Good-to-be strays thrown out in the middle of the country by impatient and/or unready dog owners invariably crawl on their bellies, eyes up and pleading. I’ve never lived with loving and judicious ex-strays that didn’t appear in my yard, then come to me as if mimicking a Parris Island soldier-in-training forced to crawl beneath razor wire. River showed up thusly, as did Gypsy, Lily, and Sally. All my other ex-strays over the years—Nick, Maggie, Stella, Marty, et al—have been great dogs in their own ways, but they’ve never fully shaken the feral out of their coats.

My dog Dooley appeared on March 1, 2000. I went out to the front yard at dawn with my then-nine-year-old dog, River. Fog hung low. I could see my neighbor’s visiting mother-in-law a hundred yards away, a new dog beside her. I yelled out, “Hey, Dot, did Jim get a dog?”

With this, Dooley came running toward River and me. River—one of those mixed breeds that look like coyotes—didn’t growl, bark, or wag her tail. Dot yelled back, “No. That’s not our dog.”

Dooley—white and liver-spotted, mostly legs, thin as a whisper—dropped onto his belly, eyes up, with what looked like a smile. He crawled past a Leyland cypress, a fig tree that appears to be a bonsai, and a crab-apple tree. He reached River. They touched noses. I won’t lie here: At the time Glenda and I had eight ex-stray dogs and Herb the ex-stray cat controlling us, all of which emerged from the tree farm across the road, and I thought, I need to take this boy down to the Humane Society.

Dooley followed River and me inside. I put a bowl of dry food down for him and said to Glenda, “See if anyone wants a dog over at the school,” et cetera. On this particular day I had to drive down to a detention center for juvenile delinquents in Alabama to teach them some fiction writing, oddly. I needed to get on the road, and wouldn’t return for three days. “We can’t afford another dog,” I said. I meant it, too.

I came back from my little trip. Dooley sat in the laundry room, chewing on the molding. “No one wants a dog,” Glenda said. “He’s a great dog. He’s tried to eat through the wall and the half-door, but he’s house-trained.”

To this day—some twelve years later—I have no clue how hard Glenda tried to find the dog another home.

Here’s Dooley between March 2000 and Labor Day weekend 2010: Whenever I pick up car keys, he runs to the door. When there’s a bird, squirrel, or rabbit somewhere outside, he’s staring out the window. If I yell out “cow,” “horse,” or “Republican,” he’ll run to a window and bark. When I go off on book tours, Glenda says, he won’t eat, and barely leaves my writing room. He lived with me at Wrightsville Beach for five weeks and stared at seabirds nonstop. He’s curled up below me now as I write this. River died at the age of fourteen, and since then Dooley’s been the official greeter and tester-outer of two more strays that showed up. He’s our largest dog, but the gentlest. He’s that dog.

A week before Labor Day in 2010, I had to put our dog Marty—nineteen years old—down. I buried him in the backyard next to Ann, Hershey, River, Inklet, Nutmeg, Joan, and a stray we’d been trying to coax over for a month that some overzealous DNR agent shot in the tree farm. Nineteen! One time when I wasn’t paying attention, Marty—part bulldog, mostly underbite—had stuck his head in my plastic cup and drank about sixteen ounces of a bourbon and Coke. He wobbled around, peed on himself, and then wouldn’t come near booze for the rest of his life. I buried him deep, and placed some chicken wire and a cement block on the grave.

Seven days later I ventured way in the back to ride a stationary bike that I keep out of sight so that I don’t ride it too often, and I said, “What smells? Something’s dead out here.”

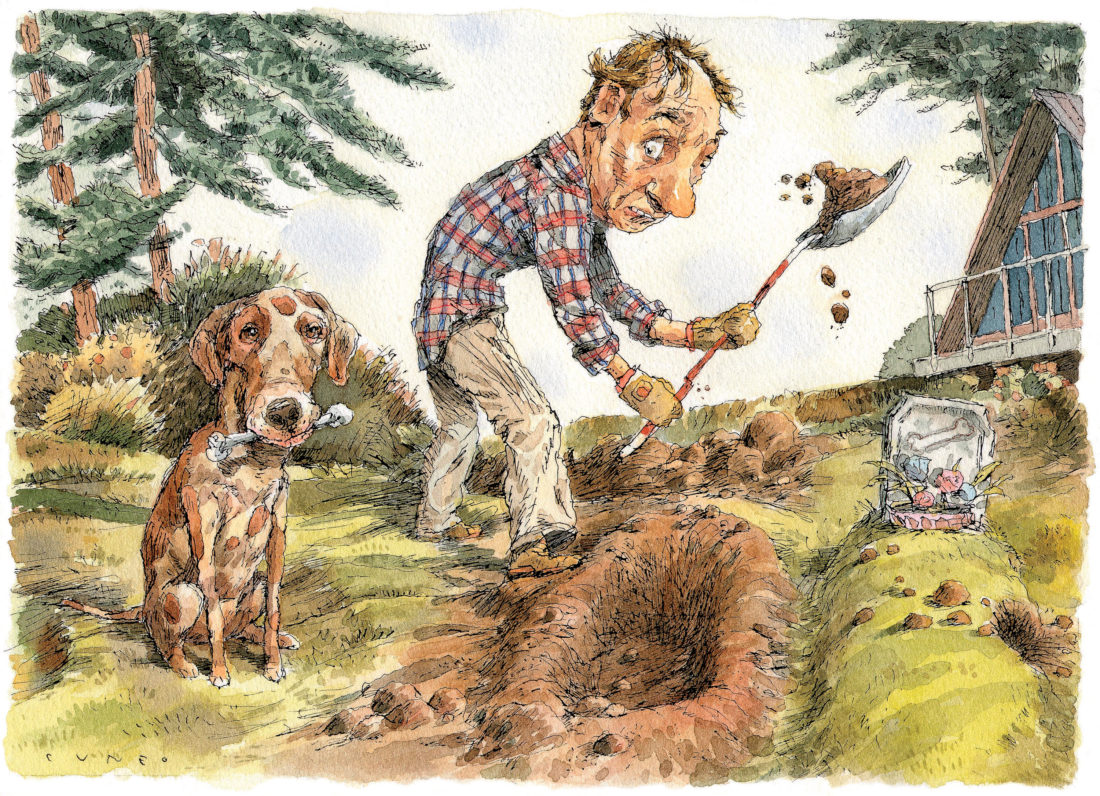

I got off the bike and found—oh, no—Marty’s back leg pushed out of his grave. It seems as though Lily and Sally—two feisty new ex-strays—had tunneled in from the side. I shaded my eyes, for some reason, and pushed Marty back in. I dug a hole and threw that hard clay over the grave, tamped it down, put the chicken wire back down, placed some tin roofing over about a four-by-eight-foot area, found some hurricane fencing to cover the tin, and then covered the area with eight cement blocks. There are smaller grave sites for world leaders than the one Marty now has.

That night, at about ten o’clock, Dooley threw up a bowl of undigested food. I said, “Damn, Dooley, what’s wrong?” I cleaned up the mess.

He drank a half-bowl of water and vomited.

I cleaned that up and took him into Glenda’s studio instead of my writing room.

He drank water, he couldn’t keep it down—this went on until dawn. Even though I had done well in a college logic course, I didn’t make a connection between some things. I thought that Dooley had an intestinal obstruction—one time years earlier our dog Ann ingested a number of unripe peaches that fell off the tree, skinnied up, and the veterinarian ended up giving her a simple enema that cost us $250 to get thirty peach pits out of her system.

I took Dooley outside and gave him the same treatment—I’ll jump ahead and say that he wouldn’t look me in the face for a good few days after this—but to no avail.

I drove him into Greenville to the emergency vet clinic. This was a Sunday. Evidently it was Hit a Dog in Greenville Day, too, for Dooley and I sat there for a good three hours before a vet could see him. At this point—he didn’t seem dehydrated yet, he wasn’t throwing up—he seemed fine.

I took him home, he drank water and released it accordingly.

Twenty-four hours later, he could barely stand. I picked him up and got him back to the emergency clinic, where a great veterinarian named Dr. B. J. Rogers—whom I’d dealt with in the past when Stella needed an emergency hysterectomy—said, “He’s too dehydrated to do exploratory surgery. The X-ray shows nothing, but I know there’s something in there. We can do a sonogram later.”

That look on her face let me know that he might not make it. She left the room. Glenda touched my shoulder. I cried, cried, cried.

When Dr. Rogers came back in, I said, “Whatever it takes,” but my voice came out all squeaky.

She said, “Go on home. We’ll try to get him strong enough.”

Back home, I walked back to the graveyard to make sure the dogs hadn’t befouled my Marty grave. On the way I kept finding torn pieces of towel—the towel we’d wrapped Marty in before burying him.

I called up Dr. Rogers and said, “You’re going to find pieces of towel in his intestines. He evidently ate a towel.” I didn’t go into detail. I wouldn’t want the veterinarian thinking that we were some kind of low rent, towel-wrapping, dog-burying people in Dacusville.

She said, “Yep. We found it in the sonogram.”

Dooley survived the surgery, barely. He stayed at the clinic for a couple days, but they didn’t want to release him because he’d not peed. I showed up—he looked terrible—and said, “Let me just take him home.” When I got him outside on a leash, he peed for ten minutes on the grass—it seemed as though he knew not to pee inside, on a concrete floor. In my mind Dooley can do no wrong. Outside of saying to Lily and Sally, “Hey, give me that towel. If y’all eat it, you might get sick.” What a martyr!

My friend Ron Rash called me up a couple weeks after this incident. He said, “What’s been going on?” I started to tell him the entire story. When I got to “towel,” he said, “Are you making fun of me?”

“What?”

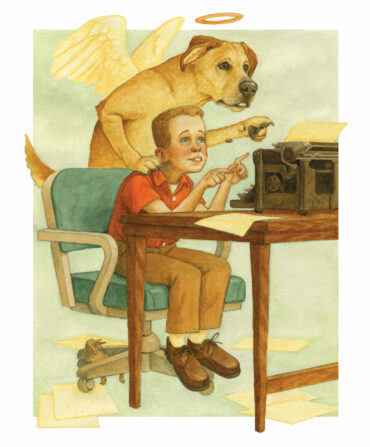

And then he told me about how his own dog, Ahab, had pulled a pair of Ron’s boxer shorts out of the dirty clothes, eaten them, and then undergone the same surgery as Dooley, by the same veterinarian. What’s going on with these South Carolina dogs that live with writers? I wondered. Is there something to reincarnation? Were they critics in a previous life? I like to think that’s the case—that Dooley once roamed this earth as a critic or editor, and that he’s at my feet now sending me high-frequency advice that only I can discern. “Write about me, write about me, write about me,” he’s probably communicating now. “Tell everyone about my fearless exploits.”