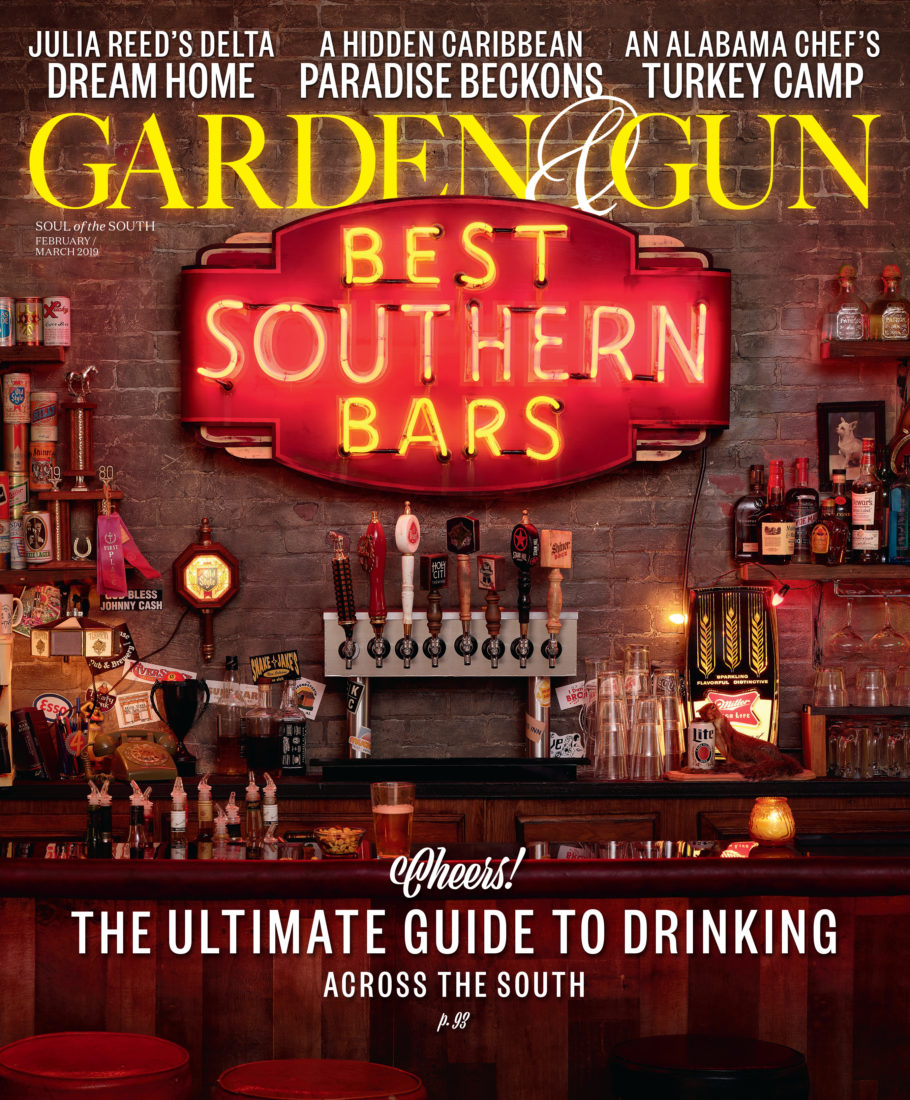

Sporting

A Weekend at Turkey Camp

Each spring, Birmingham chef Chris Hastings invites a handful of friends and their children to his camp in Alabama for a week of hunting, camaraderie, good food… and a few life lessons

Photo: William Hereford

From left: An Eastern wild turkey from the Alabama woods; Chris Hastings (left) and the author head out in search of an afternoon bird.

It feels right. There’s no other way to describe it. It is the first morning of a three-day hunt, in the spring woods of central Alabama, and already five turkeys have gobbled and the sun hasn’t yet cracked the ridgeline. Sometimes, in the turkey woods, you are certain that they didn’t hear you coming in the dark and that your quiet little yelps from the slate call hit all the right notes. You know that you are hidden well and you haven’t moved a muscle, and you feel in your soul that it’s going to happen at any second: In the next moment, or the one after that, surely, the snowball-white head of a gobbler will appear behind the ridge to the left. Or in the gulley to the right. Or from the dark pinewoods above. And despite this certainty, you know as well that it is the turkey that holds the cards.

And suddenly, the turkeys go quiet. Titmice and blue jays and redstarts are calling, but the turkeys give us the silent treatment. I feel Chris Hastings shift, ever so slightly, his left shoulder against my right arm, and in that subtle movement I realize that it’s all gone wrong. “I think we were almost too sneaky,” he whispers, and I feel the confidence and pluck leaving my body. “I think we’re right in their bedroom.”

Photo: William Hereford

The author listens intently to the sounds of the spring turkey woods.

“Too close,” I reply. “They don’t like that.” At that moment, we both know that it’s not going to happen.

Which, under other circumstances, might be concerning. But the day is young, and I have two more to hunt. And I’d always rather work hard for a bird. For Hastings, particularly, despite the incredible effort he puts into this hunt, a long gathering with longtime friends, despite the days of scouting and cooking and prepping and obsessing, shooting a turkey has never been the point. It’s the objective, make no mistake, and Hastings is as passionate a turkey hunter as you will find. But for these few days, under his tutelage, fathers and sons will hunt side by side, and share meals and chores and conversation.

Hastings choreographs some of these experiences with no less strategy than he plots a morning turkey hunt. What does it mean in the twenty-first century, he asks, to be a gentleman? What of value from the Old South do we bring into the New South, and what do we abandon? What does a man owe to another man? A father to a child? Seeds planted, for harvests that might not occur for years. The killing of a wild turkey is a meager metric by which to gauge success at Chris Hastings’s turkey camp.

This week in the spring Alabama woods offers for Hastings a sacrament. For nearly a decade, he has hosted what he calls, simply, “turkey camp.” It is an uncharacteristically prosaic moniker. Hastings is a renowned Birmingham presence, executive chef and co-owner, with his wife, Idie, of Hot and Hot Fish Club and the relatively new OvenBird, an eatery opened in late 2015 that relies on open-fire cooking traditions. He’s been nominated three times for the James Beard Best Chef: South award, winning the honor in 2012.

Photo: William Hereford

A turkey hangs before becoming a meal for the camp.

Hot and Hot Fish Club, in Birmingham’s thumping Five Points South neighborhood, has been a city staple for more than twenty years. It’s named for a nineteenth-century Friday evening gentleman’s gathering in the Pawleys Island, South Carolina, Lowcountry. Hastings’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, Hugh Fraser, was a charter member of that original Hot and Hot Fish Club, which involved a little drinking, a lot of conversation, and whatever fish were caught that day. The Hastingses’ current iteration is a painstakingly crafted expression of what Chris’s ancestor had by happenstance—an experience, he explains, “that is of a place, and not of any other place.”

Photo: William Hereford

A bird’s-eye view of the Tallapoosa River near Lake Martin.

He exports that line of thought to his Alabama turkey camp. For these few days, his cabin overlooking a wide bay of Lake Martin is a carefully orchestrated vision: Massive sprays of fresh-cut dogwood and wild azalea—which he hunted in the woods with no less zeal than he pursues turkeys with—spread across soaring eighteen-foot-tall heart-pine walls. Bars practically sag with bourbon; coolers are filled with beer. He has laid in stocks of oysters and crawfish, rutabagas and turnips. And Hastings has scoured the woods for four straight days, searching for turkeys, monitoring their movements, careful not to push them too hard before his hunting guests arrive.

The event began with a few spring-woods conversations he had with a friend, John Vawter. The pair started hunting turkeys in the nineties, and although it was five seasons before they shot the first bird, the bonding between the young men helped spawn the idea of a purposefully constructed parent-child weekend that might model the kind of life approach they felt was all too rare in the modern world.

Photo: William Hereford

Dogwood boughs grace the bar at Hastings’ cabin.

“We had kids about the same age,” Hastings recalls of those early discussions, “and we made a pact to raise our children a certain way. As parents, we wanted to be present. We wanted to raise them to be proper, which is different from popular. And we realized that they would need strong mentors, who they could learn from, yes, but also who they could count on to be there for them for the rest of their days.”

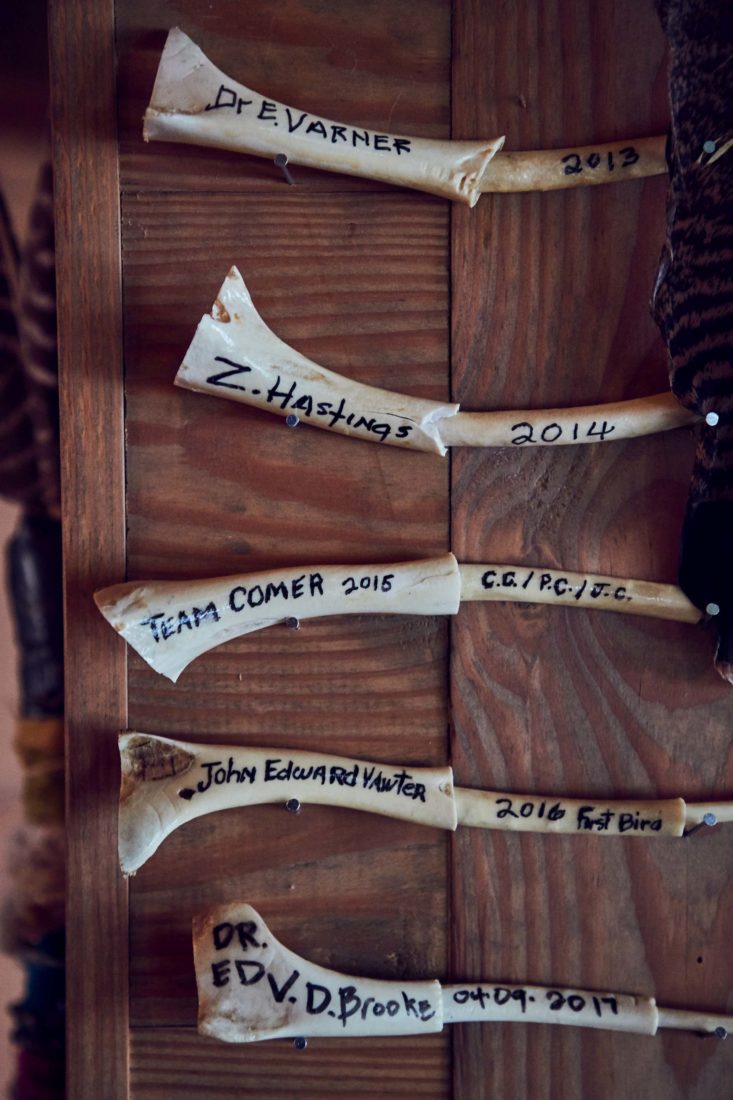

Starting in 2010, and every year since, Hastings has invited this small group of a half dozen fathers and sons to his cabin by the lake. They hunt wild turkeys, certainly, every day and hard at it. But there are communal meals at which everyone plays a part. Spirited conversation. Lessons, both obvious and nuanced, handed down.

Photo: William Hereford

Hastings cleans a turkey.

“It’s rare that older men and younger men sit together, shoulder to shoulder, for five hours,” Vawter says. “These young men get to see how other fathers parent their own children, and they learn that parenting doesn’t come out of some rule book. That we’re all doing the best we can, and our best is informed by the best of everyone at this camp. That’s a very rare and valuable set of relationships.”

“Chef,” as most of the other men call Hastings, takes his role seriously. In the kitchen one afternoon, the men gather around thirty pounds of boiled crawfish and a bushel of oysters. Two younger boys sidle up to the crawfish and dig in. Hastings admonishes them, lightly.

Photo: William Hereford

Oysters, crawfish, and, of course, turkey are often served at camp meals.

“What are y’all doing over here in these mudbugs?” he says, eyebrows arched over his glasses. “Help with the table. Y’all can come back then.” He nods toward the long dining table where the other boys are setting out silver, stemware, and a dozen candles. He looks toward the men. “We all understand what this is about. We are intentional about providing a great place for older men and younger boys and girls to bond, to learn the traditions of being in a culture of Southern family, and how that can shape your life.”

He doesn’t linger on the lesson. No outright pedantry here.

“So, let’s talk about the hunt in the morning,” he says. “Who’s going where?”

It is Saturday morning, day three of the hunt, and everyone is feeling the pressure. Heavy rains have hammered the woods, making it difficult to call wild turkeys. But this morning a clear forecast has every father and son out of bed and on the move. Hastings and I have posted up along a ridge flush with dogwoods, their flowers visible long before dawn.

Photo: William Hereford

Turkey camp participants from the Hastings, Varner, Brooke, Vawter, and Comer familys.

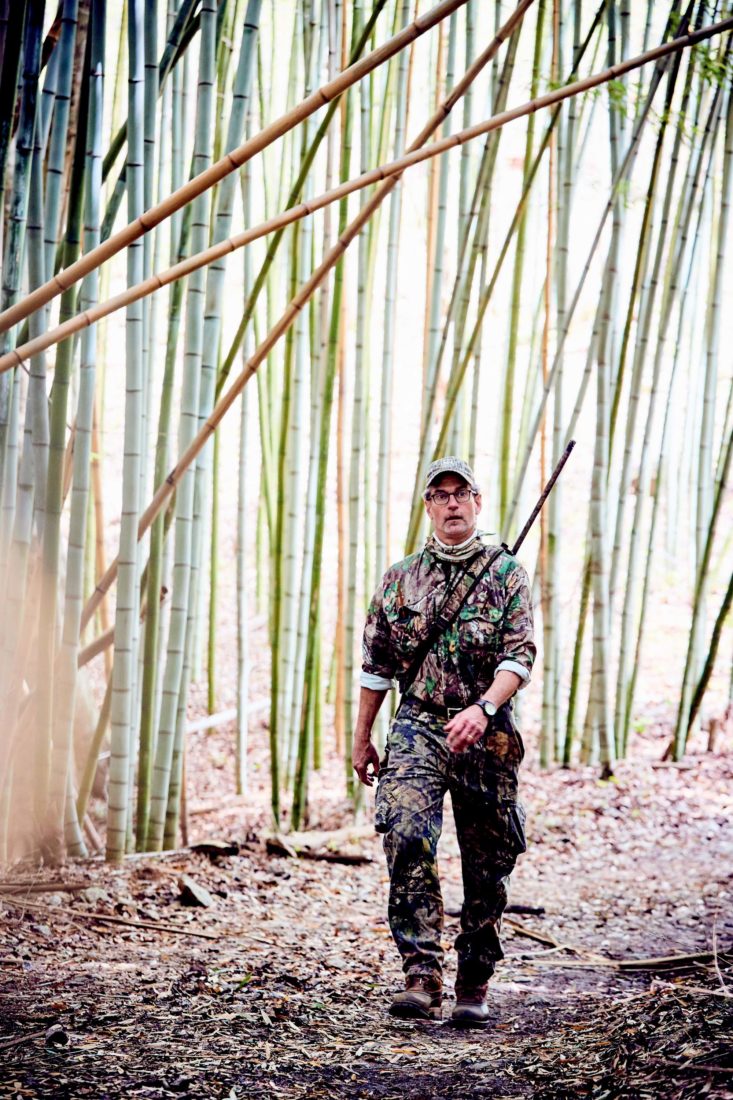

In the woods, Hastings doesn’t wear a turkey vest. He’s a bit old-school in his approach to turkey hunting. He carries his turkey calls—slate call, glass call, two strikers—in the breast pockets of his shirt, the strikers protruding from each buttonhole as if he’s packing a pair of chicken drumsticks for lunch. He uses decoys sparingly, and he can’t abide decoys with moving and mechanized parts. “They are,” he says, pausing for thought, “disrespectful.” He sits directly on the ground. There’s no kicking and scraping the leaves away from the base of the tree so he can quietly shift his weight or stretch a leg. He doesn’t make noise, because he hardly twitches a muscle, hour after hour.

With its array of calling techniques and decoys, turkey hunting is an amalgam of the purely natural and the wholly contrived, the authentic and the fabricated. When—and if—a gobbler appears, tail fanned and drumming, it’s a moment born of both intentionality and fortune.

And that explains the peculiar affinity between turkey hunting and parenting, for all parents do this: We work to create these fabricated moments, in the hope that something enduring takes place between ourselves and our children.

“You have your ass handed to you in the turkey woods,” Hastings says, by way of an example. “It happens day after day after day to a young turkey hunter, and they never realize what they are learning. That this is life, and

life requires patience and work and dedication and respect, and a little bit of cunning and luck doesn’t hurt, either. That there is a difference between walking out of the turkey woods empty-handed and walking out of the turkey woods defeated.”

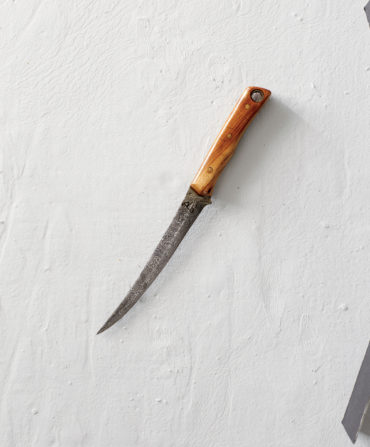

Photo: William Hereford

After a successful hunt, Hastings makes wingbone calls to commemorate the outing.

Later that day, back at the cabin, men and boys are scattered about, preparing dinner. Inside, where boughs frame the pewter prism of the lake, a soundtrack plays of knives on cutting boards and the murmur of conversation. Hastings is out by the lake, barefoot beside the firepit, breaking down a turkey he shot earlier in the week into its culinary components: breast, wing, thigh. Crawfish water is halfway to boil, and there are oysters piled up and waiting for the last of the hunters. Ed Varner and Dixon Brooke come dragging back to camp after thirteen hours on the hunt, fueled by nothing more than coffee and the siren sound of gobblers drawing them deeper and deeper into the woods. They chatter about busted hens and toms gobbling in the late afternoon and wild turkeys acting positively wild.

“In other words,” Hastings says, laughing, “you got nothing for us.”

They laugh and nod.

It is a powerful tableau, generations scattered from the lakeshore to the cabin kitchen, a commingling that on its surface seems coincidental and wholly unconstructed. But I know better, and it brings to mind an earlier scene, from a few days before, that now I understand as entirely Hastings-esque.

Photo: William Hereford

Hastings on a mission to find a bird.

It was the Thursday afternoon before the guests would arrive, and Hastings and I drove his SUV deep into the red-clay woods, down trails so narrow the brambles snagged my coat sleeves through the open window. At one point, Hastings slammed on the brakes, cocked his head as if considering some errant thought, then jacked the vehicle in reverse and bumped backward down the two-track. He stopped the Ford Expedition, vaulted out the door, and climbed out on the hood. Dogwood branches lurched violently overhead. Bark chips and twigs bounced off the windshield. Hastings had spotted a long dogwood bough, arcing through the woods, and it was just the thing he needed.

“Flowers are like the moon,” he called from above the hood, only his boots and jeans showing through the windshield. “I want them waxing, not waning.” He lopped off a long branch, ten or twelve feet of swooping foliage and blossoms. There was a space in the dining room, framing the lake, that Hastings needed to fill. “I get a little particular,” he said. “It’s got to be configured properly.”

He was as animated over the dogwood branch as I would see him all weekend. He held it aloft as he slid off the hood, then threaded the bough through the back hatch, as carefully and gently as a man lays a sleeping child into a crib.

It was the last thing on his list, he said. He climbed into the driver’s seat and sat quietly for a moment. More thinking. He is always thinking. “I want my friends to step into the cabin like they are stepping into the woods, surrounded by wild azaleas and dogwoods, the smell, the flowers, all of it, all around them,” he said. “I want them to feel the moment, because this is the time we are given, and it doesn’t last long.” He cranked the motor. No matter what might happen over the next few days, with the weather or the birds or the hunting, Hastings was ready. He might not be able to conjure a gobbler out of an Alabama morning, but this he could do: At Lake Martin, in his cabin in the turkey woods, he would set the table.

Photo: William Hereford

Time at the table is just as important as time in the woods.

T. Edward Nickens is a contributing editor for Garden & Gun and cohost of The Wild South podcast. He’s also an editor at large for Field & Stream and a contributing editor for Ducks Unlimited. He splits time between Raleigh and Morehead City, North Carolina, with one wife, two dogs, a part-time cat, eleven fly rods, three canoes, two powerboats, and an indeterminate number of duck and goose decoys. Follow @enickens on Instagram.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.