Southern Masters

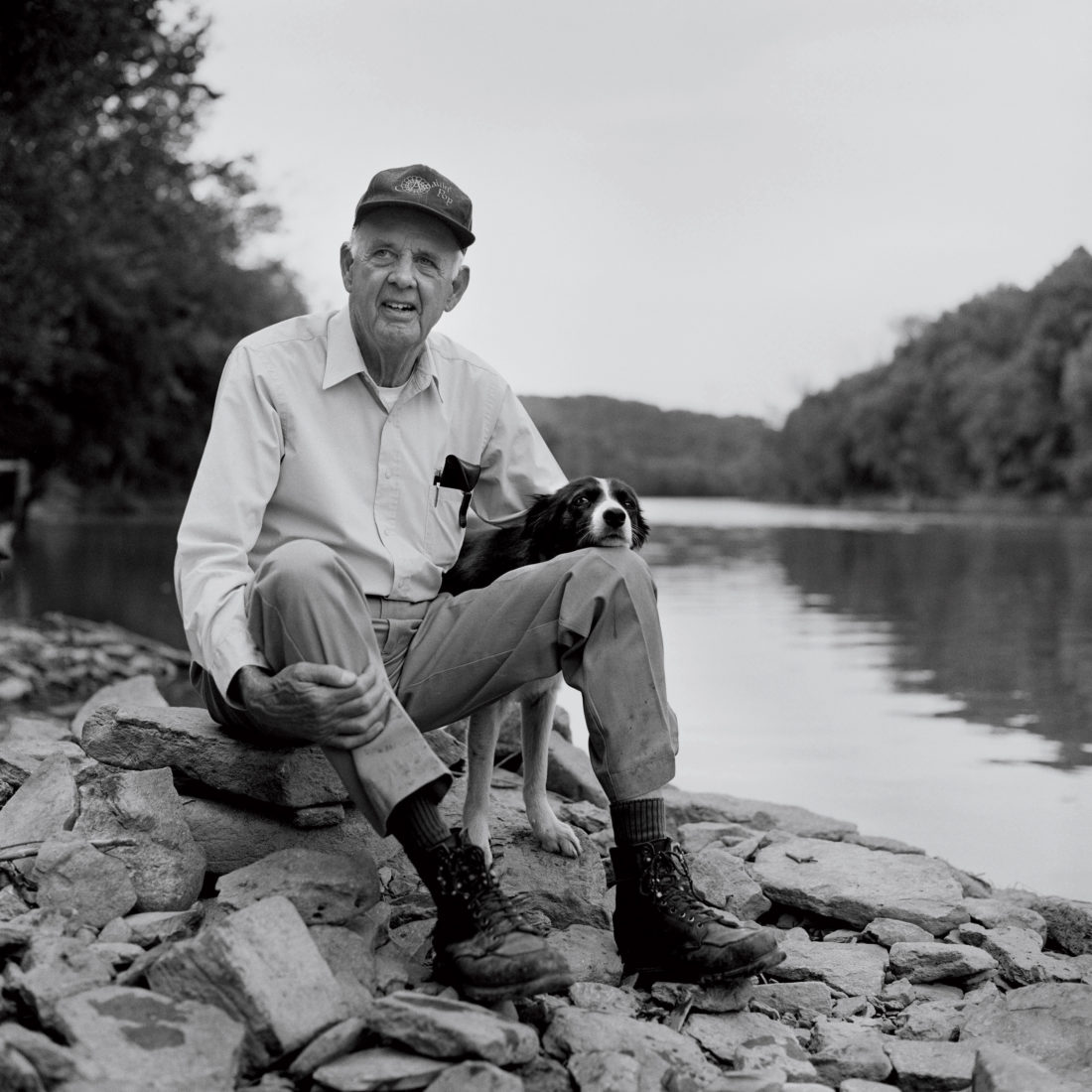

Wendell Berry’s Wild Spirit

Counting songbirds and talking about the land with the legendary conservationist, farmer, and writer

Photo: Guy Mendes

“I began to see, however dimly, that one of my ambitions, perhaps my governing ambition, was to belong fully to this place, to belong as the thrushes and the herons and the muskrats belonged, to be altogether at home here….”

It is eight in the morning on the last day of the world. We are standing, six of us, alongside the county road that cuts across Wendell Berry’s farm near the small Kentucky town of Port Royal. To our right, the Kentucky River has retreated back inside its banks after a tempestuous spring. In the lower pasture, a single llama guards Wendell’s sheep against coyotes. Up on the hill to our left stands the Berrys’ traditional white farmhouse as well as several busily occupied martin houses. The birds are what bring us here each May, but radio preacher Harold Camping’s doomsday prediction that the world will end tomorrow, May 21, has lent today a kind of cosmic, I mean comic, significance. “Well,” Wendell says, wearing khaki work pants and a team sweatshirt from one of his granddaughters’ high schools, “if this is our last day, we might as well have as much fun as we can.”

“No better place to do that,” says botanist Bill Martin, and we all nod our agreement. Besides Bill, our coterie consists of wildlife biologists John Cox and Joe Guthrie, me, Wendell, and his retired neighbor, Harold Tipton. Wendell, Bill, and Harold are of one generation; John, Joe, and I are of another. Some semblance of this group has been congregating here for the past eight years. The official nature of our business is to count and identify birds—migratory warblers and summer residents. But our pursuits might better be described in terms of what Wendell calls a “scientific quest for conversation.” As much as anything, we come to hear and to tell stories.

Wendell has been telling the story of this land for nearly five decades. A few hundred yards upstream from where we have gathered stands his writing studio, an approximately sixteen-by-twenty-foot room that overlooks the river and was the subject of an early essay, “The Long-Legged House.” Sitting atop tall stilts, the “camp,” as Wendell calls the studio, slightly resembles a great blue heron standing silently on the riverbank. It has no electricity, but natural light flows in through a large window, over a long desk where Wendell has written more than fifty books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and in the process has become known as a leading writer on the subjects of conservation and land stewardship. “It is a room as timely as the body,” Wendell wrote in a recent poem:

As frail, to shelter love’s eternal work,

Always unfinished, here at water’s edge,

The work of beauty, faith, and gratitude

Eternally alive in time.

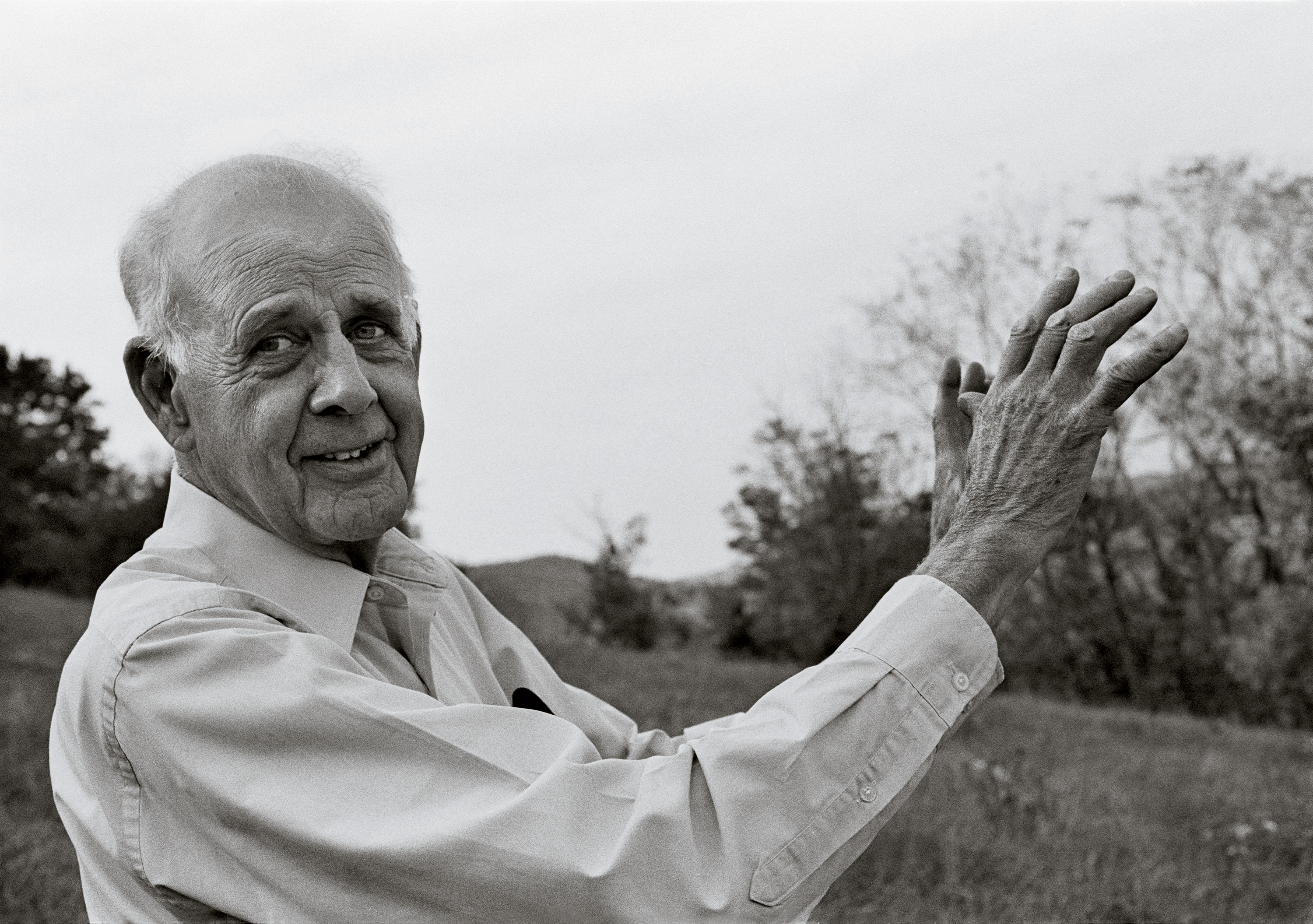

Photo: Guy Mendes

Wendell Berry in Henry County, Kentucky.

In tumultuous and uncertain times, it is worth being reminded that these fine things—beauty, faith, gratitude—still lurk eternally beneath history’s dark veneer, and that an artist working alone in a room beside a river may catch a glimpse of them and render them into a lyric poem, a short story, or an essay.

Photo: Guy Mendes

Berry receiving the National Humanities Medal.

Because of that work, President Obama awarded Wendell the National Humanities Medal in March at a White House ceremony. As he was presenting the award, the president told Wendell that reading his poetry had helped improve his own writing. It is an impressive remark, given that Obama is one of the best writers, along with Jefferson, Lincoln, and Grant, we’ve ever had as president.

For today’s excursion, we load into Wendell’s pickup and drive a few miles to Harold’s farm. A green heron is wading in the creek that runs alongside the road. John and Joe, who are the group’s best birders, identify the songs of thrashers, kingbirds, and waterthrushes as we pass through these lower reaches. Then Wendell’s reluctant truck climbs a nearly washed-out road until we pull into a field in front of a log cabin, hewed out of large oak logs in the 1800s. Wendell’s wife, Tanya, and Harold’s wife, Ida, have sent along lunch for us. Harold stows our provisions inside the cabin, and the six of us, each armed with a pair of binoculars, set off through high grass and occasional ironweed. Phoebes, towhees, and prairie warblers are singing in the trees at the edge of this meadow. Joe records their names in a small notebook. Having no destination, only this will to wander, we move slowly. What’s more, Wendell announces that in response to our culture of instant messaging, he has just founded a new cause, the Slow Communication Movement. Certainly we embody that spirit today, and it feels good. It is a more leisurely, more deliberate form of communication, and it isn’t limited to 140 characters.

At seventy-seven, Wendell is unapologetically out of fashion, though there really never was a time when this wasn’t true. A friend of his, the writer Ed McClanahan, tells the story that, years ago, when Wendell’s agent called excitedly to say Robert Redford was giving as Christmas presents copies of Wendell’s landmark book The Unsettling of America, Wendell turned to Tanya and said, “Queeny, who the hell is Robert Redman?” He famously doesn’t own a computer and has written all of his books in longhand.

And yet, after the economic collapse of 2008, Rod Dreher of the Dallas Morning News wrote a column arguing that, in such a moment of crisis, it was finally time we listened to, of all people, Wendell Berry. It was Wendell, he argued, who “stood steadfastly for fidelity to family and community, self-sufficiency, localism, conservation and, above all, learning to get by decently within natural limits”—in other words, all of the things that could have staved off a financial crisis driven by rapaciousness and centralized power. The point is that progress doesn’t move inexorably in one direction, toward a technological future, and it doesn’t always look like progress. In an age of toxic agribusiness and climate crisis, it might look more like a family farm, powered by sunlight.

To make this point, and more specifically to protest the mountaintop-removal strip mining that is destroying eastern Kentucky, Wendell joined in a sit-in at Governor Steve Beshear’s office in February. The protesters’ plan was to get arrested and call attention to the cause, but the governor’s staff quickly realized it didn’t want any pictures of Wendell in handcuffs hitting the papers. So no one was arrested and the protesters spent the weekend in the capitol building, before emerging on Monday to a rally of supporters.

Photo: Guy Mendes

Camping out at the governor’s office.

Knowing Your Place

We stop at a lone honey locust tree standing in the middle of the field, and Wendell calls our attention to its mildly fragrant catkins. Bill holds up a small magnifying glass to the tiny flowers. Such is the nature of this outing—trying to pay attention to the things most of us ignore or simply don’t take the time to notice in our daily comings and goings. To see the natural world, after all, either through a magnifying glass or a poem, is the first step toward wanting to preserve it. John points to a song in the crown of the tree and says, “Flycatcher.” Joe writes that down.

We walk on, past a thicket where two male indigo buntings, flashing like the bluest shards of stained glass, duel over a female hidden in the brush. Then we stop to watch an orchard oriole (much rarer than the Baltimore variety), perched above the swirling buntings.

Wendell is speculating on the brain of a bird, on what a bird can know. “It has the intelligence to adjust its archetype to its place,” he finally decides.

“You mean its environment,” Bill says.

“I don’t use that word,” Wendell replies. “It’s an abstraction. It separates the organism from its place, and there is no such place.”

“Well, what do you say then?” demands Bill, who likes to needle Wendell.

“I name an actual place. I say Harold Tipton’s farm.”

Photo: Guy Mendes

Birding in Kentucky.

It was in fact this attention to the particular that prompted our first walkabout. Eight years ago, a colleague of mine at the University of Kentucky, Dave Maehr, suggested to Wendell that he should catalog all of the migratory songbirds that passed through his farm each spring. Wendell liked the idea very much, and we spent the first few years walking those wooded slopes and fields, set only a few miles from where Wendell was born, in 1934.

His father was a country lawyer who helped start the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative Association during the Depression—an act that was instrumental in keeping small farmers on their land. In 1958, Wendell went off to Stanford to study writing with Wallace Stegner, then in 1962 he accepted a teaching position at New York University. After a few years in the city, he was ready to come home, back to Henry County. Friends in New York advised him against it; they said returning to Kentucky would be literary suicide. “But I never doubted that the world was more important to me than the literary world,” Wendell wrote in his early essay “A Native Hill,” and so he and Tanya bought Lanes Landing Farm in 1965. Wendell worked the farm, raising tobacco, cattle, and later Highland sheep.

Back in Kentucky, Wendell wrote, “I began to see, however dimly, that one of my ambitions, perhaps my governing ambition, was to belong fully to this place, to belong as the thrushes and the herons and the muskrats belonged, to be altogether at home here…. It is a spiritual ambition, like goodness. The wild creatures belong to the place by nature, but as a man I can belong to it only by understanding and by virtue.” To know a place intimately means to belong to it more fully, and to take responsibility for its preservation.

One year on Wendell’s farm, at the peak of the neotropical warbler migration, we counted more than one hundred different birds. Each year, Dave Maehr would type up the list and send a copy to Wendell, who in turn encouraged Dave to take up a more activist stance toward irresponsible logging practices in Kentucky. Dave responded, and in doing so made some enemies within his own forestry department at UK. As a wildlife biologist, he studied large mammals, or “charismatic megafauna,” of which Dave was certainly one demonstrative example. He was brash and voluble and generally considered the country’s leading expert on the Florida panther. I could tell Wendell found him to be very good company indeed.

Then, one Sunday morning a month after our fourth excursion to Wendell’s, I picked up the Lexington paper to read that Dave was dead. He had been down in Florida, conducting an aerial survey of black bears, when the single-engine plane he was in stalled, then nose-dived, killing Dave and his pilot instantly. We were all stunned, and John, his student and best friend, certainly took it the hardest. A few months later, Wendell wrote me a letter suggesting that we could best honor Dave’s memory by continuing our annual avian rite of spring, and that we should give it a name: the Dave Maehr Memorial Bird Walk.

The Best Noise in the World

So here we are, this time up at Harold’s farm, honoring Dave with our peripatetic ritual of walking the fields and forests of Kentucky. It reminded me of another passage from one of Wendell’s poems:

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

This seems to me the fundamental premise undergirding all of Wendell’s work—that the natural world is sacred, not a “resource” to be desecrated by the extractive industries that fuel our economy. For more than forty years, Wendell has been telling Americans that we cannot survive the economist’s dream of infinite economic growth on a finite planet. And certainly some have listened. The Unsettling of America redirected the way we think about food and agriculture in this country to the point that the farmer’s market is currently the fastest growing part of the American food economy. But obviously not enough people have listened, and so Wendell keeps writing his jeremiads against industrial hooliganism, and he keeps writing his poems that fulfill what the philosopher Martin Heidegger called the role of poetry—to praise the whole in the midst of the unholy.

Our meanderings take us down a logging road shaded by oak and ash trees. Bill is telling a joke that involves farm boys and amorous sheep. When he gets to the punch line, Wendell’s laughter crescendos all around us, and I remember something the poet Jane Kenyon once said—that Wendell laughing is “the best noise in the world.”

That might come as a surprise to readers of Wendell’s polemical tracts, where humor is seldom on display. But Wendell seems to balance his justified sense of outrage at the industrial economy with the pleasure that he takes in the natural world he is fighting to preserve, and in the stories that perpetuate the human comedy.

The first year I came along on the walk, I felt anxious that I wasn’t nearly as good a birder as Wendell and the others. We were crossing a stream on Wendell’s farm when he suddenly turned to me, pointed skyward, and said, “You hear that, Erik?”

“Uh, well, I’m not sure, uh…what is it?”

“That’s the hairy-chested nut-scratcher!” he said, then slapped his thigh in a burst of laughter.

Now we dip farther down into an older forest, walking among spleenwort ferns and mayapple. The birds have grown quieter as the morning has stretched out, and Wendell has turned his attention from the sky to the ground. He bends down, brushes away some leaf cover, and starts digging with one hand. “Look how rich this soil is,” he remarks, then glances up as the rest of us watch him dig. “The way these old abused hills have been reforested is inexhaustibly interesting to me.”

The trees and the ferns and the wildflowers have formed a reciprocal community here on this hillside, based on natural laws that Wendell calls “mutualistic.” Nothing lives here in isolation.

“That’s the problem with modern science,” Wendell begins, rising up. “It isolates a problem and offers an isolated solution. To the problem of depleted soil it offers nitrogen fertilizer. And the problem with that is a huge dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico because of all that nitrogen runoff.”

Conversely, the solution to that botched solution is to better observe the workings of the natural world. For that reason, Wendell often points to the visionary experiments of his friend Wes Jackson, who at the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, is creating a new kind of perennial agriculture that mimics the workings of the Midwestern prairie.

“Look at all this,” Wendell says, standing and gesturing to the trees. “This isn’t wild. This is domestic. What’s wild is what’s out of control. That’s what we mean by wild. And we are the ones that are out of control. We are the ones creating that dead zone.”

Wendell probably knows he is preaching to the converted, but he also probably knows that one reason we come down each spring is to hear what’s on his mind.

Of course, because of such talk, critics have often dismissed Wendell’s writing as “naive.” He knows this well enough and has a reply for defenders of the status quo: “The word inevitable is for cowards.”

It is nearing noon and Joe’s list has almost reached sixty. We start back toward the cabin, where Harold soon has a pot of barbecue simmering. We heap portions of it onto sandwiches, then take our seats in the center of the cabin’s one room.

The barbecue is delicious, the company fine, the weather perfect. All of this seems to inspire Wendell to reveal his plans to found another subversive cabal: the Society for the Preservation of Tangibility. The tangible—that which has actual form and substance. In a culture of avatars, electronic friends, and financial “products” that have no basis in reality, such a fundamentally human society sounds attractive indeed.

We all immediately ask if we can join. “Anyone can join,” Wendell replies. “There are no dues, no meetings, no fund drives, no newsletter.” There is only a state of mind, a desire to preserve what’s authentic, what holds substance, what aspires to the whole.

The possibility that a broken world can be made whole seems to be what calls Wendell down to his riverside desk every day. “A man cannot despair,” he once wrote, “if he can imagine a better life, and if he can enact something of its possibility.” To imagine—it is perhaps the most powerful moral force we possess because it maps a future that is worth finding. It has been Wendell’s life’s work.

Outside the cabin door, a Carolina wren starts to sing.