More than nine million barrels of spirits are currently aging in Kentucky, and not surprisingly, most of them contain bourbon whiskey. That’s roughly two barrels for every person living in the state, and enough, distillers hope, to keep pace with a growing global thirst for America’s native spirit. As a born-and-bred Kentuckian, I’ve consumed my fair share. However, I’m stumped as I study the list at Doc’s Bourbon Room, which opened this year in downtown Louisville. A back bar filled with gleaming amber-liquid-filled bottles is table stakes these days, especially in Kentucky, but Doc’s is all in on its bid to offer the world’s largest whiskey selection. More than three thousand bottles fill every wall, with library ladders and a Dewey-decimal-like numbering system.

I decide on a pour of fourteen-year-old King of Kentucky. Spirits giant Brown-Forman resurrected the historic brand in 2018 as a high-end single-barrel bourbon, with an only-in-Kentucky release of fewer than a thousand bottles and a suggested retail price of $199. Where else am I going to try a taste? We are living in a time of peak bourbon, when whiskey isn’t just an adult beverage—it’s a lifestyle. And one worthy of an adventure, as my wife and I found on a recent road trip through Kentucky in search of the best of the bourbon renaissance.

Beginning in Louisville, heading to the countryside in Bardstown and Harrodsburg, and wrapping up in my hometown of Lexington, I wanted to see how the bourbon boom has fueled a building boom. The Kentucky Distillers’ Association reports that more than $2.3 billion in capital projects have been completed or are planned over the next five years here. Distilleries are expanding their visitors’ centers and adding restaurants and bars to welcome the whiskey pilgrims who make nearly two million stops along either the Kentucky Bourbon Trail or the Kentucky Bourbon Trail Craft Tour each year.

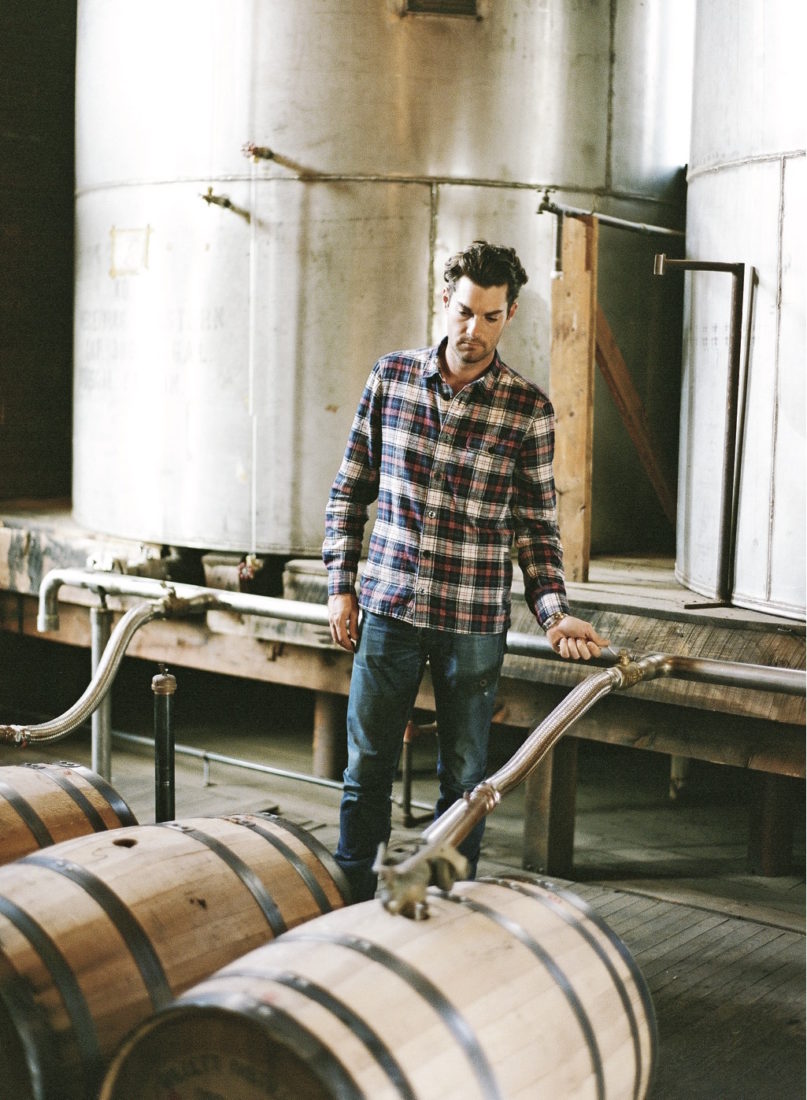

Not long ago, Louisville billed itself as the Gateway to Bourbon Country. It has since pivoted to the unofficial moniker Bourbon City as bourbon-related businesses have cropped up downtown, many of them near a block-long stretch of Main Street known as Whiskey Row. Our first stop is Angel’s Envy, which opened a sleek new distillery just east of Whiskey Row across from Slugger Field in 2016, becoming the first full-production distillery in downtown Louisville since Prohibition. Smaller distillers—including Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co., Copper & Kings American Brandy Co., and Rabbit Hole Distillery—have since joined. “First and foremost, we have to make whiskey,” says Angel’s Envy cofounder Wes Henderson. “But we wanted to build the facility in a way that was very friendly for fans of the brand.” After a review of some bourbon essentials from our tour guide (distilled in the United States from a mash made with at least 51 percent corn; aged in a new charred-oak container), we take a dive into why distillers here give whiskeys a second soak in used port or rum barrels, before we sample a taste straight from the cask.

Next we head to Whiskey Row and Old Forester, where we dip our fingers in fermentation tanks filled with bubbling sour mash, watch as coopers build and char barrels, see new-make whiskey running through a forty-four-foot-tall copper still, and smell the angel’s share in the aging warehouse. While Old Forester uses the same mash bill, or recipe, for all of its bourbons, master taster Jackie Zykan says each barrel uniquely influences the liquid inside as it ages. Zykan and her team taste through each batch to identify barrels that might be bottled on their own as a single-barrel bourbon, or blended to fit within a desired flavor profile. “We’ve got spicy ones, we’ve got fruity ones, we’ve got sweet ones,” she says. “There are two hundred or so different aromatic compounds in a glass of bourbon, so there’s plenty to play with.”

For predinner drinks, we walk along Main Street to Michter’s Fort Nelson Distillery and its cozy second-floor lounge, which offers a strong cocktail menu split between classics curated by drinks historian David Wondrich and modern twists dreamed up by the bartenders. We explore bourbon’s pairing possibilities during dinner at Butchertown Grocery, an upscale bistro east of Whiskey Row. I’m skeptical of the pear salad topped with a dollop of jalapeño blue cheese ice cream and studded with candied pecans, but the accompanying pour of Michter’s US1 American Whiskey bridges the sweet and savory contrasts. Likewise, a splash of Shenk’s Homestead Sour Mash Whiskey tames the snap of ground bourbon-barrel-aged peppercorns atop creamy bucatini pasta.

Back on Whiskey Row, we check into the newly opened Hotel Distil, which interprets the bourbon lifestyle with a clubby feel I can only describe as akin to a buttery-soft leather armchair. Opt for a Connoisseur Suite for a well-stocked bourbon cart and access to a whiskey steward who will come to your room and mix drinks.

While Louisville is awash in more ways than ever to take a bourbon plunge, one must venture into the countryside to truly get into the spirit. Drive the back roads. Put on some Tyler Childers. Roll down the windows. We’re doing just that as we wind along a not-quite two-lane on the way to Maker’s Mark Distillery in Loretto. I crest a hill and see the campus below, its black-painted buildings trimmed with iconic red accents. Tufts of steam rise from the distillery’s roof. A red-tailed hawk circles overhead.

Even here, where distillers have been making bourbon since 1805, there is room for experimentation. The most visible example is a massive temperature-controlled, limestone-walled cellar built into a hillside and used to age barrels of Maker’s Mark 46 and the company’s Private Select line. Those bourbons begin life as cask-strength Maker’s Mark before the addition of seared French and American oak staves that can be combined in different ways to enhance the whiskey’s complexity.

Bardstown Bourbon Company, about fifteen miles north, is also pushing bourbon boundaries. Master distiller Steve Nally (previously a longtime master distiller at Maker’s Mark) oversees a state-of-the-art system that controls several hundred ways to nip and tuck the production process. Distillers here make whiskey for the company’s own products, as well as customized recipes for more than two dozen contract customers. It’s a far cry from when Nally started in the industry forty-eight years ago. “Basically, the only things that we controlled then were acid, pH, and gravity,” he says. “Now it’s everything from the grind profile to the temperature of the cook, the temperature of the condensers, and all five hundred of the different points that we monitor.”

The glass-walled distillery is also home to the Kitchen & Bar, which has become one of the most popular restaurants in town, as has the Bar at Willett, newly opened on the grounds of the nearby Willett Distillery. “Bardstown, let’s be honest, isn’t really a food destination,” says Willett master distiller Drew Kulsveen, a fifth-generation distiller and a semifinalist for a 2020 James Beard Award. “So hopefully this is more of an attraction for people who want to come here not just for bourbon, but also for food and cocktails.”

I enjoy a front-row seat as Willett barkeep Jeffrey Knott mixes a whiskey sour. He pours liquid nitrogen into a coupe, sending plumes cascading over the brass-topped bar. He adds bourbon, lemon juice, simple syrup, and egg white to a cocktail shaker for a dry shake and then drops in a cube of crystal-clear ice made from spring water on the property, and gives another hard shake. Discarding the liquid nitrogen, he strains the drink into the glass and uses a stencil and an atomizer to dust the top with a stylized W. The cocktail proves to be an ideal complement to the best corned beef hash I’ve ever tasted.

We arrive in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, an hour east, with just enough time to settle into the century-old Beaumont Inn before a tasting with fifth-generation innkeeper Dixon Dedman. A master blender, Dedman also revived his great-great-grandfather’s whiskey brand, Kentucky Owl, and when available, he’s happy to put together a tasting for guests. An affable host, Dedman likes to meet people where they are on their bourbon journey. “I don’t ever say, ‘Okay, you’re going to get notes of caramelized wolfberry and hints of toasted sassafras,’ or whatever,” he says, as we start in on a flight that includes vintage Old Grand-Dad, 15-year Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve, and barrel-proof Elijah Craig Small Batch. “I prefer to tell people up front that this is an ‘I like it, I don’t like it’ kind of tasting.” As we sip, Dedman encourages me to focus on the sensation the bourbon has on my palate. He explains how rye and wheat, the two most common grains in bourbon after corn, each creates a distinct sensation—rye toward the back of the tongue and wheat on the front.

Sampling brands side by side helps a person zero in on what they like best, Dedman says, as does giving yourself permission to not take whiskey too seriously. “When people come to Kentucky, a lot of times they’re worried that they’re not going to be able to articulate all these tasting notes or say the right things. The best way to drink bourbon is with the people you want to be around. If that means Styrofoam cups in a parking lot with some of your buddies, then that’s what it means.”

I think about this sentiment the following evening back in Lexington, while sipping a Manhattan and sitting across from my wife at Distilled, one of our favorite restaurants. I have fond memories of drinking bourbon with friends around a campfire or with my wife on our front porch in the last light of day. I think what I appreciate the most about bourbon is that it causes a person to slow down and savor where they are and who they’re with. To take life in sips, rather than in gulps.

Like Louisville, Lexington has grown along with the bourbon boom. Beginning with Woodford Reserve, which opened in 1996 just across the county line in Versailles, several distilleries here have revived historic sites from desolation. The owners of Castle & Key spent millions turning the derelict Old Taylor Distillery in nearby Millville into a showplace. The James E. Pepper Distilling Co., now the anchor of Lexington’s thriving Distillery District, brought the brand back to its former home, which had been abandoned for half a century. The sleepy downtown I knew growing up now teems with nightlife. Standouts among the bourbon-centric bars and restaurants include West Main Crafting Co., where the cocktail menu looks and reads more like a coffee-table book, and Lockbox, the stylishly austere bar and restaurant located in the art-accented 21c Museum Hotel.

My wife and I walk the few blocks to Lockbox for an after-dinner cocktail—a Clearance, Clarence for me, made with milk-clarified bourbon, and an old-fashioned for her. We run into friends at the bar, one drink turns into two, and soon we’re dancing to a band upstairs. It’s been a long journey, but we’re in no rush to go home.

This article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.