Arts & Culture

Thirty Years of Steel Magnolias

The untold story of what would become one of the most beloved touchstones of Southern culture

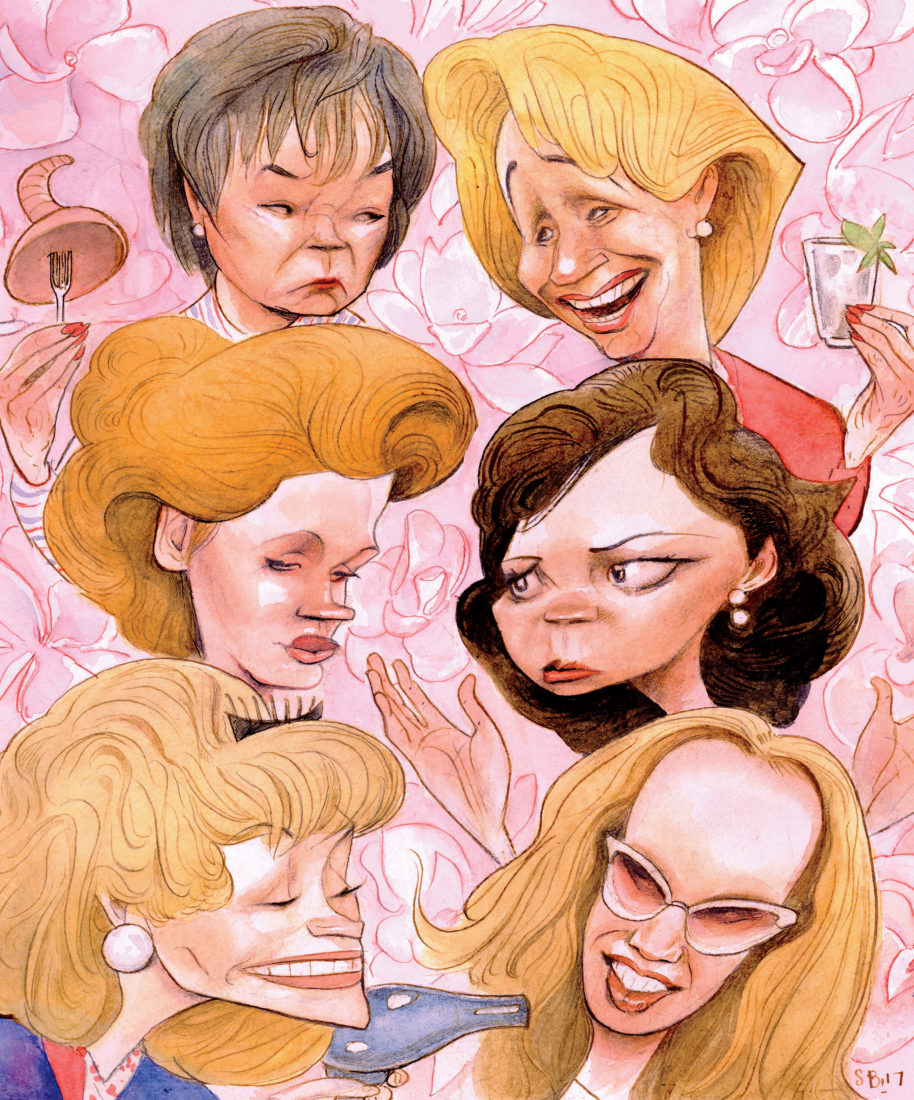

Illustration: Steve Brodner

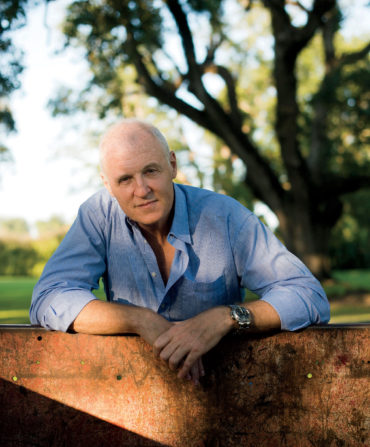

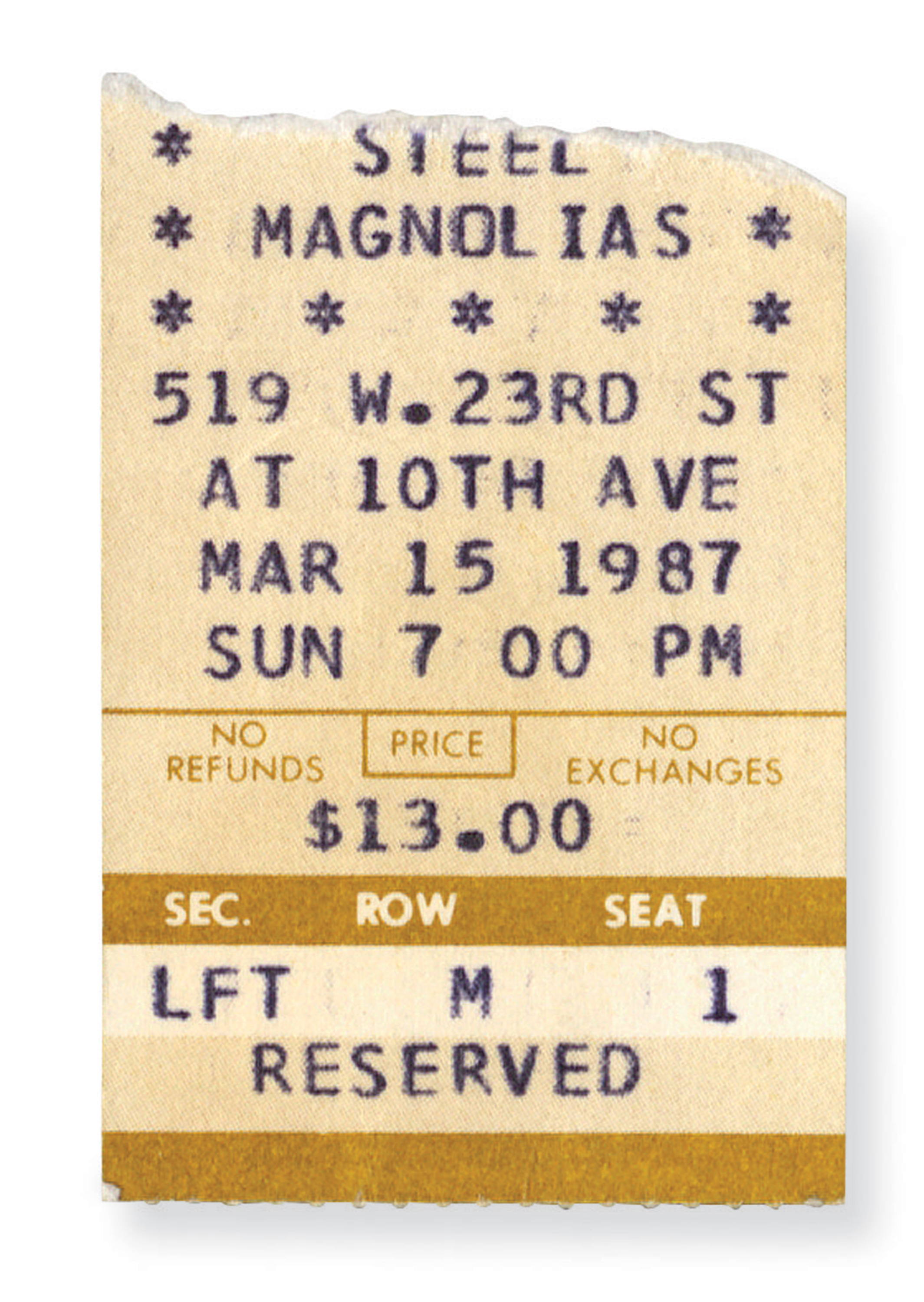

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of Steel Magnolias, a play Robert Harling wrote just months after his sister, Susan, died of complications from diabetes. Written as a tribute to the strength of his sister, his mother, and the coterie of women who supported them, the work broke records at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in Manhattan, where it ran almost three years. It has since been performed in dozens of countries, including Sweden, South Africa, India, South Korea, and Japan. Less than a year into the play’s run, the legendary producer Ray Stark bought the film rights, and in 1988 it was made into a movie starring Sally Field and Julia Roberts as the mother/daughter characters, M’Lynn and Shelby.

Steve Brodner

Harling, who grew up in Natchitoches, Louisiana, did not set out to be a playwright. While a student at Tulane University Law School in New Orleans, he sang with a big band and performed in summer community theater. When he graduated, he chose acting over lawyering—“He didn’t even pick up his diploma,” says his dad, Bob Harling—and moved to Manhattan with a promise of a month or two of support from his parents. He arrived in 1977 without a coat in the middle of a snowstorm. “I cried for an afternoon,” he says, “and then I got the list of auditions.” He had some success in regional theater and was cast in lots of commercials (his agent told him he had a great “food face,” meaning he was photogenic even while eating). Then, eight years after his arrival, his beloved younger sister, Susan, who had been a diabetic since she was twelve, got sick. Harling’s mother donated one of her kidneys, but in the end, the transplant couldn’t save her daughter.

ROBERT HARLING Susan was incredibly supportive after I came to New York. She was familiar with my frustration in terms of auditions, and she used to say, “You know what really makes me mad is the fact that I can’t do anything for you. I can make food for Johnny [Harling’s younger brother], I can whip Mama and Daddy into line, but I don’t know how to help you, and I wish I could.” Even when she was sick, she’d come home from the hospital and make a box of brownies and send them to me.

Everything they talk about in the play is true. Not every diabetic is the same, but because of her particular condition, the doctors were concerned that carrying a child would affect her. But she wanted a child, she went ahead and had a child, and then, sure enough, her metabolism started to fail—circulatory system, kidneys, the whole thing. It was much grimmer than I portrayed it in the play. Nobody could sit through the actual health dilemmas that my sister went through. It was so powerful to me because here was this incredibly strong woman—my mother—who had really fought Susan when she said she was going to try to have a baby. And now here was Susan having to turn back to her and say, “Mama, you need to help me now.” When she needed a kidney, we were all tested to see if we were matches, but my mom basically said the buck stops here, and that’s how it was.

The last time I talked to Susan was on her birthday, October 7 [1985]. She was on dialysis and they were going to put in some shunts to facilitate it, and that required some minor surgery. I actually had to get off the call because I was going to an audition. She said, “Good luck,” and they rolled her down to the operating room. She never woke up, and I told her story.

Harling says he went to a place of “rage and anger,” a state exacerbated by the fact that his sister’s widower remarried shortly after her death. Even more difficult was the fact that his nephew began calling his stepmother “Mama.” Harling was afraid Susan would be forgotten.

Photo: United ArchivesGmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

The Steel Magnolias ensemble on set.

ROBERT HARLING I had two dear friends, Kathy and Michael Weller. Michael is a wonderful playwright [Moonchildren, Spoils of War]. They saw what I was going through, and Michael suggested I write something. Such a saga of strength and tolerance had gone on, and I kept saying, “This kid won’t know anything about it.” I wasn’t a writer, so I fought that demon for a while and then one day I said, “Why not?” I’d planned to write a short story, and I was a couple of pages into it when I realized I wasn’t capturing the way these women talked. So I started writing in dialogue form. When I was a kid, the mystique of the beauty parlor was that guys were never allowed. You didn’t know what went on in there, and they all came back different somehow. I realized this hermetically sealed environment would be the best place to have these women express their true feelings. After my sister’s funeral, everybody came over to the house, and there was all this food. I was watching the men in the den, and they were a mess. My dad couldn’t talk about anything; none of them knew what to do. And I could see into the kitchen, and there were all these women and they were laughing and telling stories and dishing things out. They were saying things like, “You know this would be a lot better if she had just put a little white pepper in it.” And I thought, “This is very interesting. The women are getting it done and the guys cannot function.” And then one of the men walked into the kitchen, and I saw how the women’s body language completely changed. They weren’t leaning against the counter anymore; the dish towel that was slung over a shoulder was all of a sudden being folded and hung up on the rack. Later I thought, “This play needs to be somewhere there can be no men,” which was, of course, the beauty parlor, and I started putting the characters together.

Harling didn’t want to use real names, so he gave the character based on his mother the name of a close friend from Alabama, who was called M’Lynn. After a search through a family tree, Susan became Shelby, after one of his mother’s cousins. “It’s that Southern thing of using a family name as a first name,” Harling says. Clairee came from “a fabulous aunt” in South Carolina, and his sister’s best friend was named Ouiser. “She in no way resembled the character,” he says. “But there was just something about the name that fit.”

ROBERT HARLING All the characters were based on real people, Mama’s friends. I’ve never told a living soul who Ouiser is based on. After the play had some success and everybody from Natchitoches went up to New York to see it, I was really worried because Ouiser’s such a crotchety old curmudgeon. And lo and behold, every woman in town was saying, “He based Ouiser on me.”

Photo: Tristar Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Oylmpia Dukakis and Shirely MacLaine.

Harling says the name Annelle just came to him one day—“It’s so Southern to take two first names and just jam them together.” And then there was Truvy, the operator of the salon.

ROBERT HARLING I knew the actress Margo Martindale, who is now a huge star, and I wrote the role of Truvy for her. At the time, Margo was a working actress from Jacksonville, Texas, and she had this incredible voice. I wanted a name that fit her. I thought, since people come to the salon to tell the truth, there’s something about Truvy. It sounds like something her granddaddy might have called her as a kid. She loved it.

MARGO MARTINDALE Bobby and I were introduced by our commercial agent, and it was instant love. From the moment we met, he tailor-made the part for me. At the early stages of readings, I was attached, and when the play was finally produced, it came with me.

ROBERT HARLING So I put these ten characters in a beauty shop, and it only took me ten days to write it. When I finished the play, I took it to the receptionist at a literary agency, and she gave it to one of the agents. The feedback was “It’s not commercial because it’s a bunch of women and it takes place in a beauty parlor, but we’ll send it out.” Well, all these people wanted to do it. We did a reading of it at a small off-Broadway theater, the WPA, which had an amazing reputation—Little Shop of Horrors started there. And there was an equally amazing director, Pamela Berlin, who totally got it. She would tell me things like, “You’ve only allowed a minute and fifteen seconds to wash and set a woman’s hair. We have to move the dialogue around so we have time to do these things.”

MARGO MARTINDALE I tried to quit several times during rehearsals because the actresses would piss me off, saying, “Oh, you’ve got to roll my hair like this, don’t do that.” I said, “I am playing a hairdresser. I’m not a hairdresser. I’m leaving.” Thank God it didn’t stick.

ROBERT HARLING Margo’s hometown is just over the border from Natchitoches, so it’s kind of the same world. All I’d have to do was listen to her read the lines to realize when things were too verbose. Also, I had the voices of the women I grew up with. It takes your breath away how quick they are. It’s the kind of humor that would sear through treacle. The default was not to break down, the default was to change the conversation or lift it somehow.

MARGO MARTINDALE But we played it like a drama. We all thought it was a drama, and then the first night it was in front of an audience, we were shocked. It was riotously funny and played straight as an arrow. It was never like any of us thought we were doing jokes. We thought we were just talking like the people from that part of the country talk.

ROBERT HARLING It’s like the line “There is no such thing as natural beauty.” That was something somebody said who sold makeup in Natchitoches. That was a statement, not a joke. But when you put it in a theatrical situation, people respond to the honesty of it.

As the years have gone by, there are a lot of lines that get quoted back to me. There’s a moment where Ouiser has just had a tirade about how she hates kids, and people are parking on her lawn, and she’s really spewing anger, and M’Lynn says, “Well, Ouiser, if that’s really the way you feel, you should come down to the mental guidance center and talk to somebody. We’re there to help.” We were in previews, and the actress who played Ouiser, Mary Fogarty, God bless her, came to me and said, “I need to say something. I’m the meanest woman in town and you hurl the biggest insult so far to me, I’m going to say something.” I’d written no line there.

I said, “Okay, say, ‘Oh, I’m not crazy, I’ve just been in a very bad mood for forty years.’” She wrote it on her hand. We were literally going into performance. So Pam and I are standing in the back and M’Lynn says her line, and then Mary, kind of glancing at her hand, said, “I’m not crazy…” The house detonated. It stopped the show.

Harling did not tell his parents he had written the play until just before it opened at the WPA, but he’d sent versions back and forth to his brother, John, who was working in Philadelphia.

ROBERT HARLING As we were going into production, Michael and Kathy Weller asked me what my parents thought about the play, and I said I hadn’t told them. It was the only time I’d ever seen Kathy get riled at me. I said, “It’s got to be a painful thing for them. We’ll do the play, it’ll come and go, and they won’t know anything about it.” I was just chicken. Kathy said, “You weren’t there through all of that pain, you didn’t watch your child die. If there is one moment of joy to be gained out of this experience, you cannot deny them that. If you don’t tell them, I will.”

They came to New York to visit a week before we went into rehearsal, and I got up some courage. They were just flummoxed—I wasn’t a writer. When Mama asked me if she could read it, I said, “You don’t want to. It’s about you and Susan and the whole thing.” But she’s a Steel Magnolia—she was going to read it. I gave her the script, and I’d walk past and she’d be sobbing, and I felt terrible. Afterward, I said, “Mom, we’ll just kill it, I can’t put you through this.” And she said, “It’s wonderful because it’s true.” She just closed it and that was it, end of topic.

JOHN HARLING Daddy never read it, so he didn’t know what the hell was going on. When we sat down in the theater on opening night, I was the most nervous I’d ever been in my life. Mama and Susan locked horns. They were both good strong Southern women—that’s what makes the play so good. But you never know how people are going to react having that kind of personal information up there onstage. So we sit down, and early on Truvy says, “We’re gonna be busier than a one-armed paperhanger.” I looked over at my dad, and everybody’s laughing and he’s not laughing, but he’s beaming because that’s his expression. I could visibly see his chest rise up. From that point on, the cathartic experience of Steel Magnolias started in our family. What people don’t understand is that it’s honest even below what they see as a story. It’s honest all the way down. The play really did work miracles, and I don’t use that term lightly. It helped us grieve. We were basically grieving with the world.

BOB HARLING I felt happy, I felt sad, I just couldn’t believe what was happening. But I was mostly feeling good, proud. It was a memorial to my daughter.

Photo: Tristar Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Julia Roberts as Shelby and Sally Fields as M’Lynn after the wedding scene in the film.

MARGO MARTINDALE In the second act, when I talk on the phone to somebody, I would always put in, “See you then, Susan.” I think that finally got published in the play. It only ran for four weeks at the WPA, and we all wanted to figure out how to keep it going. I put money into it and Connie Shulman [the actress who played Annelle] did, and Bobby’s family did too. We moved the play to the Lucille Lortel.

ROBERT HARLING My father, my uncle, and our next-door neighbor all invested, and I was horrified—you almost always lose money in theater, but there was no stopping them. And then another neighbor told me, “You know it’s not about you, it’s about Susan.” And I realized that’s why they wanted to do it. They weren’t looking to make money, they wanted to support the continuation of the saga.

Shortly after the play moved, Hollywood came calling with offers for a movie, and every big-name actress turned up at the theater to see if there might be a screen role for her.

ROBERT HARLING Joan Rivers came, Lucille Ball came, Cher, Bette Davis, all of the Golden Girls. It became a nightly thing to see who was the huge star in the audience. Somebody had told Elizabeth Taylor that M’Lynn was the perfect role for her, and when word got out that she was coming, they had to shut the street. I was thinking at the time, “Elizabeth Taylor’s going to sit there and hear the line ‘When it comes to suffering, she’s right up there with Elizabeth Taylor.’” No one laughed harder than she did. It made the nightly news.

When the producer Ray Stark made an offer to buy the rights, Harling was thrilled. Stark had made the hit The Way We Were, and the plays he’d made into movies included Funny Girl and Chapter Two. Stark not only understood strong women, he also had a long working relationship with Herbert Ross, with whom he’d done eight films, including Funny Lady. Ross was hired as director.

ROBERT HARLING Part of the deal was that I would get the first crack at the screenplay. Herbert gave me the greatest, simplest advice: “Always remember who the important person is here,” meaning my sister. “Go back and ask what would amuse her, how she would edit, what would be too vulgar, where she would put her foot down.” So we got a draft of the script together, and Ray was happy.

SHIRLEY MACLAINE Herbert called and said, “I’m going to send you this script, and you can play any part you want, except for M’Lynn and the daughter.” So I read it and I said, “I want to play the really bitchy one.” I think I was rehearsing for my old age. I was seeing if I could get away with saying what I negatively felt and still be funny. And it’s kind of turned out that way, actually.

ROBERT HARLING Herbert had this way—he was from Brooklyn and started out as a chorus boy, but he became this acclaimed director and managed to talk like British gentry. So over dinner one night at Orso [the evergreen New York theater district restaurant], he said, “Rawbuht, how would you feel about Sally Field playing your muthuh?” I couldn’t speak. Then he said, “I was thinking that I’d love to see Dolly do Truvy.” And I almost choked on my pizza bread.

MARGO MARTINDALE I think they actually did see me for the role of Truvy, but that was just a courtesy, and I was not upset that Dolly got the role. Truvy’s all about heart, and Dolly Parton has a big heart.

ROBERT HARLING Just after my dinner with Herbert, Olympia Dukakis won the Oscar for Moonstruck. Ray called and said, “Olympia’s doing Clairee.” I knew Olympia from her work in New York theater, so I knew she could do anything, but I was worried that she wasn’t Southern. Shirley is from Virginia, and Sally had done Places in the Heart and Norma Rae, and then of course there’s Dolly. But when Olympia came down, all the women in town thought she had the most accurate accent.

Photo: Northwestern State University at Louisiana

Dolly Parton as Truvy.

1 of 5

Photo: Cammie G Henry Research Center

Daryl Hannah as Annelle.

2 of 5

Photo: Tristar Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Sally Fields as M’Lynn.

3 of 5

Photo: Cammie G Henry Research Center

Shirley MacLaine as Ouiser.

4 of 5

Photo: Tristar Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Dolly Parton and Daryl Hannah.

5 of 5

Next, Herbert said, “I really like Daryl Hannah for…” I thought he was going to the Shelby place, but before he got there, he said Annelle. I couldn’t imagine it. She was one of the great goddesses of cinema [Hannah had already starred in Splash and Roxanne]. Herbert said, “It’s a wonderful Hollywood move. She will jump at the chance to wear a bad wig and glasses.”

All that was left was Shelby. We’d decided on Meg Ryan, who had just had some success with Top Gun. The day we offered it to her, she came back and said, “I just got offered this movie with Billy Crystal, When Harry Met Sally, and that’s my chance to be a leading lady. In Steel Magnolias I’d be part of an ensemble.” We went back to the list: Laura Dern, Winona Ryder, all the hot young stars. Ray said, “You know what, we’ve got a lot of Oscar winners and stars. Let’s open it up.” The casting director said, “There’s this girl. She hasn’t been able to audition because she’s been off making some movie about a pizza.” [Roberts had just finished filming Mystic Pizza.] Julia came in, and it was like somebody bumped up the lights. She smiled that smile. She was the essence of the great Southern gal: spicy, witty, smart, with a layer of compassion underneath. [Roberts grew up in Smyrna, Georgia.] Lee Radziwill, who had just started dating Herbert, said, “She’s it. She’s Shelby.” I thought, “Okay, I can breathe now, my sister’s in good hands.”

Photo: Cammie G Henry Research Center

Julia Roberts as Shelby.

SHIRLEY MACLAINE The moment Julia walked into the reading, I thought, “That woman is going to be a star.” I called my agent and said, “I don’t know if she has an agent, but you should handle her.”

During the casting, Stark also made the decision that the movie would be filmed on location, an extraordinary move at the time.

ROBERT HARLING Ray said, “Why don’t we shoot it where it happened?” That was unheard-of—normally you’d find your locations in the Valley and in L.A., but Ray insisted. It helped that Natchitoches is gorgeous. Anywhere you point the camera you’re going to frame a good shot. It’s the oldest town in the Louisiana Purchase. It has a sense of history you could never capture in Pasadena. But first a lot of stuff had to happen. They had to start bringing in all these people and all this equipment to this little tiny place. Finally, the date was set, and we started shooting at the end of June 1988. The circus had come to town.

The filming lasted through Labor Day, and all the stars lived in houses in Natchitoches.

TOM WHITEHEAD [Natchitoches resident and then member of the Louisiana Film Commission] There was a buzz in the community the whole time the shoot was here. There’s a restaurant called Mariner’s out on Sibley Lake, and every night Dolly, her assistant, the guy who did her hair, and her bodyguard went to dinner there. The restaurant was sold out for the duration. People filled it up to see Dolly Parton eating in the back corner.

Photo: Cammie G Henry Research Center

Robert Harling and his mother on set.

ROBERT HARLING Julia was so eager to have the stamp of approval from Mama and Daddy to play their daughter. She’d come over, and Daddy would cook hamburgers and they’d talk, and she’d write poetry and she’d read us the poetry, and Dolly would come over and sit on the sofa and play her guitar. It was just beyond surreal. Dolly wrote a song called “Eagle When She Flies.” It was written for the movie, and Herbert was going to play it over the credits, but he changed his mind. There’s a line about the “sweet magnolia” that originally had been “steel magnolia,” and she played it for my parents as she was writing it.

SHIRLEY MACLAINE It was really hot. There was Dolly with a waist cincher no more than sixteen inches around and heels about two feet high and a wig that must have weighed twenty-three pounds. And she’s the only one who didn’t sweat. She never complained about anything. Never. The rest of us were always complaining.

ROBERT HARLING We were shooting part of the Christmas scene, and this was in the dead of August, and we were sitting out on the porch of Truvy’s beauty shop. We were waiting, and there was a lot of stop and start. The women were dressed for Christmas, and Dolly was sitting on the swing. She had on that white cashmere sweater with the marabou around the neck, and she was just swinging, cool as a cucumber. Julia said, “Dolly, we’re dying and you never say a word. Why don’t you let loose?” Dolly very serenely smiled and said, “When I was young and had nothing, I wanted to be rich and famous, and now I am. So I’m not going to complain about anything.”

TOM WHITEHEAD They all lived life locally. Tom Skerritt [who played Shelby’s father] rode his bicycle to a restaurant downtown where he ate his lunch most days.

ROBERT HARLING Tom Skerritt was two houses down from where my father lived, so I had my fake father, Drum, out picking up sticks from a storm in the yard with his khakis rolled up, and there was my real father in his yard doing the same thing. Olympia lived down the street. Michael Dukakis [Olympia’s cousin] was running for president that summer, so Olympia was all involved and spoke at the Democratic convention. It’s a very Republican area of the country, but there were some people who put Dukakis signs in their yard just to be neighborly.

SHIRLEY MACLAINE I loved studying the townspeople and walking through their lives a little. I’d go to the ice cream store and the magazine place and the video store. I just wanted to see how people acted, how they belonged to themselves.

ROBERT HARLING The L.A. people required things that you didn’t find at the local Piggly Wiggly. I remember the manager of the store saying to a local reporter, “Yep, if it hadn’t been for Herbert Ross, nobody around here would know the difference between osetra and beluga.”

SHIRLEY MACLAINE We immediately saw that Herbert was cruel to both Dolly and Julia. I don’t know why, except he was basically a choreographer, and choreographers tend to be cruel in the name of art. Julia’s feelings were hurt, and we lived next door to each other, and she was over every night. We talked about life, and I tried to help her because I was a dancer and understood the choreographer mentality. Then one day I basically told him to go f**k himself and everybody heard it and things got better.

Photo: Tristar Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Dolly Parton and Daryl Hannah.

MacLaine hastens to add that Ross was a “good director” and that in some ways the conflict turned out to be a good thing.

SHIRLEY MACLAINE We became protective. We became one. We really did make fast friends, all of us, and have been ever since. I don’t know what it is about the subject matter in the movie, but going through that makes you friends for life.

ROBERT HARLING I’m still working out the ramifications of this whole insane journey that only art can let you move through. Because what is art other than taking the pieces around you and re-forming them into some vision that satisfies you and enriches others? My mom and dad had their own kind of come-to-Jesus moments with all this stuff. But you know, my sister died and I wrote about it and people look at it and think it’s all limos and glamour and sitting next to Princess Di at the royal premiere. My sister had to die for all that to happen. So almost daily I think about what my life would be if she had lived. It can take you to an uncompromisingly dark place sometimes. Then I just have to go back to the honesty of the first impulse, that I just wanted somebody to remember her.