Of the many things the singer-songwriter Jim Croce left to his two-year-old son after he died in a plane crash in 1973 at age thirty, a collection of a thousand or so vinyl records loomed large. For young A. J. Croce, listening to these old hits—by Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Ray Charles, and the like—steered the trajectory of his life, instilling in him a love of music, inspiring his career, and connecting him to his hitmaking dad forever.

“My father’s record collection was a huge influence on me,” says Croce, a self-taught piano virtuoso and a Billboard-charting singer-songwriter himself, who has collaborated with such luminaries as Willie Nelson, B.B. King, and John Oates. “It was so deep—old blues, jazz, rock and roll, soul, country, folk. Just all over the map.” When he was fifteen, though, a fire destroyed his house, and the collection he’d spent his adolescence augmenting and emulating was lost. Only two albums survived, a little smoke-damaged but functional: a Bessie Smith record and a Fats Waller collection.

Croce has spent the intervening decades rebuilding. Today, at his home in East Nashville, the assemblage stands around four thousand strong, though it’s always in flux. “I’ll go through and pull things out I haven’t listened to in a long time and give them away to friends,” he says. “And I still buy new ones.” He favors a local record store, the Groove, but he also makes time to pop into shops across the world while on tour, unearthing rare 78s from Carolina Soul in Durham, North Carolina, or British rock band 45s with the lyrics charmingly mistranslated in Japan.

To Croce, songs simply sound better on vinyl, which is why he has pushed to press his own music—as well as his father’s (hits like “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,” “Operator,” and “Time in a Bottle”)—on high-quality vinyl, and why he especially values listening to the soundtrack of his early childhood in its original form. “When older music gets mixed as MP3s, you lose the mystery and beauty of the original tracks,” he says. “You want to hear the mistakes; mistakes are human and what make music soulful.” Here are six of the records that have influenced him most.

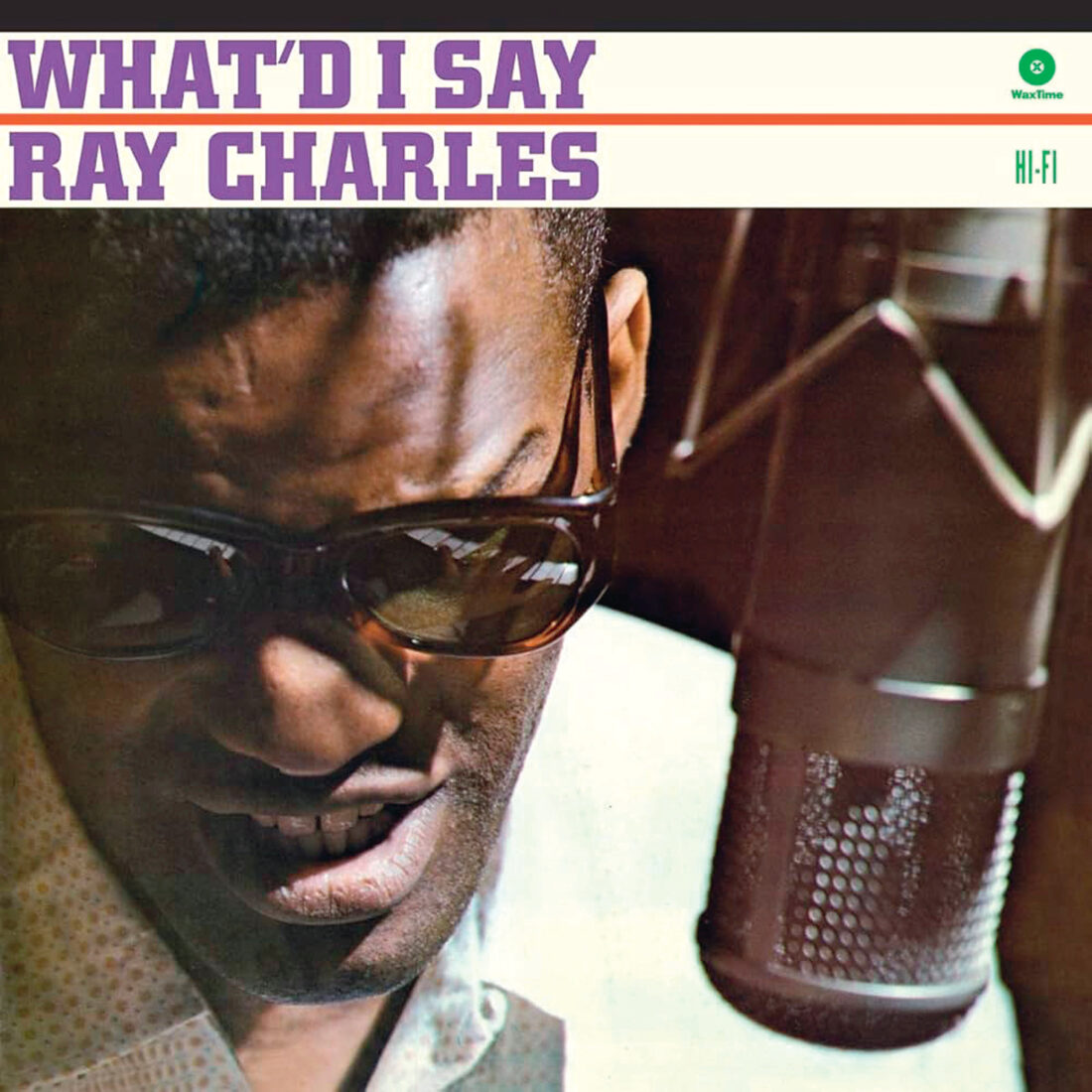

What’d I Say (1959)

Ray Charles

“This is the album that really changed my life. When I was a kid, I lost my sight for a time and was turned on to Ray Charles’s music by family friends. Plus, he was a big part of my dad’s record collection. I was hooked immediately. It was so moving—and fun.”

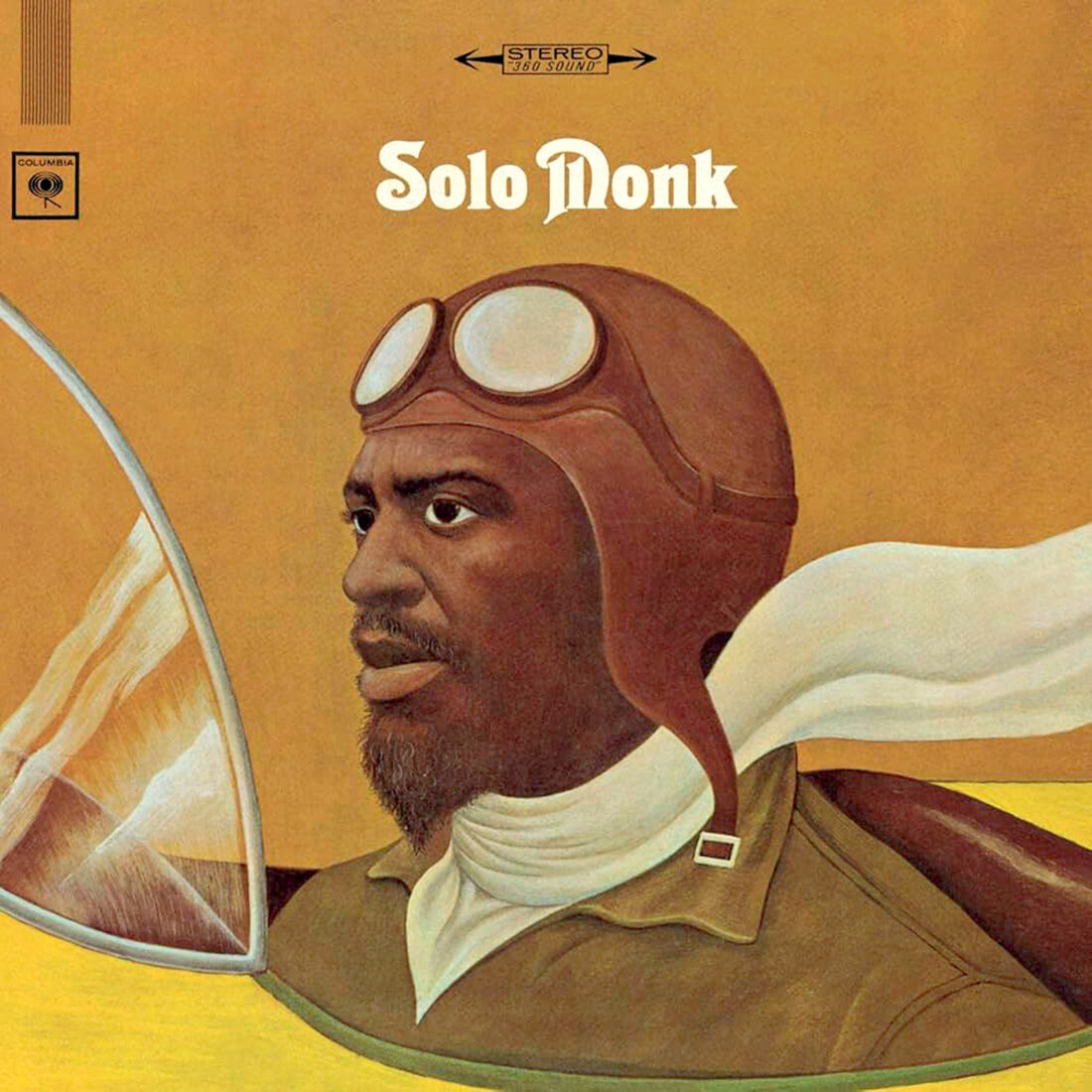

Solo Monk (1965)

Thelonious Monk

“This is like a meditation for me. I don’t want to hear Thelonious Monk play with a band. I don’t want to hear him backing Miles. As wonderful as the players may be that he’s playing with, he’s so uniquely brilliant by himself that for me, it’s like an education every time I listen.”

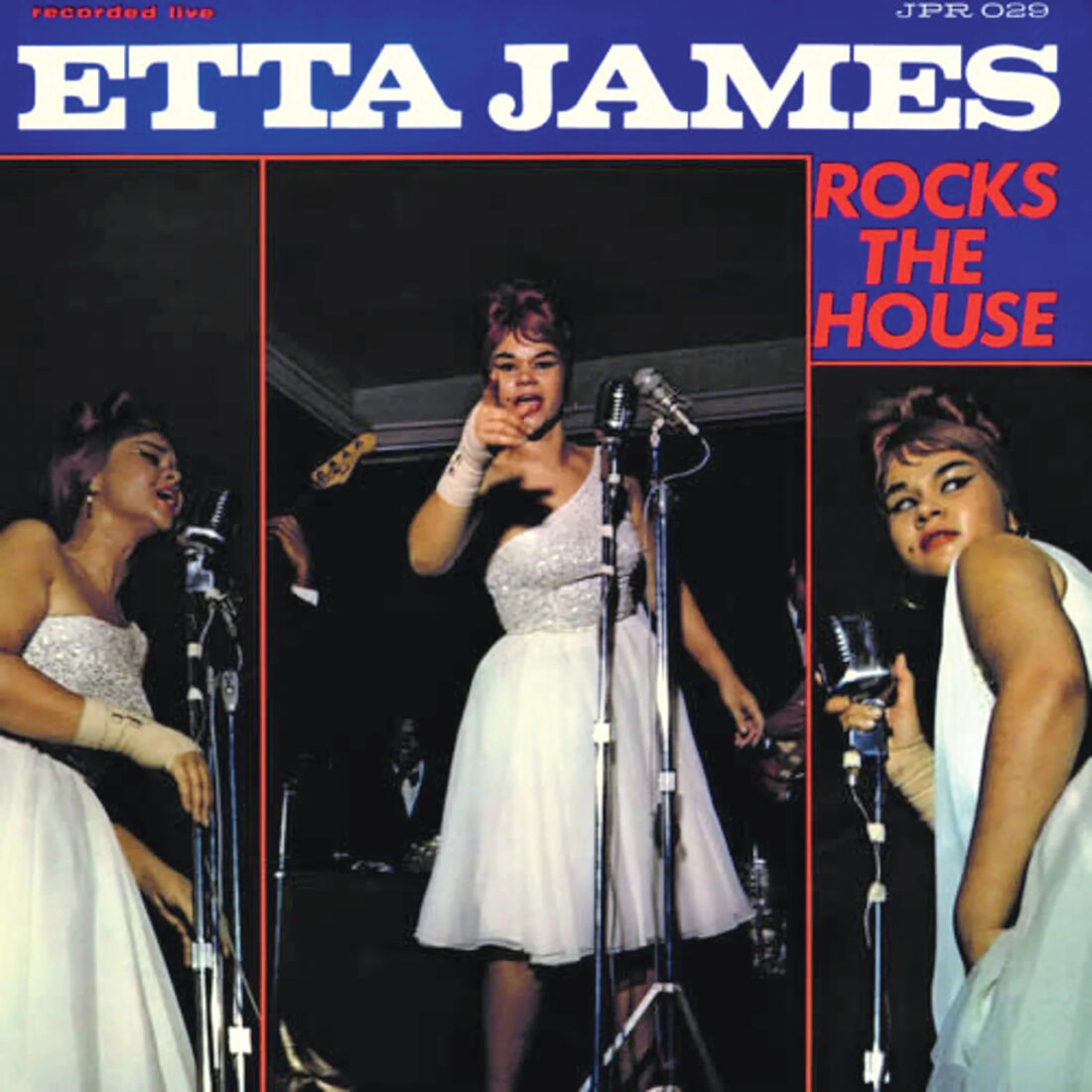

Etta James Rocks the House (1964)

Etta James

“When I was a teenager, I got really into R&B and that sixties English sound as much as I was into jazz and soul and blues. There were all these garage bands in the mid- to late sixties that were all covering R&B. They were all covering the songs Johnny Otis wrote for Etta James, and so in the eighties, when I was part of some bands that were covering music in that style and playing a Vox Continental [organ], this record was hugely influential.”

Jack the Ripper (1963)

Link Wray

“This was a reckless, kind of punk rock album. It was so different than anything else. There were all these wonderful guitar players and bad-ass jazz musicians around this time, but that really wasn’t in Wray’s vernacular. He thought differently, heard music differently, and wanted to sound different than anyone else. So he poked holes in his amplifier, tried things in a unique way. That was really powerful.”

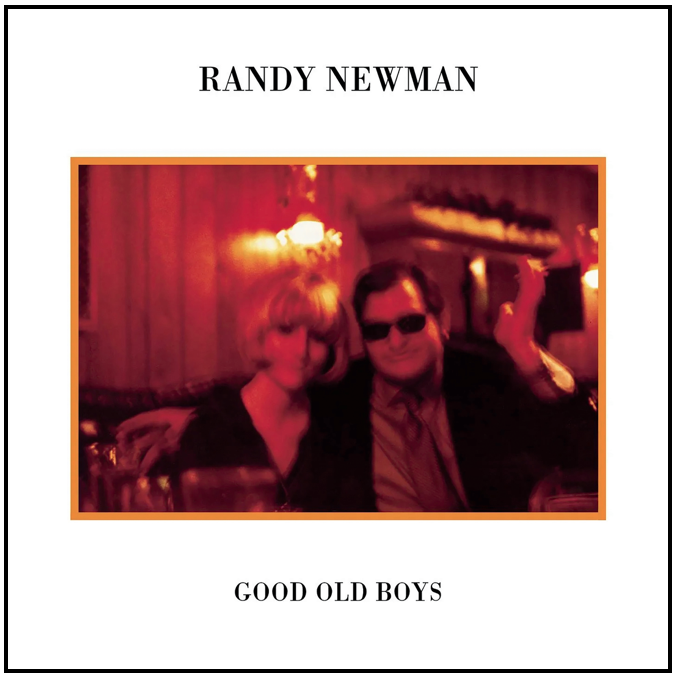

Good Old Boys (1974)

Randy Newman

“The first concert I ever went to as an infant with my dad was to see Randy Newman. I’ve always thought the world of his songwriting—especially in those first few records. And Good Old Boys is a masterpiece.”

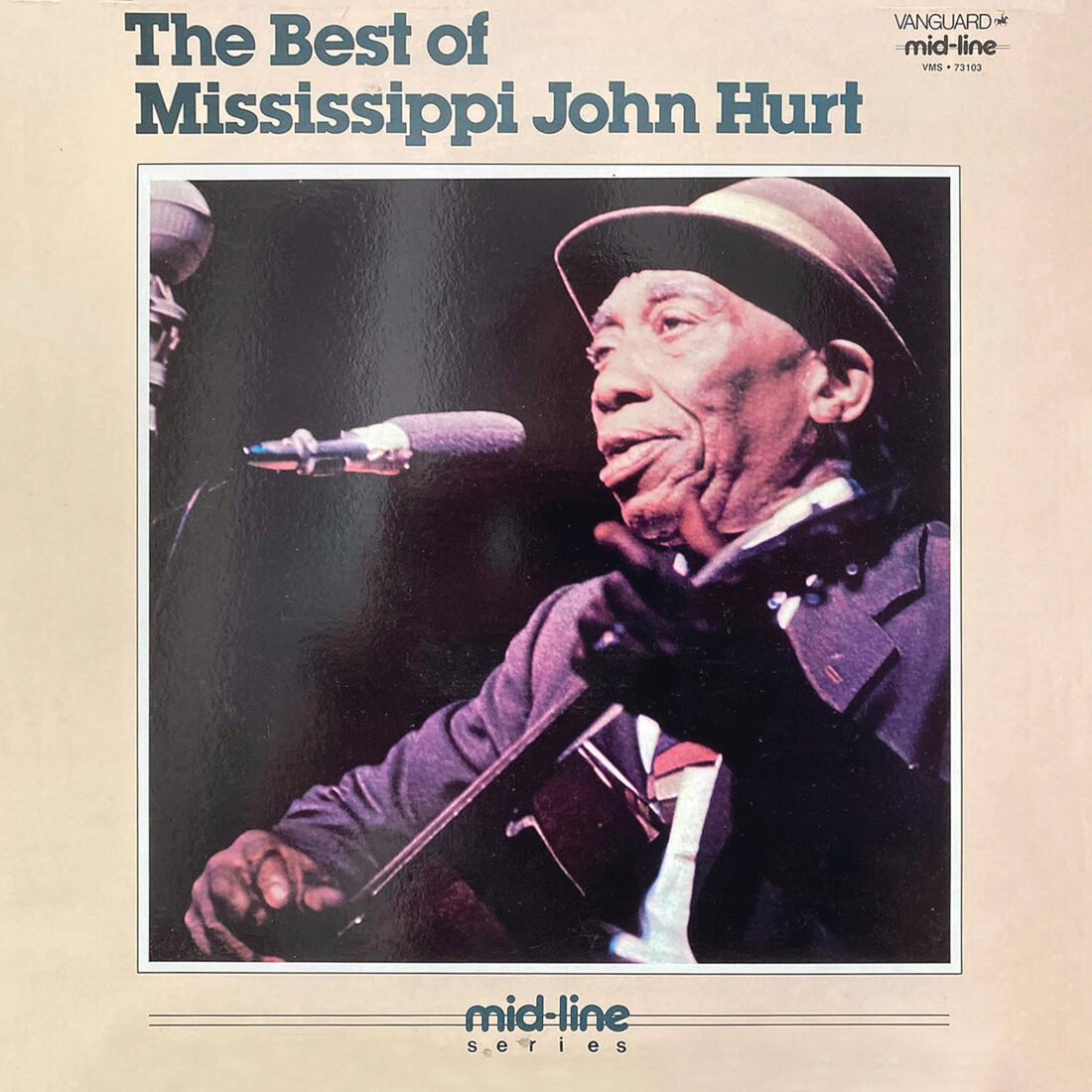

The Best of Mississippi John Hurt (1971)

Mississippi John Hurt

“This live album was part of my dad’s collection and was really influential to me. It was recorded in the early sixties, at Oberlin College—Hurt’s an old man at that point, but he is still playing so well and singing so beautifully. He was my teacher in how to play stride, because the ragtime guitar is basically the left hand of a stride piano player. So if I could play everything he was doing with my left hand, then I could pretty closely approximate what Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, Jelly Roll Morton, all those guys were doing on the piano.”