Dear Burt –

Damn it to hell. I waited too late to write this letter. We’ve corresponded a few times through your assistant Suzanne, and I’d been meaning to send along my latest novel—dedicated to you. A lot of people this summer have asked me about that dedication. You mean, that Burt Reynolds? I always answer: Is there another?

Do you know him? He reads my books! Burt is a big reader.

Have you met him? No. But I will someday.

I hope you knew how much your movies, your cool style, have meant to me both as a writer and a Southerner. After a few bourbons, I’m quick to point out that Smokey and the Bandit wasn’t just a car chase film. It was about us racing into the new South, knocking corrupt cops, racist bikers, and the slow mean old ways the hell out of the way. Each one of those films, those core action movies—Deliverance, White Lightning, Smokey and the Bandit, Sharky’s Machine—had so much to say about the emerging Deep South. The clash of good vs. evil, man vs. nature, the Bandit vs. Buford T. Justice.

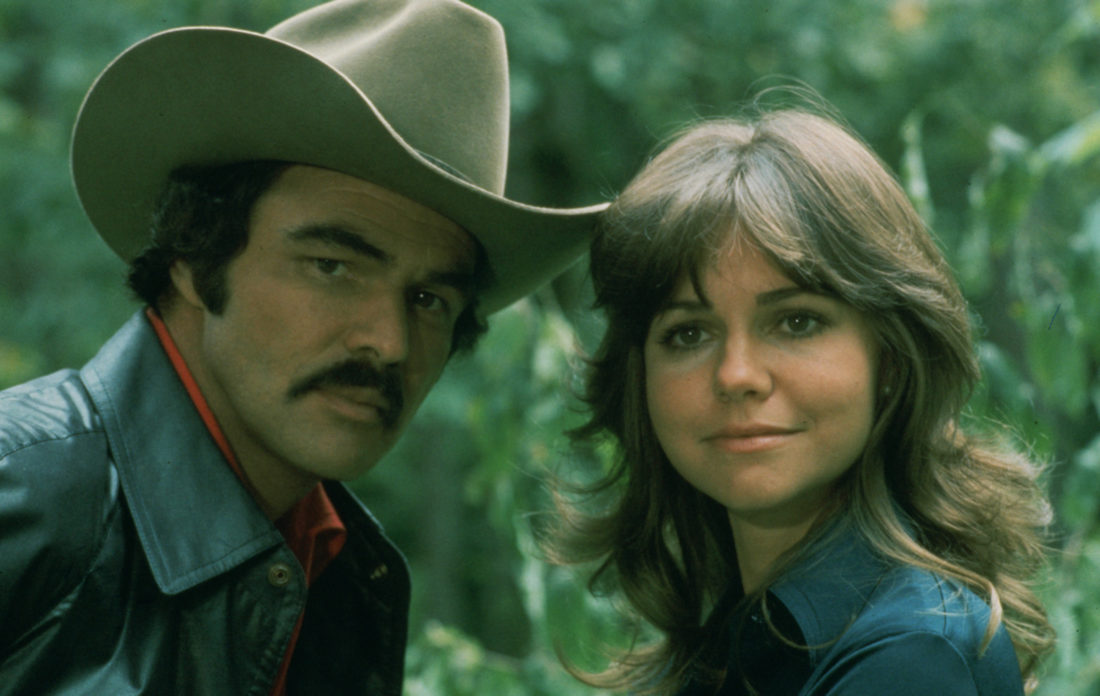

Photo: Courtesy Smokey and the Bandit ©2016 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Burt Reynolds as “Bandit” and Sally Field as “Frog.”

In Sharky’s Machine, you stood as tall as Gary Cooper in High Noon, not in a Western town but a gutted, eerie shell of downtown Atlanta. It was before Atlanta rebuilt for a second time, and you could sense the excitement of possibilities. This had to get bigger and better. So often with your films, it’s the old against the new, the rigid past that seems to never die, but a tough and moral good ole boy can truck or shoot his way through it anyway. No matter the odds. No matter how many cops chase you through the Okefenokee.

As a kid born in the 1970s, I don’t ever remember a time that there wasn’t Burt Reynolds. I always thought of you as one of our own. For a few years, I was an exiled Southerner, an Alabamian living in such far-flung outposts as Detroit, San Francisco, and St. Louis. And you reminded me of people I knew, someone that could be part of my family. You played football at Florida State at the same time my dad played football at Auburn. And you were a man I could look up to, someone who removed their helmet and went on to become an artist. This was key for me. I wanted to be like you. As an often worried and stressed out student-athlete, I wanted to develop your cool.

I developed a lifetime love of cowboy boots, Coors beer, and cool belt buckles. (My treasured possession is one from the now defunct Burt Reynolds Ranch.)

When I played football at Auburn, I was known to often host a Burt Reynolds Night at the football dorm. My teammates and I were on a pretty constant rotation of White Lightning, The Longest Yard, Smokey and the Bandit, and Hooper. One night, a teammate walked into Deliverance at the infamous Ned Beatty scene and yelled, “What in the hell are y’all watchin’ in here?”

Another time my pal Richard Shea joined a Hooper showing and announced, “My dad helped blow up that bridge!” I learned that the final wonderful scene, where Burt and Jan Michael Vincent face glory or a certain death, was shot outside Tuscaloosa, and Shea’s family construction company helped with the demolition.

You really helped me get through my football days at Auburn, man. I had coaches that made the prison guards in The Longest Yard seem like Boy Scout troop leaders. I took a cue from you. Grin through the bullshit. Don’t ever quit. Ever.

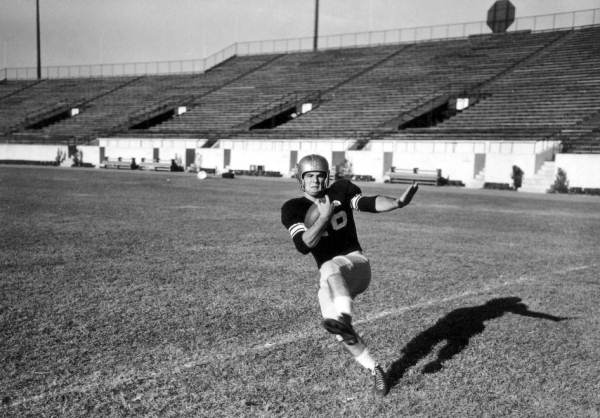

Photo: Courtesy of The State Archives of Florida

Burt “Buddy” Reynolds in 1954 at Florida State University, where he played halfback on a football scholarship.

To everyone, you were always a hit. I knew you. My teammates knew you. Burt Reynolds was family.

Hell, Burt, even my grandmother loved you. A proper Southern woman, born and raised in Greenville, Alabama, she kept up with you in the tabloids. She was obsessed with you, Elvis Presley, Pat Sajak, and Richard Burton. But when I was in high school, it was pretty much all Burt. We talked about you often. She thought you were handsome and funny, loving that time you showed up on The Golden Girls to take Sophia out for lunch. I was at her house any Sunday night that B.L. Stryker was on, a show created by our mutual pal, Robert B. Parker. I recall vividly lying on her living room floor and watching you and Ossie Davis bust heads on her old console TV.

She kept clippings of you in our family photo album. And during that whole ugly thing with Loni, when you shaved off your mustache—shades of Samson—and wore that purple suit while offering to take a polygraph, our support was unwavering.

My dad’s side of the family loved you, too. My grandfather sold moonshine, and my uncles ran liquor for him across the state of Alabama in souped-up rides. What happened to you in White Lightning—avenging your brother’s death—might’ve happened in my family. One of my favorite memories as a kid is coming home to Alabama during your high times as king of the box office. My family had a CB radio in our station wagon, and as a nine-year-old, I was able to act out all my Bandit fantasies. Not to mention that when we got to Lamar County, Alabama, I was able to hit the backroads with my wild teenage cousin, Keith. Keith liked to put the pedal to metal like you, flying down those dirt roads and sliding into those tight turns.

I loved it when he drove slow and easy past a cop, waving to a him. “You see that guy?” Keith said. “That’s the only cop in town.” Then he floored it.

What damn fun! You made living down here, being a Southerner, something to appreciate and love. Your films showed the rugged beauty of the landscape, the kudzu-covered hills, misty mornings on back highways, rough and tumble juke houses that served cold beer and hot barbecue. You gave the South someone to root for, someone to emulate, and you did it all with style and that cool-as-hell don’t-give-a-damn attitude.

I want to thank you, Burt. I feel terrible that in so many interviews you had to discuss your failures, Stroker Ace, Cannonball Run 2, or even that time you invested in both the USFL and the Po’ Folks restaurants. But let’s not talk about that now. Let’s go back to the seventies, when I was a boy looking for someone I could emulate and admire, someone like me and my family, and someone who took on the system and bad old ways that we all never wanted to see again. Let’s talk about you taking down that rotten Ned Beatty in White Lightning, that rotten son of a bitch who killed your brother. Or when you proved a man could fly—better than Superman—in Hooper, you and Jan Michael Vincent jumping that river.

It’s like that wonderful line from Smokey in the Bandit.

Snowman: “And why are we doing this again?”

“Because they say it can’t be done, son.”

And we go. We don’t look back. We don’t complain. We drive fast. We take on the Machine. People we love come and go. Times change. People die. We fly into an unknown future. Remember what you said in your recent memoir? “There’s one thing they can never take away: Nobody had more fun than I did.”

That’s what we all want, in the end. Hope you land safe and sound on the other side of the river, my friend. It’s been one hell of a ride.

Ace Atkins is the New York Times best-selling author of more than twenty novels, including Robert B. Parker’s Old Black Magic and The Sinners. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi, with his family, where he’s friend to many dogs and several bartenders.