As the long-standing social order of Jim Crow and racial segregation finally began to crumble in the 1960s, the South was in a state of turmoil. But while Alabama governor George Wallace stood in a Tuscaloosa doorway to block integration in 1963, roughly a hundred miles up the road in Muscle Shoals, white musicians raised on R&B and early rock and roll were working side by side with Black artists. In what author and ethnomusicologist Rob Bowman calls “the unlikeliest story you can ever imagine,” together they were cranking out monster hits.

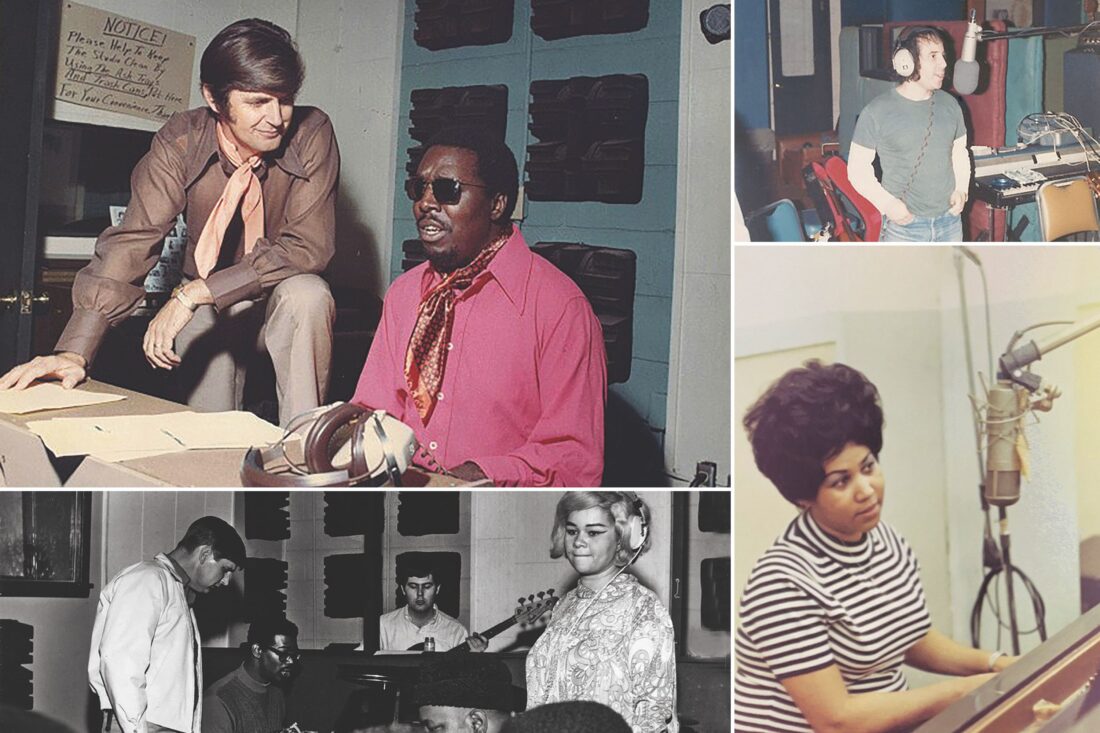

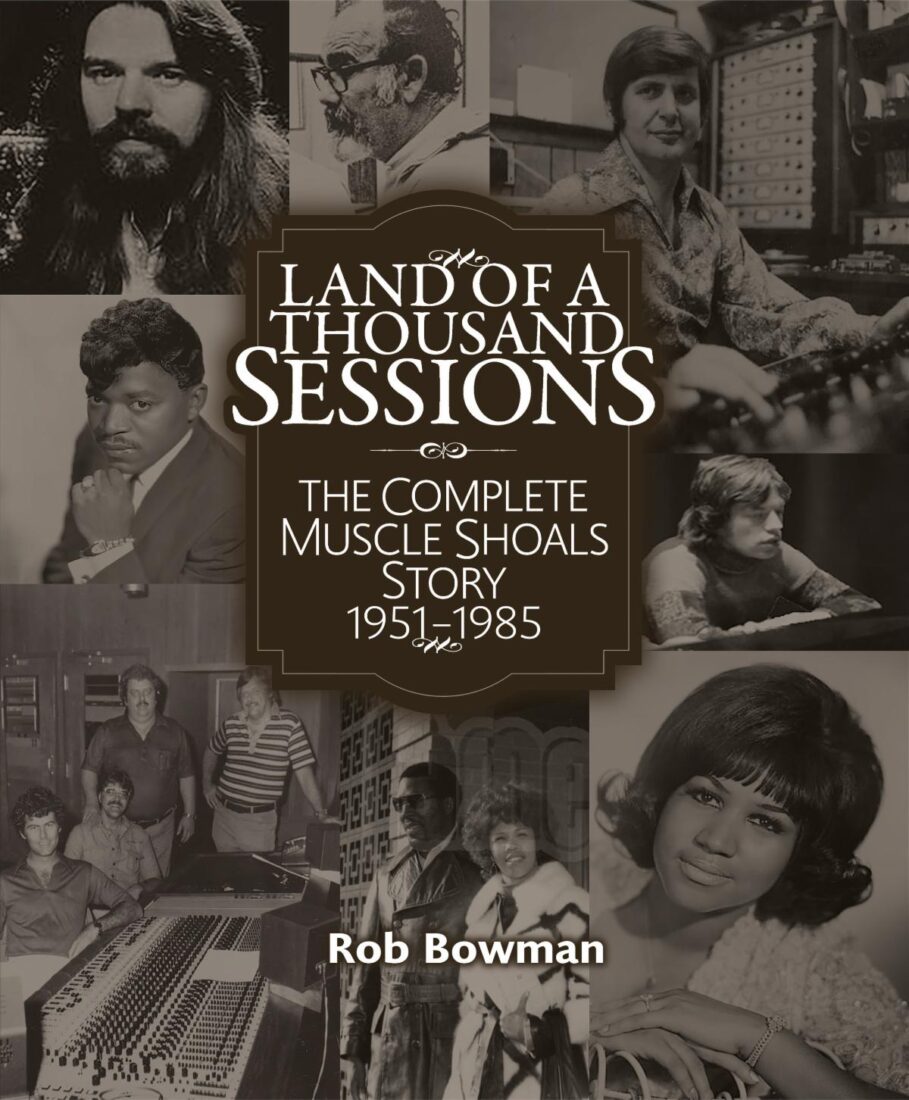

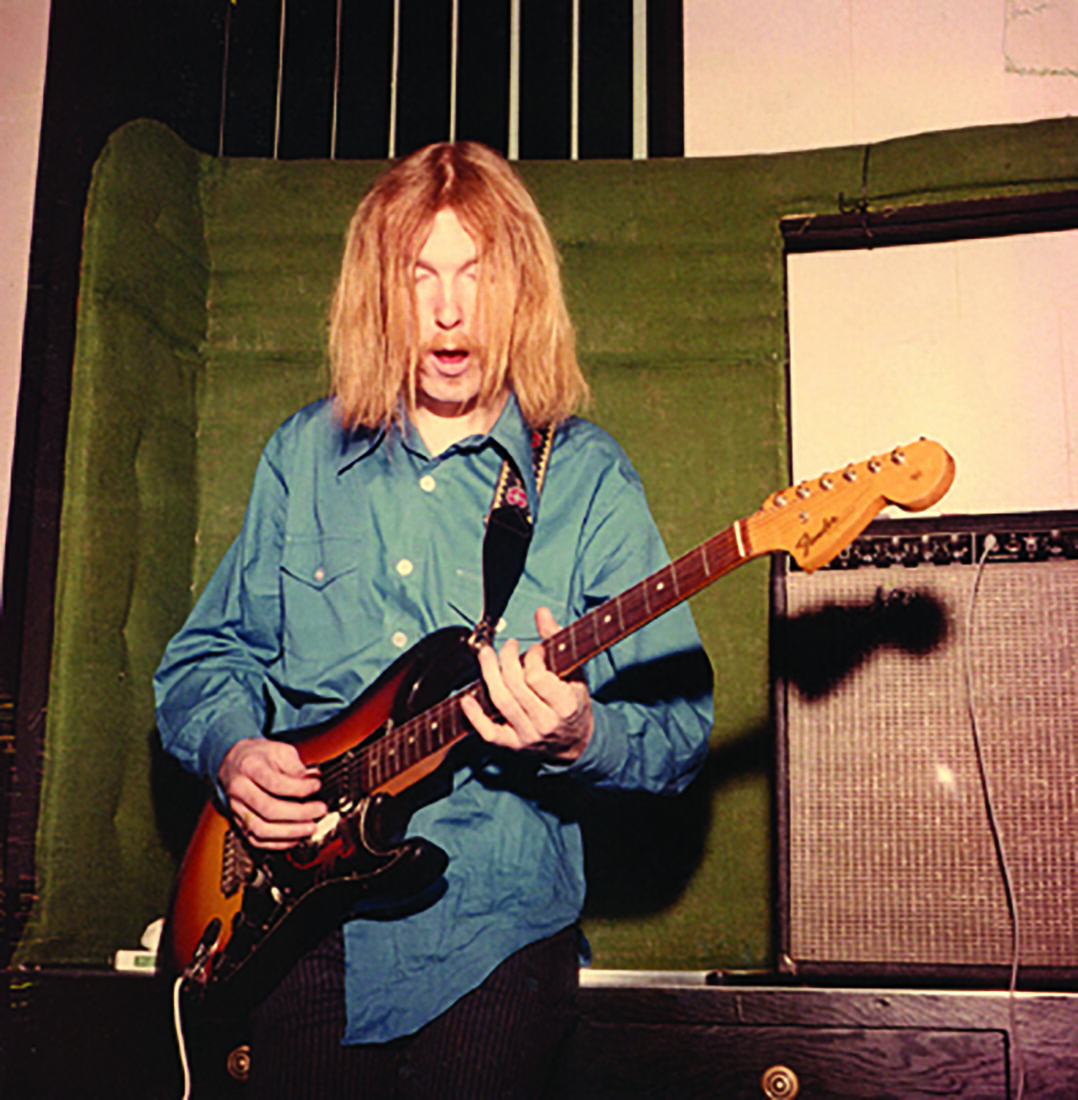

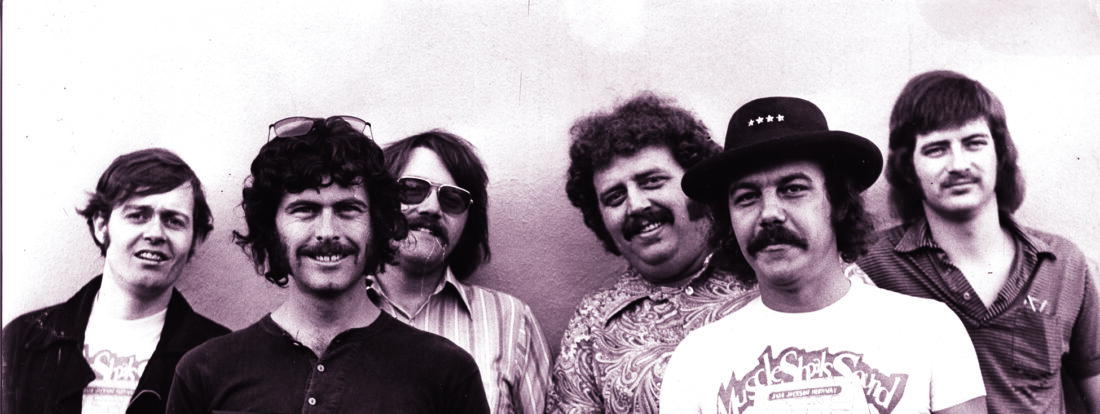

The common thread, as Bowman explains in his forthcoming 745-page book, Land of a Thousand Sessions: The Complete Muscle Shoals Story 1951–1985, out November 25, was the area’s network of recording studios. Places like FAME, the region’s first successful studio, produced such iconic tracks as Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally” and Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman.” By the end of the 1960s, some of the studio’s key session musicians—David Hood, Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson, and Barry Beckett, collectively known as “the Swampers” in part thanks to a lyrical callout by Lynyrd Skynyrd in “Sweet Home Alabama”—had left FAME and its owner, Rick Hall, to create Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. There, they produced hits like the Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses” and “Brown Sugar” and Paul Simon’s “Kodachrome.”

“I find it incredible that I can listen to Don Covey or Etta James or Aretha Franklin, and then I go listen to Traffic and Bob Seger or Lynyrd Skynyrd, and it’s the same guys,” Bowman says. “The Muscle Shoals guys were so adaptable, and that’s what made them able to work with hundreds and hundreds of different musicians along all parts of the American spectrum.” Since those early days, FAME has hosted artists such as Alicia Keys, Margo Price, Allison Krauss, and Jason Isbell, who recorded at the studio during his time with Drive-By Truckers (featuring David Hood’s son, Patterson) and as a solo artist.

FAME and the surrounding prolific musical region are also the subject of a new five-thousand-square-foot exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville. Opening November 14, Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising tells the region’s story through video interviews, interactive displays, and artifacts, including the baby grand piano Franklin played on “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” and guitars played by Duane Allman, Pop Staples, and Mac McAnally.

Bowman interviewed nearly one hundred of the key players in the Muscle Shoals story, from Mavis Staples to Mick Jagger, to create the definitive history of this Southern music mecca. We spoke with him about what made this region of northwestern Alabama an epicenter of popular music.

The lyrics to “Sweet Home Alabama” introduced the Swampers to millions. How did developing at Muscle Shoals impact Lynyrd Skynyrd?

Ronnie Van Zant [Lynyrd Skynyrd’s vocalist] would hang out in sessions during the day—because Skynyrd was cutting at night, off hours—just to watch the way the Swampers worked and the way Jimmy Johnson would direct the other players, as well as the lead singer. He learned a ton.

And Jimmy had a huge impact on how that band sounded. If it wasn’t for the fact that Alan Walden, the band’s manager then, got the original demo tape turned around and backwards—so when he played it for the record companies, they heard this really muffled, horrific sound—they probably would have been signed off the Muscle Shoals demos, and Jimmy would have been producing those first records. Unfortunately, Alan got that tape garbled, and it got rejected by everybody. That tape eventually came out [as Skynyrd’s First: The Complete Muscle Shoals Album in 1998], and we can all hear it sounds great.

Willie Nelson wrote hits for other people, but after recording at Muscle Shoals, he came into his own. What did Muscle Shoals have to do with his success?

Willie shows up, gets out of his [VW] Beetle station wagon, and grabs Trigger [his guitar]. He walks into the studio, meets everybody, and goes, Okay, let’s cut. And those guys were a little nervous. They had cut great R&B, rock, and pop records, but Willie Nelson’s [sound] was something they were going to have to work at. Wille’s timing is very idiosyncratic, but they adapted to his playing. They nailed it.

Willie was happy, but he had a producer and A&R guy in Nashville who said, I think we need to try this with Nashville musicians, so they recut the whole album in Nashville and then sent it up to [Atlantic Records executive] Jerry Wexler. Jerry was pissed beyond belief—it sounded like a Nashville record, and nobody wanted that. So, Jerry fired the guy in Nashville and put out the Muscle Shoals tapes, and of course, that became the blueprint for Willie’s second career as a country outlaw, recording songs in a very different way than the way Nashville cuts and records them, with very different lyrics. I mean, [Willie’s 1974 album] Phases and Stages is about a divorce. One side is the man’s version, the other side is from a woman’s point of view. It’s brilliant. And it was a very successful record.

What, in your opinion, is the golden era of Muscle Shoals?

I’m a massive Staples Singers fan. I’d say my two favorite records ever cut there were “I’ll Take You There” by the Staples and “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin, but I’ll probably second guess myself five minutes from now. Ultimately, I’ve gotta go with ’65 to ’68, because that’s when you get the Aretha record. That’s when you get Wilson Pickett. That’s when you get Etta James’s “I’d Rather Go Blind,” one of the greatest R&B ballads ever. Plus, you get all those great Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham songs—they’re one of the top five, maybe top three R&B songwriting duos in history.

The epilogue is devoted to the latest wave of Shoals artists, like Patterson Hood with the Drive-By Truckers and Jason Isbell.

Oh, it’s an amazing renaissance. It’s in some ways not connected to the studios that originally started it, although several people, like Isbell and Patterson, cut at FAME. But Muscle Shoals isn’t a studio system with one set of special players churning out all these great records by different artists every week. It’s different now. There are these self-contained bands from the area like Alabama Shakes, the Civil Wars, and the Secret Sisters. All these groups are aware of the history, and most of them have had some contact with many of the legends who are still alive; they learned things from them. It’s different kinds of music. It’s a different world and a different period. But it’s wonderful for the area, and it’s great music.