Southern Heroes

Wendell Berry: The Poet of Place

A conversation, in letters, with one of the South’s most vital voices

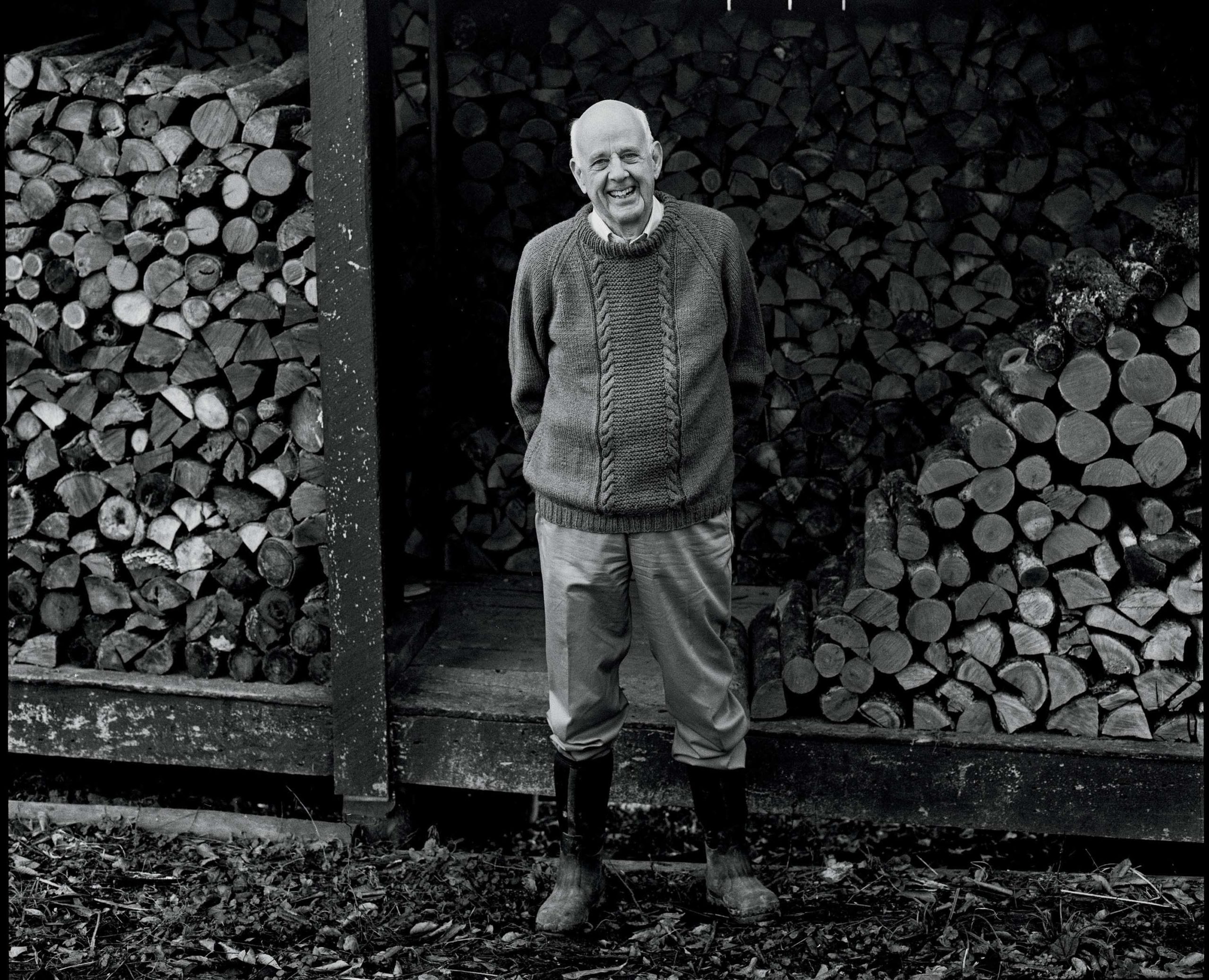

Photo: GUY MENDES

Berry at home on Lanes Landing Farm in Port Royal, Kentucky.

Wendell Berry has been called a prophet and a visionary, but he has about as much use for such lofty praise as he does for screens. He doesn’t own a cell phone or a computer. An essayist, fiction writer, poet, and small-farms advocate, Berry does possess a National Humanities Medal, which President Obama presented him in 2011, as well as a slew of other honors and the adulation of people around the world who admire him not only for his tremendous body of work but also for his activism and uncompromised truth telling.

Since his debut in 1960, he has published prodigiously. “Let’s say a lot. Or: too many,” Berry says, when asked how many books he has written. Among his works are masterpieces such as his poem “The Peace of Wild Things,” his novels Jayber Crow and Hannah Coulter, and hugely influential non-fiction such as What Are People For? and Home Economics. He is currently working on a new book that his publisher says may be seen as an update of his 1977 classic, The Unsettling of America.

Now eighty-five, Berry lives in Henry County, Kentucky, where he was born and raised, having resettled there in 1964 after stints in California and New York City. He is beautifully devoted to his wife, the artist and agrarian Tanya Berry, and says that a perfect day for him involves writing and farming, both of which he does on his property overlooking the Kentucky River, where I recently spent the day with him and saw firsthand his knowledge of the land, its history, and its people. For this conversation, however, we wrote to each other in mailed letters and then had early-morning telephone chats, a process that illuminates Berry’s insistence on looking at everything—trees, rivers, words, discourse—with deep care and interest.

What are some ways that poetry can save us or at least provide a balm?

The proposition “that poetry can save us” is so general and dramatic that my instinct is to back away to a safe distance. And then I see that the question implies, and I agree, that poetry, like all the arts, has an obligation to “us,” if not to save us, then to help to save us. The nearest platitude about this must be Mallarmé’s idea that a poet’s contribution or duty, as usually translated, is to “purify the language of the tribe”—or, to quote him exactly, “to give a purer sense to the words of the tribe.” Maybe we can start with that.

Why does the language of a tribe, or any community, need to be purified? I will answer for myself that the prescribed duty is to keep the language capable of telling the truth. My education advanced a long step when I learned from Ezra Pound that the Chinese ideogram for “fidelity to the given word” shows a man “standing by his word.” To stand by one’s word is everybody’s duty. To make words precise enough and clear enough to be stood by also is everybody’s duty, but I think that that has got to be the paramount duty of every writer, not just of every poet.

We can think of writers as people under obligation to produce exemplary language. But another kind of language that has been exemplary for me is, or was, the language of the fairly settled agrarian communities I grew up in. This was a language full of the names of people, places, tools, and kinds of work that were the common knowledge of a few hundred people living together over a long time. Farming neighbors working together must be capable necessarily of speaking precisely and clearly, and they are necessarily expected and obliged to stand by their words. (Some people of course were liars, but these were known, allowed for, often quoted, and much enjoyed.) A major part of my schooling as a writer came from the conversation of “uneducated” farmers.

One of the things I’ve noticed the most in my lifetime is the loss of community. How do we reclaim that?

This we have in common, because we both are rural Kentuckians and rural Americans. Rural America is a country much noticed by liberal commentators since the election of President Trump. They are right at least in seeing that, in comparison with urban America, rural America is poor. Rural America is poor because for a long time the higher-ups of wealth and power have happily sacrificed the ecological and economic health of rural America in order to supply cheap food, cheap energy, cheap “raw materials” of all kinds, to the people, and mainly the wealthier people, of urban America. And so our communities have declined mainly for economic reasons: They are too poor to employ their young people at home, their necessary small businesses have been destroyed by the likes of Wal-mart and Kroger, and social fashion for a long time has preferred the city and scorned the country.

The difficulty is that communities can cohere and thrive only as coherent and thriving local economies. People in small rural communities need their own small businesses, stores, workshops, legal and medical services, schools, and churches. People become neighbors by working together, talking to each other, and needing each other’s help and encouragement and comfort.

What can we do? We can take Gary Snyder’s good advice: “Stop somewhere.” He meant stop and stay and deal with the consequences. We can teach ourselves to think as community members rather than as individuals in competition with all other individuals. We can work, shop, eat, and amuse ourselves as close to home as possible. We can, on our own or with like-minded people, become mindful of all that we have in our places that is worth keeping, and of the best ways of keeping those things. And, to quote Gary Snyder again, we can

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

Food is a big part of community. I remember you telling me one time that you and Tanya try to always sit down to eat together three times a day. Why is that important?

I think that coherent communities, when our people had them, were made up of coherent households. In about all the households I knew as I was growing up, the kitchen table was a sort of first principle of family order. Wherever they went between meals, everybody came in and sat down at that table for breakfast, dinner, and supper. And so it is important to me, a major theme continuing through my life, that Tanya and I still sit down at our kitchen table and eat together—though as we have got older, our suppers have dwindled to snacks. That shapes the days in a way dearly familiar and is a comfort. Also I like the company.

Do you and Tanya eat out of local gardens and preserve food so you’re able to eat locally through the winter?

When we moved here and stopped, fifty-six years ago, we wanted to make our household economy as complete as our small acreage and our work could make it. And so, especially during the years when our children were with us, we raised a garden, milked a couple of cows, kept a flock of hens, and slaughtered a calf and two hogs every year. And we, mainly Tanya, canned and froze and cured enough food to take us through the winter. We ate a good many meals of which nearly everything but the salt and pepper had come from our place. By now of course we have been changed by years and wear, and our use of our place is much reduced from what it was. Now we get meat from family and neighbors, and we get a lot of our vegetables from neighbors who raise table crops for sale locally.

I know you spend a lot of time outdoors on your farm, but I’m also wondering if you actively observe and think better while outside.

I’ve always liked to work outdoors and to be outdoors. Having even so marginal a farm as ours, with farm animals, requires me to be at least a while outdoors every day in all kinds of weather. I have needed that.

When I was young, I picked up some expert’s advice that a writer needed to write facing a bare wall so as not to be distracted. And so I tried writing in a library carrel, in which I was constantly distracted by the suspicion that I was missing something interesting that was probably taking place elsewhere. For me, that didn’t work. To write I’ve always needed at least a big window, in warm weather a porch, on a day that is warm and dry a good sitting place in the woods. I suppose I’ve needed something of interest to look up at.

But I think my work also has benefited from distractions. There are times when my writing has had to come second to my family or my neighbors or my horses or my sheep. These reminders of things more important than writing have kept my writing firmly placed in the workaday world, where it belongs.

When someone says “the South,” what is the main thing that comes to mind for you?

“The South,” that phrase, if you want to use it intelligently, calls for a lot of caution and care. As a name strictly geographic, it refers to a section of the country below the Mason-Dixon Line and the Ohio River, and as far west as Texas. Geographically that makes fairly exact sense. “Fairly” exact because the geographic sense is defined also by history: “The South” refers to the “slave states,” and so the term excludes New Mexico and Arizona. But among the slave states are the “border states,” Kentucky being one, which are slave states that did not secede from the Union during the Civil War.

More care is required to understand that “the South” is not “a place,” but rather a collection of places, varyingly different from one another, each with its own geography, history, economy, mix of people, climate, and weather. Kentuckians would be quick to point out that Kentucky is not Florida or Georgia or Texas or even Tennessee. And Kentuckians have reason to be sensitive about this, because their own state contains a number of regions significantly unlike one another. To respect these differences is both honest and courteous.

The most serious trouble begins when “the South” is used as a sort of symbol standing for racism, slavery, the Confederacy, Jim Crow, and related problems. This usage leads, of course, to the use of “Southerners” as a synonym to such pejorative terms as “racist” and “redneck”—thus implying somewhat dangerously that there are no racists or rednecks in “the North.”

As Southerners at least are likely to know, racism and sexism are not the only prejudices.

You’re very much associated with Henry County. Most people’s identities are not so tied up with a particular place. Do you have a reaction to that?

In fact, I don’t feel “associated” with all of Henry County. The part of it that I intimately belong to, my home country, is a sort of corridor running from New Castle to the Kentucky River below Port Royal, in the watersheds of Emily’s Run, Cane Run, and Town Branch of Drennon Creek. That is the country I rambled and swam, and fished and hunted in when I was a boy. It contains all the farms I have worked on and know best.

My reaction, I guess, must be some surprise and a lot of comfort in realizing how endlessly instructive and enriching my knowledge of so small a scrap of country has been and still is.