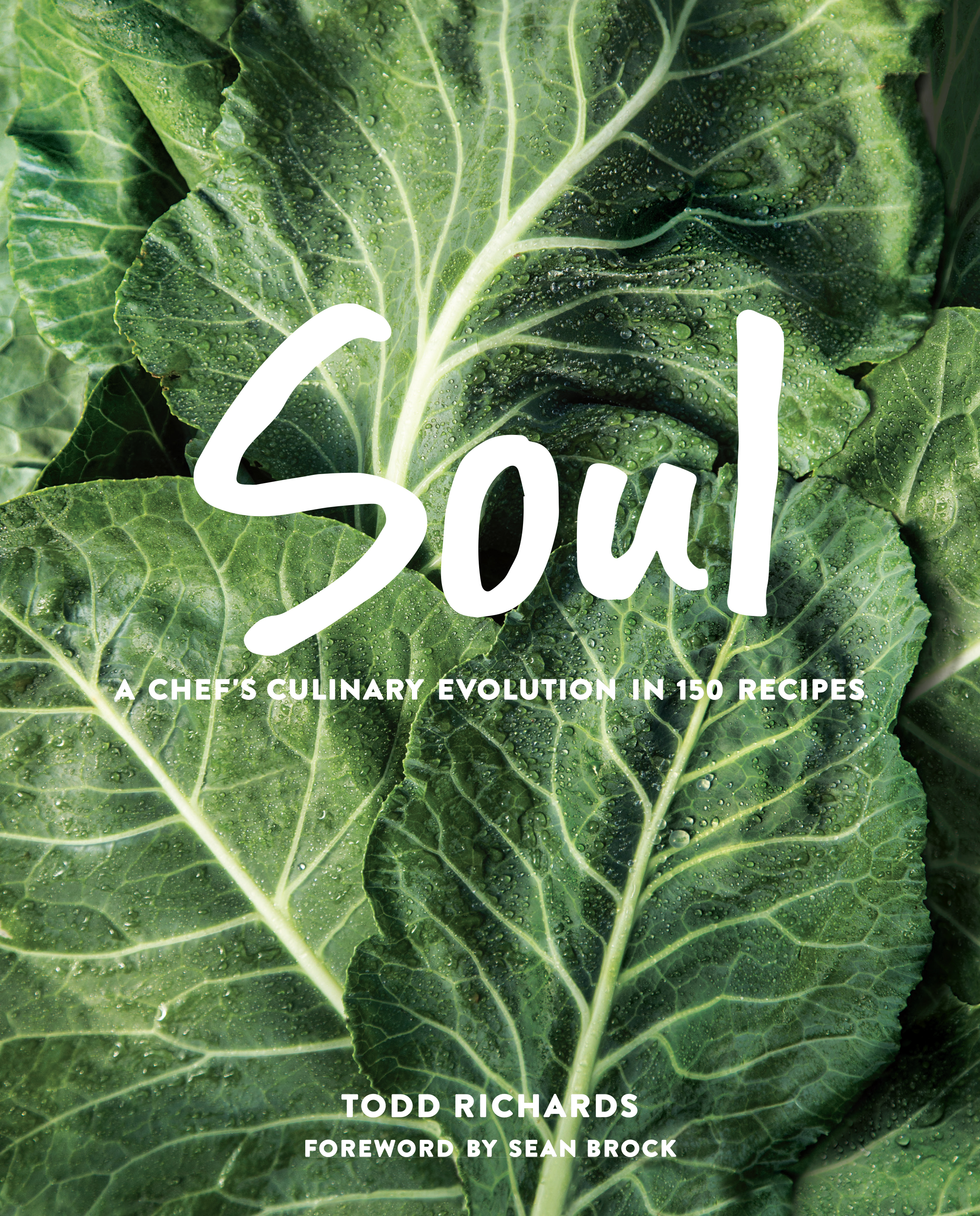

Todd Richard’s collards are in your face: The cover of his new cookbook, Soul: A Chef’s Culinary Evolution in 150 Recipes, is a close-up of dewy collards that are so vivid you expect to be able to feel the velvety leather of the leaves. If you miss the point, open the book. The very first chapter is all collards, with recipes that take them to places you may never have considered: Collard pesto with oysters. Collard waffles. Collard ramen.

Yes, this is a man who takes his collards seriously. But it’s not just collards. Instead of the usual lineup of appetizers, sides, and main dishes, the chapters in Soul are focused on ingredients. There’s a whole chapter just on onions—who does that?— and another on melons. Lamb, a meat that receives precious little attention in the South, gets its own chapter, while pork has to share a chapter with beef.

Richards can be unexpected. Born and raised in Chicago in a family that believed in exploring the world, he came to Atlanta in the 1990s looking for a job in the music industry, ended up in a grocery store meat department, and somehow followed that with a job for the influential African-American chef Darryl Evans at the Four Seasons Hotel. After a lengthy list of experiences—the Ritz-Carlton, The Pig and the Pearl, and the development group behind One Flew South, among others—he has settled in with Richards’ Southern Fried in the Krog Street Market.

We caught Richards early on a Saturday—he’d already been out and about for hours—to find out more about Soul. Keep reading below, and to sample two recipes from the book: Shrimp and Grits with Grits Crust and Grilled Peach Toast with Pimento Cheese.

In your book, you always spell “Soul” with a capital S. What’s the difference between Soul with a big S and soul with a little s?

It really comes down to American relevance to me, that Soul is a cuisine that belongs in the same place as French cuisine or Italian cuisine or Japanese cuisine. It requires a great amount of cooking and ingredients, but we charge the absolute least for it.

Do you consciously think about breaking rules and about what should fit into the canon of Soul cooking?

Soul food is a genre that has always broken the rules. Look at something like chitterlings that no one ever thought should be good, but they can be delicious. Soul food has done that religiously. Look at the use of watermelon rind [as a pickle]. That was a traditional way of using it and preserving it in Africa, instead of just throwing it away. Soul food is about breaking the rules and mashing things together that wouldn’t be commonplace.

When do you surprise yourself in the kitchen?

The biggest surprises for me are the things I eat all the time. I can eat all the delicious things in the world, but I gravitate back to scrambled eggs and roasted potatoes. I cook extravagant things for everyone in the world, but I cook the most basic things for myself.

Your book is broken down by ingredients, instead of styles or types of dishes. What does that say about how you approach cooking?

It’s that food can always evolve into something else. Foods that start one way can go into different genres. Like my Collard Green Ramen: That’s how I grew up. My mom loves [Asian] takeout, like noodle soups, and my frugal dad never threw anything out. So [leftover] collard greens were always on the table with noodle soups and things like that. Those ingredients always led to other dishes.

Your path to chef wasn’t a straight line. Are you surprised by where you ended up?

My family was always talking about reading. And we utilized reading as a way to explore the world, and then we followed it up by traveling to these places we read about. Food was always the focal point of those discussions. So it makes sense to me that I ended up as a chef. To be an author is a surprise. I take it as a humility that someone is interested in reading something I wrote, rather than taking something I put on the plate.

There’s so much conversation now about what we need to do to get more black chefs and black-owned restaurants. Where does it start and how do we fix the system?

I think [it] starts with black chefs. We have to network and support each other more, economically. We can’t ask others to do things that we aren’t doing ourselves. Second, we have to actually own more restaurants, and that comes with lending practices that are sound and reasonable. Third, especially in areas of new development, is that the model has to change for restaurants to be successful, because money-grabbing real estate is a right-now thing that’s about being profitable right now. The [James Beard Foundation] awards this year is proving that the balance is coming. There’s more diversity [in the awards] this year, absolutely. It’s starting to happen. The South is leading the diversity movement.”

Kathleen Purvis is the food editor of The Charlotte Observer and the author of three books, including the newly released Distilling the South.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.