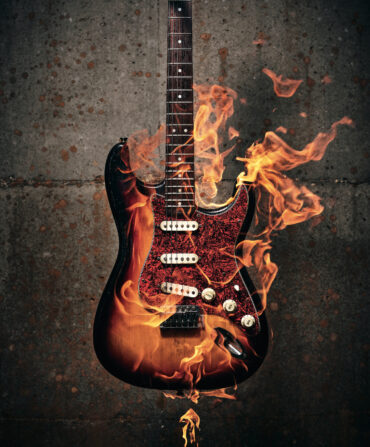

Music

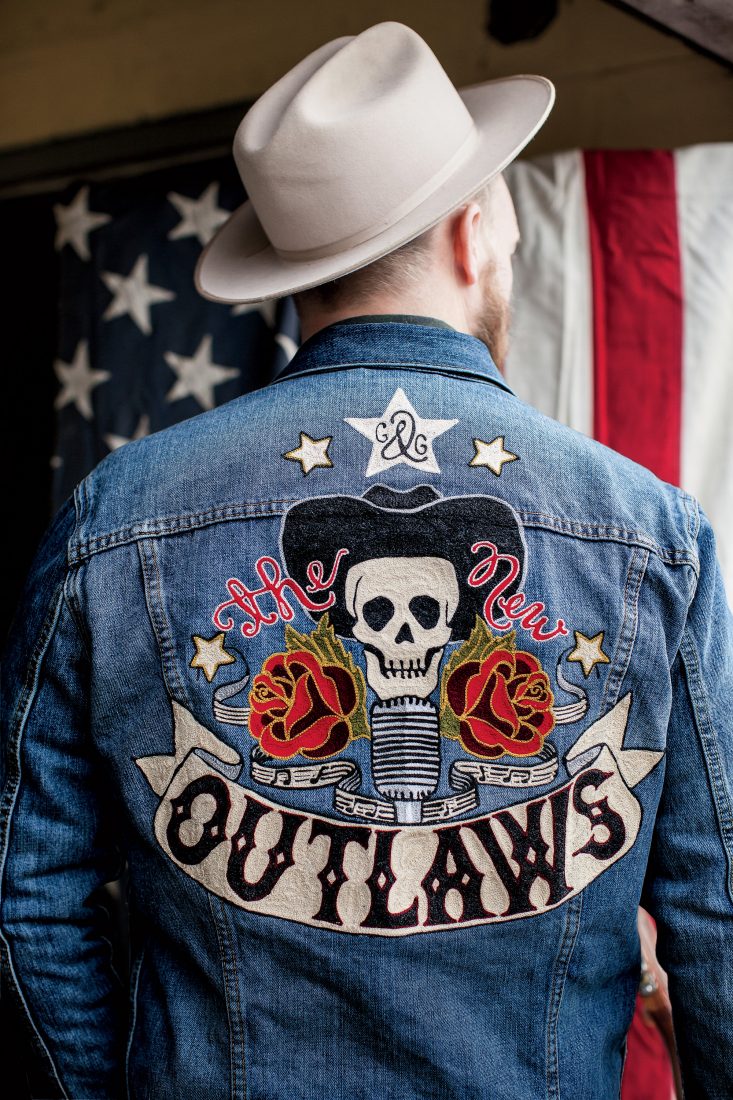

The New Outlaws: Young Guns

A dozen rising acts shaking up the country scene

Photo: Gately Williams

Although she comes from notable country music lineage—she’s the daughter of singer-songwriters Lee Ann Womack and Jason Sellers—Aubrie Sellers soaked up a rock-and-roll vibe hanging out as a kid at Nashville skateboarding parks, checking out shows at rock clubs, and developing an obsession with Led Zeppelin. “‘When the Levee Breaks’ is one of my favorite songs of all time,” she says. “When I discovered that, it was life changing.”

That influence bleeds into her debut, New City Blues, a blistering set of “garage country”—as she calls it—without an acoustic guitar to be found. The album opens with forty-five seconds of sinister reverb-soaked guitar before segueing into the bruising thump of “Light of Day.” It’s a brash, bold sound that has made her one of Nashville’s most electric acts. “There ain’t no map for the road I’m on,” she sings. Luckily for us, she’s finding her own path.

Photo: Miller Mobley

Eye Opener

Singer-songwriter Aubrie Sellers brings hard-charging country sizzle to her debut, New City Blues.

Parker Millsap

Don’t let the Leonardo DiCaprio looks fool you. Behind that boyish face is a twenty-three-year-old dynamo with serious songwriting chops and a voice that ranges from a greasy howl to an angelic falsetto. The Purcell, Oklahoma, native’s songs on his new album, The Very Last Day, are intimate and vivid, diving deep into sin and spirituality and inhabiting conflicted characters dealing with life-altering choices. “Heaven Sent” is a devastating tale of a gay son asking his evangelical father for acceptance, while “Hades Pleads” is a twisted come-hither to a girl courted by the Greek god of the underworld. Onstage, Millsap has the charisma of Elvis (the young version) and a crack backing band featuring string player Daniel Foulks and bassist Michael Rose, Millsap’s best friend since the eighth grade. His shows are positively riveting, at times acerbic, but loaded with a charisma that very few artists share.

Photo: Laura Partain

For years, Margo Price couldn’t get producers to listen to her. A fixture in the East Nashville music scene, Price had to hock her wedding ring, some vintage recording equipment, and a car she and her husband shared to self-finance the recording of her brand-new debut, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter. Most Music City bigwigs passed on it, but a friend mentioned it to Jack White, who quickly signed her—the first country artist on his Third Man Records. It’s a spot of good fortune at the end of a chapter of Price’s life with way more downs than ups. She and her husband lost a son two weeks after birth, a former manager ran off with most of her money, and she spent time in the Davidson County jail after, she says, “running around with the wrong crowd late at night.” That stint behind bars spurred a creative streak during which she wrote one of the album’s highlights, “Weekender.” “I snuck a piece of paper and pencil up into my cell and started writing,” she recalls. The rest of the album is as lyrically gritty as her voice is piercing. “Hurtin’ (On the Bottle)” is a late-night tale of self-medicating after a nasty breakup, while “About to Find Out” finds her fixing for a fight with an unnamed nemesis. Already, she’s been dubbed the new Loretta Lynn. “I love her and it’s flattering, but I’ve worked long and hard to be my own artist,” Price says. And now that her uncompromising attitude has finally paid dividends, it’s given her the chance to rectify certain wrongs: “My husband was able to buy my wedding ring back,” she says. “That was the only thing I was sentimental about.”

“If you get to know me, you won’t think I’m much of an outlaw,” says Andrew Combs, laughing. True, Combs—a Dallas native and now a Nashville resident—might not travel in the grit-’n’-spit vein of country music. But his breezy melancholia on his second album, All These Dreams, is as impactful as it is elegant, reminiscent of the best of 1960s Laurel Canyon folk à la Jackson Browne along with his idols, the 1970s Texas troubadours Guy Clark and Kris Kristofferson. As Combs spins tales of love and loss, his vocals are an expressive murmur while steel guitar and piano swirl around him. But the album is no downer. Songs like “Pearl” look for the sliver of good in a bleak situation. “I like sad songs, and I always have,” he says. “But it’s just as important to put stuff in there to give some sense of hope.”

Photo: Madison Melissa Fuller

andrew_combs_PC-Madison_Melissa_Fuller

Let’s get this out of the way: Brandy Clark is currently the best songwriter in Nashville. Whether she’s penning hits for Miranda Lambert and Kacey Musgraves or crafting effortless yarns for herself, she is as deft a wordsmith as Music City has seen and the rare mainstream force who rises above clichés. Her upcoming second album, Big Day in a Small Town (due out in June), has the same biting wit as her 2013 debut, 12 Stories, but it’s an even richer collection of songs, with a life-in-the-middle-of-nowhere thread running through the album. “There ain’t no mall/no Waffle House/but there’s always something to talk about around here,” she sings on the title track. Clark grew up in rural Washington State, and the album was influenced by a return visit after her father’s death. “There were so many people at his memorial that it had to be held in the high school gymnasium,” she says. “That doesn’t happen elsewhere unless you’re famous.” Clark’s particular gift is writing detailed lyrics that still allow listeners to connect them with their own mistakes, victories, or the frustrations of just trying to get by. “Sometimes I go to the bank in the morning before I start writing,” she says. “And I see the girls working behind the counter and I wonder, what are their lives like?”

Let’s get this out of the way: Brandy Clark is currently the best songwriter in Nashville. Whether she’s penning hits for Miranda Lambert and Kacey Musgraves or crafting effortless yarns for herself, she is as deft a wordsmith as Music City has seen and the rare mainstream force who rises above clichés. Her upcoming second album, Big Day in a Small Town (due out in June), has the same biting wit as her 2013 debut, 12 Stories, but it’s an even richer collection of songs, with a life-in-the-middle-of-nowhere thread running through the album. “There ain’t no mall/no Waffle House/but there’s always something to talk about around here,” she sings on the title track. Clark grew up in rural Washington State, and the album was influenced by a return visit after her father’s death. “There were so many people at his memorial that it had to be held in the high school gymnasium,” she says. “That doesn’t happen elsewhere unless you’re famous.” Clark’s particular gift is writing detailed lyrics that still allow listeners to connect them with their own mistakes, victories, or the frustrations of just trying to get by. “Sometimes I go to the bank in the morning before I start writing,” she says. “And I see the girls working behind the counter and I wonder, what are their lives like?”

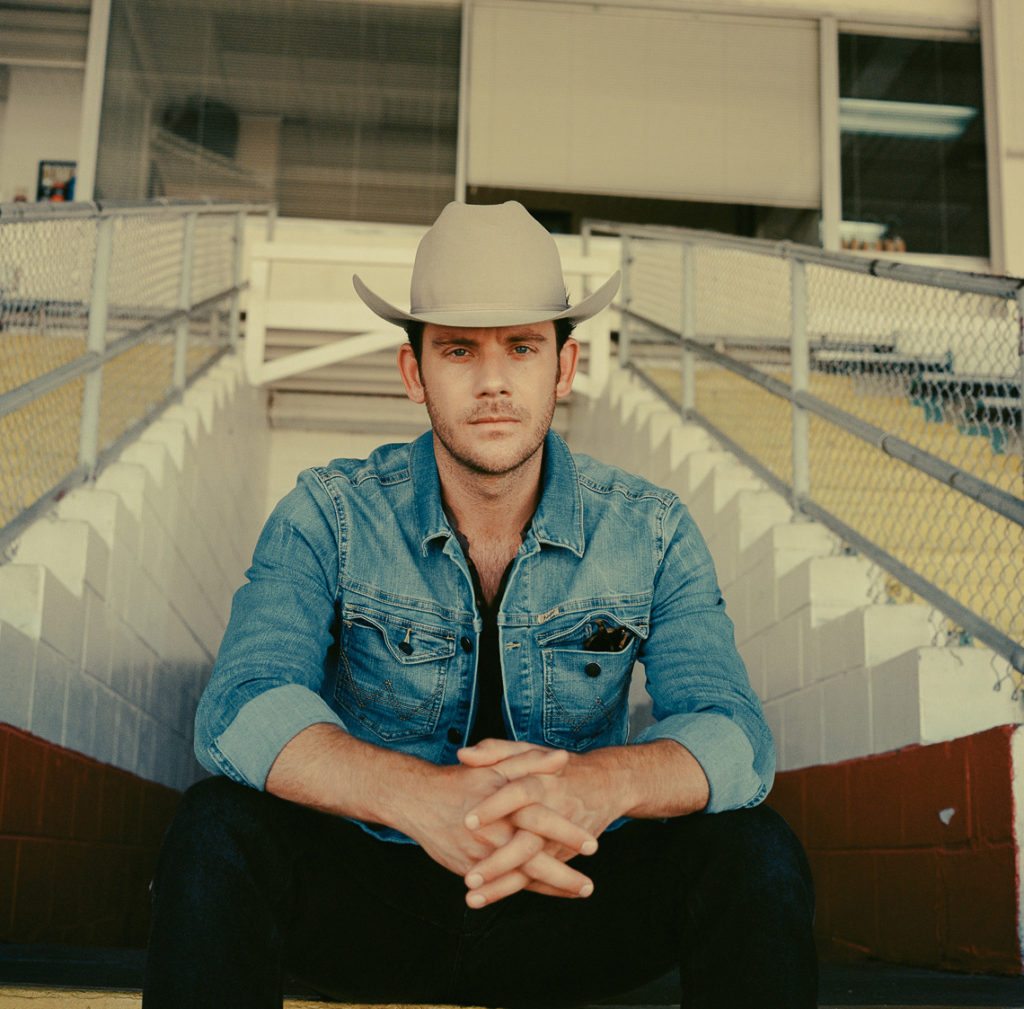

He looks a bit like the late, great Hank Williams, and he sounds like a young Townes Van Zandt, but Cale Tyson is his own man. The twenty-five-year-old from Cleburne, Texas, isn’t the first skinny kid to wear a cowboy hat and a pearl-snap shirt in tribute to the giants of vintage country, but he is one of just a few whose lovesick blues actually sound like they come from the heart. Tyson’s 2014 EP, Cheater’s Wine, is a collection of boot-gazing, slow-burning ballads with such throwback titles as “Fool of the Year” and “Dreams Don’t Come True.” “Emulating is a big part of learning how to write a song,” he says. “At first, I was just trying to copy what I’d heard. As I went along, my songs started growing to where I could say, ‘Yeah, that’s my style.’”

He’s now working on his first full-length album, and like his predecessors, he goes over as well in municipal auditoriums as he does in hipper hangouts. “When we play in smaller towns, everybody usually comes out, from the teenagers to the grandpas,” Tyson says. “I think a lot of people just don’t have the energy to scope out artists who aren’t on the radio, but after we play, they’ll be like, ‘Damn. You guys were awesome.’”

Photo: Joshua Black Wilkins

Cowboy Cool

Texan Cale Tyson embraces an old-country sound.

Whitey Morgan’s grandfather William Morgan moved to Flint, Michigan, from Glens Fork, Kentucky, to work in an auto plant. His dad became an autoworker, too, along with “all my uncles, and everybody else’s dads,” Morgan says. “By the time I was old enough to get a job, everything was shutting down.” His late grandfather instilled more than just his work ethic.

Whitey Morgan’s grandfather William Morgan moved to Flint, Michigan, from Glens Fork, Kentucky, to work in an auto plant. His dad became an autoworker, too, along with “all my uncles, and everybody else’s dads,” Morgan says. “By the time I was old enough to get a job, everything was shutting down.” His late grandfather instilled more than just his work ethic.  He left his grandson a guitar and a collection of country records that inspired the hard-driving sounds of a working-class outlaw. “Detroit is known for its loud, obnoxious rock bands, and we are definitely louder than most country acts,” Morgan says. Whiskey-soaked anthems like “Ain’t Gonna Take It Anymore,” from 2015’s Sonic Ranch, are helping his fans loosen up at a time when good blue-collar jobs are scarcer than they’ve been in generations. “The whole point of our live show is to get people to stop thinking about their damn jobs for a night,” he says. “That’s what a lot of my songs are about: Forget all the bullshit and come have fun.”

He left his grandson a guitar and a collection of country records that inspired the hard-driving sounds of a working-class outlaw. “Detroit is known for its loud, obnoxious rock bands, and we are definitely louder than most country acts,” Morgan says. Whiskey-soaked anthems like “Ain’t Gonna Take It Anymore,” from 2015’s Sonic Ranch, are helping his fans loosen up at a time when good blue-collar jobs are scarcer than they’ve been in generations. “The whole point of our live show is to get people to stop thinking about their damn jobs for a night,” he says. “That’s what a lot of my songs are about: Forget all the bullshit and come have fun.”

At thirty-five, with a failed major-label deal and several critically acclaimed but little-known albums to her name, Lindi Ortega knows just how frustrating the music business can be. That hasn’t stopped the Canadian-born singer-songwriter from putting on her signature rockabilly makeup and lipstick-red cowboy boots and making some of the best music of her career. On her 2015 album, Faded Gloryville, she sits in on the lonely gigs and late-night woes of down-and-out musicians, plumbing the depths of disillusionment and despair with a voice as smooth as the slide guitar behind it.

Photo: David McClister

Long Black Veil

Nashville transplant Lindi Ortega played the Grand Ole Opry for the first time last November.

“People get down on their luck sometimes,” Ortega says. “Songs about being lonesome have always brought some comfort to me. It’s nice to hear when somebody else is feeling the same way.” It isn’t all gloom, though. Soulful organ riffs and swaggering brass keep her songs moving at a seventies-era clip. And Ortega is far from finished herself: She played the Grand Ole Opry for the first time last fall. “It was amazing,” she says. “I never thought I’d have the chance.”

With his long, greasy locks and thick-framed glasses, Aaron Lee Tasjan looks like that kid who was scribbling out poems in the back of the classroom while everybody else was getting excited about the homecoming game. But he doesn’t take himself too seriously when he’s picking out melodies on his guitar, singing songs with a wry wit rarely seen since the 1970s heyday of John Prine and Randy Newman. His 2015 release, In the Blazes, is a sly, smoke-clouded collection of songs that includes “Florida Man,” a cheer-up message for a state with a reputation problem, and “E.N.S.A.A.T” (East Nashville Song about a Train), a shrewd dig at a new wave of self-serious artists moving to the once under-the-radar neighborhood. It isn’t as harsh as it sounds: Tasjan lives there, too. “It’s a place like New York City used to be, where you can be an artist and not need to have a job on the side,” he says. “I love the scene here.”

With his long, greasy locks and thick-framed glasses, Aaron Lee Tasjan looks like that kid who was scribbling out poems in the back of the classroom while everybody else was getting excited about the homecoming game. But he doesn’t take himself too seriously when he’s picking out melodies on his guitar, singing songs with a wry wit rarely seen since the 1970s heyday of John Prine and Randy Newman. His 2015 release, In the Blazes, is a sly, smoke-clouded collection of songs that includes “Florida Man,” a cheer-up message for a state with a reputation problem, and “E.N.S.A.A.T” (East Nashville Song about a Train), a shrewd dig at a new wave of self-serious artists moving to the once under-the-radar neighborhood. It isn’t as harsh as it sounds: Tasjan lives there, too. “It’s a place like New York City used to be, where you can be an artist and not need to have a job on the side,” he says. “I love the scene here.”

Just two seconds into “Hello Miss Lonesome”—the lead track on Marlon Williams’s self-titled solo debut—the song explodes into a rollicking clip, the sound track to a late-night honky-tonk where the beer keeps flowing from a bottomless keg. But later on the album, Williams croons like Roy Orbison, with his aching, rich tenor showing no hint of his New Zealand accent. Wait, he’s a Kiwi? Yep, and proudly so, hailing from the tiny town of Lyttelton. While singing in his Catholic church choir as a teenager, Williams discovered his father’s collection of country albums and spent the next several years sharpening his craft and magnetic stage presence in both New Zealand and Australia, playing everything from Beatles covers to his own country laments. The twenty-five-year old will spend part of this year touring the United States, and while unsure of what to expect, he’s steady in his resolve to play his style of music. “I’m curious as to how American audiences will see my music on the spectrum of country,” he says. “But most of all I’m just excited to be back to grassroots touring. That’s what keeps you keen.”

Photo: Nato Welton

New Zealand-born Marlon Williams, photographed in London.

He grew up in San Diego and worked in advertising in Los Angeles until he was thirty-two. But Sam Outlaw’s output so far proves that you don’t need a smoke-scarred baritone or a drinking problem to write a heart-wrenching country song. And by the way: If you’re skeptical about California country, Merle Haggard and Dwight Yoakam would like to have a word with you. “I take some inspiration from the Bakersfield sound,” Outlaw says. “I also draw on the singer-songwriter tradition: Jackson Browne, the Eagles, James Taylor.” The gentle twang and wistful, sun-soaked lyrics on Angeleno, his 2015 major-label debut, would feel right at home on scratched vinyl or a road trip up the coast. And while he may not immediately live up to his grizzled stage name—Outlaw is his mother’s maiden name, in fact—after ditching a steady job at an age when most people have given up on their musical dreams, he is definitely doing this his own way.

These six keyed-up twentysomethings mix a hodgepodge of sounds. Sometimes it’s barroom country backed by a rogue kazoo, and other times it’s a chicken-picking version of slow-burning soul behind the Janis Joplin–esque wail of Mary Beth Richardson, who shares singing duties with banjo player Stephen Pierce and guitarist Corey Parsons. But they always leave it all on the stage. Birmingham, Alabama, taught them that. “I feel like there’s a lot more passion from musicians who come from smaller cities—a lot more drive,” Parsons says. “We have a rawer, grittier sound.” The band released its self-titled debut last year, with songs honed from years of relentless touring, riling up crowds with romps like “Waitin’” and “Cry Baby Cry.” “This is what we like to do,” Parsons says. “Steve and I have been trying to grab people’s attention since we were busking.” And they’re going to keep sweating it out until the whole world is watching.

Photo: David McClister

Wide-Open Country

The Birmingham-bred Banditos at their Nashville garage studio.