Land & Conservation

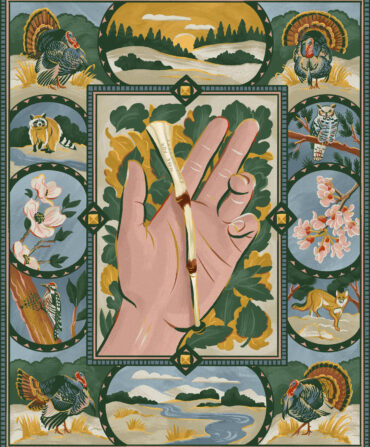

The Shell Hunter

For one Civil War relic collector, the past can be very much alive

Photo: Ben Gately Williams

The shell might have been a Christmas present from the Yankees. After midnight on December 25, 1863, five Union batteries commenced a yuletide rain of hellfire on Charleston, South Carolina, so relentless that, south of Broad Street, it was sometimes difficult to discern individual detonations. This particular mortar shell was a 100-pounder, shaped like a huge bullet and designed to fly nearly five miles at 900 feet per second out of the six-inch rifled barrel of a 12,000-pound cannon. Although some Parrott shells (named for their inventor, Robert Parker Parrott) were simply thick slugs of pure iron, this one contained a precise mixture of potassium nitrate, powdered charcoal, and sulfur known as black powder, designed to explode on impact. Many shells did just that. One that landed at 5 Beaufain Street instantly killed a slave named Rebecca. Another landed at the corner of Meeting and Market and blew off the leg of eighty-three-year-old William Knighton, who later died. Other shells did surprisingly little. “Most buried themselves harmlessly in the earth,” reported the Charleston Mercury. This shell likely left Morris Island on a high arc, screamed through the air, crashed through the roof of a carriage house on Tradd Street, and vanished.

“This house has been in my family for three generations,” says Simons Young, a Charleston architect who set to work restoring the property for his parents in 2010, nearly 150 years after that fateful Christmas. “It was built in 1774 by Judge Robert Pringle. The carriage house might even be older.” To fit a new HVAC system beneath the thick heart-pine joists of the carriage house floor, Young’s contractors started digging. Nearly five feet down, a worker clanged his shovel against a big, round object held firmly by sandy soil. Mistaking it for a chunk of concrete, he gave it several blows with a sledgehammer.

“My head contractor calls,” Young tells me, “and says, ‘Hey, man, you gotta get down here, we found something real interesting.’ They had this thing roped off. I had two thoughts: One, if we called the bomb squad, they would probably just detonate it. Two, Dad was really excited. He wanted to keep it. When my contractor told me he thought he could get it disarmed, I had no clue that was even possible.”

The contractor had never found a shell himself, but in a city that had endured a siege of a year and a half and the impact of more than 10,000 pieces of Union artillery, he knew this was no isolated discovery. He called on Civil War relic traders from Virginia to North Carolina to Mississippi and eventually learned whom he needed to contact to avoid two undesirable outcomes: having a law-enforcement explosive ordnance disposal (or EOD) unit destroy the old shell as a precaution; or keeping the shell around as an unusual souvenir that might someday, hypothetically, blow its owner or his property to smithereens. Folks in the know about such things refer to this person as the Big Iron Man.

Photo: Ben Gately Williams

The Big Iron Man uses a wire brush to polish a disarmed shell.

At this moment, the Big Iron Man, a friend of his, and I are standing on his deep-woods property, peering into an oaken barrel half filled with mosquito-wriggler-infested water. At the bottom lies a bullet-shaped object about eight inches long. He reaches in and lifts it with callused hands. “Once you dig ’em up, you have to immediately put them in water to keep them from corroding,” he drawls. “This one is a Yankee Hotchkiss shell. It was just dug up in a field not too far from here.”

The Big Iron Man is handsome in a real-life, Sam Elliott way. Tall and powerfully built, he has wavy, longish salt-and-pepper hair and a grizzled face whose lined tributaries bespeak years in the sun and mud of salt marshes. There aren’t many like him—hunters of Revolutionary War and Civil War relics who specialize in the disarming and preservation of live shells and cannonballs; outside of police or military EOD units, he reckons maybe ten or twelve are spread out below the Mason-Dixon. They are a fairly secretive lot. Not only do they not want to give away their hunting spots, but disarming shells is both legally questionable and dangerous as hell. He has agreed to speak with me on the condition that I refrain from revealing his name or exactly where he lives. After growing up in Charleston, he moved “off” (as Charlestonians put it) many years ago, to somewhere along an imaginary arc connecting North Carolina’s Fort Fisher, South Carolina’s Fort Sumter, and Georgia’s Fort Pulaski, in a moss-and-pine-shaded corner of the Lowcountry that he regards as just this side of heaven.

The mortar he holds is encrusted with a rime of dirt and rust. Someone brought it to his property in a deep, sand-filled chest. The shell is cast iron, lead banded, much heavier than it looks. Despite having been fired toward Confederate soldiers, it still contains its deadly marble-size lead balls and black powder. “It’s a common misconception that these things are dangerous just to handle,” he says. “But there’s nothing to worry about unless you do something stupid.” With that, he underhands the shell thirty feet into the air.

His friend and I scatter. But the shell lands with a thud and just sits there in silence. The Big Iron Man doubles over with laughter.

“There’s a myth that black powder gets more dangerous as it ages,” he says. “‘Oh, it’s just so unstable.’ Well, if that’s true, do you know how many people should be dead? Do you know how much unexploded ordnance there is around Mobile Bay, Fort Fisher, or under the parade grounds at Fort Sumter? Tens of thousands of shells are probably still buried between just those spots, and there are still shells just all over Charleston. If they’re as dangerous as they say, you ought to see tourists being blown into the air like that scene at the end of Blazing Saddles. I’ve had live shells dug up on farms with plow marks cut right through them. How many farmers have you heard of being blown up?”

Soon, he has scrubbed the shell down and carried it over to a peculiar contraption he built in this remote stretch of piney woods, far from prying eyes and spacious enough to contain any flying shrapnel. He bolts the shell to a stand and lowers it into a deep, water-filled pit dug into the earth beneath a fixed, vertical drill. Connecting the stand to the man are a pair of long, spindly steel arms—one controls a water jet, the other the drill press. The arms snake over the backup blast shield, a hulking, tail-finned automotive relic of the 1950s.

The fat drill bit spins very slowly, biting tiny shards from the shell. Even if relic shells usually aren’t hazardous to handle, heat and possible sparks from drilling can change the equation. Pure black powder ignites at around 572 degrees Fahrenheit, and after so many years, the stuff in this shell might have undergone any number of chemical changes, seeping into fissures and creating explosive pressurized gases. “If I have to disarm something,” he says, “I’m going to do it slowly and underwater.”

The deeper the bit spins, the heavier the sweat on the Big Iron Man’s brow. He’s maintained a light but firm pressure for fifteen minutes when, suddenly, his right arm relaxes and he breathes deeply. He’s broken through. The jet of water neutralizes the powder, but the stuff can be sticky, and when it dries, it’s still dangerous. So he’ll flush out the shell for a couple of hours.

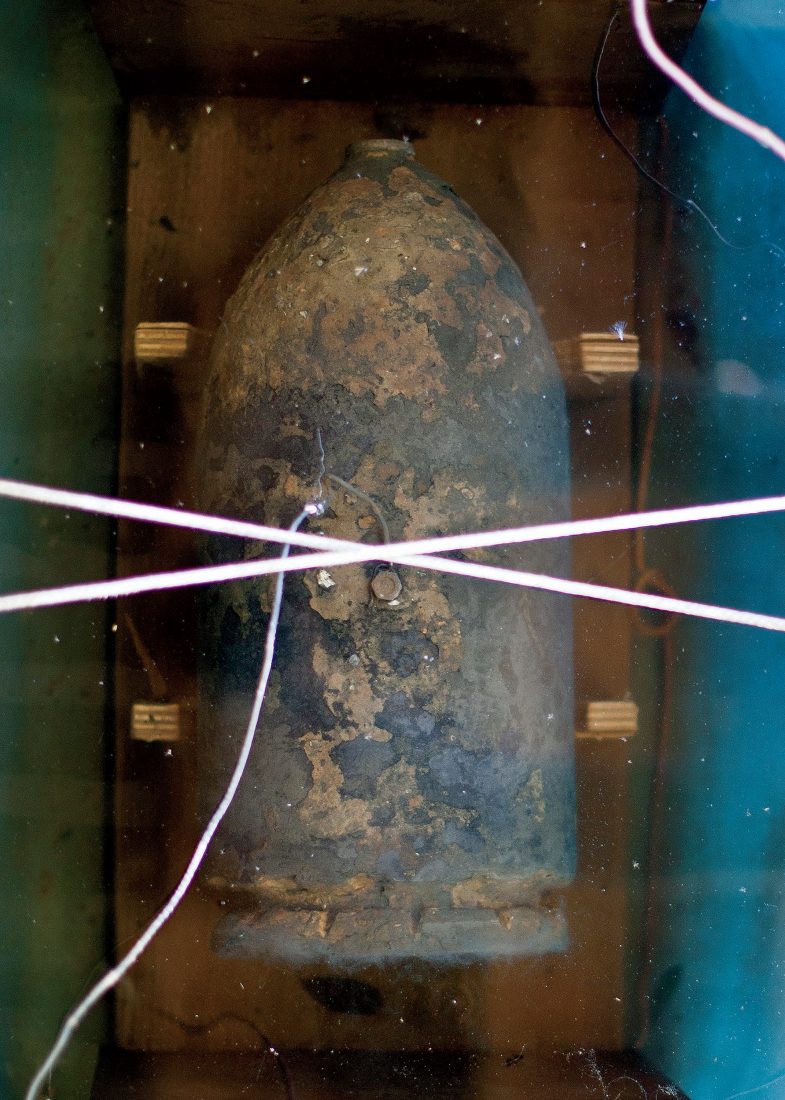

Photo: Ben Gately Williams

Shell Science

A shell underwater during electrolysis.

Once the shell is empty, he takes it from this remote site back to his house, hooks an electrode to its nose, fills a fifty-gallon barrel with water, and stirs in sodium carbonate, a chemical mostly used as a water-softening agent. This particular brand of alchemy is a crucial step for metal preservationists. The Big Iron Man probably has twenty disarmed shells—from twenty-pound Hotchkisses to beach-ball-size 300-pounders—in various stages of electrolysis. He learned the discipline from a Florida preservationist whose portfolio ranged from Fort Sumter cannons to the hull of the Titanic.

“Salt is the enemy of iron,” he explains. “It works its way in. Before electrolysis, I had drums of stuff we were finding. I tried coating the shells with wax that had a high melting temperature, because somebody said that would keep ’em from falling apart. But once those salts in the shells started to dry and expand, the shell would break right through that wax and disintegrate. It was heartbreaking.”

He flips a switch that sends a half amp of current into the barrel. Oxides and salts slowly bleed out into the clear water, as if the shell is smoking. For at least six months this electrochemical stew will leach out rust-creating molecules, leaving this small agent of death perfectly preserved and perfectly inert. “So that’s how it’s done,” he says. “If that shell had been picked up by any EOD unit, they would have just blown it up. To me and a lot of other people, that is simply destroying history.”

Which is why the Big Iron Man bothers with all this. Although some of the shells in his collection are worth thousands of dollars apiece, he assures me that he’s not much interested in money or publicity. He’s just sick and tired of hearing about pieces of American military history getting blown to bits.

Somehow or other, the Big Iron Man’s life has always included unexploded mortar shells. While he was growing up, they were a commonplace part of the landscape around Charleston. He and his friends would play hopscotch on old remnant shells strewn along the Battery. Walkways, church entryways, and flower gardens were lined with them. A pharmacy on Tradd Street used a massive solid shell called a “bolt” as a doorstop. “Sometimes they were live,” he says as we settle in comfortable chairs in his workshop, sipping Cokes his wife brought in as she joined our conversation. “Sometimes they weren’t. Eventually over time, folks just sort of picked them up, and there got to be less and less of them around.”

To this day, Charleston is almost certainly still littered with relic shells, although few remain in plain sight. “We were shelled for five-hundred-and-sixty-some-odd days,” Grahame Long, curator of history at the Charleston Museum, tells me after I’ve met the Big Iron Man. “The stuff turns up more here than anywhere in the South. We certainly haven’t found them all. And however many there are on the Charleston peninsula, there are, I’ll bet, ten times more in the harbor. Most of the EOD calls I’d hear about were coming from harbor dredgers. They’d be dumping spill out on Drum Island and the shells would just go down those dredge pipes like a big pinball.”

The Big Iron Boy learned about these artifacts scattered around his hometown while he was in elementary school. When he met Omega East, the late superintendent of Fort Sumter and longtime National Park Service historian, East regaled the youngster with stories of the fort’s battles—and the relics that still lay beneath the ground. A cheap metal detector led to a few discoveries, and soon he was hooked. As he pursued his new hobby, he learned early on how dangerous a Carolina marsh could be. “My younger brother and I went to this place one time when he was about eight years old and got split up,” he tells me. “When I found him, he was half buried in the marsh mud, and the tide was coming back in. He wasn’t saying anything, just had this blank look on his face. I remembered this issue of Boys’ Life where they talked about rescuing someone from the ice. I had to crawl like a turtle out across that mud to get him.”

By the mid-1980s, magnetometers capable of peering deep below saltwater, mud, and sand enabled previously impossible searches. He often set out with an author/historian named Jack W. Melton, Jr., who has penned an authoritative guide to Civil War artillery, and he made the acquaintance of Harry Ridgeway, a relic hunter from Virginia. Discoveries of massive and valuable shells all along the Southern coast followed. Recovering a 200- to 400-pounder was particularly perilous. “Charleston is the hotbed,” says Ridgeway, a prolific shell hunter and memorabilia dealer known as the Civil War Relicman. “The exchanges of bombardment resulted in a lot of misses, and the shells would go sailing past their targets into the swamps. But it’s very difficult to find them, and very dangerous. All you see is that marsh grass, six, seven, eight feet tall. You sink up to your butt immediately. You get stuck, the tide comes in, and you’re just gone.”

Other hazards of relic hunting are of the crawling, biting variety. The thousand or so forested islands that run from Charleston to Savannah teem with rattlesnakes, black widows, Lyme disease ticks, mosquitoes, and the occasional rogue alligator in a freshwater impoundment. “When you’re out on an island, and you hear a giant bullfrog sound,” says the Big Iron Man, “that’s a mama alligator lettin’ you know you’re near her young.”

At that, his wife hefts a Confederate cannonball recovered from just such an island. It’s been cut into cross section, its terrible interior payload plainly visible. Confederate troops used whatever they had on hand as shrapnel agents because they couldn’t afford lead balls. “That’s how you know it’s Confederate,” says the Big Iron Man. “Johnny Reb would use nuts, bolts, anything.”

He hands me an iron sphere the size of a billiard ball, part of a load of grapeshot. “Grape was like a big shotgun shell,” he says. “The troops were marching in and they’d fire grape into ’em. Thirty people would just disappear in a mist of red. It was horrible.”

If these weapons inflicted such misery, I ask, why preserve them? “People have been trying to kill each other through all of history,” his wife replies. “Well, this is how they did it from 1861 to 1865. It illustrates not only the advances in technology, but the differences in resources between the North and the South.”

Her husband props his feet up on a fifteen-inch Union cannonball. “The Yanks were throwing these at Battery Wagner on Morris Island,” he says. “That’s solid iron, four hundred and eighty-five pounds. Can you imagine what it took just to handle the cannon that fired this? It would damage a modern warship.”

“If you don’t understand history,” his wife adds, “how can you understand human beings? This isn’t just iron. It’s engineering and technology. It’s the bravery of the soldiers. It’s the sheer foolishness of it all.”

Historical value aside, the shells’ lethal potential sets them apart from other collectibles. Not far from my house in Charleston, a small graveyard holds the remains of fifteen-year-old George Nungezer, Jr. In 1947, Nungezer, ten-year-old William Beas-ley, and two older cadets from the Citadel military academy managed to extricate a 200-pound shell from a cannon at Fort Johnson, the onetime site of a Confederate battery. After an employee at the Fort Johnson quarantine station drilled out the shell for the boys without incident, they set about knocking out its remaining black powder with a hammer so they could fire a toy cannon with it. When a spark ignited the powder, the youngsters were blown out of the tool shed. George died the same day. William lost a leg and suffered grievous burns.

Photo: Ben Gately Williams

Ordinance Depot

The Big Iron Man in his workshop with a rare set of 485-pound Union cannonballs.

More recently, two incidents shook the relic-hunting community. In 2006, an experienced shell restorer named Lawrence Christopher lost an eye and a few fingers when a shell he was drilling in his Dalton, Georgia, garage exploded. The sheriff’s department confiscated his collection—perhaps $100,000 worth of mostly disarmed shells, harmless as dumbbells—and destroyed it. In 2008, an equally experienced but cavalier Virginia collector named Sam White was blown up in his driveway while working on a nine-inch Navy shell. This makes him, quite possibly, the very last casualty of the War Between the States.

“The recovery of these artifacts can be done safely,” says Jack Bell, “but it’s got to be done with great care.” Bell, a friend of the Big Iron Man’s who now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, is the author of Civil War Heavy Explosive Ordnance, a 500-plus-page tome that collectors and professional historians consider a bible. Although none of the relic hunters he deals with consider themselves outlaws, in a sense they are. Federal regulations leave them with little choice. To legally transport a live shell, you need a federal permit. To receive a live shell, you also need a permit, along with an inspected storage magazine (essentially a sturdy metal toolbox). Restorers generally get around this by not transporting shells themselves and by defusing live ones immediately, so that nothing live remains on their property.

Most shell hunters would prefer to have a clearly legal means of having a shell disarmed and then returned to them. But there isn’t one. The Marines are the only branch of the military authorized to render a shell inert. “If you brought us a solid iron shell to have us identify,” says Lauro Samaniego, an EOD officer at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, in South Carolina, “we’d probably hand it right back to you. But if we determined it was a live one with powder, we probably wouldn’t. We have very strict guidelines; if it poses a danger, we have to keep it.”

Photo: Ben Gately Williams

Historic photos in his collection show a fearsome arsenal.

Despite this black-powder gray area, the Big Iron Man reckons that nothing is likely to change anytime soon, and that’s a shame. “Before a shell leaves my property, it’s always disarmed,” he says. “I talked to a guy in Georgia not long ago who wanted a live one. He says, ‘Well, I figure if it’s been safe this long—’ and I interrupt him and say, ‘Wait, it’s not safe at all. What if you get in a wreck and your car catches fire? What if your place catches fire and an eleven-inch ball goes off?’ If a person is afraid to have a shell taken away from him, he might not have it disarmed at all. And that creates a way more dangerous situation.”

Which is why Simons Young, the Charleston architect, is so glad that he found the Big Iron Man. Today his 100-pound Parrott sits on a mantel, basically the centerpiece of his family’s carriage house. “People come in and say, ‘Where did that come from?’” Young tells me. “I say, ‘Right beneath your feet.’ They just can’t believe it. I know we probably should have called the bomb squad when we found it. But if we had, it wouldn’t be here now.”