What you need to know is that my wife isn’t great at directions. If you ask, she won’t be able to name roads or estimate distances. If you’re lucky, she’ll gesture vaguely one way or another before just giving up. And yet—and this yet has taken me many years of marriage to fully appreciate—she is always to be trusted when you’re turned around on an empty road in Podunk anywhere. “Turn left,” she’ll say at a stop sign, her only rationale that it feels right. Naturally, I spent years turning right, trusting my testosterone-powered internal compass, and always getting us more lost.

But now I listen. I’ve gone bald and we’ve been married for sixteen years, so when something feels right, I say, okay, and off we go. She’s not led me astray yet.

This is why I locked up my office in the middle of a July day when she called out of the blue to ask, “Should we drive to Charleston to get a dog?” The correct answer, of course, was no. We had no business adopting a dog. We had two small boys, taxing jobs, a never-ending renovation project. We couldn’t fold our laundry, so, no, we shouldn’t drive four hours to the coast to fetch a dog in the middle of the week.

On the way to Charleston, we tossed around names for the frazzled-looking guy awaiting us. In the photos she’d seen on Craigslist, he looked something like a long-eared Muppet, but his scraggly beard and wiry fur pegged him as the distant cousin of a goat. We settled on Hank. It pulled from his goofy appearance a kind of dignity suggestive of hard living. Sure, he looked like a seventy-pound stuffed animal gone wrong, but you should see the other guy.

Hank trotted out of the apartment in Charleston wearing a pink collar. He looked sleeker than in the pictures, his beard trimmed and fur scaled back. “We just got back from the groomer’s,” his rescuer said as we shook hands, and suddenly we understood that her earlier text about “taking him to the grandmas” had been a voice-to-text mistranslation of a Charleston accent. We took his leash, but he stuck by us as we roamed the apartment complex. In a canine Field of Dreams situation, all the residents in the place seemed to step from their apartments and release their dogs at once as we walked, animals of all sizes slobbering on each other and crashing into bushes. Hank, though, remained as sweet and chill as advertised, content to stand by us and stare at the ruckus. We knew he’d fit right in among our unfolded laundry and wild boys.

As it turned out, Hank is of purer stock than I, and I should have counted myself lucky to ride in the car with him instead of making fun of his mop-top or those pink-ringed eyes my son would later call “suspiciously human.” He’s a Spinone Italiano—a sought-after breed I’d never heard of. How this purebred hunting dog found himself abandoned to be rescued by a bighearted woman with a too-tiny apartment in Charleston is beyond me. On the drive home, we Googled and found him to be worth thousands more than the two hundred dollars we handed her to cover vet and grooming bills. In the rearview mirror, I looked at him with a newfound respect, calling out his new name. He turned to me and promptly threw up.

My wife and I had made this same drive from Charleston a few years prior with a moving truck carrying our lives. We had decided to return to the North Carolina mountains, to the county where we’d been raised, to the place where my family has been since the late eighteenth century. Up to that point, we’d lived all over—Honduras, Iowa, Peru, Costa Rica, Charleston—but when the stars aligned, we toted everything we’d become back into the ever-present push and pull of home, expecting to settle there for good.

Once back in the mountains, we released Hank from the stinky car, and a couple of things soon became clear: First, he was not, in fact, a year old. He was maybe seven months, with Clydesdale-esque feet beneath skinny legs, and the bouncy demeanor of a full-on puppy. And second, that dog don’t hunt. When we came down the hill toward my grandma’s house on a walk a few days later, I spotted the turkeys in the field long before he did. Nearly upon them, he finally caught sight, nodded once, and trotted on down the road without a second glance. I didn’t mind, but I did wonder if his pacifism had led to his abandonment.

What I did mind was his disappearing. We were fine at first, setting off without a leash onto the hundred acres my dad’s people have lived on for generations. Hank, I’d call to him, and those ears would start flapping on his way back to me. I gave him the requisite good boy, and it seemed enough. But one morning, somewhere beyond the hayfield and the creek, he left me, sending me bushwhacking up the thorny hill, hollering his name and cursing under my breath.

I found him—or I found his tail—sticking out from an old barn we’d long since abandoned at the edge of the woods. It seemed sturdy enough, so I followed him in, the kicked-up dust glittery in the morning sunlight, and found myself in front of a buggy parked there a hundred years ago. I’d never seen it before, so I stepped farther in and imagined the thing attached to horses, an ancestor bouncing along the dirt road somewhere behind me. I touched the carriage as if it might transport me back in time before reaching down to Hank’s springy head and patting good boy.

And so this has become our routine. Every morning—rain, sleet, or snow—Hank and I set out onto the family land I left two decades ago. We climb the dirt road to survey the beehives and Bearwallow Mountain and the long stretches of forest beyond Grandma’s house, and then he leads me down the hill, into the past. Back in that abandoned barn, he takes me beyond the buggy to a bizarre wooden contraption with a small trough and an attached blade. (An email to a knowledgeable historian reveals the machinery to be a nineteenth-century feed chopper.) In the dirt near a rotten sawmill, he digs at a green glass medicine bottle, which I unearth and we sniff together. Near my great-great-grandparents’ empty house, I find him pawing a small opening to an outbuilding, so I reach inside and come away with the shoe of a long-dead ancestor, the sole still hammered in place even as the leather wears away.

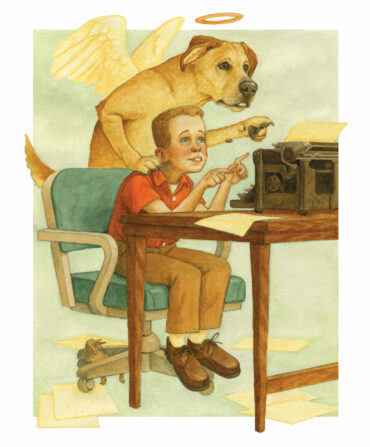

In the year since we brought Hank home, he has proved himself to be a miserable bird dog but a superb artifact finder, an incredible, albeit stinky, museum guide. And he couldn’t have come at a better time. In that office I packed up midday to drive to Charleston, I was supposed to be writing a book about the people who settled the very land we walk every morning. I’d been searching for stories and digging through archives and accessing land records, but I apparently needed a Spinone Italiano to find their stuff hidden in plain sight. Holding these objects brought my people to life. Suddenly their stories had concreteness, their lives a new texture. (And my book fresh legs.)

On a crinkly recording from fifty years ago, my great-grandmother Azalee tells of the first of this line to settle our land. The men drove the livestock and a schooner wagon, she says, and the women loaded down a boxcar with steamer trunks and housewares. Some weeks after I listen to that tape, Hank leads me up a hill covered in brambles, and we turn up wagon wheels that might once have held that schooner aloft. Days later, he pulls me to an old shed, where we loose a board and slide inside. Here before us are the very steamer trunks that started our life here, taken over by critters but enduring nonetheless.

On these walks, I always touch everything, holding the items we find to feel their weight, to guess at their pasts. But I leave all of it as is, tucked away and hidden. I call his name and aim us back home, confident Hank will lead me back there again when it feels right.