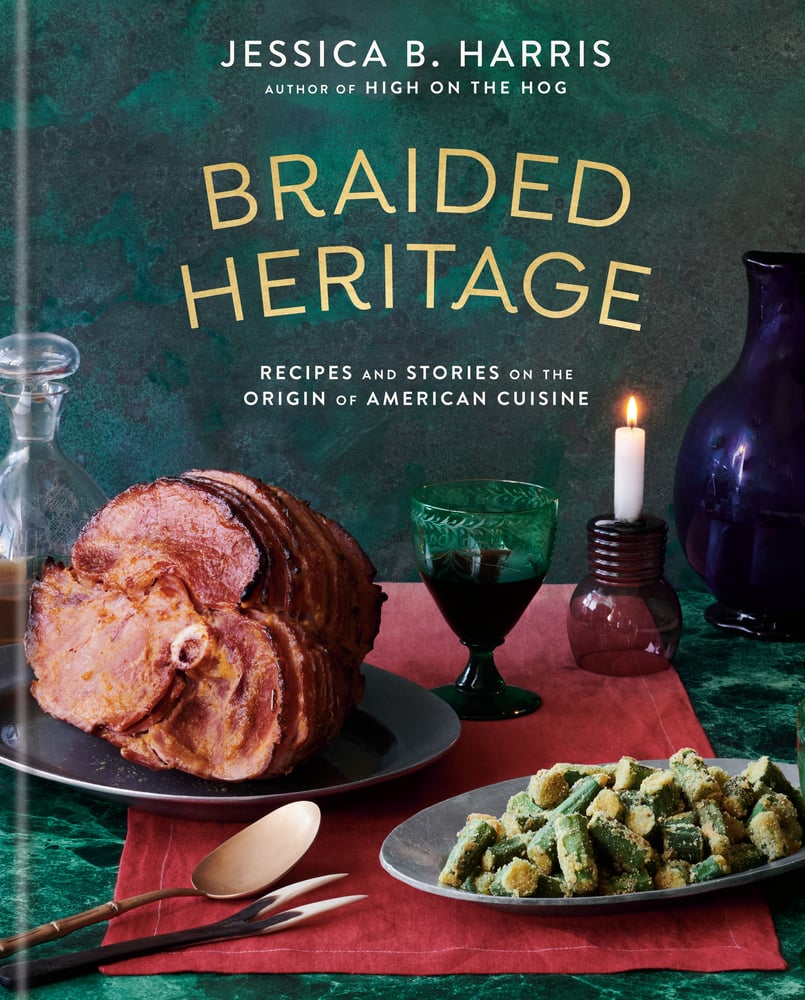

Most cookbooks begin with tips on setting out ingredients or cooking tools, or setting the table. Not Jessica B. Harris’s Braided Heritage. “Let’s begin,” she writes, “by resetting the notion of history.” This might seem a tall order for a weeknight supper—kids looking up from homework with when’s dinner faces, spouse impatiently clocking a second cocktail—but fear not: Woven into Harris’s acute reconsiderations of American cuisine are threads of simple deliciousness.

Harris’s thesis goes like this: The strands of the nation’s cookery have never run parallel. Rather, they’ve been braided from the beginning. “By the year 1776,” she writes, “the place that would become the United States of America was not just about Pilgrims and plantations, but was an increasingly rich mixture of Native Americans from large swaths of the Eastern seaboard, multiple European communities of different classes, and Africans from western and central parts of that continent eating foods as diverse as corn pone, okra soup, and bean pottage.” Those European settlers, Indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans coexisted uneasily, to grossly understate; on the plate, however, their cultures came together magnificently.

Harris offers ninety-four recipes as proof, including maple-and-spruce-braised rabbit with nixtamalized corn; Dutch coleslaw, fattened with melted butter rather than mayo; beer-battered maple leaves with cranberry syrup; Huguenot Torte, a South Carolina specialty Harris describes as “the love child of apple crisp and pecan pie”; okra fritters; and, of course, that emblematic American staple, apple pie. “The more that we acknowledge that the history—both culinary and literal—of this country is the result of a…complex intertwining of cultures, the sooner we can, all of us, whatever our origins, come together around our bountiful communal table,” she writes. “And perhaps then we can all appreciate our good old-fashioned American apple pie to its fullest.”

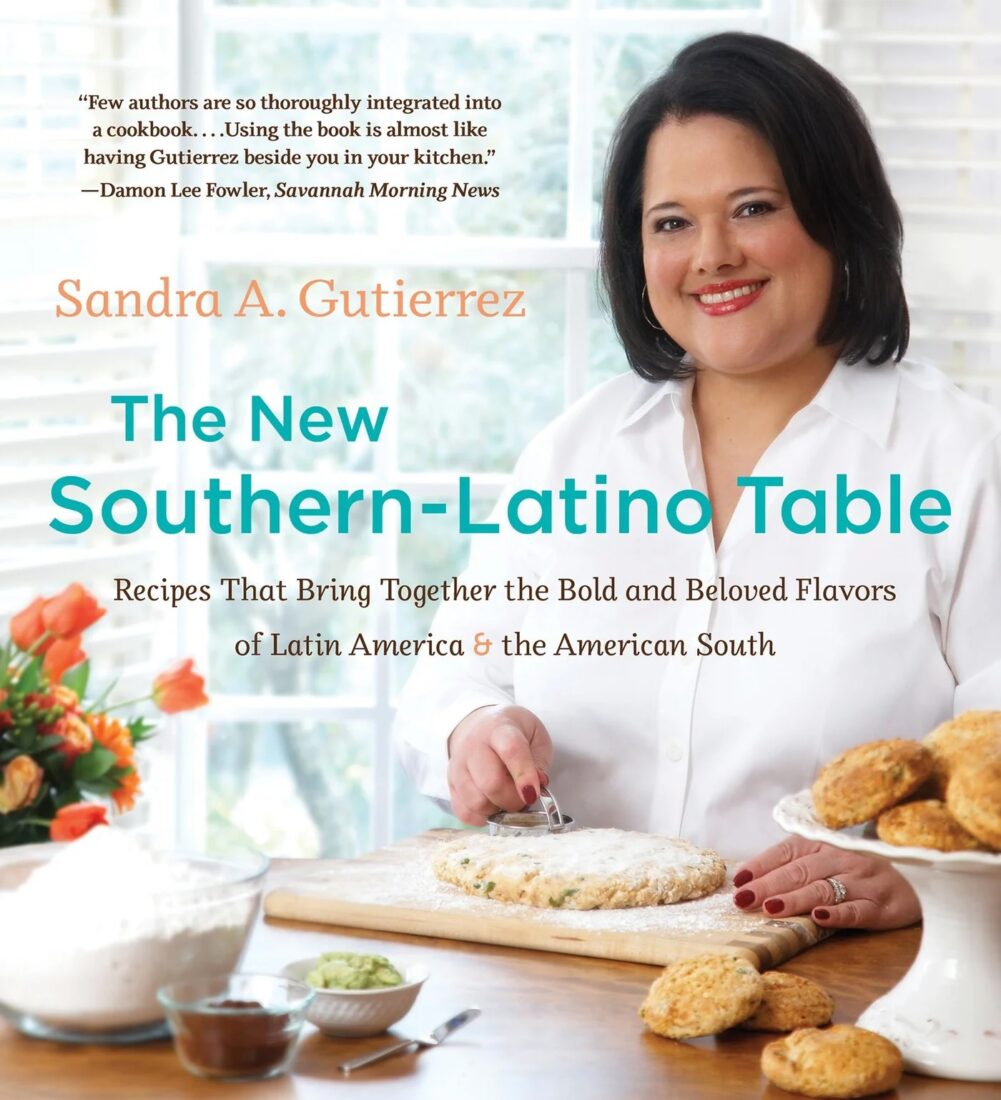

Perhaps nowhere has the country’s culinary heritage been more braided than in the South. As some of this year’s standout cookbooks demonstrate, the South’s is a fusion cuisine that’s still fusing. Take Sandra A. Gutierrez’s The New Southern-Latino Table, for instance. First published in 2011 and rereleased in paperback this year, the Guatemalan American, North Carolina-based Gutierrez maps the intersection of New and Nuevo South. Chipotles find their way into pimento cheese; masa harina, not cornmeal, coats her fried green tomatoes; and dulce de leche commences a sweet friendship with bourbon.

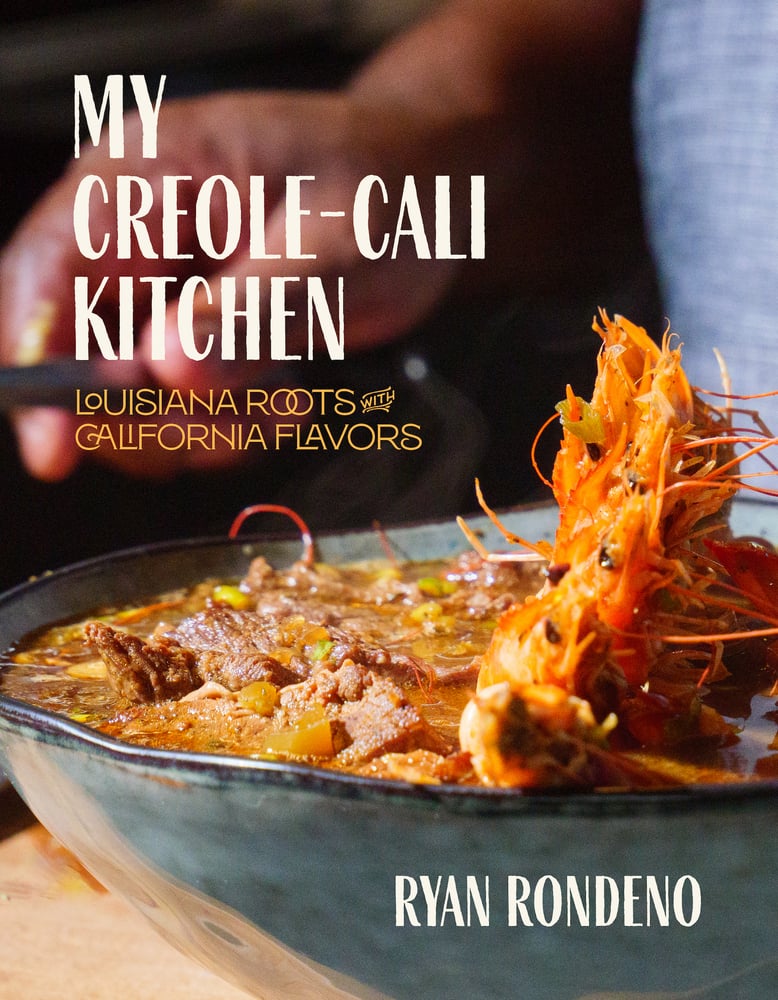

This kind of fusion often happens regionally or locally. Other times, it’s personal. Consider Ryan Rondeno, a Louisiana native whose résumé boasts a Michelinworthy list of New Orleans restaurants (Gautreau’s, Peristyle, Commander’s Palace). In the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, though, Rondeno eventually drifted to Los Angeles, where he worked as a private chef while developing the ethos on display in My Creole-Cali Kitchen. What happens when Creole cooking travels I-10 all the way to the Pacific? Fried crab fingers get glazed in Thai chile sauce. Arugula pesto and apricots sizzled in duck fat brighten roasted Brussels sprouts. Underneath crabmeat beignets lies a golden beet and burrata salad dressed with anchovies. Yuzu marmalade makes a cameo in a 7UP cake.

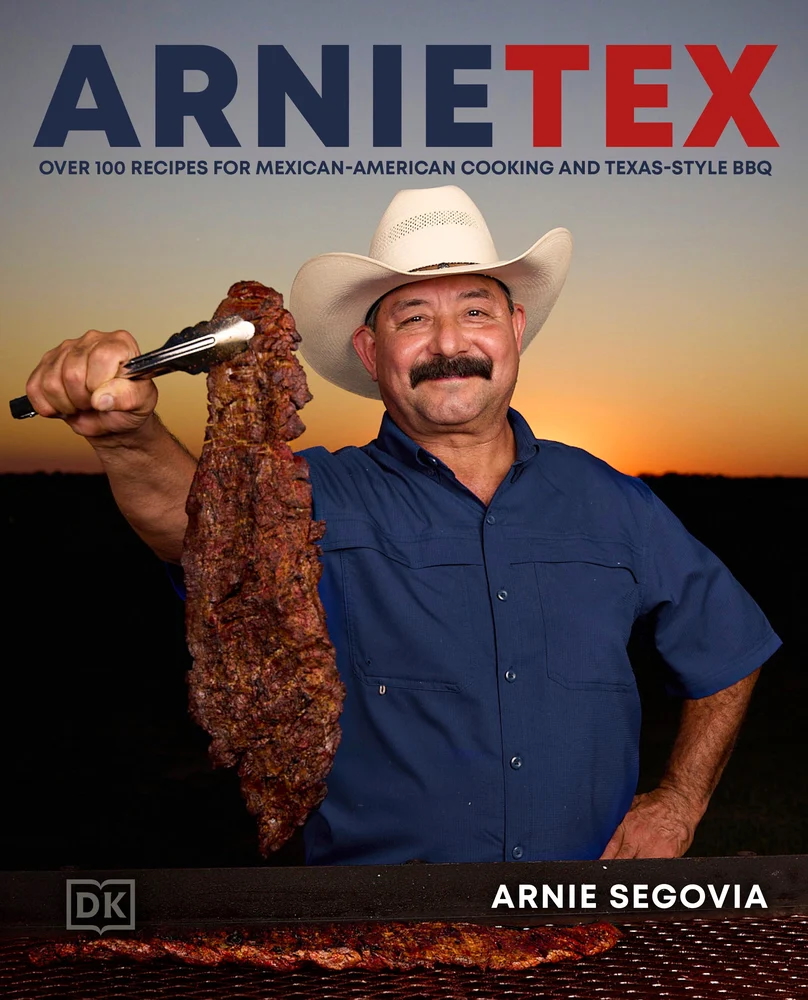

Tex-Mex, of course, is one of our premier fusions. And Arnie Segovia’s ArnieTex is as good a guide to it as we’ve seen in years. Segovia, once a South Texas car salesman, found renown on the competitive brisket circuit before earning wider fame by taking his barbecuing smarts online with smoker-side YouTube tutorials and backyard Tik-Toks. Segovia’s cookbook debut, subtitled Over 100 Recipes for Mexican-American Cooking and Texas-Style BBQ, is as warm and engaging as his mustachioed screen presence. Definitive versions of Tex-Mex familiars are here—enchiladas, chili, tamales, fajitas—but also more-local fare: There’s Salsa Tuétano, slickened with roasted bone marrow, among Segovia’s seventeen salsas; cachetadas tacos, in which thinly sliced meat is briefly seared, then slapped into a warm corn tortilla; and discada norteña, which sees meats and vegetables griddled on a big disco until it resembles an edible kaleidoscope.

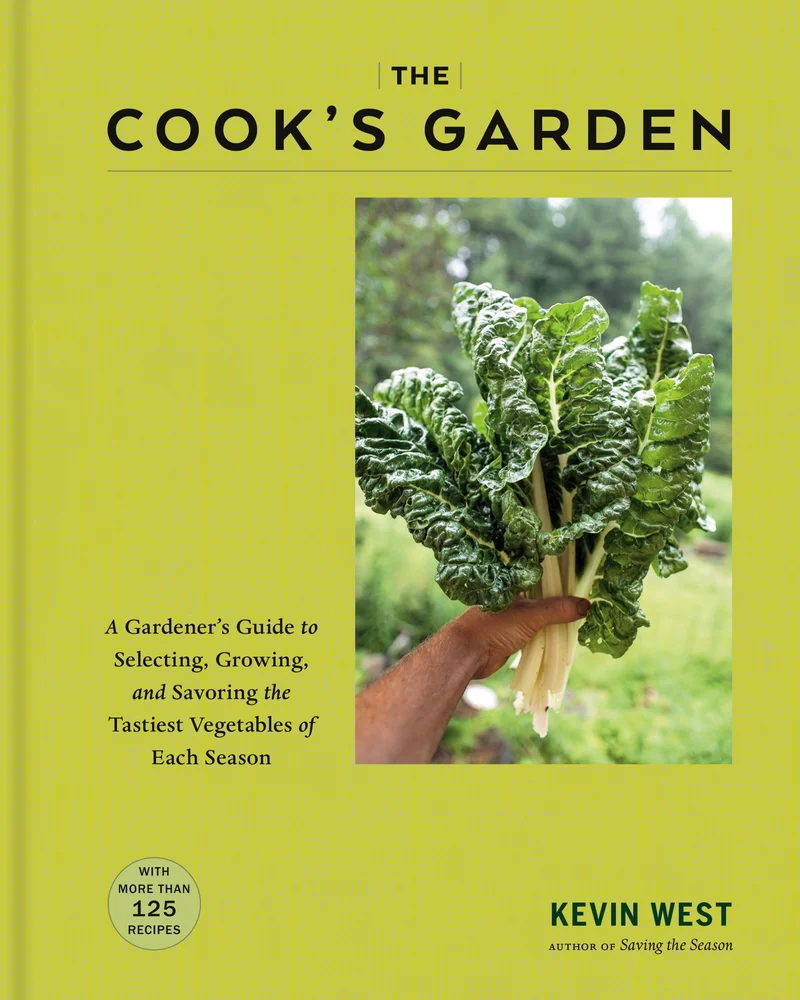

Finally, let us not forget what Thomas Jefferson called “the culture of the earth,” or agriculture. That’s where Kevin West’s thrilling The Cook’s Garden comes in. The “grandson of East Tennessee farmers and Smoky Mountain hillbillies” shepherds readers not from farm to table but deeper: from seed to serving dish. His slab of a book guides you through planning a garden, tending it, and, with 125-plus recipes, cooking from it—gorgeously, often sublimely. These aren’t the flavor-swarmed dishes you see on Instagram in which, say, zucchini cowers under onslaughts of harissa, za’atar, cilantro, and feta. West’s zucchini, fresh from picking, is sliced raw, like carpaccio, and served with a savory tonnato– inspired sauce for dipping. He sautés fresh corn over a whisper of heat in butter until barely cooked, then gilds it with a schmear of crème fraîche and basil chiffonade. He throws a few Nicoise olives into a summer sauté of greens and tomatoes, for briny flair, but otherwise lets the vegetables shine. What to do with a summer surfeit of tomatoes? West has a dozen ideas, and, yes, a tomato sandwich (using “squishy store-type bread”) is first. The garden might be the most fitting metaphor for the South’s culinary braids: okra from Africa, tomatoes from Mesoamerica, onions and cucumbers from Asia, all of them planted together, all feeding not just the belly but the soul.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.