Arts & Culture

Delivering ‘Deliverance’

An oral history of one of the most unforgettable Southern movies of all time

Illustration: Steve Brodner

James Dickey was the kind of man who made Ernest Hemingway look like a florist from the Midwest, says his former student the writer Pat Conroy. Dickey’s book Deliverance was one of the hottest things on the stands, a literary triumph. The novel tells the story of four Atlanta suburbanites and “the weekend they didn’t play golf,” as one of the movie posters later said. Instead, they decide on an excursion into the North Georgia wilderness that changes their lives. A canoe trip down the white waters of the fictional Cahulawassee River puts them smack-dab in the middle of backwoods hell. They have to fight their way out, but not before one of them is raped and another dies. When Hollywood released the movie version in 1972, for which Dickey also wrote the screenplay, it became one of the signature—and most shocking—films of the decade.

Dickey’s poetry made him famous, the nation’s poet laureate. But Deliverance catapulted him into the stratosphere, where he was toasted all the way from The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in Hollywood to the presidential inauguration in 1977. For decades, the themes of the story had haunted the native Georgian. It started with canoe and hunting trips in the 1950s. “I love the woods and I love wild nature,” he said in a short studio documentary produced to accompany the film’s release. He envisioned a battle between man and nature in which man summons within himself courage he never knew he had.

During the summer of 1971, Deliverance came to life just a little more than a hundred miles northeast of Atlanta. There in Rabun County, an adventurous director and cast plunged into the rapids of the Chattooga River to capture Dickey’s masterwork. But our story begins in 1961, when Dickey was working at the Atlanta advertising agency Burke Dowling Adams. When he wasn’t writing, he was at the Bitsy Grant Tennis Center.

I. THE NOVEL

John Logue (a friend of Dickey’s and former managing editor of Southern Living): I was a sportswriter for the Atlanta Journal, making seventy-five dollars a week. In my off hours, I was looking for a game, and here comes this husky guy—James Dickey. We began to play tennis. One day he said, “I’m quitting my job.” I said, “What are you going to do?” He said, “I’m going to be a poet.” And I said, “Dickey, I’m not buying the tennis balls.”

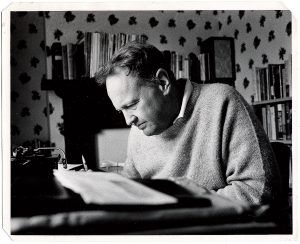

Photo: James Dickey Papers, Manuscript, Archives

Author James Dickey at work in his study.

JAMES DICKEY*: I do feel what the French writer Henry de Montherlant says, “If your life ever begins to bore you, risk it.”

*All quotations from the late James Dickey taken from Bill Moyers’ Journal: A Conversation with James Dickey, aired January 25, 1976, on PBS (produced by South Carolina ETC).

JOHN LOGUE: The guy who got him going down rivers played tennis with us. His name was Albert Braselton, and he always had old worn-out shoes. I thought, Either he’s a guy who was working for the government and could get off anytime he wanted, or he didn’t have much money. It turns out that he had a ton of money.

JAMES DICKEY: The affluent society has created a state of boredom, which can only be characterized by the word crushing. People will do anything to get out of it.

JAMES DICKEY: The affluent society has created a state of boredom, which can only be characterized by the word crushing. People will do anything to get out of it.

JOHN LOGUE: [Dickey] got a Guggenheim Fellowship to Italy, and while he was over there, he was writing all the time.

CHRISTOPHER DICKEY (James Dickey’s oldest child and the author of the memoir Summer of Deliverance): He first got the idea beneath the cliffs of Positano [in Italy] in the spring of 1962. He would watch in envy as a couple of proto-hippies would free-climb the cliffs there. A young literary agent named Theron Raines sent him a letter asking whether he thought he could write a novel drawing on the setting and imagery of his prize-winning poem “Springer Mountain,” and he started turning over in his head the basic narrative.

PAT CONROY (writer and Dickey’s student at the University of South Carolina): I got into his class the year after Deliverance came out. He was so smart and erudite he made you want to go out and eat a book of poetry. I thought Deliverance was one of those perfectly made novels. He seemed to bind up and connect his talent for poetry. I remember the scene where Ed climbs up to try to encounter the mountain man at night. I’m thinking, You can’t write much better than this.

T. C. BOYLE (novelist and short-story writer): Deliverance was brilliant. It’s influenced me thematically because I’m often writing about man and nature, man against nature, and this whole atavistic spiral that Dickey shows us.

PAT CONROY: My friend Terry Kay is a novelist from North Georgia, and he was furious with Dickey’s book. He said, “He didn’t write about your people, Conroy. He’s writing about my people.” I said, “Look, all he said was your people had no teeth, they were dumb as shit, they never bathed, they were all retarded but could play the banjo. Otherwise, he didn’t say anything bad about your people. They’re just like you, Terry. I recognized them immediately.” So Terry, who’s got this great Churchillian voice, replied, “Conroy, let me tell you one thing: You can go up to the mountains with my people and we may kill you, but we’re not going to f*** you.”

II. HOLLYWOOD COMES CALLING

In 1970, a former student of James Dickey’s named David Giler was working at Warner Bros. He got an advance copy of Dickey’s novel and encouraged studio executives to acquire the film rights, which they did, paying “an absurdly high figure for it,” as Dickey wrote to a friend in April 1970. The overall deal—worth more than $100,000 ($610,000 in today’s money)—also permitted Dickey to write the screenplay and interview filmmakers. He cooled on The Wild Bunch director Sam Peckinpah and Rosemary’s Baby’s Roman Polanski. But when he met the Englishman John Boorman, he believed he’d found his man. In December 1970, Dickey wrote to Boorman, “We are going to make a hell of a movie.”

DAVID GILER (former student of Dickey’s and a film writer and producer): I first heard him when he was teaching at San Fernando Valley State College in the 1960s, and was blown away by his lecture. He was a force in person—a giant, and not just physically. He told me about Deliverance, and I thought it would make a good motion picture.

JOHN BOORMAN (producer and director): I had made Hell in the Pacific with Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune under very difficult circumstances in the South Seas. We lived on a ship anchored off this island where we shot it, so I think Warner Bros. felt I was the kind of man to take on a very physical picture.

The first place I met Dickey was at his house. He said, “I’m going to tell you something I’ve never told a living soul, and I want you to promise not to mention it to anybody: Everything in that book happened to me.” Of course, I couldn’t wait to tell someone. I was there with my associate producer, Charles Orme, and as soon as we left the house I said, “Do you know what he told me? That everything in the book happened to him.” And Charles said, “Yes, he told me the same thing.” Dickey told everybody that story.

JOHN LOGUE: Dickey was mischievous from the first day I ever knew him. We went to eat at a Japanese restaurant, the kind where they chop everything up. The chef chopped-chopped-chopped right near Dickey and, all of a sudden, it looked like the end of Dickey’s finger popped into his vodka, bleeding. Dickey screamed and the chef almost fainted. Well, Dickey had taken a shrimp and dipped it in ketchup and just as the guy chopped near him, Dickey flipped it in his drink. That was typical Dickey.

CHRISTOPHER DICKEY: Dad wanted to write screenplays that could be published as books, or at least in books, as some of [the writer] James Agee’s had been.

JOHN LOGUE: I was visiting and sleeping in his guest room and he stuck his head in and threw this manuscript on my bed. It was the

screenplay. I sat up and read the whole thing.

JOHN BOORMAN: It wasn’t a screenplay as what we think of as a screenplay. He’d just filleted the book.

RONNY COX (actor, Drew Ballinger): Apparently the screenplay is like seven hundred pages long.

JOHN BOORMAN: The first third of the book describes the four men in Atlanta, living comfortable lives. Dickey felt that the film should spend the beginning depicting that. I took the view that you can’t do that in a film. Through action and behavior they define themselves. That’s the nature of film—character, action, definition. That was our first big disagreement—and I prevailed.

GORDON VAN NESS (Dickey scholar and friend; professor of English, Longwood University): Jim was far more concerned with lighting and the angle shots, to give the film a poetic quality. Action was important only so far as it reinforced themes. Boorman was not going to do that at all.

CHRISTOPHER DICKEY: Boorman had a much better sense of how to put a film together.

III. ASSEMBLING THE CAST

Several actors were discussed to play the leads, including Lee Marvin and Gene Hackman. But Boorman eventually focused in on two names.

JOHN BOORMAN: Warner Bros. wanted two major stars, so I went to Jack Nicholson [to play Ed]. He agreed to do it and asked, “Who will you get to play Lewis?” I said, “I don’t really know yet.” He said, “What about Brando?” So I went to see Marlon Brando—spent the day with him. Finally, he said he’d do it. I asked, “Who’s your agent?” He said, “I don’t have an agent.” I said, “Well, what’s your price?” And he said, “I’ll take the same as you pay Jack.” I went back to Nicholson’s agent and said, “What do you want for Jack?” He said, “Half a million.” Now, Nicholson had never got more than $75,000. So I told studio head Ted Ashley. “Brando? Oh, God. He doesn’t mean anything anymore—he’s box-office poison.” Well, I thought Nicholson and Brando would work very well together. Ashley asked, “What does Jack want?” I said, “Well, he wants half a million.” “Half a million?!” Ashley almost went through the roof. Then he kind of calmed down and said maybe they would pay him that money because everyone in town wanted Nicholson. He said, “What does Brando want?” “I agreed to pay him the same as Jack.” Ashley then exploded, “I’d be laughed out of this town if I paid half a million for Brando.” I said, “Look, you asked me to get two stars. I got them. Now you’re saying you don’t want to pay them. What happens now?” He said, “Well, you make it for a price, go with unknowns, and let’s see what happens.”

RONNY COX: I was in New York, struggling as a stage actor. They came to town looking for unknown actors and, God knows, I was unknown.

LYNN STALMASTER (casting director): The first person we cast was Ronny to play the character of Drew. Ned Beatty was performing at the Arena [Stage] theater in Washington, D.C., and I called him and said, “You’ve got to make yourself available.” We wanted him for the character of Bobby, who gets raped. Ned had no problem with the sodomy aspect—some actors did.

Photo: Courtesy of Everett Collection

The Main Players

The four canoeists, played by Ned Beatty, Reynolds, Ronny Cox, and Jon Voight, before they depart.

NED BEATTY (Bobby Trippe): I was talking to John Boorman, who was in England, and I said, “Are we going to fake it or are we going to do it?” And he said, “We’re going to act it. It’s going to be an acting thing.” I said, “Fine, I can do that.” That was the entire conversation about that as far as I can remember.

RONNY COX: It was not only my first film, but my first time in front of a camera. It was Ned’s first film, too. We had done like twenty-some plays together. They didn’t even know we knew each other.

LYNN STALMASTER: Ultimately, John Boorman zeroed in on Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds for the leads.

JOHN BOORMAN: Burt Reynolds had done three unsuccessful TV series. I wasn’t aware of this because I didn’t live in America. Warner Bros. threw up their arms in horror.

IV. MEETING THE MAN

The stars, along with Dickey, checked in at the Kingwood Country Club in Clayton, Georgia, where they stayed during rehearsals, except for Beatty, who was finishing his run at the Arena Stage.

BURT REYNOLDS** (Lewis Medlock): [My character] was a very kind of physical guy. Dickey’s about six foot three and weighs about two thirty, and I think he expected me to be much bigger than I was. I did a lot of standing on chairs and things when he came around.

**Burt Reynolds is quoted from his appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, aired December 7, 1971, on ABC.

JAMES DICKEY: The character of Lewis has a baleful fascination for the other kind of soft-jowled suburbanites that he leads into the expedition. He’s full of pseudo-philosophical platitudes—“I think the machines are going to fail. I think the system is going to fail. And there’s a few men who are going to take to the woods and they’re going to start the whole thing over again.” These people who work in counting houses and advertising agencies and insurance firms have never heard anybody talk like that before.

RONNY COX: The day I arrived in Atlanta, the driver who picked me up said, “Jim Dickey is having a poetry reading this afternoon for some society. Would you like to go?” I thought, Oh, God, yes. They snuck me into the back of the room. Well, have you ever heard Jim read poetry? Amazing, amazing. He was this mountain of a man in this redolent Southern accent, holding forth. He read this one line and then sort of stopped and looked up and said, “God damn, that’s a good line.”

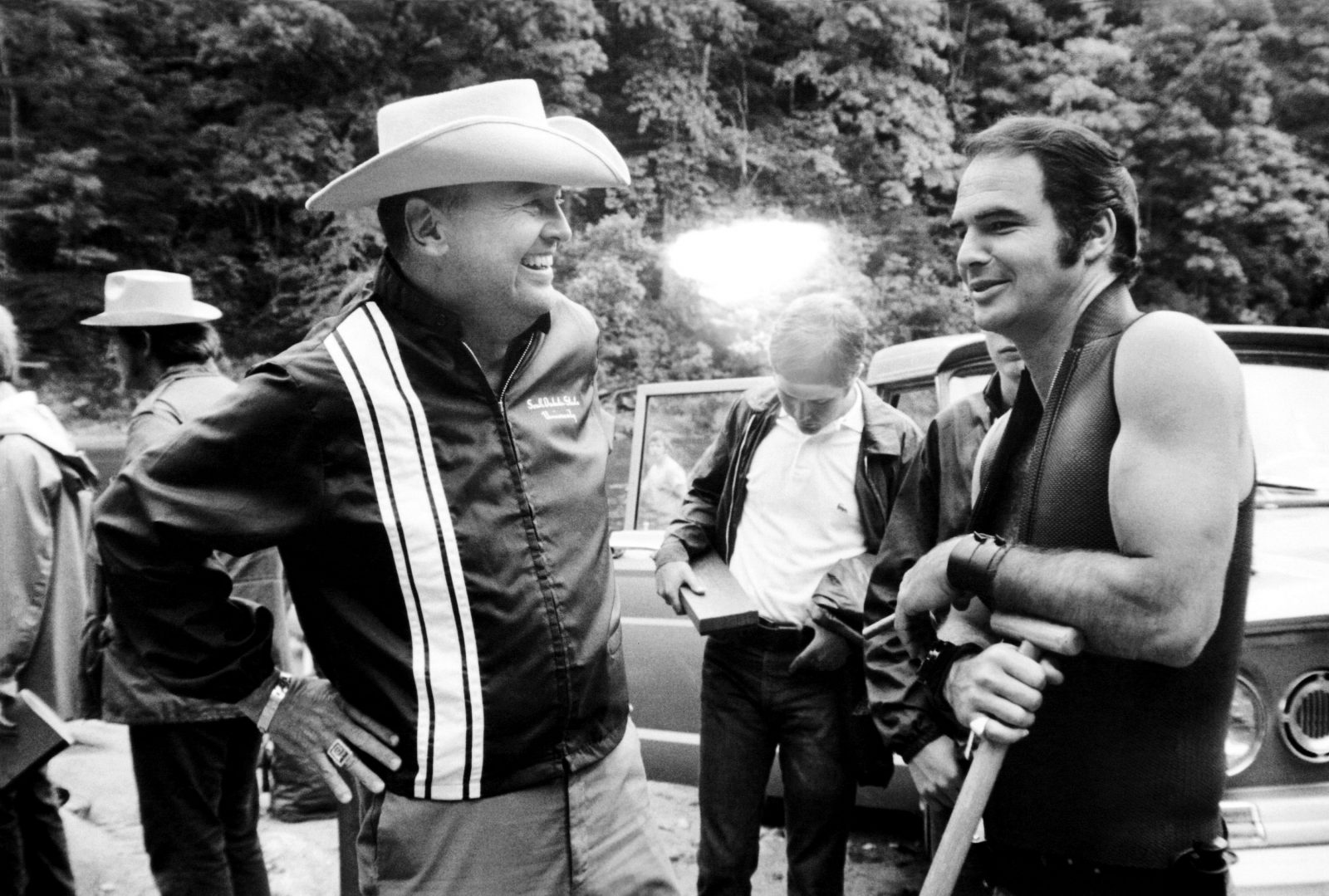

Photo: Rare Book Library, Emory University

Dickey, as the sheriff, on set in Georgia with Burt Reynolds in 1971.

BURT REYNOLDS: Dickey is fascinating—one of the most exciting men I’ve ever met. I had a terrific kind of respect [for] and fear of him.

JON VOIGHT (Ed Gentry): You tried to figure out who the hell you were dealing with. He had great confidence in his persona—more than I have. I’m a person who questions everything, myself most of all. Dickey didn’t have that gene.

RONNY COX: Jim was a type-A male who wanted everything. He really thought he was going to go down there to Clayton and direct the movie and do everything else.

After rehearsals, the cast would visit the country club’s bar/restaurant for drinks and meals.

BURT REYNOLDS: One night, I was sitting at the end of the bar and Dickey said, “Lewis!” And I didn’t answer him. So the bartender said, “I think he’s talking to you.” And I said, “He ain’t talking to me.” So Dickey said, “Lewis!” He wandered down and leaned over me, which was like a house leaning over you, and he said, “I’m talkin’ to you, Lewis.” I said, “You’re not talking to me, Mr. Dickey, because my name is Burt and ‘Lewis’ works tomorrow between seven and five.” And he said, “That’s exactly what Lewis would have said.”

RONNY COX: He never, ever called me Ronny. He always called me Drew. We were rehearsing, and he liked what I was doing. A couple of days later, we were coming back from canoe practice and Jim was in the bar, holding forth. I came in and he said, “Drew! Drew! Get over here. I want you to do that scene.” He actually wanted me to do a scene for a bunch of drunk guys. I didn’t do it.

JOHN BOORMAN: The actors got very upset.

Beatty arrived in Georgia just as Boorman decided that Dickey had to be dismissed.

NED BEATTY: I had no idea what had been going on. Dickey was getting kind of liquored up during the evening and going into this whole thing about his movie. He would talk about what it was going to be like and say, So-and-so is going to do this and Come over here, Drew, and tell these guys why you’re going to play this. Ronny was really having a problem with it.

JOHN BOORMAN: I said to Jim, “I think you should go and let us get on with rehearsals and you come back and play the sheriff.” He said, “If I’m goin’, you can get yourself another boy to play the sheriff.”

RONNY COX: He thought John Boorman was just trying to steal the film, sabotaging him.

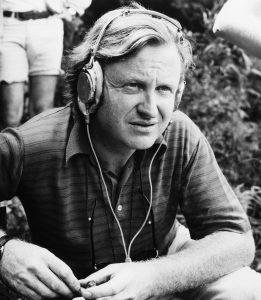

Photo: Courtesy Everett Collection

Producer and director John Boorman.

JON VOIGHT: We didn’t need someone looking over our shoulder. We didn’t need to be self-conscious about what we were doing, and that’s why Dickey had to leave.

Using their own self-styled “intervention,” Boorman and the four actors confronted Dickey together.

RONNY COX: During the course of that meeting, Jim played all four of our characters for us without knowing it. He played Lewis—“By God, this is my project. You can’t kick me out of here.” Then he was reasonable, like Ed. Then he was Bobby, the jokester. When he played my character, Drew, he was almost in tears.

NED BEATTY: How can you just say, You’re going to have to leave? I thought, You’ve got to be kidding—you can’t tell this man that. I felt like I had to protect Dickey in some way. When the time came for me to say what I had to say, I tried to be as grown up as I could and told him, “I really love your book and what you’ve done with the script, but what we do is such a totally different exercise that there’s just no way we can compromise. Rather than acting out something like you think, we do it together—we play off one another. You’re going to have to let us be free to do that.” I was way above my grade level in saying these things to him.

RONNY COX: When it came to me, I sort of wasn’t able to say anything. I was just sort of mute.

JOHN BOORMAN: Jim was a very imposing figure. He drew himself up in front of the four men and with his eyes blazing he said, “It appears that my presence would be most efficacious by its absence.” And he left. Burt said to me, “Does that mean he’s going or he’s staying?”

RONNY COX: We talked for a couple of minutes after he was gone, and then the four of us left. Jim was waiting for me outside. He said, “Drew, I’m really disappointed in you.” I said, “Why?” He said, “I know you wanted me to stay and needed me to stay and you didn’t have the guts to stand up and tell ’em that.” It was amazing. I finally figured out why he called me “Drew” and Burt “Lewis” and Ned “Bobby”: that meant he sort of owned those characters.

TOM PRIESTLEY (film editor): I had supper with Dickey that evening, and he was very taciturn. I remember saying to him, “For a man of words you’re amazingly silent.” It was only later I found out that he’d been invited to leave.

V. THAT SONG

Dickey departed, and Boorman and the cast and crew resumed with rehearsals and preproduction. Meanwhile, Stalmaster was still lining up locals for minor roles, including a banjo-playing boy called Lonnie whom the main characters encounter early on at a dilapidated gas station. A draft of the script described him as an albino, “probably a half-wit, likely from a family inbred to the point of imbecility.” It was to be a signature moment of the movie: Drew, a character from the city, and this boy from the hills play a song in which guitar and banjo “answer” each other. Boorman didn’t want an actor to play Lonnie.

LYNN STALMASTER: There was a man in Clayton called Tom Rix who showed me around. I said, “Somewhere I have to find a very odd-looking boy. Can you take me to a local school?” He said, “Let’s go down to the local grammar school.” The door had a window in it, and I looked in and scanned the students. Suddenly, this boy appeared. He looked exactly like the kind of youngster John Boorman wanted. I couldn’t believe it, and ran to the phone and said, “I’ve found a boy I want you to meet.” His name was Billy Redden.

DON RENO*** (bluegrass musician): I recorded [“Feudin’ Banjos” in] 1955 with Arthur Smith. We called it “Feudin’ Banjos” back then and they picked it up and put it in a movie and called it “Dueling Banjos.”

***The late Don Reno is quoted from his album Don Reno: Founding Father of the Bluegrass Banjo.

TOM PRIESTLEY: We got two musicians who came down from New York, and we thought of all the variants of that particular theme that they could play. Then I selected what I thought were the most appropriate bits and put them in.

RONNY COX: Steve Mandel, who played the guitar on the [sound track], taught it to me note for note. In the movie, I played the piece—every note. We were always going to match playback. Is that me on the sound track? No. Did that probably cost me about a million dollars? Yes.

TOM PRIESTLEY: There was very little music [overall]. Had Deliverance been produced in more modern times, let’s say as a Spielberg movie, it probably would have had pretty much wall-to-wall music.

RONNY COX: The other three characters have a real suspicion of the mountain people. But my character, Drew, made a connection with the kid playing “Dueling Banjos” and sort of realized they were all just like him. Remember the scene where Drew is in the canoe and the kid is on the bridge, looking down on him? You can see that Drew didn’t have the same fear. That’s my favorite shot.

VI. “YOU DON’T BEAT THIS RIVER”

TOM PRIESTLEY: Boorman was very keen on having a particular look for the film, and he found a technical way of doing it—marrying color film with black and white. So the river itself looked black. It had a strong, almost evil look to it.

RONNY COX: We shot in sequence. In the book and film, the easy rapids are in the beginning and they get harder as you go. There’s a guy out there who claims that he did stunt work on it. Bullshit. All that canoeing—that’s us.

TOM PRIESTLEY: A lot of the river stuff was in effect improvised because they were actually doing it. Let’s say the canoe going down a rapid might unexpectedly twist ’round or somebody’s hat would fall off—we incorporated that into the final cut.

About forty pages into the script are the scenes leading up to Bobby’s rape. The main perpetrator was played by Bill McKinney, who tested for the role of Lewis. Boorman liked McKinney but made him the rapist instead. (In the script, the character is identified as “Bearded Man.”) As it turned out, Reynolds was responsible for the casting of the toothless other attacker.

BURT REYNOLDS: I used to fall off a roof in a Western show at Ghost Town in the Sky, an amusement park in North Carolina. I got paid

seventy-five dollars a week. I remembered this guy—Herbert “Cowboy” Coward, a wonderful actor—he played Pa Clampett or somebody who did the gunfight. His two front teeth were missing and he stuttered. So I suggested him to the director and…he came to read. God love him, Cowboy couldn’t read, so I gave him the lines and he was a marvelous actor. In the reading of the script, the director said, “Do you realize what you have to do in this picture?”—explaining to him that he had to jump this guy’s bones. He looked at the director. “I’ve done a lot w-w-w-worse things than that.”

NED BEATTY: When I was still in high school outside Louisville, Kentucky, I went to work at this man’s farm because I wanted to date his daughter, actually. My first job was to round up all these hogs that had gone wild. At least fifteen of them were boars—and they had not been castrated. Because I was a football player, I was given the job of hitting the boar with all my strength up on the shoulders and knocking him down on the correct side, like I was doing a block. As fast as possible, I had to get some rope around his feet and nostrils so he wouldn’t bite me. This older man who was well into his sixties would grab the correct hind foot that we had to lay over. I had to sit on the boar’s head while they performed this awful operation on him. That really came back to me. I started telling the director and the other actors, and they understood.

JON VOIGHT: It’s a nightmare journey.

NED BEATTY: Most of the people that were on the movie did not want to do the scene. They wanted to skip past it. (Long pause.) We did it anyway.

BURT REYNOLDS: It’s a very heavy picture.

After Bobby’s ordeal, Lewis shoots the rapist with an arrow, killing him. After a heated argument, the four men decide to bury the rapist’s body and then head on down the river. While in the canoe, Drew collapses and falls into the river and drowns. The audience is left wondering: Was Drew shot by one of the mountain men?

RONNY COX: Boorman said to make it ambiguous. There’s no gunshot wound. I think it’s much more interesting philosophically—what if  Drew wasn’t shot? I think his whole moral fiber just sort of snapped and then he was out of it. His paddle hit a rock, he flipped out of the canoe, and hit his head on a rock.

Drew wasn’t shot? I think his whole moral fiber just sort of snapped and then he was out of it. His paddle hit a rock, he flipped out of the canoe, and hit his head on a rock.

NED BEATTY: Burt and I used to get in trouble because we were in the better canoe and were ahead, going downstream. I kind of loved it. I was the only one who had ever had a canoe paddle in his hands before. One day we ran into a shelf. I could see it coming. I told Burt, “Let’s back this thing up. Back it up, back it up!” I looked back and he was sound asleep, slouched over. And I thought, You prick. I saw what was coming and knew the shelf was going to be small falls. We wouldn’t have a chance to get out of there—we’d go under. So I just jumped in the water and took the oar with me. Burt really thought he’d done me in. He was just screaming, “Ned, Ned! Where

Photo: James Dickey Papers, Manuscript, Archives

Mountain Man

Herbert “Cowboy” Coward, who played one of the two attackers, gets fitted for an arrow.

are you? Jesus Christ! Son of a bitch! Ned?!” I’m enjoying this, just underneath the water, and I let it go on as long as I could. I finally came up

and said, “I’m fine, how are you?”

Following Drew’s death, it came time for the scene when Ed makes a nighttime climb up the face of a mountain to kill the man who the others believe shot Drew.

JON VOIGHT: I was so in love with what Dickey had done with that chapter, and wanted to accomplish it visually. It was a masterpiece of writing, which only could have been accomplished by a poet. I look out and there’s a moon reflected on the waterfall and I’m up there with a bow and arrow—this guy who is a salesman, pausing in the midst of this frightening adventure to take in the beauty of the nature around him. I look out and say, “Christ, what a view.” When I was deciding to do the movie, I could see my face saying that. I said to myself, I don’t know another actor who could get that moment the way I think I can. In a case like this where something was so sublime, you feel like you may have come up short, that you didn’t quite do it justice.

Ed kills the mountain man, and the three suburbanites, ridden with guilt and fear, continue downriver, where they soon meet the investigating sheriff, played memorably by Dickey. “Now, what about this?” Dickey’s delivery of that line was pitch-perfect, in “tones of true backwoods menace,” as the author Geoffrey Norman wrote in Playboy.

NED BEATTY: I was pleased as plump that he came back.

RONNY COX: He was over getting kicked off the set. He was very cordial to everybody.

JON VOIGHT: Dickey wrote a long speech for himself to give as the sheriff. And Boorman was such a clever man and brilliant filmmaker he told him, “When you start this speech, you have to come to the front of the hood of the car and say that paragraph. Then come over to the window and talk to the character of Ed directly.” So Dickey did it. And then of course what happened was that John simply took out the section where Dickey was standing in front of the hood. He got Dickey’s speech down to a workable size. But Dickey was an actor—he acted in his daily life. He put drama into everything. That’s what I figured out.

TOM PRIESTLEY: Dickey’s character has this line in the final scenes—“I’d kinda like this place to die peaceful”—which I think is the best in the whole film. It says so much. He knows there’s some strange business going on—let’s not stir it up.

VII. ON THE BIG SCREEN

JOHN BOORMAN: I did a rough cut and took it to Warner Bros. and showed it to them. The response was one that I got used to, which is that people just walked out without saying a word. People were sort of devastated by it.

At a premiere in Atlanta, Dickey’s tennis mate Al Braselton sat next to Jimmy Carter, then governor of Georgia. According to Braselton, when the lights came up, he turned to Carter and said, “This ain’t no Junior League movie, is it, Governor?” Carter replied, “It’s pretty rough. But it’s good for Georgia…I hope.” Deliverance opened nationwide on July 30, 1972. Moviegoers and critics alike were astonished by its authenticity, thanks in part to the performances delivered by the locals.

RONNY COX: The hardest thing in the world is to get non-actors to give performances that aren’t self-conscious. But look at Ed Ramey playing the old man at the service station, or the people around the dinner table.

JOHN LOGUE: My wife and I went to see Deliverance, and there were a bunch of college kids sitting right in front of us. Before the movie started, they were giggling and laughing. I don’t know what they were expecting, but in a short while, you never heard such silence.

PAT CONROY: I went to see it in the Atlanta suburbs with a couple of kids from my class. It was an early movie and there weren’t that many people there. When Jim came on the screen as the sheriff, somebody in the back of the theater jumped up and began applauding. It was Jim. Applauding himself. He was clapping and yelling, “Nice job!” I thought, That’s how a poet acts.

T. C. BOYLE: It was one of the few examples of a great book making a great film.

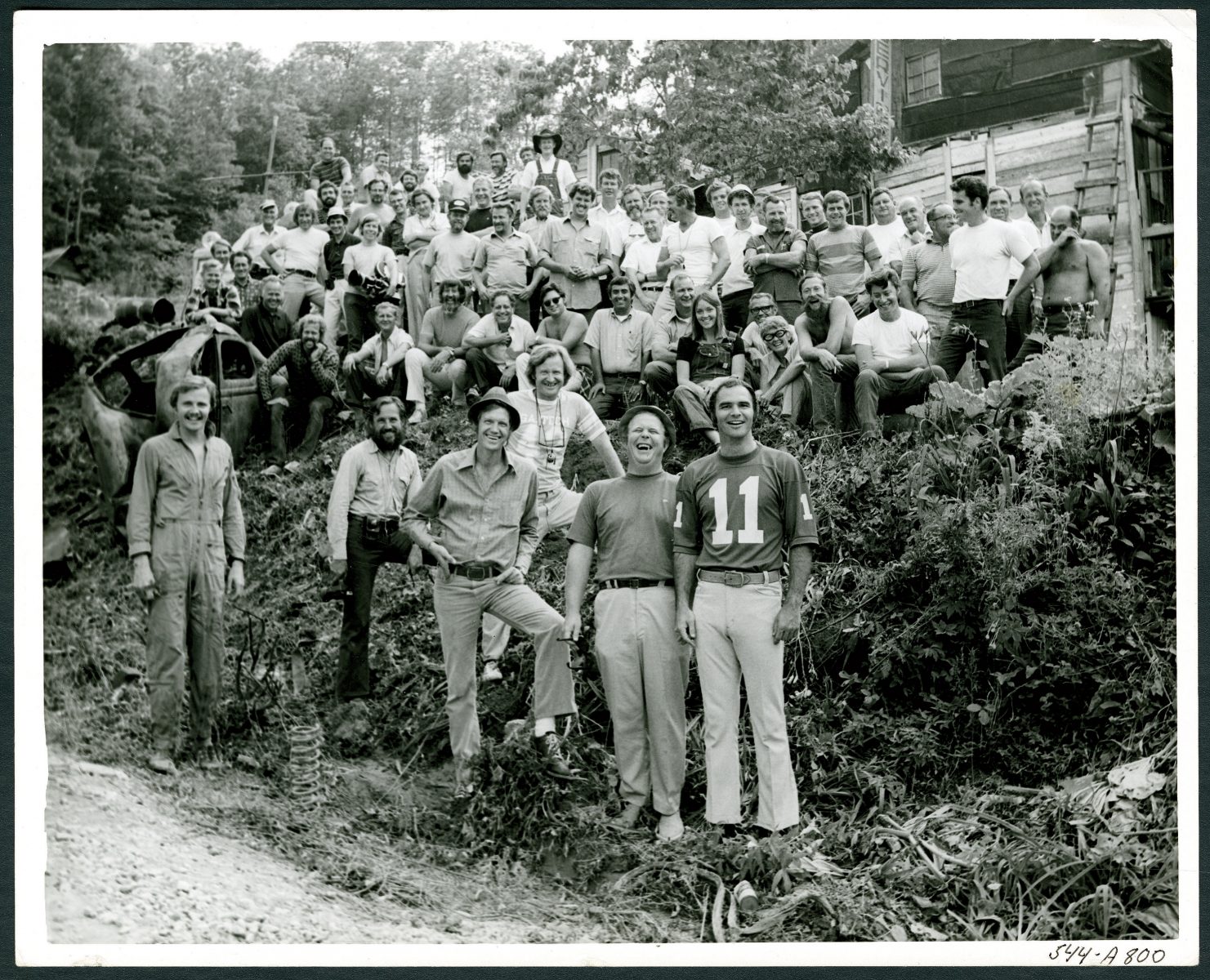

Photo: James Dickey Papers, Manuscript, Archives

Good Company

The cast and crew pose for a group shot during filming near Clayton, Georgia.

GORDON VAN NESS: Jim’s father walked out of the theater. He felt the movie was an affront to Southerners. Jim said, “Dad never saw the scene where they’re sitting around the table eating dinner and the bounty of food that’s being given by these people who don’t know the four canoeists—the good things about the South and its people.”

RONNY COX: A lot of people think we vilified the hillbillies. If you found two rapists in Montana or Hawaii, you wouldn’t be saying that everyone there was bad. If you look at all the other people, they’re sweet, nice, kindhearted people. Deliverance is about America. I think Jim Dickey really thought it was this whole sort of libertarian thing—that the ones who are prepared are the guys that are going to succeed.

DAVID GILER: Boorman never really understood the book. It’s about the deliverance from one kind of life to another.

GORDON VAN NESS: If you want an adventure, go watch the movie. If you want something that deals more with the mythic hero and the relationship between civilization and nature, then go read the novel.

Deliverance received three Oscar nominations, for Best Picture, Director, and Film Editing. Success continued for Dickey with his 1974 book, Jericho: The South Beheld, published by Logue. It became a mainstay on coffee tables throughout the South.

JOHN LOGUE: Dickey and I were in Atlanta at Rich’s Department Store out at Lenox Square. Two thousand people lined up to buy Jericho. Dickey was signing and then he took a little relief. He said, “Logue, we done sat down in the cream jug.”

CHRISTOPHER DICKEY: With fame came a particular kind of indulgence. People want poets to be bigger than life, to be outrageous, memorable, excessive. They will give them more than enough to drink. They will sleep with them. They will tell stories about them. And all that is seductive for both the poet and his audience. What Deliverance did was take that to a whole new level that was destructive for my father.

PAT CONROY: I don’t think there was enough fame for Jim to get out of life. He had an enormous appetite for it. If he could have had it all, he would have taken it all. In his last years as a poet, I think he could see himself losing it—not quite getting the same attention with his novel Alnilam as he got with Deliverance. He struggled to get back to that, always.

James Dickey died at age seventy-three in 1997, but 2013 saw the publication of The Complete Poems of James Dickey, a 920-page collection, and a volume he was working on when he passed, Death, and the Day’s Light, came out last spring. Deliverance lives on: The novel is still in print, and last fall a new stage version of the book debuted in New York. One wonders how Dickey would have regarded Deliverance’s new life as a play.

CHRISTOPHER DICKEY: He’d take possession of it. He’d say it was the best damned play ever produced on or off Broadway. He’d stand in the lines outside the theater and ask people what they thought of it and then say, “That’s my play!” That’s what he did when the film of Deliverance came out. But there’d be this difference. He had mixed feelings about the movie. I think he’d absolutely love the play because, in the end, it is about language. And so is he.