My friend Max owns two blue heelers, both of whom are, she says, wicked smart. She once found herself apologizing to them: “I’m so sorry I can’t understand what you’re trying to tell me.”

That’s just one dilemma for those of us lucky enough to have experienced a smart and contemplative dog. These nonverbal companions simply cannot articulate the apparently complex ideas going on in their heads. From their perspective, conversations tend to be one-sided, and arguments brief and unsatisfying. Smart dogs are particularly frustrating, because we know they’re not trying to be difficult. They’re just trying to let us know their kibble bowl is empty, or that they need to pee, or that there’s a cane toad on the porch, but they have to rely on their dense human counterparts to understand what they’re trying to say. We are, more often than not, the slower-witted of the pair.

I should point out that I don’t ascribe this level of intelligence to any of the first seven dogs my wife, Judy, and I have had during our forty-five-year relationship, or to my beloved first dog, a black Lab who arrived when I was five with a unique SEC pedigree: Dad swore until his death that he bought Major from Bart Starr’s father-in-law. He and every dog since have been lovable and cherished.

But Scottie, our late and inscrutable rat terrier, was something else entirely.

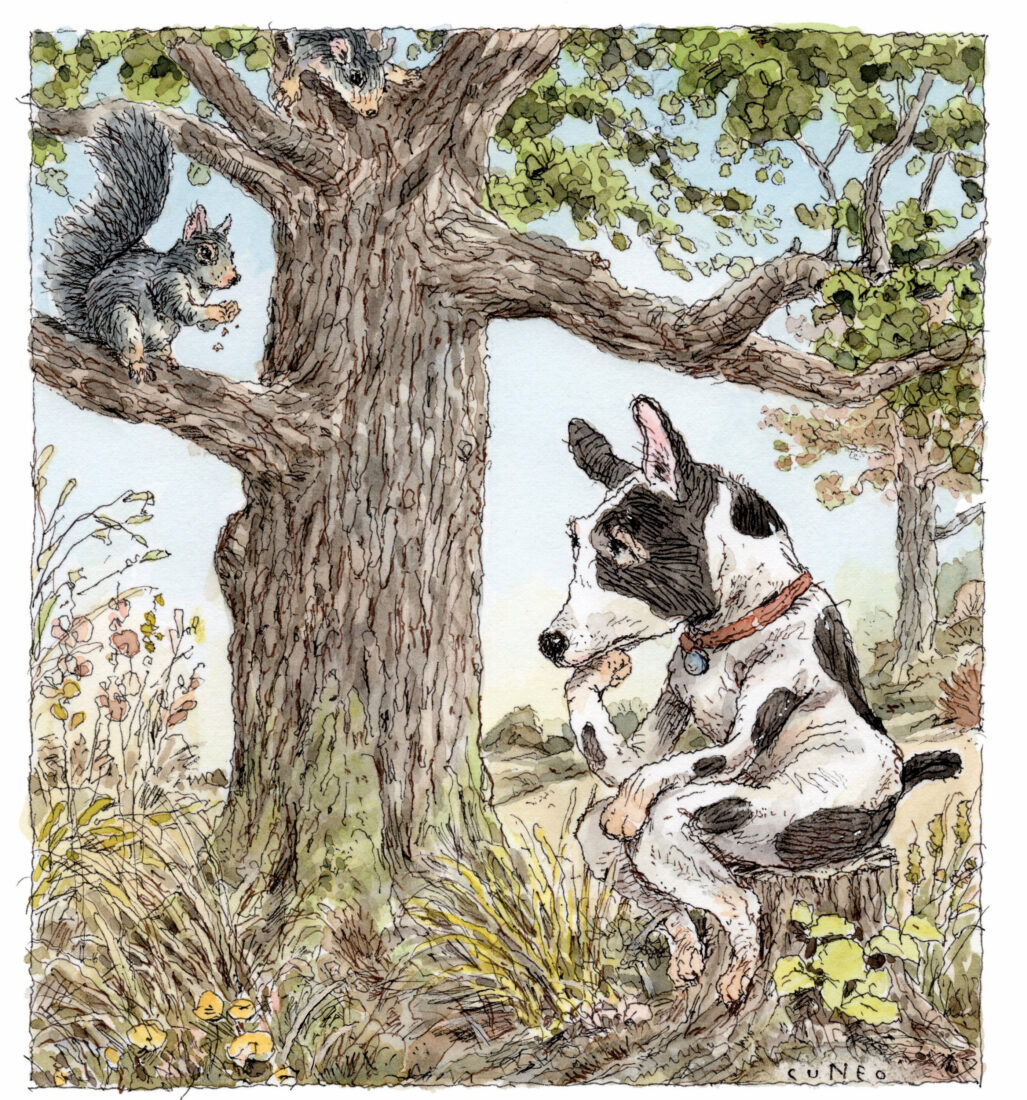

Shaped like a greyhound, colored like a Holstein, Scottie was an endlessly searching student of life inside a sleek, eighteen-pound bundle of fast-twitch muscle and sinew. It was obvious during our eleven years together that we were dealing with something greater than a mere dog.

Scottie was a thinker. When he wanted something, he’d stand squarely and silently in front of you—resolute, self-assured, seemingly impatient that he was not being understood. No whining. No barking. Just a silent stare as he waited for you to catch up to him. To see him perched on the center console of our car as the world spooled toward him through the windshield was to see an unmistakable intellect at work. Watching him, Judy often wondered aloud: “What does he think about?”

That he actually was thinking was never in question.

Maybe it had something to do with his upbringing. Our daughter’s flaky college roommate got him on a whim, and immediately began neglecting him. In time Lanie fell in love with the entertaining little leprechaun and paid her roomie sixty dollars to take him off her hands. Scottie was still a puppy, so Lanie would hide him in a backpack and take him with her to class. That’s how Scottie spent some of his early years, in college lecture halls.

After Lanie graduated, she and Scottie lived for a while in a sixth-floor walk-up, meaning that each walk or potty break meant six flights down, and six flights back up. Scottie, always opinionated, found this unsatisfactory, and soon came to live with us. He stayed for more than a decade.

Over the years, we noticed things Scottie did that we’d never seen in our other dogs. On road trips, for example, he actively participated. While befouling rest stops across the country during journeys south, north, east, and west, he proved himself a competent navigator through an unvarying routine. Anytime the car hit sixty miles per hour, he’d retreat to his blanket in the well behind the driver’s seat and ride happily for hours. But if the car slowed below sixty for an interstate exit ramp, or traffic, he would stir and climb forward into the front passenger seat to figure out what was happening. If the car slowed to about twenty, or stopped, he’d insist that my wife roll down the passenger-side window so he could thrust his nose into the onrushing air. This was Scottie’s way of orienting himself, of figuring out where we were. Pine? Deep South. Eucalyptus? Southern California. River? Colorado. Satisfied, he would retreat to the seat well and await the next checkpoint.

Lanie, who teaches hearing-impaired children with cochlear implants, once watched Scottie go through that routine and perfectly described what he was doing: “Processing, processing, processing…”

I vividly recall a conversation one morning as Judy and Scottie drove me to the airport. “We’re going to the airport,” she explained. Then she paused to enunciate, as if speaking to a child. “Air-port.” Amused, I said, “I’m not sure he really grasps the concept of commercial aviation.”

“You might be surprised.”

We once road-tripped with him to several national parks. One day’s hike led us past an information display about a specific type of oak, the acorns of which are a favorite food of chipmunks. Sensing a photo op for my long-running Facebook journal about the wee dog’s adventures, I asked Judy to boost him up for a gimmicky picture. She did so, and after I posted the image, I realized Scottie wasn’t looking at the vivid illustration of a chipmunk on the left, but rather at the explanatory text on the right. Could he actually be…? Nah.

Still, one of his longtime followers commented: “I love that he does his research.”

During a Western trip, we drove deep into Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park, then hiked to see one of the preserved cliff dwellings that housed the continent’s earliest inhabitants. Scottie spent a long time staring across a chasm at one precarious household carved into a steep canyon wall. You could almost hear him thinking: What did those people and their dogs do when they had to, you know, go?

Processing, processing, processing.

Eventually Scottie went into the security business. In 2016, we moved from the big city to more rural surroundings. The relocation required our pampered city dog to adapt to an entirely new life in the country, where he seldom needed a leash and constantly patrolled for invaders large and small. Scottie immediately assumed the responsibility of keeping our four acres safe from chipmunks, voles, squirrels, porcupines, stray cows, bears, foxes, deer, and elk.

He took the defender job seriously, often sitting for hours in front of a vole hole or staring up the trunk of a tree at an indignant, chattering squirrel. He once pursued a bull into an open field and held it at bay for several minutes, backing off only when the bull lowered its head for a charge. Once engaged, his focus was nearly impossible to break. We often had to coax him away from his sworn duties with a harsh word or a hitch-and-drag using the leash. He’d eventually comply, but as he was led away, he’d mutter in a way I interpreted as “Hey, I’m tryna work here.”

We’ve had two dogs since Scottie’s passing in late 2019, a peppy and equally diligent mini Aussie named Finn who came to us as a pup, and a gentle doorstop of an English Cream golden retriever named Callie whom we inherited from a niece who moved abroad. Both are fine companions to us and each other, and we love them dearly. They have enriched our lives in countless ways.

But they have no apparent ambitions. One of them eats poop. They do not and never will engage with the world the way our little thinking dog did. They’ll never glare into our souls as we struggle to understand the thoughts in their heads. They’ll never demand more intellectual engagement than we’re able to provide. They’ll never question our plodding incomprehension of their Big Ideas, because we’re pretty sure that, unlike Scottie, they’ll never have any.