My daddy was a serious dogman. When he got out of the army after the First World War, he bought some surplus German shepherds, trained them to obey commands in English, and resold them. Business was good into the 1920s, when the enormous fame of one of the world’s first dog movie stars, Rin Tin Tin, vaulted the breed to the most popular in America.

In the thirties, he got the bird-dog bug, buying, training, hunting with, selling, and competing in field trials with dozens of English pointers and setters. Among the few tangible items he left behind when he died at ninety was a box of pedigrees, prize ribbons, and sepia photos of dogs on point in the field. His two all-time favorites were a patrician pointer, Jake, and a common little setter, Kate. Jake was really Ichabai Jacob, descended from the national champion Seaview Rex (and purchased from the Coca-Cola magnate Robert Woodruff), while he bought Kate out of a box on the front porch of a crossroads country store in South Georgia. (Entirely coincidentally, I like to believe, my oldest son is named Jake, and my wife is Kate.)

My mother was more ambivalent about dogs. While my daddy had as many as thirty-five dogs at a time in a pen out behind the house, or in a field he rented right where today I-85 crosses Piedmont Road in Atlanta, Mama had a little fox terrier named Toy, who lived in the house, rode in the car with us (as opposed to the trunk, which had holes punched in it for ventilation, or a trailer), and was her steadfast companion. He ate canned Ken-L Ration, like they advertised on TV; the other guys ate some combination of Purina Dog Chow and fifty-five-gallon oil drums of steak scraps that my father would pick up on Saturday nights at the back door of Twelve Oaks Steak House, there on the corner of Cheshire Bridge and Piedmont.

My earliest encounter with death came when creaky old Toy hobbled up from the mailbox with my mother and me and collapsed at her feet. She burst into tears and was inconsolable for days.

Then came Sammy. A jet-black cocker spaniel, he arrived one Christmas Eve when my grown sister showed up for dinner and presented him, without warning and sporting a red bow, to my teenage sister. I realize now that my mother was gritting her teeth, biting her tongue, and cursing the darkness at this unexpected holiday windfall. One clue should’ve been that, unlike Toy, he was banished to a doghouse she commanded my father to build in the backyard.

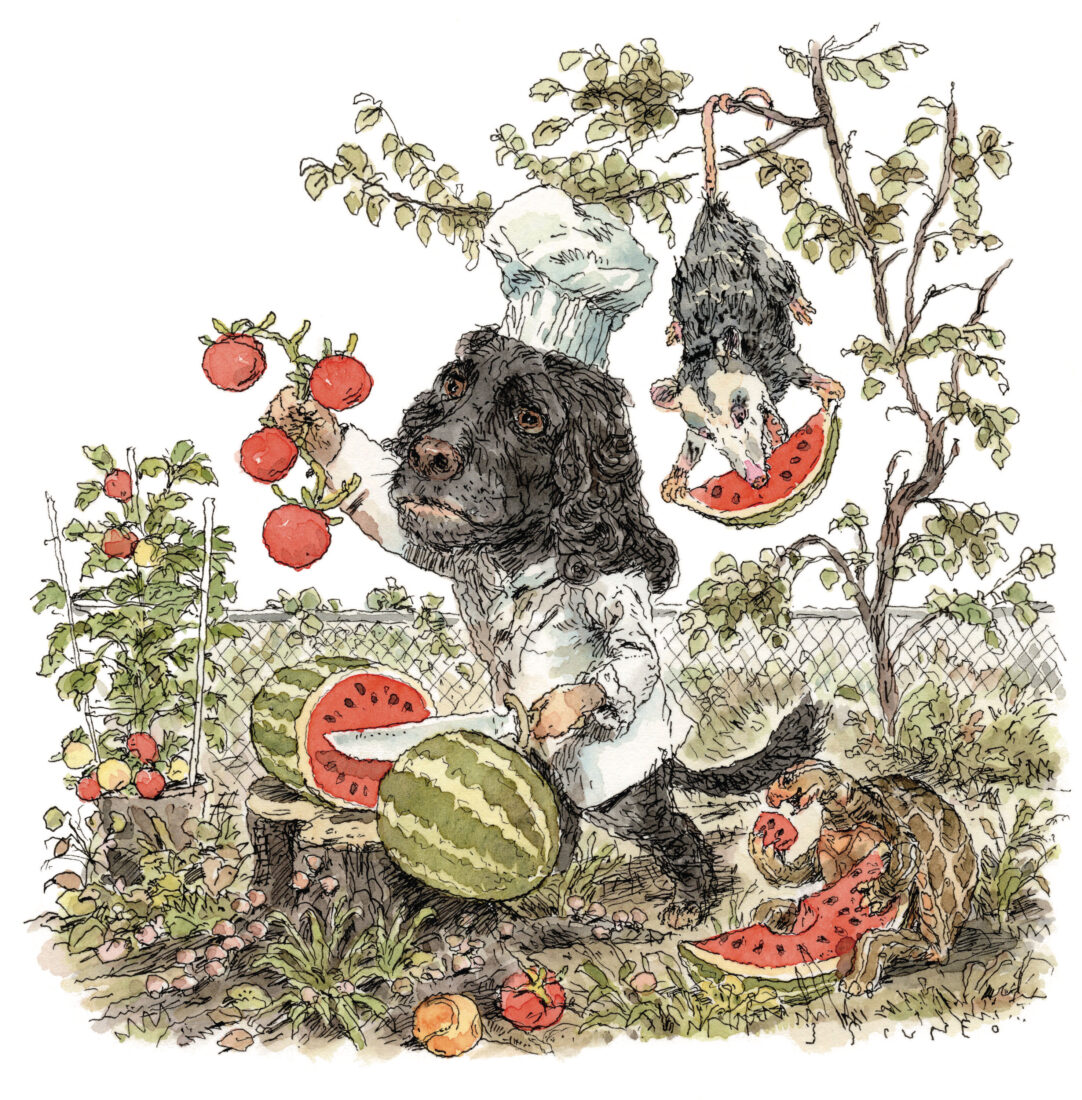

To my nine-year-old self, Sammy wasn’t just a good dog. He was the perfect dog. Here are just some of the things he excelled at being: A watchdog. (He barked at everything, including falling leaves.) A hunter-gatherer. (He regularly brought home box turtles, possums, and dead squirrels.) A retriever. (He could find an errant baseball no matter how thick the kudzu or brush pile. Getting it back from him was another matter.) An escape artist. (No pen or fence could hold him.) A dog of mystery. (Twice he came home from his wanderings covered in paint, once blue, once red.) A gourmet. (He loved tomatoes and watermelon off the vine.)

One day Sammy didn’t come home. Days passed, then weeks. Eventually, we put his things away and settled into a dogless life. Months later, the phone rang, and I answered. It was the lady who ran the beauty parlor at Regenstein’s Department Store in Buckhead, calling to say that an emaciated, flea-covered cocker had plopped down in the salon with a collar bearing our number. He had gulped down a bowl of water and was just lying there.

To my astonishment, my mother leaped into the car and rushed to Regenstein’s, just a few blocks away. He had no pads left on his paws and milky eyes, and he could barely stand. She whisked him to the vet’s office and pleaded with them to save him. Within days, he was gaining weight and moving around, and he had been promoted. His extended trip, wherever it took him, had gotten him where he wanted to be all along. He was now living in the house.

Sammy never ran away again, and he and my mother were inseparable from then until his death.

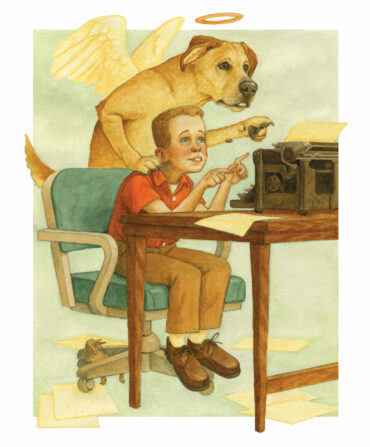

I was a freshman at UGA when the guy who ran the dorm came to my room at Milledge Hall one night to tell me my mother was on the phone and needed to speak with me. In the days before cell phones and phones in your dorm room and email and social media, you didn’t hear from your folks when you went to college. They heard from you when you needed something ($$$), but a call from home conjured the Angel of Death.

Sure enough, my mother was choking back tears when she spoke. “I wanted you to know that Sammy was eaten up with cancer and in a lot of pain and I had to put him down today. I know he was supposed to be your sister’s, but he was really yours.” I’m pretty sure I at least teared up at the news, but I was in college and had a lot of other things on my mind.

Besides, I think dogs are the ones who decide whose dog they are. From that Christmas Eve Sammy arrived, my mother hated him. She called him a devil dog. She gave him away once, but he was quickly returned. Something about being unmanageable.

Maybe so, but he was persistent. In the end, Sammy was my mother’s dog, and everybody except my mother knew it.

My father, meanwhile, after a lifetime of canine companionship, somehow switched over in his old age to a cat. A stray cat, at that. No one saw this coming. We were not cat people.

But one day my father showed up with a stray cat he had run across, gave it some ridiculously clichéd name like Fluffy or Whiskers or something, served it a bowl of milk, and spent the rest of his life with it sitting on his lap watching reruns of Gunsmoke, Perry Mason, and Bonanza.

I have stayed on the straight and narrow, owning a variety of colorful, miscreant, useless but charming dogs. We had one, for example, who ran off with her son in a thunderstorm. The son came home that night and later assumed a prominent position in the family Good Dog Hall of Fame. The mother, we learned months later, had strayed all the way from Garden Hills to an Indigo Girls concert at Chastain Park, where she was adopted by her new owners. When my wife learned this, we put the question of whether to repatriate the prodigal dog up to an anonymous family vote. The dog lost, unanimously. I imagine her expiring peacefully on a pillow in front of a crackling fire, listening to “Galileo.”

As I age out, I’m fairly confident I’ll finish up in the company of dogs. My wife and sons are all dedicated dog people, and as I type this, a dog named Gumbo is lying on my feet. At least I think he’s a dog. Something called a Mini Bernedoodle, one of those designer dogs. Everything except being a pet has been bred out of him. I call him Pixar because his markings are so perfectly cute he appears to have been animated.

Despite my condescension, it wouldn’t bother me if over time he drifted away from my wife and became, secretly, my dog. Sure, it would be a little embarrassing around all my friends who have Labs and Boykins and springers and some kind of French bird dogs whose names I can never remember. But it would be so much better than ending up with a cat.