Q: Does anybody write thank-you notes anymore?

If by that you mean you don’t, dust off those robin’s-egg-blue boxes of engraved cards and get back on the stick, dammit. If you’re asking in the parlous state in which many of us find ourselves—namely, facing barge loads of digital muck we can barely shovel through, so that we flag when confronted with yet another thing to write—then let’s take a stroll through the battlefield of recent epistolary action. Three points: Although an email might be considered a sufficient “modern” thank-you manqué in Cupertino, California, this is the South—our shirts have collars, our dogs do not own domain names, and we write thank-you notes. Second: An email has no context. It brings this greasy freightlessness into the business environment, and that can be helpful. But emails are actually less personal than a phone call, which is anathema as an expression of gratitude. Finally, the discipline of composition: Take the pen in hand and do that age-old thing we have been doing since we invented cuneiform. Before you put the implement to the surface, think about the person whom you are addressing. That’s your reward.

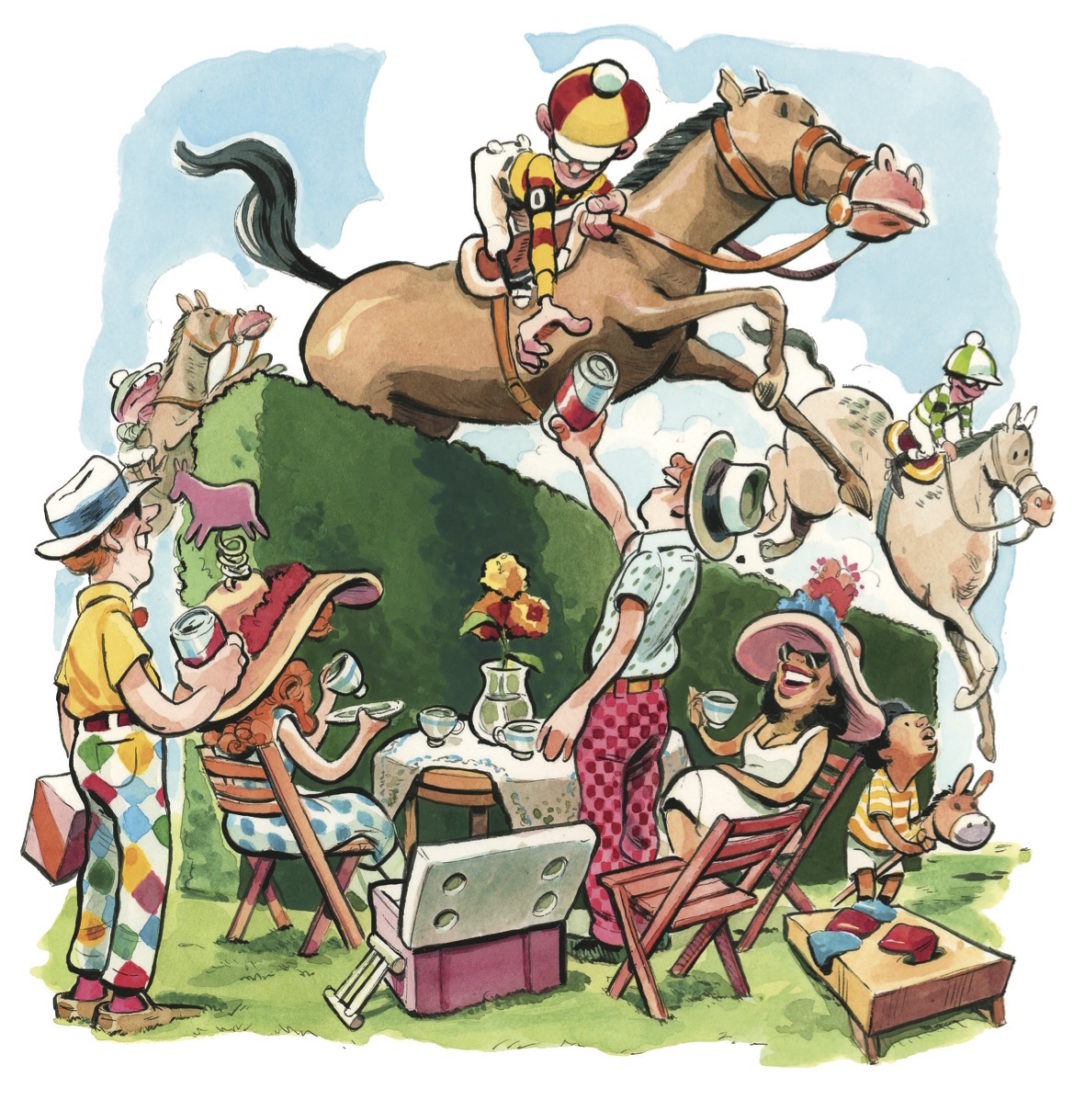

Q: We heard the Tryon Block House steeplechase is a tradition worth pursuing. Go for it?

You’ll have a helluva lot of good country fun with some fine horses if you do. Staged this year on April 11 in Columbus, North Carolina—as ever, by the Tryon Riding & Hunt Club—this ’chase-season rite of spring will provide you with two parts: the racing and the tailgating. Club members take the latter seriously—in addition to hat contests, there is the Best Fancy Party judging, but unless you are bringing Grandma Vashti’s silver tea service, a couple of candelabras, and some good linen, I wouldn’t bother competing. This year’s meeting marks the seventy-third running, for which we have to thank Carter Pennell Brown, a Midwestern hotelier and horseman who moved to Tryon and in 1925 founded the club. In 1947, he created the first race around the old Block House, an eighteenth-century log redoubt in the French and Indian War that went on to do service as a trading post, a tavern, an inn, and of course a whorehouse before falling into disrepair. The event has moved a few miles down the road to a sanctioned course, but without Brown’s delightful obsession with jumping horses competing cross-country, there would be no Block House. The festivities also include a manly ugly pants competition—a contest I’ve never won, though I aspire to—so do channel your inner John Daly. As in, go well beyond that pair of lime-green golf slacks with the little orange ducks you’ve been ridiculed for at the country club. This is the ’chase. You gotta go uglier.

Q: Remind us what makes Satchel Paige such an icon?

The first African American pitcher to move from the Negro leagues to the American League, and the first African American pitcher to pitch in the World Series, Leroy “Satchel” Paige was born in 1906 to John and Lula Paige in the humble district of Mobile then called Down the Bay. Paige was gifted with three elements of genius: an immense physical talent, a superior tactical intellect, and the inner fire to change his sport’s political condition at the national level. As an athletically precocious black male in South Alabama in 1918, he would inevitably be arrested, nominally for throwing rocks, whereupon the Alabama judiciary railroaded him with a sentence to “the Mount,” the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Lawbreakers in Mount Meigs. Paige was all of twelve. Mount trustee Reverend Moses Davis taught him how to pitch. By the 1930s, he was a national sensation, his games with the Crawford Colored Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs drawing unheard-of crowds, including a record 51,723 fans when he pitched the 1943 East-West All-Star Game. One of his showboat flourishes was to order his outfield to sit down, after which he would strike out the side. Major leaguers queued to play Paige. Joe DiMaggio called him “the best I’ve ever faced, and the fastest.” After Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Cleveland Indians hired Paige, and the team promptly won the 1948 World Series. Paige’s shoulders were broad, and served not simply as the excellent fulcrum for his blazing arm speed. With them, he threw major-league baseball, and America itself, into new, egalitarian territory.

Have a burning question? Email [email protected]