James McMurtry answers the phone from one of his favorite places: the interstate. “I like the rhythm of being on the road,” he says in his monotone Texas drawl. “I’m old now, so driving beats loading equipment in and out of a club.”

McMurtry’s recent gigs have seen him previewing material from his exquisite new album, The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy, which is out this Friday. With songs full of impactful detail and unforgettable characters, McMurtry is one of songwriting’s most vivid storytellers, following in the tradition of John Prine and Guy Clark and influencing contemporary songwriters like his pal Jason Isbell. While McMurtry’s songs aren’t autobiographical, the new album contains snippets of his life: The title track draws from hallucinations his late father—the acclaimed author Larry McMurtry—experienced while suffering from dementia in his later years. One of his own dogs gets a mention in the slow, soaring gallop of “Back to Coeur d’Alene,” while tracks like the mournful, 9/11-themed “Annie”—featuring Sarah Jarosz on banjo and harmony—see McMurtry revisiting his interests in political and social commentary.

Today, Garden & Gun is proud to premiere The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy, which shows the sixty-three-year-old songwriter is still at the height of his powers. Stream the album below, and read on for our interview with McMurtry on his songwriting process, fishing, and his love of Kris Kristofferson. The album is available to order here, and look for McMurtry on tour, with dates booked through September.

You said in an interview recently that you don’t write about yourself, but these new songs, such as the title track, seem to have a slightly more autobiographical thread.

After he passed, my stepmom asked, “Did Larry ever talk to you about his hallucinations?” They were also a black dog and a wandering boy. I said no, but that sounds like it would make a cool song title. I pull details from life, but the stories are generally fiction.

And you said once that you write from a female perspective.

Sometimes, yeah. But people don’t get it because it’s sung in my voice. I don’t spell it out directly, like John Prine did with “Angel from Montgomery.” He comes right out and says, “I am an old woman.” That’s hard to beat.

Do you have goals when you’re trying to make a record?

Indeed. I’m trying to get enough songs for an album-length work. I’m still geared to that, even though the world went on random shuffle decades ago. Every now and then, I have to put a record out because I need you guys to write about me so people will know I’m out here touring.

You cover Kris Kristofferson’s “Broken Freedom Song” to close the album. How did he influence you?

He was my greatest inspiration as a songwriter. As a little kid, I wanted to be Johnny Cash, but I hadn’t considered where songs came from. My stepdad handed me the first Kristofferson record and said, “Listen to this.” I liked the way he phrases things. I liked his voice. I didn’t know at the time he was a Rhodes scholar, but he had very precise verses you could sing or talk with equal effectiveness. One of the first shows I ever saw was Kristofferson in Richmond, Virginia. It was such a great time, and I thought, “Yeah, I want to do that.”

“Sons of the Second Sons” has a social component to it. What was the thinking behind that song?

I recently read a book called Caste: The Origin of Our Discontents, which includes many references to the Jim Crow railroad car. It was the first time I really saw how Black people would travel south from New York City in any car, like any human being, but when they got to Union Station in Washington, D.C., they had to move to the back of the car.

Do you read a lot?

I don’t. I might read a book a year, and I skip a lot of years.

Not even your dad’s books?

I read a few of them, but there are a bunch I missed. I don’t have a great capacity for prose.

Your father famously wrote a certain number of pages every morning. Do you write every day?

No way. I write when it’s time to make a record. My son is a musician and writes every day like my dad. The two of them keep the wheels turning. I just never worked that way. As a kid, I did my homework on the school bus right before class.

Do you have a stash of songs you can pull from?

I had a laptop with everything on it, but I lost it. We were doing a one-off gig, so everybody took cars instead of renting a van. I had a canoe on top of the shell of my truck, and I usually leave it up there, because if I take the boat down during the summer, I might talk myself out of going fishing. I was moving gear around, and I put the laptop under the canoe and drove off. So it probably blew off on I-35 somewhere in Denton County [Texas]. But I’ve gone back to writing on legal pads; there’s something about putting a pen to paper.

Do you go fishing frequently?

I go fishing some. I usually go to the San Gabriel River, where it runs into Granger Lake in Williamson County. I catch a few white bass and crappies when they’re running.

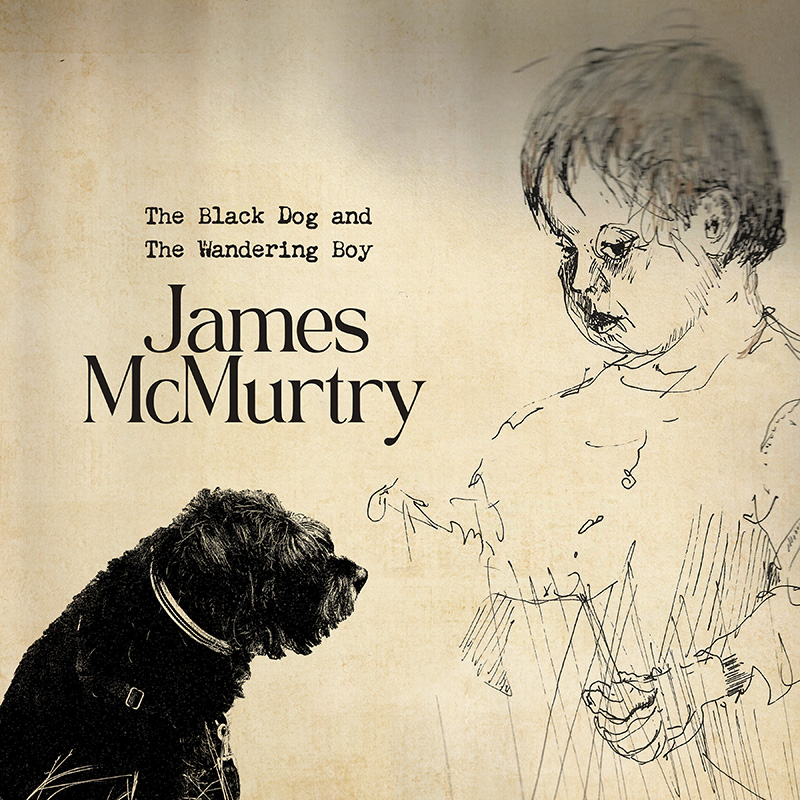

Your dad was pals with Ken Kesey, and you found out that Kesey did a drawing of you, which became the artwork for the new album.

I found it among Larry’s stuff after he died. I thought maybe my mother had drawn it, but she said, “No, Kesey did.” I thought it would make the perfect cover art, and then I superimposed a picture of one of my dogs.

How many dogs do you have?

Two. The big one is named Carson, after the writer Carson McCullers. My girlfriend named the other one, Mikey. He’s a rescue dog and was mistreated, so he always woke up thinking he was in trouble. It took him a long time to loosen up and enjoy life. And once he finally did, he always bounds down the stairs. If I’m moping around in bed, he’ll jump up there and be like, “Come on, get up. There’s nobody yelling at us.”

Also: Watch McMurtry’s 2015 Back Porch Session at the G&G offices.