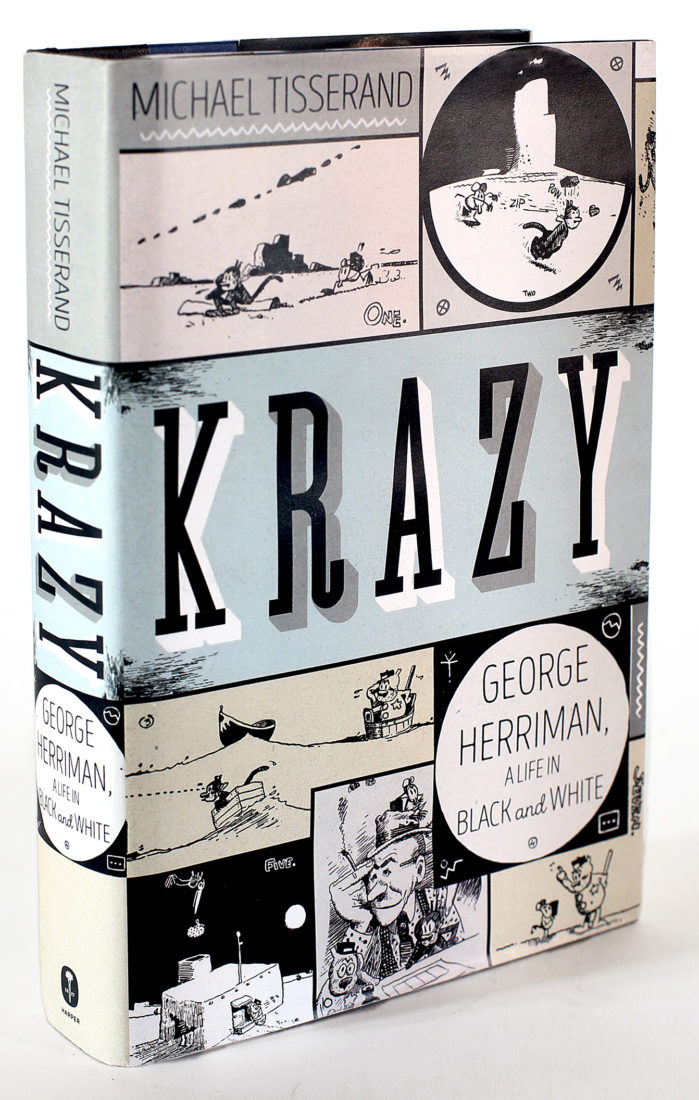

Before “The Far Side,” “Calvin and Hobbes,” or even Mickey Mouse, one cartoon stole the show. From 1913 to 1944, a panel called “Krazy Kat” ran in newspapers across the country and counted “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz and the poet E.E. Cummings among its fans. The strip featured beautiful backgrounds and simply sketched cat and mouse characters that switched between philosophical dialog and slapstick situations—the mouse was forever trying to hit the cat with a brick. But the New Orleans-born artist behind the drawings, George Herriman, was a private man whose life was a mystery. That is until now, with the release of the illustrator’s biography, Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White.

Author Michael Tisserand (also a New Orleanian) spent ten years researching this thorough work that chronicles not only the career of the twentieth century Southern artist, but Herriman’s big secret: He was born to a prominent Creole family in New Orleans and spent his adult years “passing” for white at the newspapers where he worked in New York and Los Angeles. At the time, living as a black man would have threatened his livelihood, his home, and his relationships. We spoke with Tisserand about Herriman’s complicated story and what it means to honor the artist’s legacy today.

How did you get interested in “Krazy Kat”?

I loved comics as a kid, and I would ask my mom to drop me off at the library so I could read them. Fast forward to when I was the editor at the alternative weekly paper in New Orleans. I knew that Herriman was a native of New Orleans and I thought he would make a good piece for Gambit. I was working on it when Katrina hit, and I relocated to Chicago. There was an exhibit on the masters of American comics, and one room was all Herriman originals. I started reading “Krazy Kat” aloud and I was just spellbound. I was feeling like a New Orleans exile at the time, and here was the chance to write about another New Orleans exile.

For people who aren’t familiar with “Krazy Kat,” can you describe the cartoon?

Herriman was a cartoonist’s cartoonist and it was popular among intellectuals and artists. The star is a cat who was both male and female and neither or both, who would often change colors from black to white. Sometimes these color changes were justified by a slapstick convention, sometimes by a dream, and sometimes it just happened. When Krazy talks, it comes out as this wonderful American invention that’s a combination of Elizabethan English, Creole, Yiddish, German, or Spanish all melded together in one seamless, expressive dialog. And there is Ignatz, a mouse who has an obsession with throwing a brick. He’s drawn as a simple doodle, a body and a couple of mouse ears. But these simple characters are placed on wondrously drawn backgrounds. Herriman would approach the page like a brand new canvas. It was not a usual strip, and in it, Herriman was expressing what I believe are deeply personal and not easy-to-communicate feelings about his own identity.

Photo: Courtesy <i>Krazy</i>

A panel from “Krazy Kat.”

What did you learn about his identity?

He was born to free people of color in New Orleans [in 1880]. His family prized education, and the reason they left New Orleans was schools were closing to Creoles and people of color. So they moved to Los Angeles and “passed” as white. The complications of identity were known very clearly by Herriman throughout his career. On one hand, he was living and working as a white man. But there was a racial covenant on the home that he owned. The bank could have taken his property. And there were stories in the newspapers where he worked of people whose race was “discovered.” Herriman was one headline away from that kind of fate.

How did he address his background in his work?

All kinds of ways. In one comic, there is a black guy impersonating other ethnicities so he could go play music, until people find out who he is and beat him up. It’s hard to overstate how beloved Herriman was among his peers—his work was so highly respected—but his colleagues at the newspapers would joke about his identity constantly. “George the Greek” became his nickname. It was clearly kind of a “don’t-ask-don’t-tell” situation.

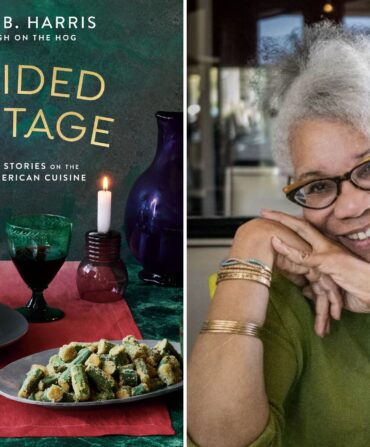

Photo: Courtesy Dee Cox

George Herriman c. 1922.

How do you think he’d feel today about you “exposing” him?

I wonder if he’d be mad at me. I’ve asked myself that. I don’t know how Herriman would work in 2016—all we have is his work in the 1900s. Lots of people came through New Orleans and went through the experience of racial passing, but only Herriman created “Krazy Kat.” My hope is that by telling his story as accurately as possible, it lights up sections of his work that might have been obscured before.

It’s so easy to limit our conversation to the latest headline, but in reading “Krazy Kat,” you see that this crazy, multi-layered, rough-hewn American identity has been forged through very difficult times by some very visionary artists.

Photo: Courtesy <i>Krazy</i>

A 1922 self-portrait by George Herriman.

What should George Herriman’s legacy be today?

I see his legacy as someone who was able to create with wonder and a sense of delight a strip that reflected many of America’s darkest moments. As an artist, he brought joy onto the page even when he was creating a work that had a deep undercurrent of sorrow. And as a writer, he was incapable of compromising his vision. He could not have done anything else—he had to create this work that he fully inhabited and that fully inhabited him.