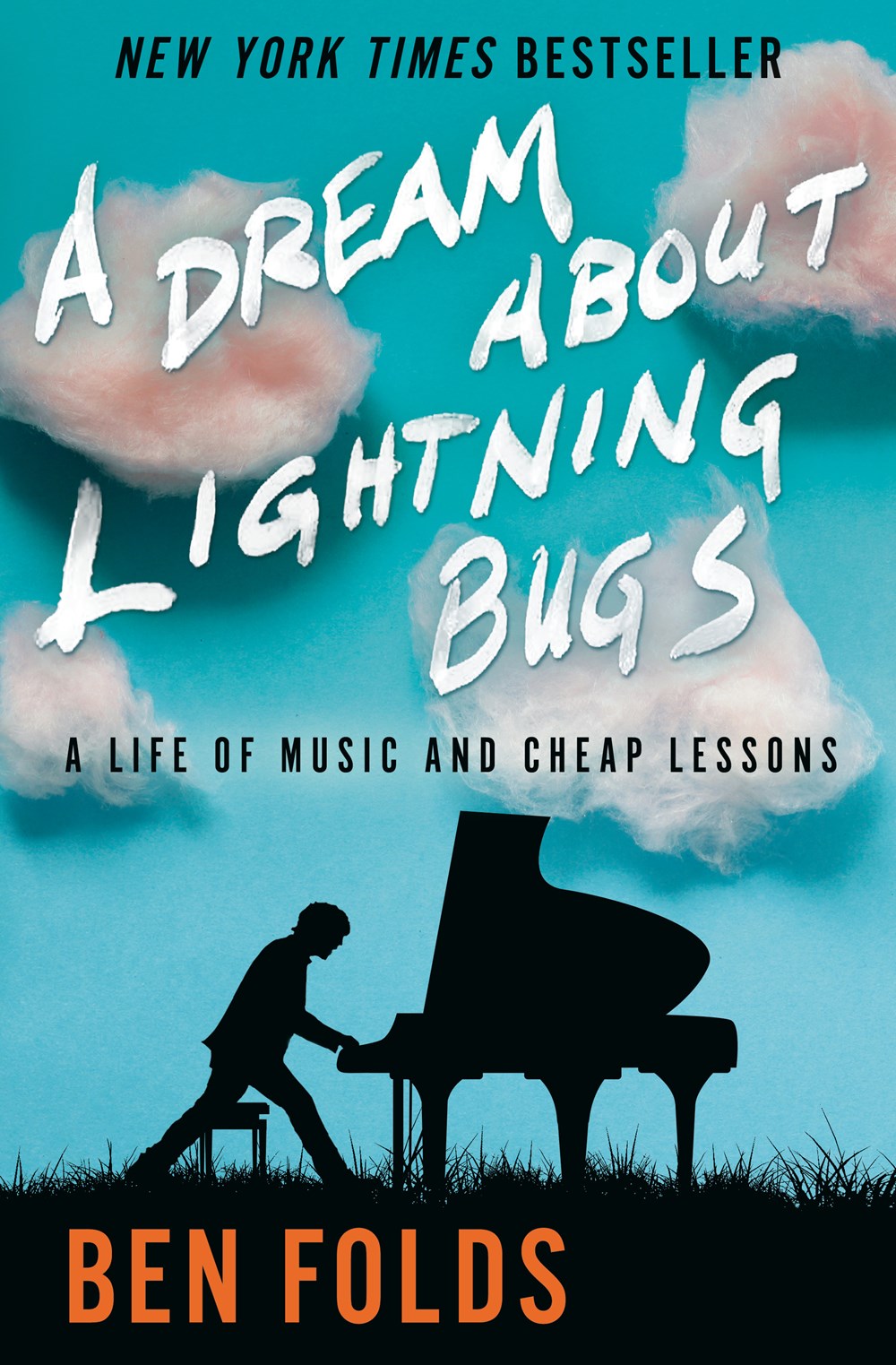

The singer-songwriter Ben Folds is a natural observer. When the piano-playing solo artist and former frontman of Ben Folds Five was growing up in the 1970s, his family moved homes nearly every year in Greensboro and Winston-Salem, North Carolina, flipping houses and following his dad’s contractor work. “My family never traveled geographically outside of North Carolina, but I felt like a world traveler,” Folds writes in his new memoir, A Dream About Lightning Bugs. “It can be a little lonely, but such is the perspective of a songwriter, and this kind of upbringing was excellent training ground.”

In this artful and entertaining book, marked by salty language and irreverent, charming takes on his own life’s stumbles, Folds shares the lessons he learned growing up in the South and pursuing the life of a musician, as well as the stories behind such beloved songs as “Brick,” “Rockin’ the Suburbs,” and “The Luckiest.” We spoke with Folds about A Dream About Lightning Bugs, his observations of the complicated South, and his advice for those who chase their creative dreams.

What’s the story behind the book’s title?

A dream from when I was really teeny has stuck with me. I was in the backyard at home in Greensboro, North Carolina, with lots of other kids and I was seeing lightning bugs light up, but none of the other kids could see them. I would point them out, and then the other kids could see them. Kids were following me around because I was the man and I knew where the lightning bugs were. Then I would bottle them up and hand them out—I was like the lightning bug guy.

Years later, as I thought about the way that image had stuck with me, it seemed to be a metaphor for creating. Real creation is taking something that’s there in front of you, that’s interesting to you and bottling it, framing it in a way you can share. It’s true of any creative endeavor from cutting hair to architecture. I can’t see architectural space, but I can hear a car horn or a washing machine, and I’ve got a song.

In the book, you write about the in-between moments of life and the pauses in your creative process, and how scary those blank spaces can be.

Everyone can understand the feeling of having just breathed out…and you haven’t taken the next breath. Or a tide coming in: Right at that space before a wave goes out, there’s this floating moment. It feels like that in life sometimes, to have no idea what’s next. Those times should probably be seen as exciting because something new is coming along and you don’t know what it is. But it’s also really hard to get excited about those moments because you fear for the worst. Like, Oh shit, I’m not going to have a job. Or I’m not going to ever think of another song again. I put that stuff in the book from my own life because I could have used someone telling me then, No, this is good. No seriously, calm down, it’s going to be okay.

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Folds

Folds in 2000 during the recording of Rockin’ the Suburbs, waiting for edits.

Was writing the book at all like songwriting?

It was very similar in some ways. You think you have more real estate than you do. At first I thought, Oh I can write long and say whatever I want, but the truth is you don’t need fat in anything you write. In a song, the constraints are incredible; there’s a whole obstacle course to get through to share characters and syllables and get your point across. But the fun of writing a song is finding opportunities within the restrictions—you find ways to say things you would have never thought to say, and it ends up being a bit like a crossword puzzle.

That exists on a much broader scale when writing a book. You still have to be economical. You have to say what’s true—or what’s true to the arc of the story—and you have to organize it in such a way that pulls you along. I chose short chapters that toss the ball to the next. I treated them like little mini verses. It wasn’t ghostwritten at all. And working with an editor was a bit like having a producer in the studio.

You write about how you were a sort of weirdo artist kid growing up around Winston-Salem. Did you know you were weird at the time?

I didn’t really feel like I was in the club, and growing up, you want to be in the club. I think most people have felt that way before, like I’m not really part of this. One day I might be at a friend’s house who was utterly dirt poor, and then the next day at the CEO of so-and-so corporation’s house and climbing into a helicopter. I was up and down that scale constantly. But when you’re not any of those people, what you notice is the way you don’t fit, and you don’t ever feel completely immersed. It’s like being on the sidelines at the high school dance. But the good thing is you see things. You observe. I don’t know if I realized that at the time, but observation became a part of who I am.

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Folds

Ben Folds practicing piano in 1984. In the background, an original painting of a piano player by his mother, Scotty Folds, hangs on the wall.

The South inspired some of your songs—like that line in “Jackson Cannery” that goes Millionaires and mill rats live side by side.

There was a very strong lower working class in Winston-Salem, and then old, old money. Not to be confused with rich. We’re talking about more of that Southern, genteel old money, living in an antebellum house, not putting the expensive car out front. They have influence, they have knowledge, they have access. A lot of people go oh rich, thinking about a big house and a shiny car, but understanding the difference between “rich” and “old money” is what leads me to write a song like “Rockin’ the Suburbs,” which is about middle-class anger. I never wanted to make much of that song, it was kind of a joke, but I remember hanging out with kids in some McMansion and they wanted to throw something through a window. I was like, But you’ve got nice stuff here at home, why don’t we go play video games? Why do we gotta break shit?

You’ve also lived in Nashville and Franklin, Tennessee. What advice do you have for someone visiting the South, who might be unfamiliar with its complexity?

There are so many Souths. When you go into some place for a little while, you’re just not going to get it all. Hopefully anywhere you visit you can visit someone at home, not just stay at a hotel and stop by the great barbecue place someone mentioned. Being in someone’s home is a way to understand a place. There is always more to people than what meets the eye.

A Dream About Lightning Bugs is both a memoir and a guide to the creative life. What do you hope people take away from the book?

This is a clear view of one person and what made them a professional artist—how that works with living a life. Since everyone’s different, making it a how-to would be very irresponsible and like the worst parts of Ted-Talk-world. I would prefer to just offer my services by giving an entertaining account of what I got out of this artist life. If someone doesn’t agree with the way I handled a situation, they know not to take the advice.

As a kid, I noticed there was no real access to rock stars behind their rock star façade. I would have liked to have known how Gene Simmons knows what keys his songs are in. How did he learn that? Did he play scales? Did he fail? What did he do before he figured out the makeup thing? I would have liked to know that as a kid.

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Folds

Folds, in eighth grade, playing drums in the Wiley Junior High Jazz Band in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Another thing with this book: I often feel that successful professional artists don’t regard amateur artists—the ones who don’t make a living at it—as equals. And I think that we should because we’re all creating stuff. Most artists do other things. They have to make a living. Toward the end of the book I point out how Charles Ives, who was one of our most important composers of the early twentieth century, was an insurance salesman—and so he had the opportunity to write music without having to conform. In our very celebrity-saturated culture now, it’s easy to feel bad or almost embarrassed if you do something on the side. Like, Well, I do my little art thing. It’s not a little art thing! You’re doing it.