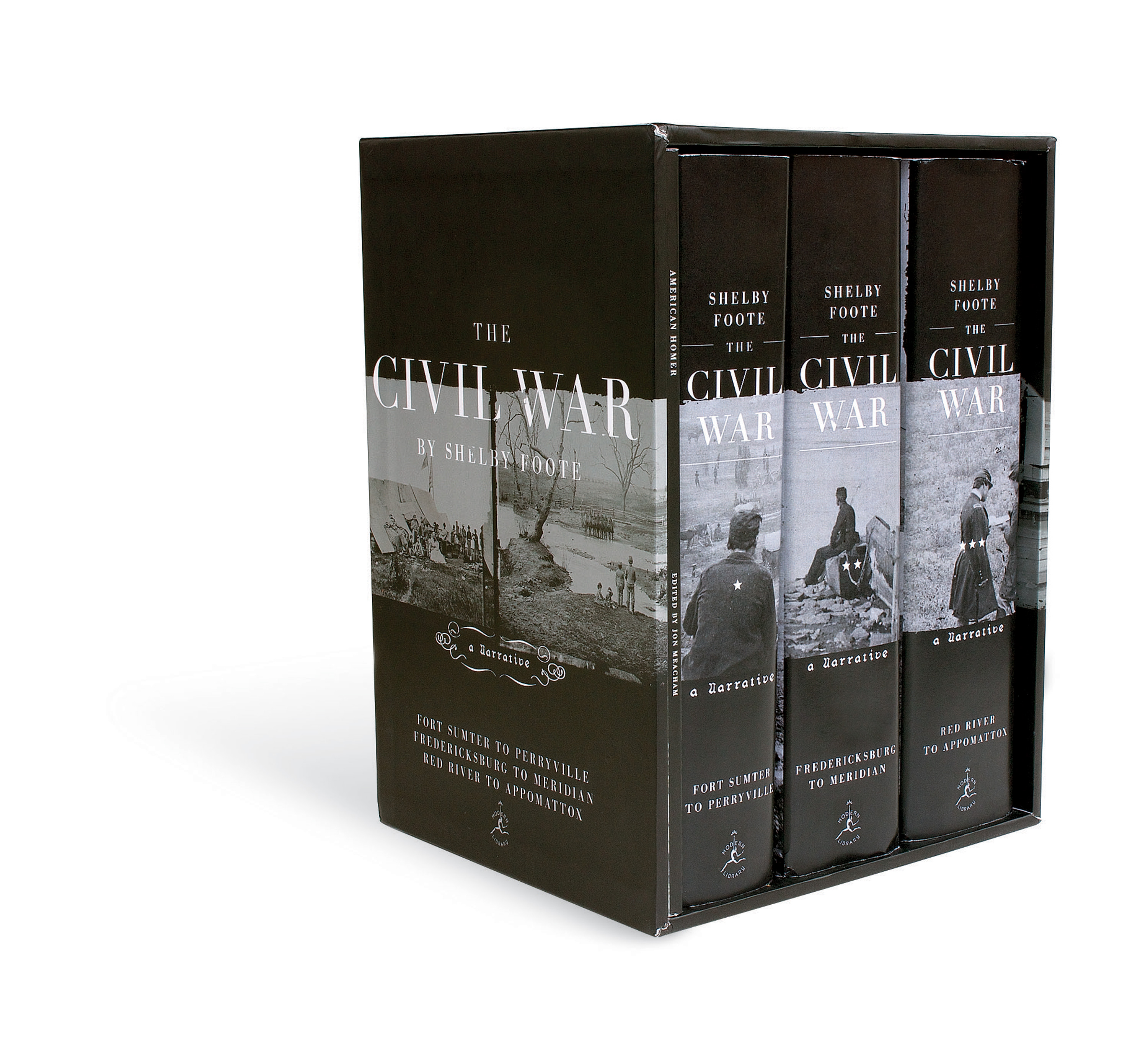

It was supposed to be a brief assignment—eighteen months or so, tops. In 1954, with the centennial of the end of the Civil War approaching, Bennett Cerf, the president of Random House, wrote the novelist Shelby Foote to propose a “short history” of the conflict. In midsummer the author traveled from his home in Memphis to meet with the publisher in New York, and the two came to terms. The target was 200,000 words; the advance, four hundred dollars. For Foote the plan was to get the book done fast and return to writing novels. “Fiction is hard work,” he recalled thinking; “history I figured, well, there’s not much to that.”

Foote was then thirty-seven. By the time he finished the third volume of his The Civil War: A Narrative, he would be fifty-six. In a notable case of literary understatement, Foote later observed, “It expanded as I wrote”—ultimately to just over 1,500,000 words, or, as Foote said, “a third of a million longer than Gibbon’s Decline & Fall, which took about the same length of time to write.” The war had come alive to him—he heard the hoofbeats and smelled the gunpowder and felt the anguish and the anxiety of Lincoln and Davis and the hundreds of thousands of unknown soldiers. “Don’t underrate it as a thing that can claim a man’s whole waking mind for years on end,” Foote wrote of the war.

Now, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the war, Foote’s masterpiece is getting a new look from readers in search of the truth about a seemingly distant conflict so encrusted in myth. Written in longhand in his house in West Tennessee, The Civil War is a twentieth-century book about a nineteenth-century clash that resonates still in the twenty-first. “The further I go in my studies, the more amazed I am,” he told Walker Percy in 1956. “What a war! Everything we are or will be goes right back to that period. It decided once and for all which way we were going, and we’ve gone.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said that there is “properly no history; only biography,” and to reread Foote is to see how the greatest historians are those who recognize that the past, like the present, is shaped by flawed, flesh-and-blood individuals, from presidents to foot soldiers. “The whole thing is wonderfully human…. In that furnace (the War) they were shown up, every one, for what they were.”

Born on Friday, November 17, 1916, in Greenville, Mississippi, Shelby Dade Foote, Jr., grew up in a relatively cosmopolitan atmosphere—or at least cosmopolitan by the standards of the early-century American South. Foote had Jewish ancestors in a time and place where Jews were broadly accepted in the social and cultural circles of certain Southern cities. Greenville was one of them (Foote later remarked that there were more Jews in the Greenville Country Club than there were Baptists). His father was the son of a lost Delta fortune, and one suspects that Foote’s tragic view of the world likely came in part from the saga of the Foote clan.

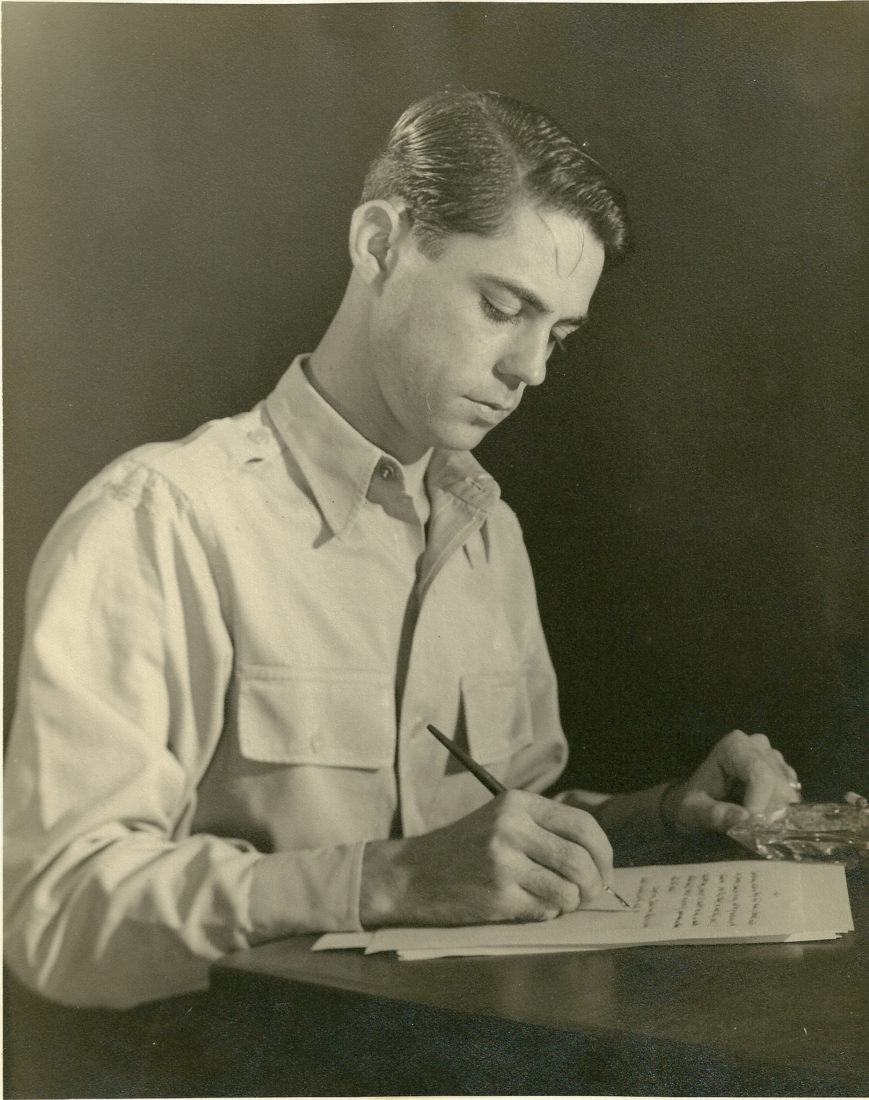

Photo: Huger Foote

Foote in New York City, 1999.

Shelby Jr.’s great-great-great-grandfather had bad luck back in Virginia, losing valuable tobacco land in Prince William County, and later generations gambled away the family’s sprawling Mississippi Delta plantations. Loss, then, was something young Shelby understood in his bones: It was an intrinsic element of his ancestry, the central fact of his paternal history.

His forebears fought for the Confederacy and engaged in the grim politics of Reconstruction Mississippi, but the defining influence in Foote’s youth—and thus in his life—came less from tales of Southern sentimentality and more from talk of literature, art, and philosophy in the house of William Alexander Percy, scion of a Delta dynasty and uncle of Walker. Will Percy was a planter-poet who took Walker and his brothers LeRoy and Phin in after their mother’s death, and Mr. Will, as he was known, asked young Shelby to come over to help entertain his young kinsmen when they arrived from Athens, Georgia.

The Percy salon fundamentally shaped Foote, who decided to become a novelist. His early books, particularly 1951’s Love in a Dry Season, were good but achieved little commercial success. He also had an expensive tendency to go through wives, creating obligations for alimony and child support. On the occasion of his third marriage, Foote wrote,“I cannot function outside the married state, no matter how much I’m galled inside it. (Nothing special about that. I think it’s true of most people: women as well as men.)”

Though he dropped out of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Foote was a literary man by inclination and training. One of the great readers of his age, Foote consumed Proust, Hemingway, Homer, the Russians—nothing of note seems to have escaped him. It was this immersion in the most enduring works of imaginative literature that informed his rendering of the Civil War. “The Iliad is the great model for any war book, history or novel,” he said.

Like Homer, Foote focused on two things: the clash of arms and the lives of the warriors. The grand issues of politics and diplomacy, of economics and culture, mattered less to Foote than re-creating the reality of battle. “The idea is to strike fire,” he wrote, “prodding the reader much as combat quickened the pulses of the people at the time.” Critics took Foote to task for this single-minded focus, but he believed in his approach, and stuck to it. “I think the superiority of Southern writers lies in our driving interest in just…two things, the story and the people.” In a way, Foote is one of the little-noted pioneers of the New Journalism, the movement to bring fictional technique to nonfiction subjects, elevating journalism, history, and biography to the level of literature.

He also saw himself working in a broader tradition than that of many mainstream historians. “My hope was that if I wrote well enough about what you would have seen with your own eyes, you yourself would see how those things, the politics and economics, entered in,” he said. “I quite deliberately left those things out. My job was to put it all in perspective, to give it shape. Look at Flaubert: He didn’t criticize Emma Bovary as a terrible woman; he didn’t judge her; he just put down what happened.”

Time has vindicated his view. There are other books about other parts of the war—great books. No other volumes, however, put the reader in the horror and the haze so effectively and so memorably. It was hard but rewarding work. “The battle scenes are lit by a strange, lurid light…. I have never enjoyed writing so much as I do this writing,” he wrote. “It goes dreadful slow; sometimes I feel like I’m trying to bail out the Mississippi with a teacup; but I like it, I like it.” He grew obsessive in his study in Memphis: “All I want is to work at my book, a great wide sea of words.”

He visited the battlefields in season, walking them at the same time of year as the soldiers had walked them. “For one thing, it’s teaching me to love my country—especially the South, but all the rest as well. I’m learning so many things: geography, for instance. I never saw this country before now—the rivers and mountains, the watersheds and valleys.” The books are as much a biography of the land and the elements as they are of the men who fought the war: It is the accumulation of such atmospheric detail that lends the trilogy much of its vivid novelistic feel.

Foote undertook his narrative of what he would later call “the crossroads of our being” in the years in which the civil rights movement forced the South to confront the war’s worst legacy: segregation. He began work in the months after the Brown v. Board of Education decision came down, published his second volume in the year of the March on Washington, and completed the trilogy as the struggles over affirmative action were taking shape.

Foote was no liberal on issues of race, but he was more fair-minded than many of his contemporaries in the South. His admiration of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s military genius, for instance, transcended his sense of outrage at Forrest’s politics, including the general’s involvement in the Ku Klux Klan. To Foote, the Confederacy’s defeat was in a way foreordained, but more for material reasons than moral ones: “You just can’t whip 23,000,000 people with 9,000,000—especially when nearly half of the latter number are slaves.”

Yet Foote knew evil when he saw it. In a bibliographical note composed for the second volume in 1963, he wrote: “I am obligated to the governors of my native state and the adjoining states of Arkansas and Alabama for helping to lessen my sectional bias by reproducing, in their actions during several of the years that went into the writing of this volume, much that was least admirable in the position my forebears occupied when they stood up to Lincoln.” Ross Barnett, Orval Faubus, and George Wallace were fighting battles that should have been settled on the side of justice. “I feel death all in the air in Memphis, and I’m beginning to hate the one thing I really ever loved—the South,” Foote told Percy. In the note at the conclusion of the second volume, he added: “I suppose, or in any case fervently hope, it is true that history never repeats itself, but I know from watching these three gentlemen [Barnett, Faubus, and Wallace] that it can be terrifying in its approximations.”

In the summer of 1973, recuperating from a head cold and fascinated by the Watergate hearings on television, Foote neared the conclusion. “There’s a strange sort of twilight over all this part of the book, a murkiness as if the rebels were slogging along the floor of hell, stomachs all knotted with hunger and knees about unjointed from fatigue.” He told Percy of a small but telling moment on the eve of Appomattox: “Yanks threw down one scarecrow retreater, yelling: ‘Surrender! We got you!’ He dropped his rifle, raised his hands. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘and a hell of a git you got.’ There was never an army so thoroughly whipped, short of annihilation.”

William Faulkner was Foote’s literary idol, and Walker Percy was the friend of his heart, but it was Robert Penn Warren who, with a single telephone call, may have done the most to elevate Foote to his present status as the American bard of war. Ken Burns, a young documentary filmmaker, had told Warren, whom he knew from an earlier work, All the King’s Men, that he was thinking about a project on the Civil War. At dinnertime one evening, Burns’s phone rang, and it was Warren. Warren’s suggestion: You have to talk to Shelby Foote. Thus began an enormously influential collaboration. Burns’s epic PBS film, which debuted in 1990, relied heavily on Foote’s voice. “One of the things about Shelby in our work was how he really became a force field that prevented anyone else—and this is not to take away from any of the great people who worked with us as well—from moving in the same orbit with him,” Burns told me. For Foote, celebrity followed almost instantly. By the time of his death in Memphis in 2005, he was one of the most iconic of American writers.

At the end of the drafting of the third and final volume, in July 1974, twenty years to the season after Foote first went to New York to talk over the project, Walker Percy finished reading the proofs and sat down to write his friend. “Dear Shelby,” he wrote, “Yes, it’s as good as you think. It has a fine understated epic quality, a slow measured period, and a sustained noncommittal, almost laconic, tone of the narrator. I’ve no doubt it will survive; might even be read in the ruins.” It might indeed.

Excerpted from American Homer: Reflections on Shelby Foote and His Classic The Civil War: A Narrative (April; Random House), which is part of a rerelease of Foote’s famous trilogy.