Food & Drink

The Most Delicious Suburbs in America

Just outside New Orleans proper, Metairie, Chalmette, Gretna, and other suburbs offer a world of sublime tastes, from spit-roasted lechón to Creole Italian classics to the po’boys of your dreams

Photo: Cedric Angeles

Chopping lechón at Cebu Litson & Grill.

The first meal I ever ate in New Orleans was not in New Orleans at all. It was in Metairie, a suburb that lies between the New Orleans airport and the city itself. It was my first visit from New York, and I had done my research, which in those still-rudimentary-internet days meant having somebody mail me a physical copy of the Times-Picayune’s annual restaurant guide. In it, I read a description of the charbroiled oysters at Drago’s, the seafood restaurant opened in Metairie by a Croatian immigrant named Drago Cvitanovich and his wife, Klara, in 1971: how fat Gulf oysters were set atop a blazing grill, basted with garlic butter, and then allowed to poach in the mingled fat, smoke, and brine beneath a bubbling crust of Parmesan and Romano. I did not need to read this twice. I stepped off the plane and piloted my rental car not toward the narrow streets and Spanish balconies of the French Quarter, but to the strip-mall-and-chain-restaurant-lined blacktop of Veterans Memorial Boulevard.

I have never regretted that those oysters were my first taste of what would eventually become my home. Even less so over the past decade, when many suburbs, looked down upon for so long as cultural wastelands, have come to be recognized as some of the most exciting places to eat in America. In the South, that’s meant cruising Atlanta’s Buford Highway in search of immigrant cooking from every corner of the globe; it’s meant noshing the length of Nolensville Pike, as it zags appetizingly south from downtown Nashville; it’s meant getting lost in the deliriously sprawling outskirts of Houston.

What it hasn’t generally meant is forsaking the famously abundant culinary pleasures of New Orleans proper to explore its suburban precincts. There may have been a few destinations alluring enough to draw tourists and locals across the parish line: Drago’s; Mosca’s, the storied Italian restaurant in an unassuming white shack in Westwego, about a thirty-minute drive across the bayou; a handful of famed Vietnamese restaurants; maybe Rocky & Carlo’s, over in Chalmette, with its bricks of baked macaroni and sign reading LADIES INVITED. For the most part, though, New Orleans’ burbs lagged behind those of other cities.

That’s rapidly changed. There are really two stories that make New Orleans’ suburbs worthy of serious culinary exploration. One is the critical mass of immigrant restaurants that has finally allowed them to catch up with other burbs across the South. The other is a unique set of historical and social circumstances that has resulted in a curious truth: Some of the most classically New Orleans food in New Orleans lies outside the city limits.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Fried yuca and chicharrones at Mawí Tortillas; a fried shrimp po’boy and a cup of gumbo at Radosta’s; grilled chicken-and-sausage jambalaya at Chicken’s Kitchen.

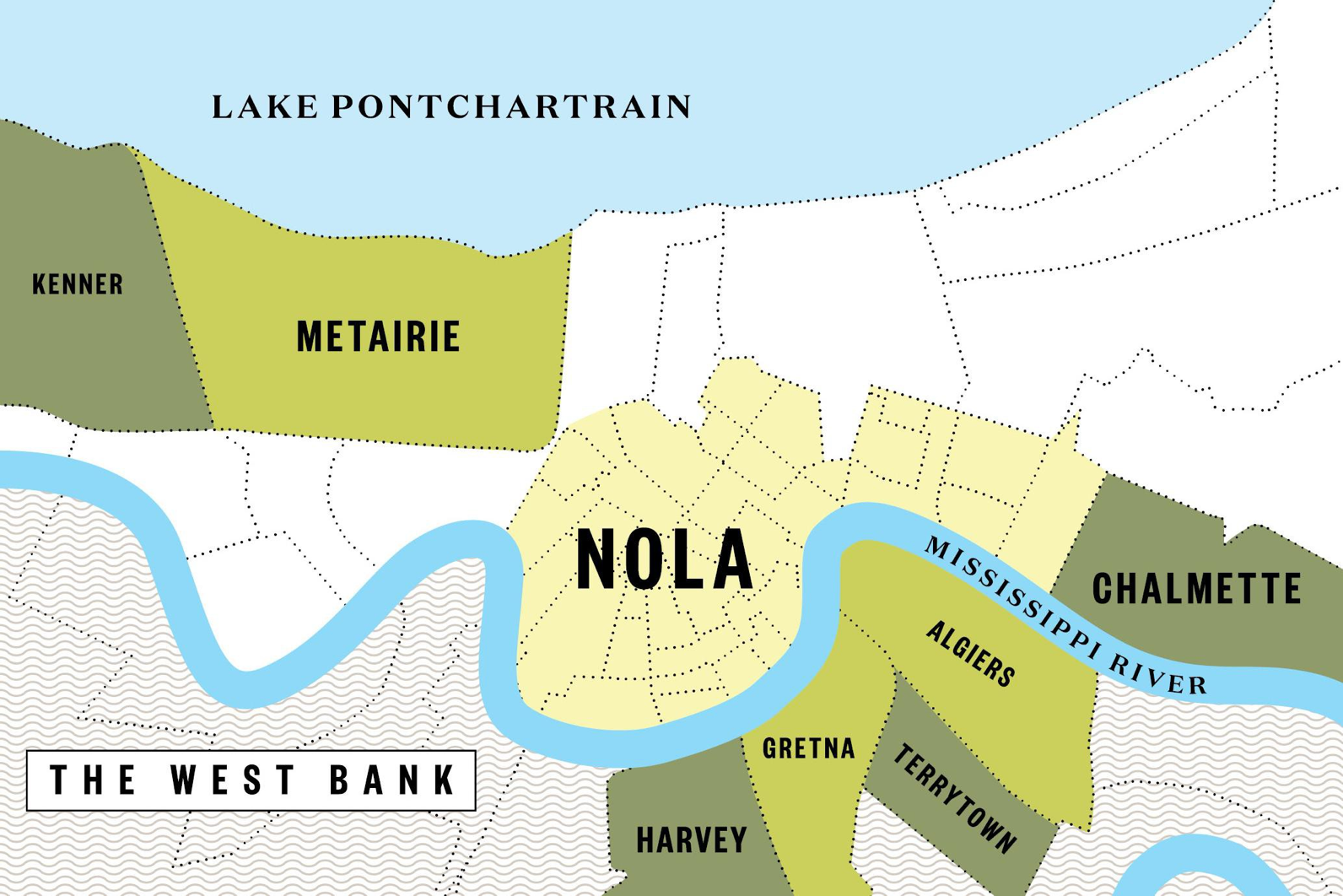

For purposes of orientation: I’m talking here about three main zones, all within a thirty-minute drive of downtown. There’s Metairie and its western neighbor, Kenner, which is home to Williams Boulevard, perhaps the single most diverse strip of dining in the metro area. On the other side of the city, there are the traditionally working-class downriver precincts of St. Bernard Parish. And then, across the Mississippi, there’s the West Bank (New Orleans being a complicated place, it’s sometimes styled as Westbank, and also, it’s not really west), home to a cluster of communities including Algiers (which is technically part of New Orleans) and Gretna.

None of these, I warn you, are the kind of suburbs you call “leafy.” They are, for the most part, flat and hot. You need to have a taste for empty crossroads, deserts of parking lots, left turn lanes. Streetcars, beignets, and brass bands this ain’t.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Tia and Marlon Chukumerije; the kitchen crew at Radosta’s.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Joe Impastato; Wilfredo Avelar; Loy Madrigal.

But let’s take a drive. On the West Bank, we can start in Algiers, where you might catch Loy Madrigal in the driveway of his restaurant, Cebu Litson & Grill, preparing a naturally raised Mississippi hog that he stuffs with lemongrass, ginger, and other aromatics and rubs in soy sauce to spit-roast for lechón, the specialty of the Filipino province Cebu, where he was born. His wife, Iris, is in charge of tending the pig, and inside the restaurant, located in a residential-looking building, she may be rolling long, tightly wrapped lumpia, stuffed with pork and vegetables, while other homestyle Filipino dishes bubble on the stove. Though famously stressful, running a restaurant is most likely a relief from Madrigal’s former life as a professional bodyguard and head of security for Cebu. Since opening in May 2020, his business has become a hub for a local Filipino community that has had a presence in the area since the 1700s.

But pace yourself. We have ground to cover. Staying on the West Bank, we’ll grab some Haitian soup joumou at Rendez-Vous Créole, in Algiers, then pop over the Jefferson Parish line into Terrytown for overstuffed banh mi at the back of Hong Kong Food Market; then a quick stop at Sultan’s Shawarma Shack, located inside a onetime Rally’s in Gretna, for frozen mint lemonade so loamy and herbal it feels as if you’ve run your tongue through a mint patch. And, before getting on the bridge back to the city, we can make a final stop at TD Seafood and Pho House for Vietnamese crawfish, doused with garlic and butter, and a bowl of bun bo hue. The restaurant, in Harvey, serves an “evil” version of that dank and satisfying soup, pumped up with an alleged thirteen million Scoville units’ worth of chile. If you finish it, you get your photo on a wall of fame. But really, we already deserve a medal for the day’s eating, I’d say—no extra pain required.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: A bowl of pochero, with custom-cut beef shank and vegetables; noodles with pork and vegetables on the stove at Cebu Litson & Grill.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Madrigal in Cebu’s kitchen; a platter of pork dishes; a lunch table of Cebu regulars.

Spiciness was the first—and, for a long time, the only—thing I heard people mention about Secret Thai Restaurant when it opened in Chalmette, in St. Bernard Parish, in 2018. It offers its Bangkok-style dishes on a heat scale of 1 to 5, corresponding to the number of teaspoons of Thai chile added. One teaspoon is more than most people can take; the staff will actively try to talk you out of anything over two. While there are a few regulars who are allowed to order level 5, they’ve had to demonstrate that they wouldn’t either die or sue. “We know all of our fives by name,” says Siamrath “Sam” Boonsakul, whose mother, Panlada Ten, is the owner and chef of the family-run business. (For the record, I am fairly spice tolerant and order a 0.5.)

But all of this fixation on capsicum threatens to obscure the fact that Secret Thai serves a bold, complex strain of Thai cuisine found almost nowhere else in the area. I fell for it the moment I noticed that Ten cuts the corners off her Styrofoam to-go containers when they hold fried dishes, a small but rare expression of care that ensures the contents don’t steam and grow soggy on the way home. This comes in handy for the dish pad gang daeng, which consists of white-fleshed fish encased in a crackling crust over which you spoon a magnificently funky curry of eggplant, preferably saving enough of the jammy sauce to moisten a gigantic order of crab fried rice.

Boonsakul says his family knew little about the geography of New Orleans when they went looking for a location after moving from Los Angeles. Chalmette, after all, showed up as just a few miles from downtown. “We didn’t realize that a three-minute drive across a little bridge could be such a different culture,” he says. But they have grown to appreciate what the suburbs have to offer: lower rent, more space, quicker permitting, a community of familiar faces. At the same time, social media, and a generation accustomed to using it to seek out the best eating, ensures a steady flow of pilgrims.

Wilfredo Avelar, of Mawí Tortillas, echoes those sentiments. His restaurant shares a somewhat run-down strip mall in Metairie with a Subway, a hair salon, and a ballroom dancing studio. There was mild shock, in 2019, when Avelar chose these digs over his previous job, as the precocious young executive chef of Emeril Lagasse’s restaurant Meril. There, his menu included rock shrimp tacos served on corn tortillas; when the tortilleria that produced those tortillas went out of business, Avelar and his father, Carlos, who emigrated to the United States from El Salvador in 1974, decided to take over the business. In the beginning, they kept it wholesale, providing tortillas for a mix of local Hispanic spots and higher-end restaurants in the city, all made from a traditional, clattery old metal machine located in the center of the small storefront. But Avelar couldn’t quite stay away from the stove and began offering pupusas on weekends. On Tuesdays, he introduced his version of quesabirria tacos, the wildly popular style of tacos filled with stewed and shredded meat (in this case brisket), topped with cheese, grilled until crisp, and served with a cup of the meat broth. By the time the pandemic arrived—making selling to restaurants about the only business less stable than being a restaurant— Mawí was primed to pivot to full-time meal service.

Avelar’s birria leans more Louisianan than traditional versions, with more garlic and bell pepper, less cinnamon and clove. It may be the big seller, but I can’t stay away from his version of chicharron and yuca, a rich and rustic dish found across Central America to which Avelar adds just a touch of his past life, a bright cabbage slaw and a streak of creamy Honduran aderezo. “You go through working for Emeril for fifteen years and you have to add something fresh to everything,” he says.

The entire New Orleans metropolitan area, particularly its suburbs, has become dramatically more Hispanic in the past two decades, with populations doubling almost across the board. The region has long been home to one of the country’s largest Honduran American communities—a vestige of United Fruit Company’s footprint—but it was the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, that fueled an influx of Mexicans and Central Americans, many to work in reconstructing the city. For Avelar, that’s helped provide the opportunity to serve neighbors instead of waves of conventioneers. “In New Orleans we used to say that summer was for the locals, when there weren’t so many tourists around,” he says. “Out here, it’s like it’s always summer.”

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Quesabirria tacos at Mawí Tortillas; Cilantro garnishes the yuca and chicharrones.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: Avelar with his father, Carlos; fresh tortillas.

How the suburbs became the repository for a strain of New Orleans cuisine that has steadily dwindled in the city proper is a tale of two demographic tides: The first is the one that saw massive numbers of white people abandoning cities across America throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. There was, of course, a racial component to the shift; Metairie may be most known for having been the home base of David Duke. But this was also the era of the Suburban Dream. “These people saw modernity,” says Justin A. Nystrom, of the largely Sicilian New Orleans population he writes about in his book, Creole Italian. “These houses had yards. They had three bedrooms. They had open layouts!”

In any event, the exodus was so dramatic—the percentage of whites in the city dropped from 63 to 35 percent between 1960 and 1990—that it essentially created a suburban shadow city, complete with Metairie’s own version of Bourbon Street in the nightclub district called Fat City. And it’s no surprise that the new suburbanites brought their famously passionate foodways with them.

If that is the force that carried po’boys and gumbo and Creole Italian restaurants out to the suburbs, its tidal counterpart was gentrification, which swept the professional and creative classes back into the city after Katrina. This, too, reflected a nationwide trend, the so-called Great Inversion. The new urbanites weren’t necessarily in search of traditional New Orleans cuisine. For much of the past decade, two of the hottest restaurants in New Orleans (Shaya and chef Alon Shaya’s follow-up, Saba) have been most famous for their hummus.

And so, you have beautifully preserved jewels like Radosta’s Restaurant, in Old Metairie, a third-generation Italian grocery store that, over the course of forty-seven years, has gradually morphed into the po’boy shop of your dreams. Such a family business is Radosta’s that it shuts down when the Radostas themselves—brothers Don, Wayne, and Mark, and their wives—go on vacation. Wayne has long been in charge of making the homemade Italian and hot sausages and the roast beef. Don handles the red gravy (i.e., sauce) for the meatball and veal parmigiana po’boys. Grab a Barq’s root beer out of the cooler and some Zapp’s potato chips—it’s all on the honor system—and you’ve got as classic a New Orleans lunch as exists anywhere.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: A fried shrimp and roast beef po’boy at Radosta’s; Don Radosta; inside the third-generation Italian grocery store and restaurant.

Don Radosta’s red gravy is one manifestation of that Creole Italian culture, too infrequently recognized by outsiders as a pillar of New Orleans cuisine. There can be no better example of the form, in all its amber-preserved glory, than Impastato’s Restaurant. Joe Impastato was already a longtime veteran of French Quarter Italian restaurants when he and his wife, Mica, opened their own place, in Fat City, in 1979. Seemingly little has changed since then, including Impastato himself, who, at eighty-three, still regularly presides over both kitchen and dining room. You could describe the restaurant as a jewel box, if every facet of the jewels were a framed piece of football memorabilia. Jerseys cover nearly every surface, including the small stage where a crooner performs on weekdays.

The menu, too, is a time machine of delicacies fast disappearing in more modern precincts: spidini, for which thin strips of pork are wrapped around seasoned stuffing; brucciloni, similarly stuffed rolls of veal, long-stewed in red gravy; veal or fish “Marianna,” topped with artichoke hearts and mushrooms, named for Impastato’s mother, and a reminder that there is a space in heaven reserved for sauces that are equally applicable to fish or veal. Another in the genre is a concoction of lemon, butter, sherry, crabmeat, and shrimp known as Payton, after erstwhile Saints head coach Sean Payton. Impastato is such a die-hard Who Dat that he owns a Super Bowl ring from the Saints’ championship in 2010. Should any future coach get a dish, it will be a different one. Payton gets to keep his, no matter where he may end up. “He gave us a good fifteen years,” Impastato says. “He deserves it.”

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: “Rickey Jackson’s Crab Fingers,” a dish at Impastato’s named for the former Saints player; Impastato with a small sampling of his football memorabilia.

And then there are some places in the suburbs that make you wonder why anybody would ever want to move into the city. I feel that way about Chicken’s Kitchen, which you can find by looking for the line stretching daily down an otherwise residential block in Gretna, on the West Bank. “Big Fat Chicken” is the childhood nickname of Marlon Chukumerije, a genial thirty-three-year-old with thin dreadlocks who wisely dropped the first part when he opened his modern soul-food meat-and-three in 2020. He had previously worked in construction before starting a catering business in 2014, including an annual “Lemonade Day” on the first Saturday in May, for which he and his four sons served refreshments and hot plates from his driveway. When Lemonade Day rolled around during the first year of the pandemic, Chukumerije says, there were eighty cars lined up, two hours in advance. “It was almost stupid not to open a restaurant,” he says.

The lines—fueled by a savvy social media presence—have never gone away. Most days, you line up on Derbigny Street, inch your way up to the door, then along a wall covered with promotions for local Black-owned businesses, and finally to the steam tables at which Chukumerije has built a different menu for each day of the week: Monday is for red beans (naturally) and crackling fried chicken; Tuesday, seafood-smothered okra and stuffed Cornish hens; and so on to FRYday, when the stars are extraordinary deep-fried ribs, which he treats like tiny, succulent country-fried pork chops. I am told that the first Tuesday of every month brings stewed oxtails, though I cannot personally vouch for this, since I have never gotten to Chicken’s in time to taste any; once, I got a message they were sold out before I even reached the bridge.

For Chukumerije and his wife, Tia, staying in Gretna is not only an economic decision but a point of pride. “First, my customer base is here,” he says. “Second, we don’t have that many locally owned businesses here, especially places doing home-cooked meals, using fresh vegetables.” The relative affordability of staying outside the city also allows him to keep prices low, portions big, and his staff, many of them childhood friends, happy and loyal. The entire restaurant closes once every three months for a mental health week.

Meanwhile, several years had passed since I had Drago’s charbroiled oysters. When I stopped in, it all came back: the walls of flame springing up as cooks poured butter over the oysters, the bubbling cheese, the smell of smoke drifting across the restaurant. A couple came in, carting roller bags, and I wondered if they were pulling the same trick of coming straight from the airport that I used to. Truth be told, the oysters have been available for a few years in downtown New Orleans, where Drago’s opened a branch at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside, but I never go there. Somehow, they just taste better in Metairie.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

From left: The Chukumerijes in the kitchen; deep-fried ribs with mac and cheese, candied green beans, and king cake bread pudding at Chicken’s Kitchen.