Arts & Culture

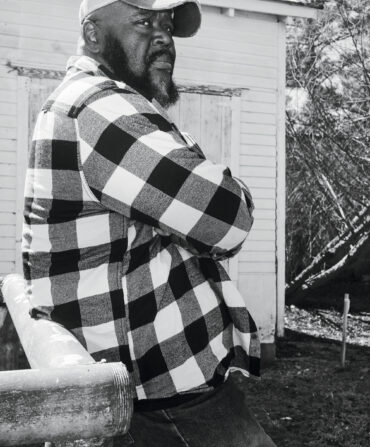

Two for the Road: A Son’s Eulogy for his Father

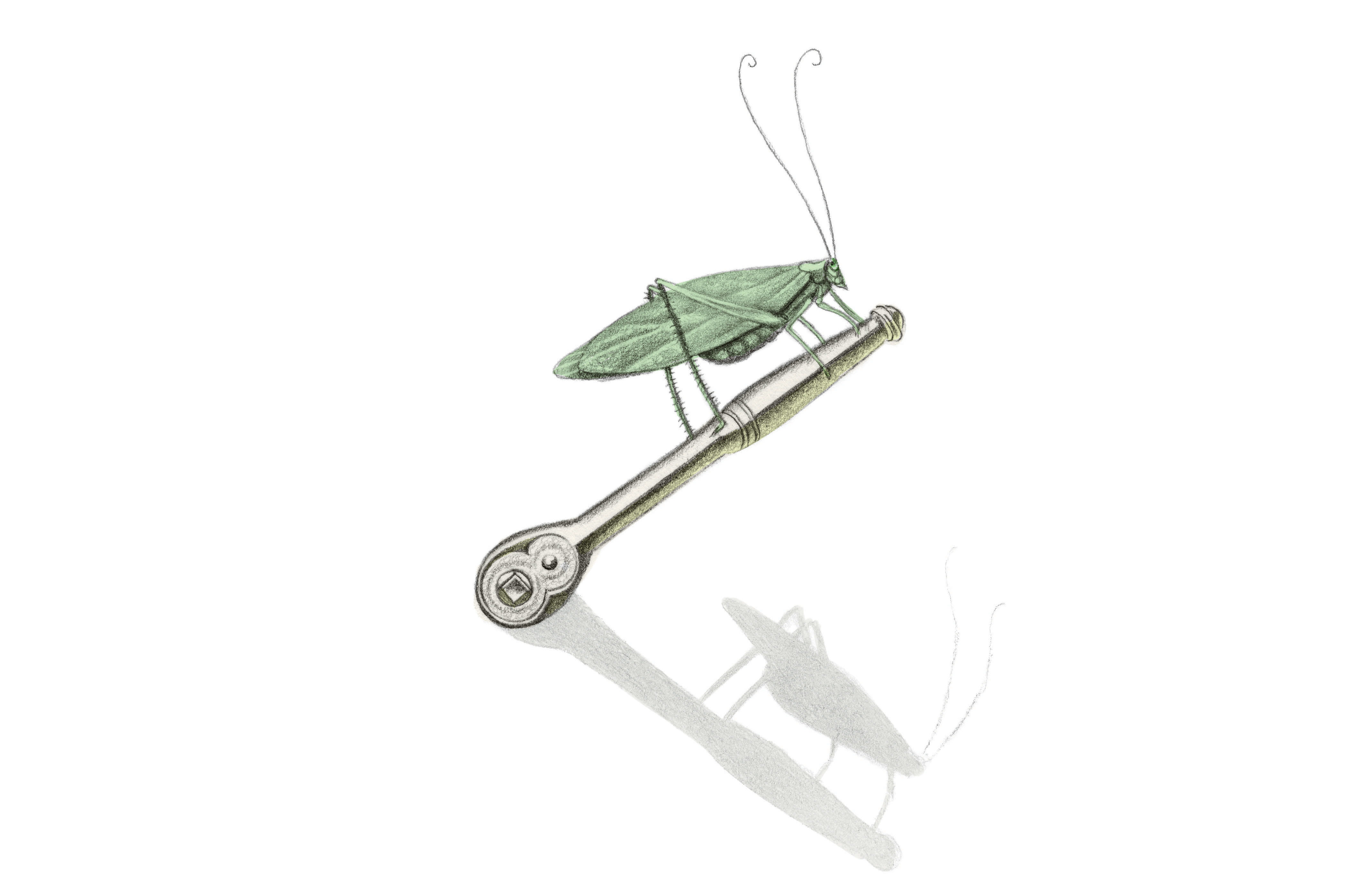

Illustration: Armado Veve

He was born on the Fourth of July, 1947.

The eldest of six siblings, he spent much of his childhood in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he had a paper route on his bicycle and then his scooter—perhaps discovering then his love of two wheels.

I picture him on his two-stroke Vespa, sky blue with bloody clouds of rust, crackling and smoking across the bridges of Pinellas County. It is dusk. The evening papers, hot from the press, are rolled like warm loaves in his leather satchel. His taillight is a red ruby in the falling darkness.

The year is 1961; he is fourteen years old. His hair is dark, wind-curled across his forehead. His eyes are squinty, like mine. He is looking across the waterways and canals that crawl inland from Tampa Bay. He is watching the waters glow beneath him, dusk-born, like rivers of flame.

He is Rick Brown, my father.

Fifty-six years later, in the fall of 2017, I left my home in Wilmington, North Carolina, on my 1989 Harley-Davidson Sportster, “Blitzen”—a bike my dad and I had built together—bound for New Orleans. My route would take me down the old coastal highway, US 17, stopping overnight at my parents’ house south of Savannah, where I grew up, before heading west across the Gulf Coast. I was planning to spend Halloween in New Orleans, with a side trip to the Louisiana Book Festival in Baton Rouge, where I was due to discuss my latest novel.

My longest solo ride yet.

My father and I had named the bike Blitzen because of the enduro-style handlebars we mounted, high and wide like chrome antlers, and the fact that we built the bike over the Christmas of 2016, stripping down the stock machine and turning it into an oversize “scrambler”—a street bike modified for light off-road use, complete with taller shocks, knobby tires, and high-mount exhaust.

I’d had some adventures on Blitzen already. In the summer of 2017, I rode the bike one thousand miles up and down the Southeastern coast, exploring abandoned hotels and burned-out cars and beached boats with trees growing out of their hulls. I made friends with an armadillo living under my cabin on Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, and watched a trio of old men with chain wallets play gospel music in a North Carolina Wendy’s. That trip, Blitzen broke down just inside the county line on my return to Wilmington, and I managed to coax the sputtering machine across the Cape Fear River before it died completely. I pushed the bike the last mile home, watching our reflection pass through the windows of closed barbershops and furniture stores. All in all, an appropriate ending to the ride.

This time, however, I wasn’t even out of town before the bike was giving me trouble, a slight misfire. I called my old man. We usually spoke a few times a week. I’d been riding on the back of his Harley since I was in grade school. When I was in my early teens, we’d hunted the back roads of South Georgia for places to ride our dirt bikes. Now, with me in my thirties, we were becoming closer friends than we’d ever been. We’d worked side by side on Blitzen with hardly a tiff—no small feat when wrenching on a thirty-year-old motorcycle—and he was the “senior correspondent” of an online custom-motorcycle community I’d founded, BikeBound.com. What’s more, we’d begun to share a love of riding like never before. I still remember the knowing light in his eyes when I described the feeling of my first long solo ride, as if we now shared some secret discovery on the roads.

Armando Veve

Though he shied from speaking of it, his relationship with his own father had been fraught with difficulty and pain. How easy it would have been for him to follow that same pattern with his own children. Instead, he went against the grain.

I remember the first time he let me ride his prized 90th Anniversary Harley-Davidson Wide Glide. I was sixteen and we were on country roads south of the Florida line. When we stopped for gas, I pulled up next to him, overly excited, and my foot slipped in a patch of gravel. Almost in slow motion, I dropped the bike—six hundred pounds of Milwaukee iron, heeling over like a killed horse beneath me, my father reaching out to catch the handlebars an instant too late. I could see the pain and frustration in his face. But instead of lashing out, castigating his son for being careless or weak, the man gritted his teeth and brought his emotions to heel, even as he thumbed the new dents and scratches in his once-perfect machine. “Happens to the best of us,” he told me. True—everyone who rides a motorcycle will drop one sooner or later. Still, how easy to forget in the heat of the moment. Rick Brown didn’t. I believe that’s one of the great lessons I learned from him: that character often requires us to place what is right over what is easy.

Back in Wilmington, after a few minutes on the phone, we decided that Blitzen’s misfire was only a fleck of rust or tiny debris that made it through the fuel filter—the V-twin engine was throbbing low and steady now, like a mechanical heart.

I hit the road.

On rides like these, I always avoid the interstates—just as he taught me. There’s so much more to see on the back roads and byways. The roadside produce stands and junk shops, the Pentecostal churches and mom-and-pop restaurants and gas stations that serve coffee in tiny Styrofoam cups—the best coffee in the world when you’re just off your motorcycle, rain-soaked and shivering. And, for me, there’s nothing as therapeutic as a long ride on the back roads. It feels like the wind, gradually, blows away the nests of doubt and anxiety that gather inside us. I think, on motorcycles, we are uniquely vulnerable. We are, perhaps, closer to death, and that puts the lesser worries of everyday life back in their place.

I stopped at one of my favorite spots, a crusty old fishing pier just outside Georgetown, South Carolina, where I took a nap with my backpack pillowed under my head. At dusk, I crossed the enormous, cable-stayed bridge into Charleston, standing on the bike’s pegs to look across the gold-flickering city and down at the passing freighters, their multicolored shipping containers as small as LEGOs from this height.

After spending the night in Charleston, I took off early the next morning, riding south over the green-brown marshes and blackwater rivers of the ACE (Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto) Basin and the Carolina Lowcountry, bound for Georgia. My old man met me in downtown Savannah. We ate lunch together and went to a bookstore and sat at one of the hotel bars high over the water, watching the river traffic chug past. It was an unexpectedly special day.

A gift.

The next night, we sat side by side at the kitchen counter while we planned the next legs of my trip. I made note cards as he traced his fingers across the highways of worn atlases he’d used time and again. I was taking many of the same roads he’d ridden in times past, following his path across the Gulf Coast. So much of his past had taken on the weight of legend to me. There was his time in New Orleans, at Loyola, when he was known to shoot a marvelous game of pool, brushing shoulders with the likes of Willie Mosconi and William “Billy” Wells. There were the summers when he drove a Carling beer truck to make enough money to put himself through law school at the University of Georgia, and the summer he spent in the army at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, shaking tarantulas from his boots. There was his nine-thousand-mile solo motorcycle trip around the country, which he took when he was sixty-seven years old.

There are sons who want to be like their fathers, and sons who don’t. I’ve never doubted which I am.

When I slung my leg over Blitzen the next morning, our note cards were safe in my front pocket, wrapped in a plastic sandwich bag to protect them from the elements. It was October 16, 2017—two days before my thirty-fifth birthday. In a photo taken that morning, I’m wearing my secondhand

black leather jacket and my red backpack, and my dad’s old weatherproof duffel is tied over the back of my saddle.

Illustration: Armando Veve

The weather was foggy that morning. I rode over the bridges and causeways of the Georgia coast, where the water looked pale beneath the mist, almost white, winding through the darkened cordgrass of the fall-time marsh. I rode down Highway 17 through Camden County, Georgia, and then through a string of small towns, skirting the Okefenokee Swamp and the Osceola National Forest, making my way west toward the Florida Panhandle. I still have the note cards that tell me the towns—Folkston, Macclenny, Sanderson, Lake City, Branford—along with the trip checklist my father gave me, listing such necessities as “Tire patch kit/pump” and “Duct/electrical tape” and “Cigars/lighter/cutter.”

Around lunchtime, I stopped in Mayo, Florida, where I took photos of the Udder Delight ice cream shop and the city’s big white water tower, which states MAYO in bold black letters. I texted with my old man. He’d ridden to a diner called Steffens near the Georgia-Florida border for lunch and sent me a photo of a die-cast 1940 Ford coupe sitting on a shelf there—a model like the bootlegging car from my novel Gods of Howl Mountain, which we’d “researched” together at vintage car shows and moonshine festivals. He told me he’d checked the weather and the heavier rain was staying north of my route. He said Wakulla County, Florida—my night’s destination—was partly cloudy and eighty-eight degrees.

I didn’t reply. I was already back on the road.

When I got the call from my mom, I was at the lodge in Wakulla Springs, south of Tallahassee. I’d just arrived. I knew from the sound of her voice that something had happened, though details were scarce. There had been an accident. A concrete truck had pulled out in front of my dad’s motorcycle on his way home from lunch, on Highway 17 just north of the Florida line—the same highway I’d ridden that morning.

I was at the local airport, about to rent a car for the drive home, when Mom called to tell me he was gone. Minutes later, I found myself standing in the parking lot, staring up at the sky. It was sunset and the sky was almost the color of fire, and I thought how many times Dad had ridden down to Cedar Key or Hudson to watch this same sky turn to flame. At the rental desk, the woman’s name was Gracie. She gave me the number of a nearby Harley dealer in case I needed somewhere to store my bike—she said to tell them “Sunshine” had sent me.

Her biker name.

I spent the night at the lodge in Wakulla and started out early the next morning in the rental car, leaving Blitzen under a cover in the parking lot. My sister took the red-eye from San Francisco, and I picked her up at the airport on my way home. When we got there, Mom had an envelope waiting for us. Dad’s secretary of many years had delivered it that morning, a big manila envelope labeled with a single word: “IF.” Inside were letters addressed to each of us. Here is a little of mine:

Taylor,

If you are reading this, something has happened to me. I assume it was sudden and I didn’t have the chance to say goodbye. For that I am truly sorry…I am sorry that I won’t see even more of your novels published…or BikeBound continue to grow. I regret that I won’t see you find that right partner to share your life or be able to spend time with you talking or riding motorcycles. And we didn’t make it to the Isle of Man.

I know this is a difficult time but remember the good times we share—Sun & Fun, Sturgis, dirt bikes, Moonshiners’ Festival, Blitzen, Austin, and on and on. I have truly enjoyed all the time we spent together throughout your life (other than a couple of times playing golf 🙂 )…

What I want to stress in this letter is how much I love you and how proud that I am and always will be…

I don’t need to tell you that it takes a special kind of man to write letters like that.

What followed was a blur. A house full of grievers, meetings with the funeral home, the obituary, the service itself and giving the eulogy and shaking hands with countless people from my childhood. My mother and my sister and I came together—we were a damn good team. But I’d lived the last half a decade alone, and when it was over, I needed time to myself. I needed wind and movement and the roar in which I could hear nothing but my own thoughts.

I needed to finish the ride.

A week after the accident, one of my closest childhood friends drove me down to Wakulla Springs. We stayed in the lodge that night, and I left early the next morning for New Orleans. That ride, too, is something of a blur. I know I stopped at a gas station just after dawn, and these giant green, leaf-like bugs—katydids—were all over the outside of the place. They seemed so sweet and gentle that morning, like sentient plants.

Later that day, I stopped at a gas station somewhere in the Big Bend of Florida and realized my chain was loose. I was sitting in the parking lot, trying to break the axle bolt free with an ancient crescent wrench, when a man with broken teeth appeared. I followed him to his rusted-out Ford, and he produced a fancy Snap-on ratchet set. He went inside for breakfast, where there weren’t even any windows to make sure I didn’t run off with his tools, and told me to come find him when I was done. I can’t tell you how much that meant to me.

The next day, I made it to my aunt’s house in New Orleans, where my dad always stopped on his long rides, and Blitzen broke down right there in her driveway, as if the machine knew just how much it meant to me to finish the ride for him.

He may have left the world too early for us, but I take some comfort in knowing my old man would have wanted to go too soon rather than too late. Rick Brown would have wanted to die with his boots on, and he did. He died doing what he loved, and that is rare indeed.

These days, I’m more vigilant than ever on the bike. I know the risks. It’s a serious decision for me to ride, every time. But there’s no place I feel closer to my dad. I think of him every time I throw my leg over the saddle. I think how much I learned from him, how lucky I am to be his son. I think how all those stories of his past, though marvelous, paled before the everyday dignity of the man, the quiet power of his character, and the grand size of his heart. Most of all, I think of the final words of the letter he left behind:

“I hope that I will always be part of your life, and that I can always be a whisper in your mind.”

You are, Dad. You are. I love you, old man, and I always will.