You probably know homeowners who’ve come across a small but pleasant surprise they had no idea awaited them when they bought their property: tulips popping up where a previous owner planted bulbs, maybe, or the overgrown traces of a footpath through the woods. But there are surprises, and then there are surprises.

“We didn’t even know the waterfall was there when we bought it,” says Mary Palmer Dargan, of the ferny Rivendell of woods and streams that surround the homestead she and her husband, Hugh, gradually jigsaw-puzzled together in Cashiers, North Carolina. “We didn’t know we owned it.”

These days, it’s hard to miss what’s now the star attraction of this tract of steep and secluded valley, a calming, two-plus-acre oasis of temperate Southern Appalachian rainforest with a thousand feet of stream bank amid the headwaters of the upper Horsepasture River. The windows and deck of the two-bedroom cottage, perched on the edge of the watershed, all face out toward the cascade across the ravine. When they first acquired the property, though, the couple encountered “a huge, dense, impenetrable rhododendron hell,” Dargan recalls. Fourteen years and two house renovations later, the spread, which they named Fernwood Falls, is far more accommodating: There’s a sunny, cocktail-party-sized expanse of “great lawn” by one end of the house, a network of stone steps and mowed paths serving as navigable slopes to the valley floor and streambed below, and (by Dargan’s estimate) at least nine little seating nooks tucked throughout the grounds, coaxing a visitor to dawdle awhile. But the spot suggests not so much a conquest of nature as a collaboration. “It’s not manicured,” Dargan says, “and it doesn’t want to be.”

Something of a force of nature herself, Dargan knows a thing or two about what a residential landscape does and doesn’t want. A Tennessee native and descendant of Pocahontas’s sister Cleopatra, she and Hugh both worked in that field even before they married almost forty years ago, and hundreds of designs by Dargan Landscape Architects appear in Atlanta, New Orleans, the South Carolina Lowcountry, and beyond. Along the way she’s written books—Timeless Landscape Design: The Four-Part Master Plan, Lifelong Landscape Design, and others—taught landscape architecture and planning at Clemson, and created an online design course for hobbyists and homeowners called the Placemakers Academy. She’s also an amateur dog handler, entering her and Hugh’s two Boykin spaniels, Henry and a sweetly energetic one-year-old named Meade, in hunt tests and field trials.

An afternoon stroll with her around Fernwood Falls, not surprisingly, becomes both a crash tutorial in botany and purposeful design and a window into her passion for landscapes, and this landscape in particular. Dargan points out a hedge of Limelight hydrangeas atop a rock wall bordering the lawn: “It creates a green wall. We didn’t want to see headlights.” A cluster of tall tiger lilies are “the bomb”; a Flame Thrower redbud at a corner of the lawn is “a real rock star”; a cardinal flower beside the stream is “one of my pets.” The stems of a Pacific Fire vine maple turn bright red in wintertime, for a blast of off-season color. There are enormous hostas transplanted from their previous home in Cashiers, and little natural wonders the Dargans have named over the years: the “bear’s den,” a grotto under a creekside boulder; and “the meditation log,” a mossy stump that settled here long before the Dargans did. The stream and its banks are home to brown and native brook trout, salamanders, bright orange crawfish that scurry away the instant you spot them.

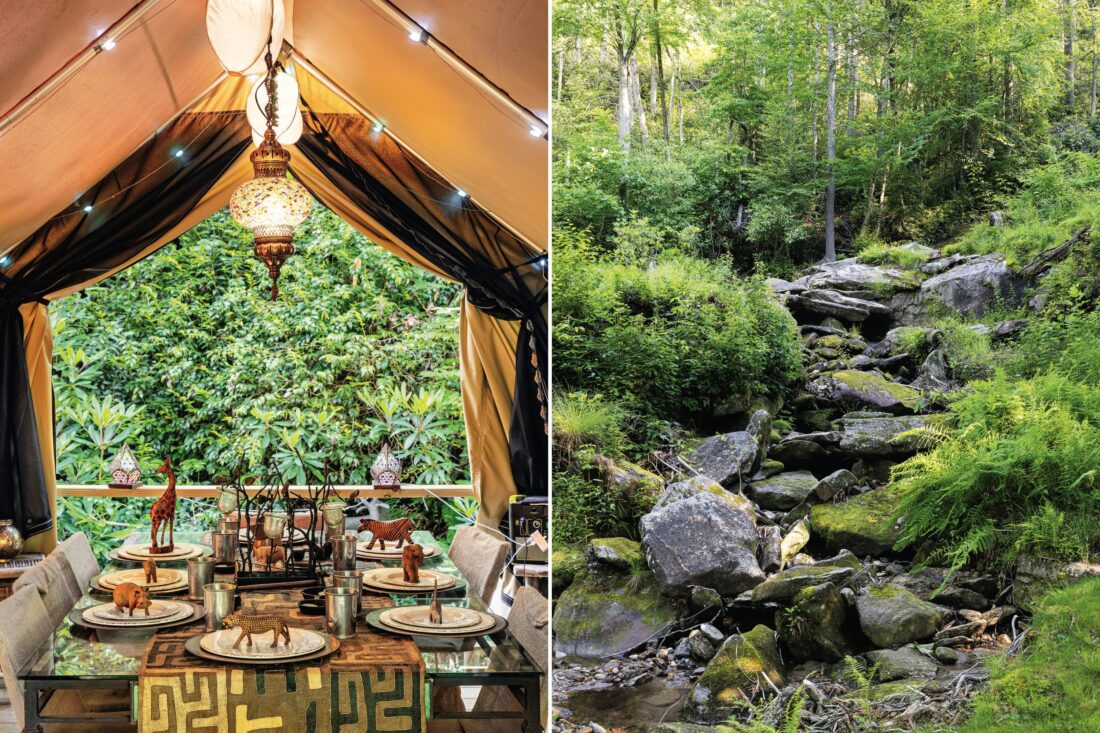

Pockets of man-made habitat appear in the watershed, too. The Dargans installed a pair of safari-style platform tents across from the waterfall: the “sleeping tent,” guest quarters complete with a separate shower enclosure and a propane pizza oven (which is also “the bomb”); and the “Out of Africa tent,” which they furnished with souvenirs brought home from visits to Dargan’s brother who lived in Cape Town. “A property has a story to tell,” she says. “You just have to unravel it.”

Inevitably, the rambling garden tour leads to a perch on a granite boulder at the base of the waterfall, its rocky flume angling obliquely for perhaps seventy feet or more along the slope, and terracing hundreds of feet more up out of sight. Come summer, the falls’ torrent slows to a relative trickle, but the gurgle and splash of the tumbling current are no less mesmerizing. “I love the sound of water,” Dargan says. “I guess it puts your brain in a delta state”—the frequency of brain waves linked to deep meditation and dreamless sleep. As it happens, another chapter in the story of Fernwood Falls is about to unfold; the couple is selling the spread to help them tend to Hugh’s health. But even so, in this spot it’s hard to imagine feeling anxious or apprehensive. Humbled, possibly. At peace, almost certainly.

“The words ‘the spirit of place’ come up a lot,” Dargan says quietly as thunder rumbles somewhere in the distance. Even as the couple prepares to move on, it seems clear this little valley will never quite leave them. “Certain places just make you feel enlightened. This feels like that to me. It takes you out of yourself. There aren’t that many places that let you do that.”