Like millions of people who lost loved ones in World War II, Mabel Feil was desperately grieving her fallen soldier husband, Warren F. Feil, in the war’s aftermath. An Army private, Feil was killed in Germany on April 18, 1945—which happened to be his twenty-fifth birthday—just weeks before the Allies declared victory in Europe on May 8, 1945.

So when the Demopolis, Alabama, widow saw a letter in an August 1945 issue of Life magazine from the mayor of Maastricht, a city in the Netherlands’ southern tip, thanking U.S. soldiers for their service and sacrifice, Feil immediately wrote the mayor her own letter. She made a heartfelt request for a photo of her husband’s grave at the military cemetery where he was buried, in the nearby town of Margraten.

“I cannot begin to tell you how very much it would mean to me to have such a picture,” Feil wrote. “My husband and I were so young and he was my whole life to me. I know that he rests in peace and I have heard how beautifully the graves are kept and how the kind people of Holland go to the cemeteries and place flowers upon the graves. If only I could see for myself. The snapshot would help so much.”

As Feil’s letter noted, word of an extraordinary phenomenon taking shape in the Netherlands’ southernmost Limburg province had crossed the Atlantic: a collective effort to honor the thousands of American service members who died while liberating the Dutch from nearly five years of occupation under Nazi Germany by adopting the fallen Americans’ graves. Feil’s letter, which the Maastricht mayor passed along to his wife, also underscored just how profoundly such acts of commemoration could comfort soldiers’ loved ones in the U.S.

In early 1945, a group of Dutch civilians formed a committee and an official program, whose mission still flourishes eighty years later: All of the approximately 10,000 service members honored at what is now known as the Netherlands American Cemetery—8,291 are buried in graves with Italian marble crosses and Stars of David; another 1,722 names are inscribed on the Walls of the Missing—have been adopted by local families, individuals, or schools. (There’s also a waiting list of hopeful adopters.)

Adopters, many of whom have kept the same soldier in their family for generations, visit the cemetery regularly, usually on significant dates, including the soldier’s birthday or date of death, U.S. Memorial Day, and Veteran’s Day. They often come bearing flowers and sometimes a photo. It’s a moving aspect of history that many first-time visitors to the cemetery—and even seasoned war experts—are surprised to learn.

In 2016, the Dallas-based historian Robert Edsel was one of them. The co-author (with Bret Witter) of the best-selling 2009 book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History says he was “astonished” to learn of this long-standing commemoration by the Dutch people—and how little known it was outside the region. (His book about a team of scholars who rescued art stolen by the Nazis was made into a 2014 movie starring George Clooney and Matt Damon.)

“They said, ‘We will watch over your boys—and women, there are four women buried at Margraten—like they are our own forever,’” says Edsel, who recently released a new book, Remember Us: American Sacrifice, Dutch Freedom, and a Forever Promise Forged in World War II (also with Witter, who lives in Decatur, Georgia). Available in both English and Dutch, the book is dedicated to the longstanding tradition of commemorating fallen service members in the Limburg province. “That’s what drew me to the story. I’ve tried very hard to … honor the Americans buried in Margraten and the Dutch who have loved and honored them faithfully for eighty years.”

The American Battle Monuments Commission maintains the beautifully manicured 65.5-acre Netherlands American Cemetery. The federal agency manages memorials worldwide, more than half of which are in Europe. Their most visited plot is Normandy American Cemetery, which honors more than 10,000 fallen Americans. In addition to Margraten, adoption programs exist at cemeteries in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom. However, the ABMC does not oversee any grave adoption programs; instead, European nonprofit organizations and individual volunteers take on these heartfelt efforts.

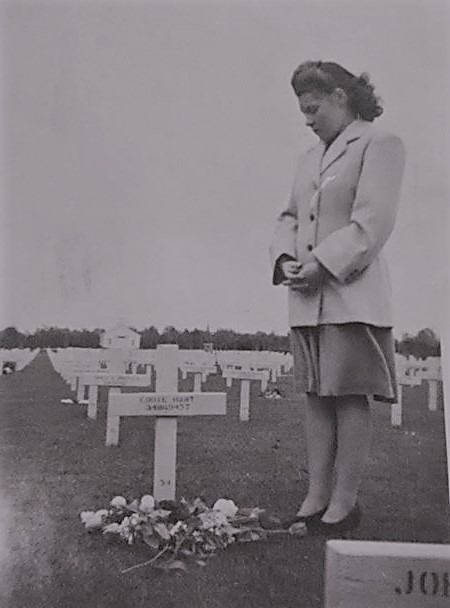

Some adopters stay in contact with relatives or loved ones of the fallen Americans, which can be deeply moving for both parties. Debbie Holloman, a retiree who lives in Virginia, grew up hearing stories about her uncle, Eddie Hart, a private first class in the Army and a Purple Heart recipient who was killed in action at age twenty-two in April 1945. A now-deceased Dutch woman named Betty Vrancken adopted Hart’s grave at Margraten, and Holloman still remembers how grateful her grandmother—Hart’s mother—was to meet Vrancken for the first time in 1967.

For the past decade, Holloman does what she can to ensure the memories of fallen Americans like her uncle are never forgotten. In addition to volunteering for nonprofits like the Fields of Honor Foundation and Faces of Margraten, which aim to find information and photographs of U.S. service members memorialized at six U.S. cemeteries in Europe, Holloman acts as a liaison between adopters and soldiers’ relatives in the U.S. She estimates she’s helped about two hundred adopters and families make contact, mostly for service members from Virginia and North Carolina who are honored at Margraten and Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery in Belgium.

“We don’t know what would have happened to the world if they had not sacrificed their lives,” says Holloman, who will visit both cemeteries this Memorial Day. “We don’t know what kind of regime we’d be living under now. It’s important for Americans to know that there are people around the world who still honor and appreciate the sacrifice that was made eighty years ago.”

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.