It started as a sound—a low-pitched, primeval snarl—that drifted into our front yard from the house next door. Then came an ascending sequence of snarls, and then the ragged noise of full combat.

“Oh, good Lord,” my father said, with a mixture of annoyance and resignation. “There they go again.”

In the next instant we were sprinting toward the sound. My father grabbed the hose. I laid hold of a broom and a towel from the line—anything to stop the fight that was now raging between our dog, Ruffy, and the neighbors’ dog, Gulliver. We finally managed to pull them apart. There were torn ears and torn gums and a bit of blood on the ground. They were dragged away, breathless and wild-eyed, spoken to harshly, and tied up for the rest of the day.

All of this happened a long time ago, in a land far, far away where there were only three television channels and dogs roamed free and no one spayed or castrated any of them. But the fight will serve as your introduction to Ruffy, the principal dog of my childhood, a strikingly handsome eighty-five-pound male who was a cross between his collie mother and an unknown father who may or may not have been a Saint Bernard. He was a sort of neighborhood swashbuckler: a free spirit who made his own rules and happily followed them. Whatever there was of the rationalist in him—the sort of dog who quietly behaved himself and got rewarded for it by his grateful master—was greatly outweighed by his buccaneering impulses. Ruffy never quite grasped the idea of consequences.

He did not see any problem, for example, with the notion of removing a large steak from a neighbor’s grill while it was cooking and dragging it off across the lawn, in spite of the sharp smack that such behavior guaranteed. Or with breaking down a screen door to gain access to an obscenely expensive purebred Irish setter named Guinevere whose offspring were destined for the Westminster show, and mating with her in the kitchen. Thankfully the congress did not result in a litter of puppies.

Or with crossing county lines in search of love. I remember my mother getting a phone call from an angry dog owner who lived fully seven miles away, complaining that our dog was “bothering” his female dog, who happened to be in heat. Ruffy had managed to defeat the owner’s fences and gates, and no amount of shooing would make him leave. We retrieved him, only to receive an even angrier call the next day. “Your damn dog is still here, lady,” the man said. “Come get your damn dog.” We got many calls like that.

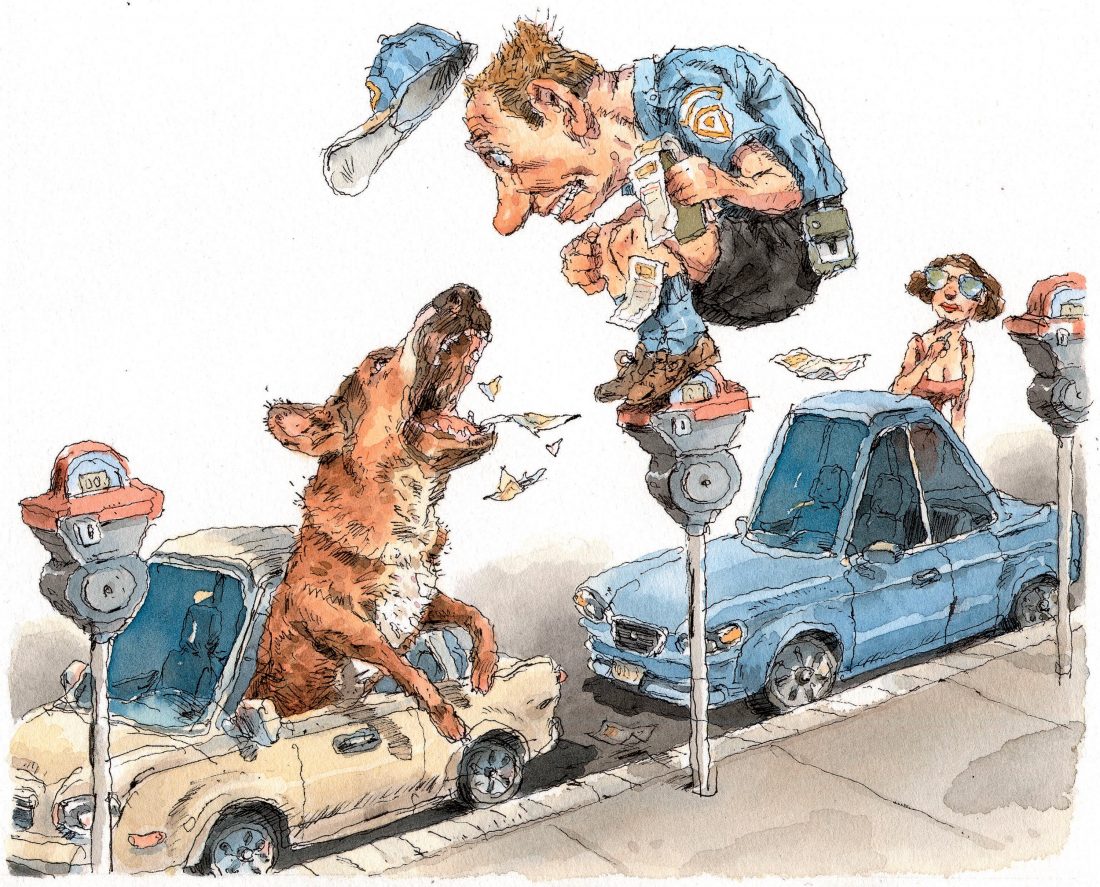

The damn dog had other bad habits, too. He chased cars, his teeth coming so close to the tires that it seemed impossible that he would not be pulled under them. He miscalculated only once, as far as we knew, with a motorcycle, and was rolled hard. He survived with minor scratches. He terrorized garbage collectors and meter readers. He dug holes around my mother’s juniper bushes—massive, patiently engineered excavations that took hours to refill. On the tennis court, Ruffy’s idea of fun was to intercept balls in midflight and then play keep-away as you chased him. When you got the ball back, if you got it at all, it was a gooey, drool-sodden sphere of mush that was useless for play. Our tennis partners would say: “Ew. Gross.”

From the preceding descriptions you have most likely come to an obvious conclusion: Ruffy was an unneutered, free-range, pain-in-the-ass male dog.

You would not be wrong.

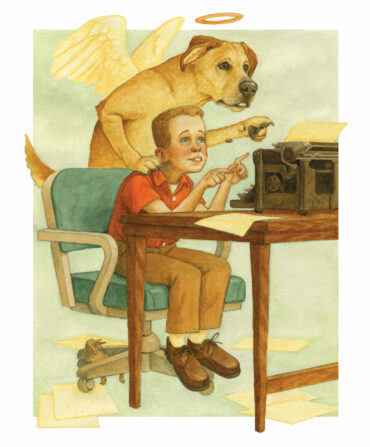

But you would be missing another important truth. For in spite of his elaborate self-indulgence, he was also the best and most beloved family dog I or my four younger siblings have ever had, and that includes all of the dogs we have collectively owned as adults. How could this be so? Because whatever adventures and personal entertainments Ruffy pursued in life, we also knew that his first choice was always us: the children. Plundering Guinevere, stealing steaks, digging in Mom’s garden, and fighting with Gulliver were his hobbies, his off-hours entertainment, things he did, I suppose, when he was bored.

His main job, which he took quite seriously, was being the Gwynne family dog.

This meant that, most of the time, he was with us five kids. He followed us everywhere. He was like Ruth in the Bible: “Whither thou goest, I will go.” When my sister took her horse on long rides through nearby orchards, Ruffy followed diligently and selflessly behind, no matter how many miles she rode or how hot or cold the weather. Sometimes he caught a hoof for his troubles. He followed all of my siblings around the neighborhood. At a nearby skating pond he would do a trick that we all remember with gem-like clarity: With three or four of us hanging onto his tail, he would begin to move forward, slowly gain momentum, and eventually break into a fast trot. Soon he and his whooping passengers were whizzing down the ice as the neighbors looked on in amazement.

At that same frozen pond, my brother once fell through the ice. He found himself underwater, looking up at the sheet of ice above him. Suddenly that ice shattered, and Ruffy appeared beside him in the water. It was unclear what the dog was trying to do, but he clearly understood that he had to do something. My brother’s friends pulled both of them out.

Sometimes, of course, we did not want to be followed. In summertime, Ruffy came down to the beach with us to our boats and, if not invited aboard, would take off in pursuit: a lone collie mix chugging along after our sailboat in the channel with the big motorboats. We thought he was going to drown or be run over. We usually had to bail him out. In the car, where he loved being with us, he was famous for his weapons-grade flatulence and the cataracts of drool that would come forth when the rest of us were eating lunch. Then there were the tennis courts, where I think the main problem was that we weren’t playing with him.

Ruffy was also our protector. When horseplay in the yard turned too rough, he would very deliberately and gently place his mouth around the forearm of the offending party. The implication: You’re going a bit too far. He once cornered two men in our driveway who, as it turned out, were carrying stolen goods from the house next door. When I came upon the scene, my uncle and father were standing on one side of the driveway, the intruders on the other. Ruffy’s fangs were fully bared and held an inch away from one of the men’s legs. The man kept saying: “Get your dog away from me.” My father refused until they dropped what they were carrying. Ruffy once fought a bloody draw with a forty-pound raccoon on our screen porch.

He died at the age of fourteen in 1976. I was twenty-three at the time. My youngest sibling was twelve. None of us could quite believe it. None of us could remember a time when Ruffy was not there. He had suffered from heartworm. The veterinarian had told my parents that the reason he had to be put down was that his heart was three times normal size.

Any of us could have told him that.