Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from the G&G book S Is for Southern: A Guide to the South, from Absinthe to Zydeco. A compendium of Southern life and culture, the book contains nearly five hundred entries spanning every letter of the alphabet.

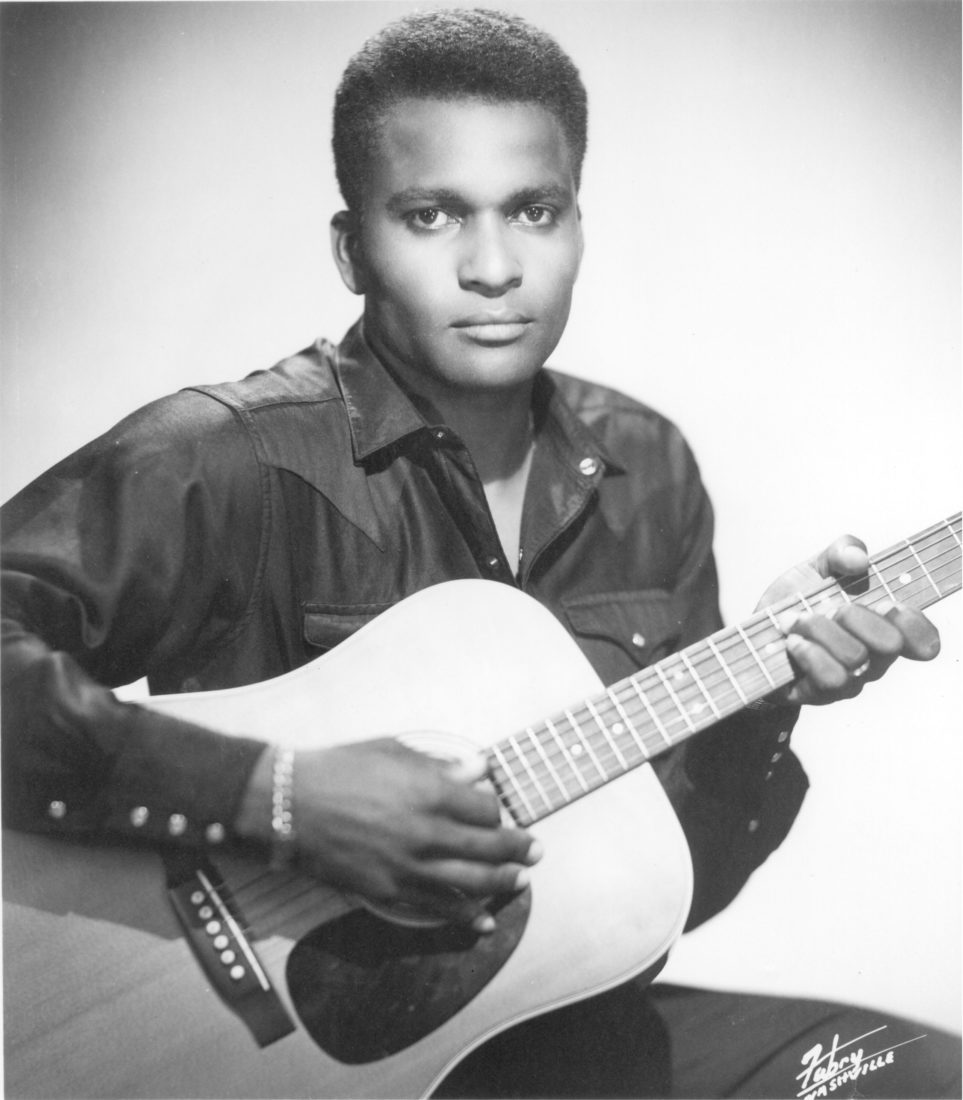

In some alternate universe, there’s a bust of Charley Pride in the Baseball Hall of Fame. This is not as far-fetched as it may sound. Though many know the best-selling, Grammy-winning recording artist as the only African American country music star of the late sixties and seventies—with record sales that rivaled Elvis’s—he also played for years on Negro American League and minor-league teams, pitching for such squads as the Memphis Red Sox, the Birmingham Black Barons, the El Paso Kings, and a semi-pro Montana team called the East Helena Smelterites. A native Mississippian and son of a cotton sharecropper, Pride began singing publicly while living—and actually working at a smelting company—in Helena, initially getting paid ten dollars to sing for fifteen-minute sets at games. In Montana he sang solo, made demo tapes, and joined a four-piece combo called the Night Hawks.

I remember, as a country boy growing up in the 1970s, how ubiquitous Pride’s hits were on the radio: “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’,” “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” “I’m Just Me.” He was a mainstay on Hee Haw and The Lawrence Welk Show, and on Bob Hope specials. Black folk certainly knew who he was, and respected him after a fashion, though I’m not sure he drew their affection the same as James Brown, or Al Green, or Diana Ross. There was something Nixonian about his success, something peculiar, irregular. Southern white folk seemed to accept him in a color-blind way, though jokes I heard from my white grade-school classmates made it clear they could see the man singing on their TV screen. In truth, Ray Charles had previously broken down walls between what was then known as country and western and other genres—rhythm and blues, soul. Charles’s 1962 album Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music and its follow-up made a strong case that those forms all sprang from the same American roots.

Pride’s career break came in 1966, when the legendary Chet Atkins took an interest in his song “The Snakes Crawl at Night” and signed him to RCA Victor. Pride was not an instant hit. Although he played the Grand Ole Opry as a guest in 1967—the first Black player there since a harmonica player in the 1940s—the Opry and its audience were not a progressive lot at the time, and he didn’t become a member until twenty-six years later. But radio soon turned out to be very, very good to him. Between 1967 and 1987, he scored fifty-two Top 10 hits on Billboard’s country charts, won two Grammy awards for gospel, and in the early seventies was named the CMA’s best male performer twice. All in an era when the face of country was overwhelmingly white.

Comparisons to Jackie Robinson are too easy; some club owners refused to book Pride at first, and he was denied some opportunities readily available to other country performers. He forged on, not exactly silent about the slights, but not making much of a fuss either. “No one had ever told me that whites were supposed to sing one kind of music and Blacks another,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I sang what I liked in the only voice I had.”

By now, still performing in his eighties, and part owner of the Texas Rangers, Pride has become an old-school country grandee, inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000. After him would come Darius Rucker, Mickey Guyton, Linda Martell, the Pointer Sisters, Rhonda Towns, Rissi Palmer, Valerie June. All underscoring a lasting and powerful Black presence in country. But Charley Pride was the pioneer—the country airwaves’ first dark balladeer.

S Is for Southern is available at Amazon, Fieldshop, Bookshop, and in bookstores everywhere.