The first night I brought Ernie home, he curled up on the pillow next to mine, defying physics with his compact roundness: from dog to perfect doughnut. I’d purchased a large training crate, as his foster mom had suggested, but couldn’t resist his sleeping face—made somehow sweeter by caramel-colored patches, shaped a bit like macaroni noodles, arching over his closed eyelids. He slept peacefully beside me well into morning.

Ernie had been listed on the shelter website as a fully grown adult pit bull mix (and with a shelter name, I’ll add, not nearly as apt or as adorable). In the website photo, both his brown fur and his snout, elongated by the camera lens, had reminded me of my sister’s dog, Jeffrey, whom I’d cared for in the last years of his life. Jeffrey was calm, loyal, and lumbering; friends and family referred to him as “the gentleman.” I was still mourning his absence and hoped my next dog would be just like him. That first night with Ernie, I marveled at my luck and good instinct; I’d known he was for me the moment I saw that eyebrowed face.

The next night, as I prepared to go to sleep, I called Ernie to join me again—but this time, he stood beside the bed and stared at me with a crazed look, wagging his tail but also growling before erupting into frenetic motion. He bounded with turbocharged force from room to room. Pillows flew from the furniture; framed art went sideways on the walls. He paused his rampage only to chase his tail in high-speed circles before racing off again. Frustrated and bewildered, I eventually led him over to his crate—his new bedtime routine, I resolved.

Within those first few days, his foster mom sent a check-in email. Previously, she had stressed that Ernie was a “great dog,” and that she couldn’t understand why no one had yet adopted him. Now that I had formally done so, she offered a lengthy description of Ernie’s myriad challenges, many of which I was already discovering.

She confirmed, for starters, what I had begun to suspect: He was still a puppy. He also dug holes in yards and gardens; he was a “door bolter” who raced full speed away from his caretakers, treating it like a game; he’d bite and nip for attention. His many other transgressions included counter surfing, chewing shoes and furniture, jumping on humans, and playing too aggressively with other dogs. “You’ve got this!” she added—optimistically, I thought.

Over the coming year, as we worked with various trainers around our Austin, Texas, home, Ernie’s more destructive puppy behaviors did subside, and I was able to eventually do away with his crate. His energy, however, persisted, and could skyrocket dramatically at any given moment. Houseguests triggered kangaroo-esque jumps on his hind legs, knocking over any unsecured objects or humans nearby. He seemed to perceive passing dogs (especially if they were big, white, and fluffy) and also city buses as either tantalizing playmates or his greatest enemies; spotting either on a walk meant lunging wildly, then performing a series of what looked like backflips on the end of his leash—though it was difficult to discern what was happening, exactly, in the cartoonlike blur.

More than once, upon detecting a dog outside, Ernie reacted so aggressively he broke through the living room window (thankfully, he only ever injured the glass). Another time, I made the error of letting him off leash in a wooded dog park—mistakenly thinking that, as Jeffrey always had, Ernie would stick close by. For the next hour, I anxiously traipsed up and down the trails, sometimes spotting a flash of brown deeper in the woods. Now and then, Ernie would appear on the path ahead, hold eye contact with me, then turn stubbornly away and dart off once more.

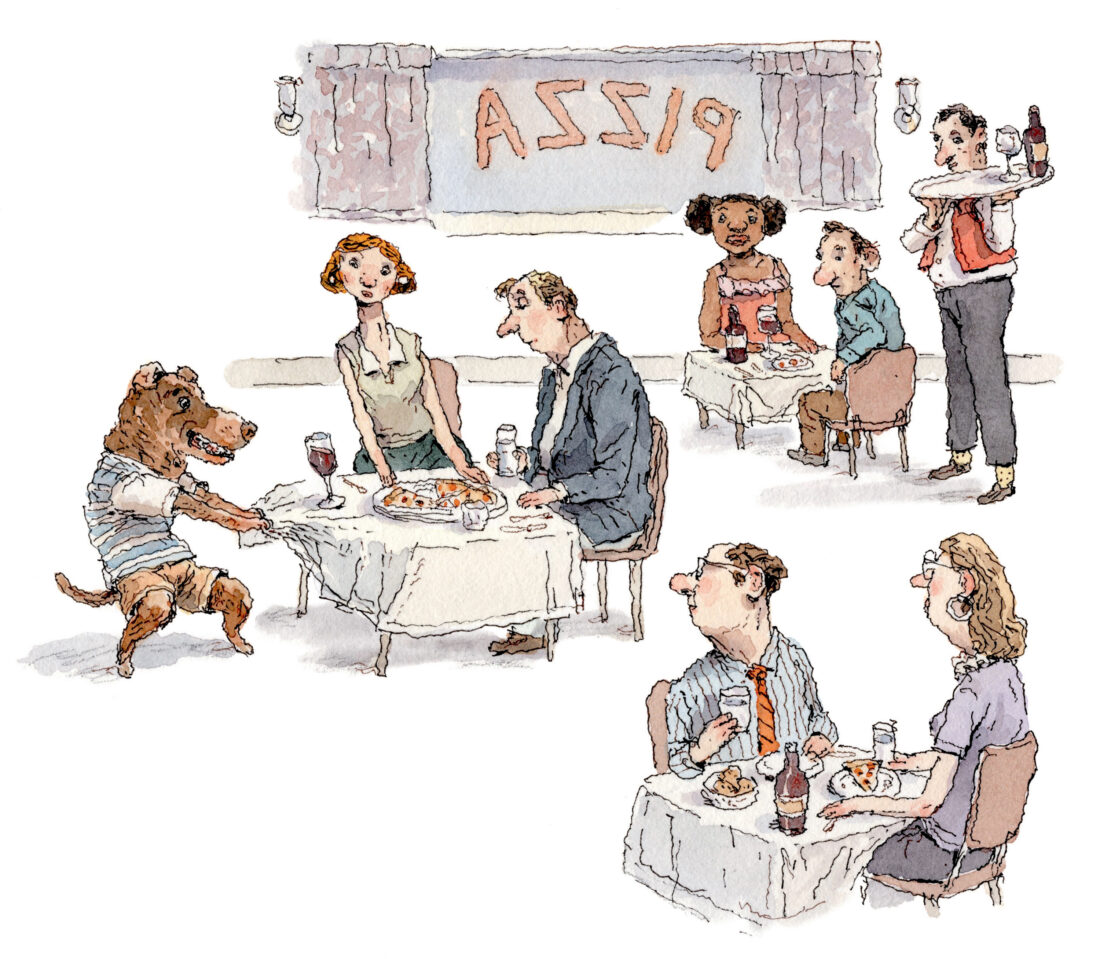

But if Ernie was the most mischievous dog I had ever met, he was also the most loving. On walks, he’d often take a liking to a stranger and abruptly sit down mid-sidewalk, eagerly wagging his tail, waiting for the person to pet him. If I found myself crying, Ernie would invariably rest a paw on me, or press his whole body against my legs in what I learned is a characteristic pit bull lean, his eyebrows knit in palpable concern. After my unlocked front door blew open in the wind and Ernie escaped, I got a call from the pizza place down the street. Ernie had slipped into the restaurant through the open kitchen door and trotted from table to table, greeting the diners, before the waitstaff finally noticed him.

I’d been walking, chasing, wrangling, and only semi-successfully training Ernie for more than three years when, the day after Austin went into pandemic lock-down, I was diagnosed with cancer. While friends generously helped care for Ernie, driving him to doggie day care on my chemo days or taking him to play with their own dogs, I was reluctant to burden anyone too often, and so he mostly remained home with me.

The toxicity of my chemotherapy accumulated, and the number of days I felt good between infusions shrank over the course of that pandemic spring and then summer. Some days, it was all I could do to make it a quarter of the distance Ernie and I normally walked in the morning, barely looping a city block. Not even halfway through, I’d pause at a park bench under a large pecan tree, bracing myself against it to rest. On the worst days, I’d feel so ill that I couldn’t even listen to music or watch television. Instead, I’d lie as still as possible on my small sofa, every part of me exhausted and hurting.

Ernie, typically so rambunctious, lowered his own energy levels on those days to meet mine. After a brief, slow walk, he’d jump onto the sofa with me, half of his sixty pounds squashed against the cushions, half on my body. When meds and fatigue sent me into a deep, twelve-hour sleep, I’d awake the next morning to Ernie curled close, snoring soundly.

I had spent those first years with Ernie learning, again and again, how to meet him where he was—in all of his personality and mischief—rather than where I had wanted him to be. Now, when I most needed both rest and companionship, he was doing the same for me.

In the fall of 2021, soon after the successful completion of my cancer treatment, Ernie and I moved to Brooklyn. We now take long walks along old tree-lined blocks, and I carry little bits of cheese or turkey to reward him for the moments he remembers to turn toward me, rather than leap maniacally toward a source of excitement—city buses, still, or the countless delivery drivers on mopeds who zip up and down the avenue. Recently, full of pent-up energy after a day of pouring rain, he took it upon himself to tear a gaping hole in my favorite linen bedsheets.

Such moments can feel frustrating, but a vivid memory from the spring of 2020, in the intense weeks that followed my diagnosis, often returns to me: One day, I arrived home from a doctor’s appointment and bent to greet Ernie, who wagged his tail with furious, uncontainable joy. I patted his drumlike torso, and the warmth of his body, its aliveness, suddenly struck me. As he leaned hard against me, I felt a wash of gratitude for this wiggly, wild creature—and for our shared mortality, making our time together all the sweeter.