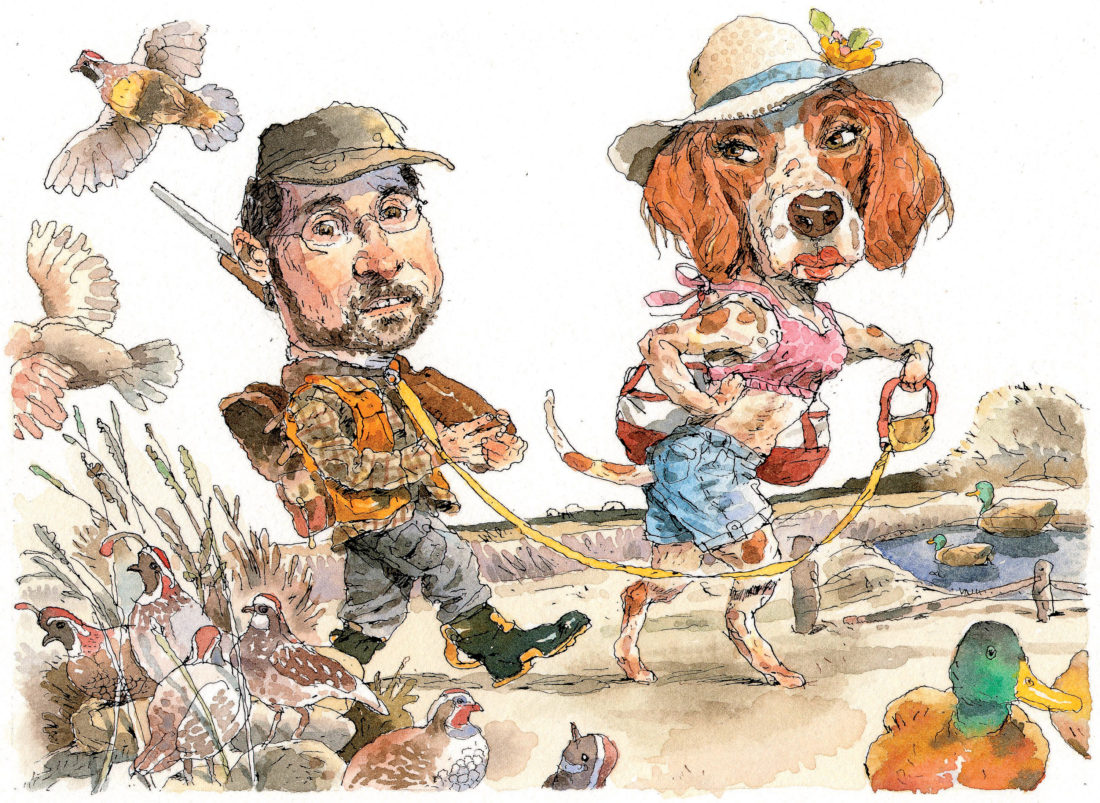

When it came to selecting my first gun dog, I had one rule—and it came from my wife, Idie: “Bring home a female. There’s too much testosterone in this house as is.”

Truth be told, I needed the advice. As the son of an architect and an artist, hunting and guns were not a regular part of my Southern upbringing. When I arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1986 to work with Frank Stitt at Highlands Bar and Grill, I had yet to be exposed to quail hunting and the traditions and passions it inspires. And I certainly had never considered what it meant to own a bird dog.

After a few trips in the fields, I quickly decided that those who owned and trained their own gun dogs were enjoying the apex of the wing-shooting lifestyle. When you see a man and dog in action it’s damn near impossible not to want to experience it for yourself. So in 2001, after sixteen years of following others’ dogs through the woods, I decided to join the gun dog fraternity. Now I just needed to find the right dog.

Over the years I had the privilege of traveling to a number of great hunting camps—not because I am a particularly great shot or a brilliant conversationalist, but rather because I can cook a decent camp meal. During that time, I began to learn what it takes to find, train, work with, and hunt with a gun dog. I was given names of kennels, countless dog-training books, and tons of advice. A whole world of information began to flow from people I had never met but who had heard I was in the market for a puppy, specifically a setter puppy.

But my biggest break came when I ran into Charlie Perry. Perry is an avid outdoorsman and dog owner but also, most importantly for me, a dog swapper—a specialized dog man who curries favor with the best trainers, breeders, and plantation owners in the country in order to have access to puppies. There are lots of these guys out there, some better than others. Perry makes an art of it. For our deal, Perry wanted the right to hunt with the dog when he desired and to have a pick of her first litter.

Perry told me that Mrs. John Harbert, owner of the famous Pinebloom Plantation near Albany, Georgia, owed him a puppy, and asked if I would like to have that dog. Larry Moon had run Pinebloom’s kennel for years and earned a reputation for producing some of the finest bird dogs in the country, many of them regularly winning national field trials. To say your dog comes from Pinebloom gives you instant credibility. It was my shot at the dog of a lifetime. So off I went to South Georgia with the aforementioned set of instructions from my wife—no males.

I met Moon at the kennel, and he took me to see the pups. They were sixteen weeks old and had already started getting exposed to the outside world. When it came to choosing my puppy, there wasn’t really an aha moment. I simply asked about the two females and Moon pointed to the one with “the most hunt in her.” That was all I needed. I named her Sadie, put her in the car, and headed back to Birmingham.

Having read a number of books on training and spoken with every person I knew and respected in the dog training world, I set about the task of first bonding with and then attempting to train Sadie. The daylight hours before my shift in the kitchen were too hot for training sessions. So for the first few months we trained after work, between eleven p.m. and midnight, at a local golf course. There we’d attempt basic yard commands—how to heel, come, and respond to a whistle. Our first night out was pretty telling of our future together. Having gathered my training gear, I made the mistake of cracking the door before clipping the check cord to Sadie’s collar. Away she went. It took me thirty minutes to find her.

At the time, I was forty years old. Having driven my wife, my children, my staff, and a number of my friends half crazy with my overbearing ways and insistence on things being done a certain way, I was ready to settle into less of an alpha personality. But Sadie gladly assumed that role. The first thing you notice in an alpha dog is that it would rather strike off alone than be with you. And when you give a command, it may or may not pay attention, depending on its mood. In many ways, training an alpha dog is not unlike raising teenagers. In the field, an alpha bird dog will follow its nose into the next county, paying little heed to commands to stop. And as you may have guessed, it’s tricky to shoot a quail when your dog goes on point a mile from where you’re standing. Cullom Walker, a dear friend and father figure, once told me, “I don’t hunt dogs, I hunt birds. If the dog doesn’t want to be with us, fine. We have other dogs.”

Eventually, I began to get advice from those that had traveled down the same road I was on. At first they treated me gently, speaking in the third person about someone they’d known who would always yell at his dog, or who would constantly whistle for the dog to come, or who was perhaps a little quick to reprimand her. Then they began to speak directly to me, about me. Yet again, my wife offered sage advice: “Don’t make us duct tape your mouth. Leave the dog alone.” In other words, I needed to shut up and back off. It seems Sadie wasn’t the only one displaying a bit of alpha.

As the years passed, Sadie and I both began to mellow out. She would show signs of affection and would even stick with me on hunts for extended periods of time. After five years, we both realized we didn’t have to fight each other. Sadie is now nine years old, and I am forty-nine. She and I hunt beautifully together. I guess it comes down to this: We understand each other. I afford her an occasional disappearing act, but I now know she will return, or I will find her beyond my range of sight but waiting patiently on point.

Chris Hastings is the owner and executive chef of Hot and Hot Fish Club in Birmingham, Alabama. He now owns three dogs.