Some stories begin at the end. This ending begins with me standing in a Georgia swamp, a place we call the Buzzard Roost, twin barrels smoking and tears dropping into the water. Three sons staring at their father, not knowing what to say. A braced pair of wood ducks hanging over a branch of a pignut hickory. One friend knowing everything, saying nothing. An empty dog stand nailed to a water oak.

For the first time in fourteen years, my finger touched the trigger of a shotgun that morning without Dude sitting beside me. I didn’t know if the gun would even work without him. Sure, it would fire, and maybe even a bird would fall from flight. But for it to work, my swing needed to follow the gaze of an old Lab with eyes too blind to see and ears too deaf to hear, but experience too deep to ignore. Without Dude, I felt lost in the fog of that swamp.

I left Franklin County, Georgia, in 2004. The war was raging in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I wanted to serve my country, so I swallowed my fear of failure and stepped onto a bus bound for Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina. Nineteen years, five tours, and counting, and I’m still not sure I understand what we gained in the end, or what great lesson there was to learn. But as a young marine fresh from combat in the Helmand River valley, I didn’t yet have the circumspection of age, and with an arrogance reserved only for fools, I decided to buy a dog, as if man can actually own a dog.

Dude was no Old Yeller or Little Ann. I was loyal to him, and he was loyal to anyone holding a hot dog. Despite the story I want to tell, there were never any beautiful homecomings. No stepping off a Greyhound, seabag in hand, home from the war, to find my loyal hound waiting patiently. Dude wasn’t that kind of dog. Homecomings with Dude looked a little more like this: Man returns from war. Man embraces wife and children and forgets to shut the door in his excitement. Man spends the rest of the evening on his first day home searching the neighbors’ compost piles for a remorseless, trash-eating glutton.

But however those homecomings went, he was always there. Afghanistan, Iraq, Africa, and two tours on naval aircraft carriers. Dude was there to reintroduce me to my home range after each one. He was there for the birth of my three oldest boys and missed the youngest by only a few weeks. He was there when the hour was late and the house was silent, but the ringing in my ears wouldn’t let me sleep. He was there for the conversations I couldn’t have with anyone else, and his black fur absorbed my tears like swamp water.

His being there began in the spring of 2008, a product of an ad on Craigslist I saw while I was still in Afghanistan. Same place I found my first truck. Same place I found my first apartment. Sometimes, the same place I found my wife (depending on how generous she’s feeling about my storytelling). The thing about that ad that meant the most to me, a boy far from home, was that he was from Georgia. He and I had the same origin story.

He had a blue collar, like me. That’s how the guy who owned his mother knew him from the rest of the litter. The one with the red collar was the dominant male. The pink-collared female could barely make eye contact. The one with the black collar latched himself onto my leg for the thirty minutes my then fiancée and I observed them. But the one with the blue collar made no impression, nor was he impressed. He responded only to food. It was to be the hallmark of his existence. I paid the man $400 in cash, and two days later the pup boarded a flight with me back to Camp Pendleton in California.

I kept calling him “dude,” so that is what I named him. He didn’t want to retrieve, so we did force-fetch in the parking lot behind my Craigslist apartment. He wouldn’t stop barking when I left for work, so I put him in my Craigslist pickup and took him with me. He loved popcorn, so I taught him to use his nose by hiding kernels all around the 525 square feet we called home.

In the process, Dude and I became inseparable. We were like an otherwise fine shotgun with mismatched barrels. I was particular, and he was particularly not. I was focused to the point of missing meals, and he was focused on getting them. We were oil and water, and I loved him.

Dude was also something I desperately aspired to be as a marine: unkillable. Neither overdosing on pain medications I once left unattended, nor consuming a full block of arsenic he found in an adjacent cabin on a family camping trip was enough to put him in the ground. But much as I wanted to believe he was invincible, certain things, like taxes, are inevitable.

In his last few months, I had a rare respite from military obligations. No predeployment workups, no late nights reading every book ever written about some far-off place, and no war. I was home. And in being home, I witnessed the rapid decline of my old dog. More than that, every day he became weaker represented the whittling away of the single constant we’d had in our lives as a marine family in a time of war. Dude was leaving us.

On his final day, I lifted him into another Craigslist pickup and drove to the new vet. Because of the pandemic, she was the only vet within thirty miles of our new duty station in New England who was accepting patients. The receptionist gave me an odd look but didn’t ask questions when I asked her to microwave a bag of popcorn before I brought him in. I placed his bed on the floor of the visitation room and informed the vet that I didn’t give a damn about her COVID precautions. My Dude was dying today, and I was going to be there with him. With a grace that said she’d seen this all before, the receptionist gave me the still-warm popcorn and led the vet out of the room. I could come get them when we were ready.

As I was lying on the floor with his head in my lap, two memories kept replaying in my mind. On his first hunt, I felled two Canada geese in a retention pond. They were big, and he was as scared of them as if they had been twin grizzlies. With my best friend, Earl, doubled over in laughter and disbelief, I stripped to the skin and dove in with Dude. I grabbed one of the geese, pushed him the other, and we brought them to shore together. Dude would go on to become a professional pile driver of geese. I think he knew I had his back.

On his last hunt, I dropped a green-winged teal drake. With all the enthusiasm of a yearling pup, he broke through the ice and snatched the drake from the water. Then he looked at me with eyes that said, You need to come get me because I can’t make it back. It was only ten yards, but it felt like a lifetime carrying him back to that dog stand on the water oak, greenwing in his mouth, knowing he would never stand in the Buzzard Roost again. Earl was there for that one, too, as was a new young spaniel my boys named Tucker. This was his first hunt, and there was fire in his eyes.

I lay with Dude for an hour, feeding him one kernel at a time until the bag was almost empty, talking to him and crying about things he didn’t understand before I went to get the vet. He died with a belly full of kettle corn. Orville Redenbacher’s, his favorite.

To see him off right, I placed his ashes beside me in the new Craigslist pickup and drove 957 miles south to Georgia, south to home. When I arrived, Earl and I had a few beers, retold a few stories, and reloaded a box of 20-gauge #2 steel shot with Dude’s ashes, each yellow hull becoming an urn. On the last and final day of that season, we waded silently into the waters of the Buzzard Roost. Surrounded b y my sons, my dearest friend, and Tucker, I stood alone.

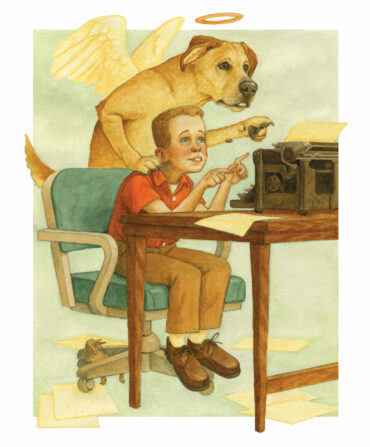

As dawn broke, I looked down into the water, hiding my face from both the searching eyes of ducks overhead and from the impending finality of the moment. In the mirrored surface, I saw the reflection of a black dog sitting on the stand beside me. His eyes were skyward, gaze tracking the coming migration. No longer suffering from the struggles of old age, he was strong again, and I cried as the force of his memory washed over me like a tide.

The whistle of wings crescendoed, and the report of twin barrels shattered the silence as gray ashes mixed with the still-lifting fog. A pair of wood ducks fell into the mist. Tucker’s legs churned like the beating of my heart as he followed Dude’s wake into the marsh grass. Returning from the fog, a burning torch in his eyes, he brought the birds to hand. Ritual complete, homage paid, and a good dog gone.