Pandemic cooking has made stars out of forgotten kitchen staples, especially the humble bean.

Ryan Hacker was only a few months into his new job as executive chef at the beloved French Quarter fixture Brennan’s Restaurant when New Orleans closed its dining rooms. “I never had this much time at home before,” he says. While he helped plan for reopening, he spent time teaching his two young daughters to cook family recipes. One of them was soup beans, a simple one-pot meal that over the years he has transformed into something he has nicknamed Southern cassoulet, after the French meat-and-bean stew.

Often associated with Appalachia, soup beans—traditionally long-simmered pinto beans sometimes bulked up with a little meat—have been an economical go-to of many Southern kitchens. Hacker ate his first bowl while growing up just outside Tyler, Texas. Pinto beans would go into the slow cooker with some sausage and onions. One batch could feed the whole family for a couple of days. When he got to college, soup beans provided an inexpensive way to stay fed on a student’s budget. Even after landing an internship at Hamersley’s Bistro in Boston, he relied on them. “I was making cassoulet every day at the restaurant, but I barely had enough money to make it to work and back,” he says. The French stew inspired him to add a little inexpensive white wine to his own beans and to top them with crunchy bread crumbs.

His recipe evolved again after he married his wife, Malorie, who had Southwest Texas roots. She grew up eating frijoles charros, which had more pork and were brightened with tomatoes and jalapeños. After the young family landed in New Orleans, he took to adding a dice of bell pepper and celery with the onion (the holy trinity) and andouille sausage. “Now you look at it, and it’s nowhere near a traditional soup bean recipe,” he says. “But it’s the story of me.”

While the beans cook, it’s essential to keep adding enough water so they stay soupy. Hacker likes to serve them over a hunk of cornbread to soak up the liquid and finishes the dish with a buttery, crunchy layer of seasoned cornbread crumbs. By the second day, he says, the beans will have turned creamy and the meat even more luscious. “Once the meat is gone, we like to turn whatever’s left into refried beans. That’s what’s so great about beans. They just keep on giving.”

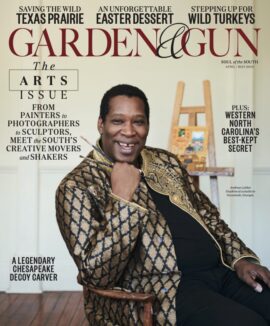

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.