North Carolinian Linda Shropshire first found her love for the arts in her seventh-grade classroom when her art teacher, Winston Fletcher, introduced her to historical painters—including those often excluded from the spotlight. “He taught me about Rembrandt, Picasso, Elizabeth Catlett, Edmonia Lewis, and Ernie Barnes,” she says. In her twenties, Shropshire began building her personal collection after she bought her first work from the South Carolina artist Floyd Gordon, paying it off through a nine-month payment plan. “I couldn’t afford it,” she says. “But I fell in love with it.”

Shropshire dreamed of opening her own art gallery, one that was inviting to all, in Durham, where she planted her roots in 1996 after growing up in Charlotte. Accessibility—for both viewers and creators—fueled her vision for a space that focused on a diverse canon encompassing more women and creatives of color. Serving on the board of trustees at the North Carolina Museum of Art and the Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums exposed the gap of Black Southern artists in the collections, exhibits, and leadership positions in large institutions. Shropshire’s mission was close to her heart: “As a Black woman, I’m at the cross section,” she says. “I can see things from a different perspective and show artists and stories that help shape our own narratives, rather than others determining what [Black experiences] are.”

When an opportunity to lease a space on Durham’s Parrish Street, a historic hub for Black entrepreneurs and businesses, landed in Shropshire’s hands, it felt like fate. For Ella West Gallery (named for Shropshire’s mother), she renovated the 1,200-square-foot space in early 2023. The history of the building connects to the past: It housed the printers of the Black newspaper The Durham Reformer and neighbored thriving Black insurance companies, banks, and shops in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When W. E. B. Dubois visited Durham in 1912, the buzzing life and success of Parrish Street captured his admiration, and he even published his own ode to the city in his essay The Upbuilding of Black Durham. For Dubois, Durham’s Black Wall Street, as well as its universities and academic leaders, offered a “solution” to racial inequality, and it set an example for social and economic success for communities across, and beyond, the South.

Shropshire is well aware that being part of Parrish Street means being part of rejuvenating this rich legacy. “I can’t open a gallery without paying homage to those before me,” she says. She had long conversations with leaders of the city, hoping to draw more people to Durham as a destination to appreciate Southern art and life. “We need more spaces for Black artists in the South; there’s a void,” she says. “I wanted Ella West to anchor the culture of Parrish Street. There’s something beautiful about being a Black-owned business on this street and being able to look back and tell that story.”

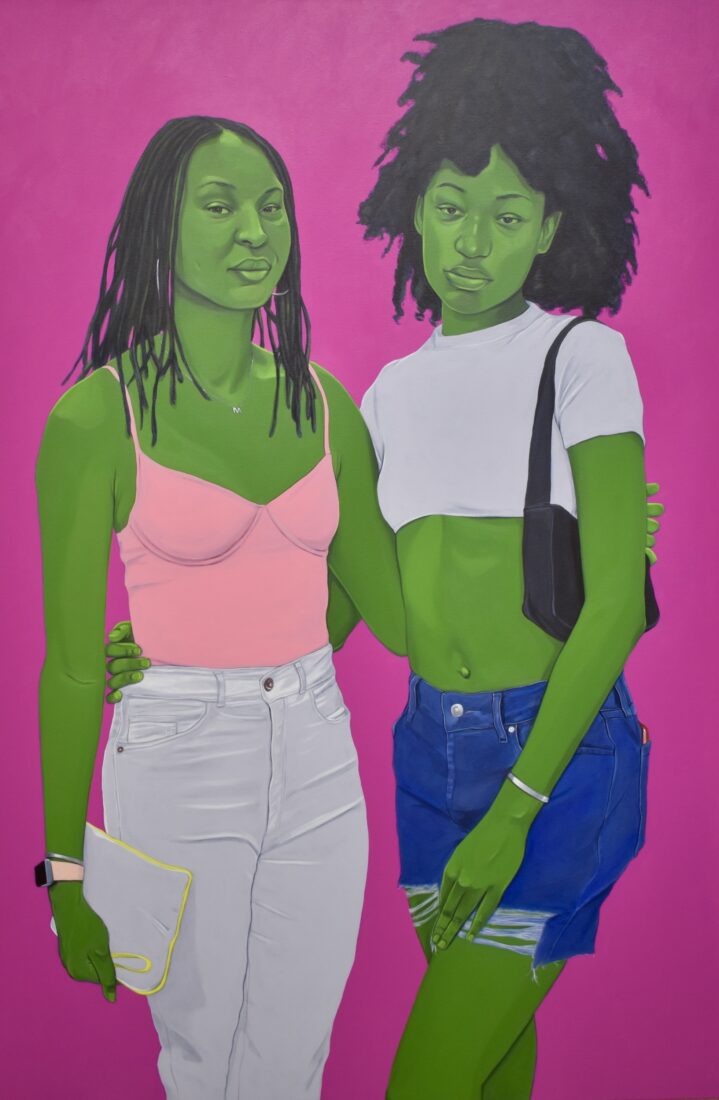

The Ella West Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, Return to Parrish Street: A Dream Realized, debuts August 19 and features four internationally acclaimed artists with roots in North Carolina. Named after Langston Hughes’s poems A Dream Deferred and The Dream Keeper, the exhibition explores themes of dreams, identity, and vulnerability with works from painter Clarence Heyward, photographer Kennedi Carter, multimedia artist Ransome, and painter Ernie Barnes. When visitors first walk into the space, they’ll encounter black-and-white artwork, including a striking monochromatic portrait of George Floyd by Heyward, before the exhibition gives way to full color. Shropshire hopes visitors will sit with the works, even when they feel uneasy—a reaction she finds essential in any art space. “The biggest obstacle is making sure that we make space for things that make us feel uncomfortable,” she says. “Art is supposed to provoke us and challenge our preconceived notions about life, people, places, cultures. Without art we lose this opportunity to inform humanity.”

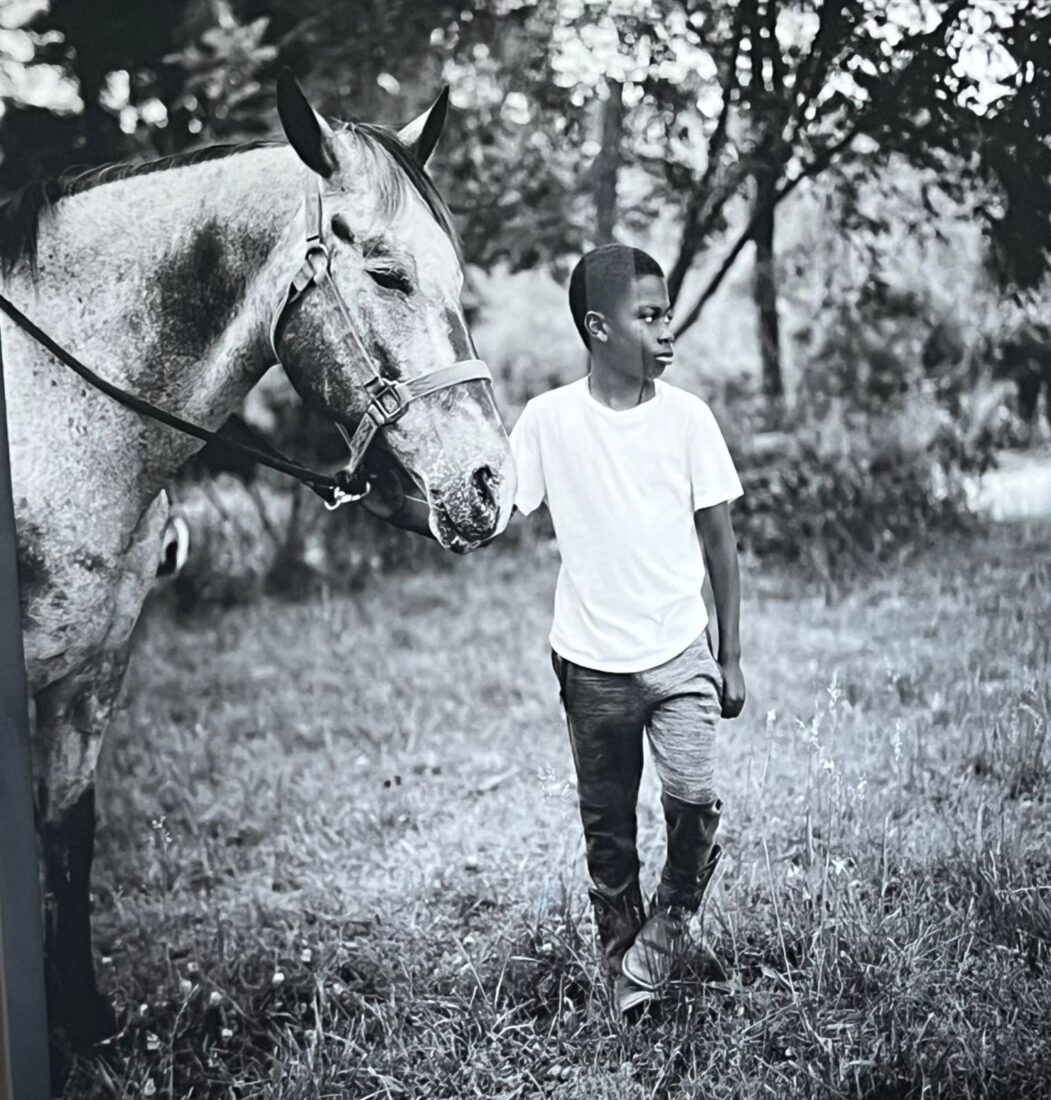

The show balances pain and grief alongside joy and stillness; many of the works in Return to Parrish Street offer quiet comfort and kinship between mothers and daughters, girls and boys. “Kids get to have a chance to be who they want to be without all of the burdens of past generations—and they can just be kids,” Shropshire says of this theme. In Little Girl, a photograph by Carter, soft sheets frame a girl in a cotton dress, whose peaceful face and closed eyes are lifted toward the sun—a quick moment of serenity frozen in a snapshot. In another image, Untitled, a boy relaxes by his horse. Despite the giant size of the animal, the photo encapsulates a feeling of serenity, the comfort that comes with a bond of trust and confidence. The two images manifest, for Shropshire, a dream realized—and a hopeful future to come for the only Black woman–owned gallery currently in the Triangle. “I tell everyone I encounter, I’m doing this for us.”