruins. Then, I received a phone call from my weeping brother, Mike, informing me that my mother was in a coma and dying of leukemia. Later that month, I heard that a beloved great-aunt had been brutally raped in Atlanta and her arm broken during a savage and unimaginable assault. I mentioned both incidents in my journals thinking that I would write about these things in a future book. But journals bring their own duties and mindsets to the task of novel writing, and the writer is not in charge of all of them at all, as I was about to discover. Some time, the journal comes disguised as a hand servant, other times it bullies and threatens, and dresses in the robes of inquisitor or tsar. Mine began to dictate what I was going to write in The Prince of Tides, and it refused to be patronized or wait its turn for a future of uncertainty that is the main feature of the writing life.

In a passage written during the time I still wrote with a fountain pen, I stumbled across a reference to the giant I had called Callanwolde when I was a child, and the mystery spun me twisting back in a whirlwind of time to Atlanta, Georgia. Before my fighter pilot father left to fight in the Korean War, he took me aside and told me I was now the man of the house, and he was leaving me in charge to take care of and protect my mother, my grandmother, and my sister. Since it was the year I started kindergarten, I lacked all knowledge of how to be the man of the house.

My grandmother’s house backed up to a magical piece of property with a baronial manor named Callanwolde. It was the home of the great Candler family, whose ancestor had invented a potion known as Coca-Cola. There was a family zoo located on the estate, and a stableful of thoroughbred horses. It was from these woods that a bearded giant rose out of darkness to haunt the nightmares of my mother for a whole fearful year.

I was watching television with my family, and was the first to see him leering at my mother on the glassed-in porch of the Rosedale Road house. Before that night, I had never seen a man with a beard, and I had never seen a man seven feet tall. That is how tall the police said he was as they measured the spot where his mouth breathed against the glass door. I had entered the country of lust and perversion as I realized my mother’s beauty was striking enough to bring giants out of forests created by the enormous wealth of a family made fat by soft drinks. For a year, Callanwolde tormented my mother. Once, we heard him crawling on our roof. My grandmother emptied her revolver once through her own bedroom window, and again through her front door. I learned that my grandmother, Stanny, was a fearless woman and a poor marksman the same year I realized I made a poor man of the house. That I could not even protect myself from this unstoppable intruder was humiliation enough, but that I was helpless to calm the fears of the women of my life haunts me to this day. Callanwolde forced his way into my own realm of nightmare, and he never left me alone, not even when we left Atlanta. The giant traveled with me, taunting me with his wantonness and supernatural strength and his contempt of my smallness, my maleness, my soul. Without my permission, he stormed into the pages of The Prince of Tides. It was a human agony to write about and resurrect him, and it stunned me when, three hundred pages later, he made a return with two convicts to attack the island home of my poor defenseless Wingo family, and for some unfinished business with my mother, who was dying on an island in South Carolina as I wrote my novel. Callanwolde brutally raped the mother, and the other escaped convicts raped the sister and the brother. It was the most horrific, heartbreaking scene I had ever written, or ever want to write.

But journals bring their own duties and mindsets to the task of novel writing, and the writer is not in charge of all of them at all, as I was about to discover. Some time, the journal comes disguised as a hand servant, other times it bullies and threatens, and dresses in the robes of inquisitor or tsar.

Then, in a journal, I read a note I had made to myself after reading a newspaper article about the psychology of escaped cons, especially those serving life sentences. Prison life and long experience in courtrooms had taught them never to leave witnesses to their crimes. Dead people yielded no testimony to crime. Common sense told me that I had placed the Wingo family in moral jeopardy, and I could think of no way for Lila Wingo and her two children to survive this calamitous encounter. The dying of my mother, the rape of my aunt, the journal that mentioned Callanwolde had put me on a collision course to a dead end, an impasse that I could not see my way out of. Though I realized that the other son Luke was out in the woods, I could see no way that an eighteen year old boy could overpower three desperate men who were running for their own lives. A fiction writer is the master of ceremonies, fabulist, puppet master, sleight of hand artist, gun slinger, Pacific fleet, and a thousand other identities of the novelist’s robust art. But I found myself in quicksand, trapped by my own invention with no way out.

For a week I searched my journals and my memory for a way to save three characters I had left bleeding and ravished on the floor of a small island house as they waited in suspended agony to decide their fate. Yet, here I was in a room with the Campidoglio silhouetted in the window, listening to church bells from a half-dozen churches, a pope across the river, the Temple of the Vestal Virgins in plain sight, and myself, a writer who had lost his bearings and his way with three beloved characters awaiting a salvation he could not think how to grant them. It felt more like paralysis than a lack of imagination. I called my aunt from Rome, and she made me feel better by saying her recovery was going fine. “I’m a mountain woman, Pat. And we’re tough old broads. Always remember that.” I remembered it, and I combed through all my journals looking for help or inspiration and thinking that I should start over and forget about the giant Callanwolde, the rape of my aunt, and the Wingo family. Write a modern novel, I told myself, where not a single thing of interest happens, where all suffering is internal and existential and without consequence. I had run into a complete breakdown of language, and for a week I suffered and did not write a word.

Then, the life I was in the middle of living sent me a sign out of nowhere – nowhere being the native country of the novelist. I had a night where Rome gave me an impermeable lesson in how a novelist’s mind works.

At Newsweek magazine in Rome, a new bureau chief had arrived after being evicted by the Communist government of Poland for his explosive articles on the Solidarity Movement led by Lech Walesa. His name was Andy Nagorski, and he and his beautiful wife, Krisha, had lived in temporary housing near us. We had become fast and instant friends. Both were lively, opinionated, and blazing with a fiery zeal for the freedom movement that was taking place all over Poland at that very moment. After they settled in to their busy social life in Rome, the Nagorskis invited us to their new home overlooking the incomparable Piazza Navona. I stood in a window with a glass of Pinot Grigio and looked down at the most spectacular piazza in Europe, trying to memorize every delicious detail of Bernini’s fountain below me and the lush expectancy and laughter of the Roman crowd, who never tires of its city’s irresistible allure. There were acrobats, and sword-swallowers, and accordion players, and mimes, brilliant with their stillness. Andy came to get me and introduced me to an Italian senator. The members of the dinner party were all attractive and flamboyant in a sophisticated, unconscious way. Lost in the evening, I forgot about my novel and I abandoned the stricken Wingo family, and left them to their own devices. Then Krisha Nagorski summoned us to the feast she had prepared. I would have recorded that meal in all its delicious plenitude except for what happened next.

On a couple of nights in your life, a writer can catch sheet lightning in a perfume bottle – if you are lucky and if you are ready. I held the chair for a dazzling Italian woman who looked and moved like a theater actress. When Italian women are beautiful in a certain way, they look as though they were spun from threads of gold and Venetian glass and snow melting into Lake Como. Her dress was silk, and her figure divine, and she spoke English with fluency and wit. We liked each other immediately, and we got lost in conversation from the antipasto to the dessert. Finally, she surprised me by asking me a loaded question. “Why have you not asked me the most important question, Pat? And the most obvious one?”

“What question would that be?” I asked.

“Surely, you’ve noticed that I am missing my left arm?” she asked.

“Of course I did,” I said. “But I was raised in the southern part of America and it would be considered rude for me to have mentioned it before you did.”

“On the contrary, it would be most natural,” she said. Her empty silken sleeve was pinned with great artistry to her comely dress. “It is the most striking thing about me, don’t you think?”

“No, you’re one of the loveliest women on earth. That is the most striking thing about you.”

“Ah! Your novels must be very romantic. Would you like to hear how I lost my arm?”

“Very much, if you wish to tell me,” I replied.

“I am a passionate animal lover. I’ve been to Africa on safari many times. I have photographed the great cats and watched the migration of the wildebeest on the Serengeti Plain. Several years ago, I was visiting the zoo in Rome – an appalling place.”

“Terrible,” I agreed.

“I was wandering through the exhibits when I saw a worker torturing a full-grown tiger with a hoe. It enraged me so much that I went over the barrier and attacked the man with both fists. Of course, the tiger did not understand that I was his rescuer. He tore my arm off at the shoulder, and I almost died on the operating table that night.”

“I didn’t know a tiger was that strong,” I said in disbelief. Now everyone at the table sat mesmerized by the woman’s story.

“In Bengali, tigers have killed full-grown men, then leapt six-foot fences with their prey in their jaws.”

Then it hit me all at once. I remembered the raped and beaten Wingo family, my aunt in Atlanta, the bearded giant who came during the Korean War. It began to coalesce around me, dizzyingly, all-powerful, overwhelming. I had forgotten about filling my tank up with gas in Columbia so long ago and throwing chicken necks into the cage of Happy the Tiger. I remembered Uncle Joe and his money-making schemes and the shrimper Henry Wingo buying a tiger for his Esso station. I looked over at my wife, who knew I had no idea how to rescue the Wingo family after they had been torn apart by a luckless fate and the appearance of three ex-convicts into their lives.

“Lenore,” I said to my wife, “I have a Bengal tiger living in the Wingo’s backyard.”

“I don’t understand,” she said.

“I’ve got a terrible surprise for the goddamn men who raped my family. Let’s see how they do against a Bengal tiger.”

“I don’t understand,” the lovely one-armed Italian woman said.

“Tonight, signora, I owe you the whole world,” I said. “You just presented me with the gift of my own novel.”

“I still do not understand,” she said.

“A gas station in South Carolina… a dinner above the Piazza in Rome. You’ve got to keep journals. You’ve got to write everything down.”

Happy the Tiger saved my novel, and what a golden world a novelist lives in when there is a tiger at an Esso gas station.