In April 2019, I headed thirty miles out of New Orleans to LaPlace, Louisiana, driving along thickets of cypress to a squat veterinary hospital and the closest internal medicine specialist I could find. I dropped off Scout, my three-year-old pit-hound, for an ultrasound, and drove to a coffee shop to wait. As I ate a kolache the size of my forearm, I calculated whether this vet visit would finally overdraw my checking account.

We were here—Scout and I—after more than six months of mysterious medical emergencies that I referred to, in polite company, as “penis problems.” When prompted to elaborate, I usually told nonmedical professionals that this involved instances of incontinence and…unsheathing…in an otherwise healthy dog. It had been almost a year since I became Scout’s primary owner, and much of that period was marked by urgent visits to the vet, anti-inflammatory prescriptions, and bedsheets changed at 3:00 a.m.

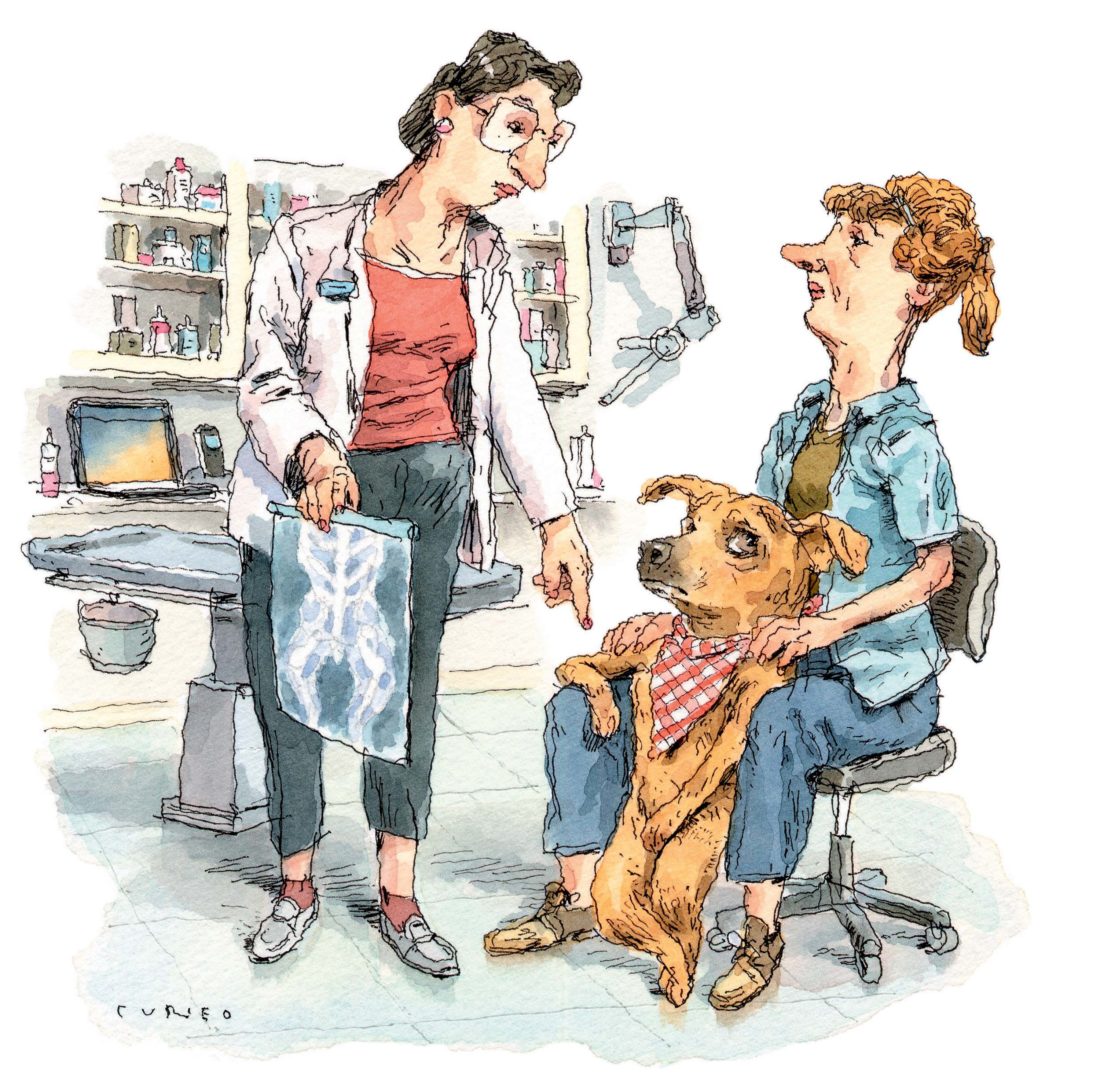

After thirty minutes, I drove back to the hospital, where I sat on the floor clutching a shaking Scout. We were referred to this specialist by his primary vet, who suspected his issues stemmed from prostate cysts, which could require expensive surgery and a biopsy. The specialist pulled up a slide. “Here you can see his prostate,” she said, gesturing to a grainy lump. She pointed out a spatter of spots: cysts. “It’s irregular,” she continued, tracing the outline with a finger. “The shape doesn’t look normal for a neutered dog of his age.”

“Which brings me to the next slide,” she continued, scrolling forward. “Did you know he still has a testicle?”

I had never wanted a dog. I moved to New Orleans in 2016, rudderless and jobless. My boyfriend was there, and I loved the blooming jasmine and brass horns and, inexplicably, the humidity, and so it seemed like a nice enough place to stay. He began looking for dogs within a month of our moving in together, despite my protests; it was too soon, I was too new to the city, couldn’t we wait? But he insisted, and scoured adoption sites until he settled on Scout, a gangly caramel-colored mix with the stoic, contoured cheeks of a pit bull and the floppy ears of a hound.

Scout came home with us after Thanksgiving. He was skittish and wary of human touch. His foster family had kept him for a month after their neighbor dropped him off on their doorstep with a crate dented with kick marks. The neighbor told them she had picked up Scout on Bourbon Street, where a man was kicking him and ashing cigarettes on his back. She offered the man fifty dollars for the puppy, and he refused. Emboldened, perhaps by a sugary daiquiri, perhaps by something stronger, she picked up Scout and ran. Now he was in my home, thirty-odd pounds of patchy, chai-tea-colored fur, with a white belly speckled with tan spots, and two bright white toes. He had the most expressive eyes I’d ever seen on an animal; bulging, deep features set back in a narrow face that reminded me of, at times, a bat, a rat, or Yoda.

I grew up with golden retrievers my family had adopted as puppies, confident, playful dogs with sunny dispositions that never had a reason to doubt a human’s intentions. But Scout was leery at best, neurotic at worst. Thunder would make him nervous, as would light rainstorms, fireworks, bigger dogs, and the neighbor who moved everyone’s trash cans on Sunday. He was antsy about being alone, even for minutes. Once he became comfortable, though, he bonded quickly. He needed to sleep touching a human, either curled into the crook of a knee or spiraled onto a pillow almost touching my head. We ambled along cracked sidewalks to the park by the Mississippi River and shared frozen mango out of the bag. His fur regrew, and long walks bulked up his sinewy frame. I hauled him onto hand-built rafts along the bayou and held his leash as he eagerly took in his first Mardi Gras parade.

Like any good New Orleanian, he thrived in a costume. Under the TV was a cluster of bandannas—tie-dye, neon, Mardi Gras print—and every few weeks, I laid out three options and implored him to sit on the other side of the living room, his tail thumping vigorously. I’d call him and he’d sprint over, tumbling into my arms and then snatching up a bandanna, thereby choosing his outfit. Every morning, he crept to my face as I awoke, sniffing my cheeks and wagging with that same ferociousness, genuinely ecstatic that we both made it to another day.

I had never had an animal so dependent on me; I had never lived in a city that felt so much like home. I fell deeply in love with Scout and New Orleans, and less attached to the relationship that had brought me to them. When the latter finally ended, it was assumed Scout would stay with the man who had chosen him. But I fought, tentatively at first, and later more ardently, to keep him.

When I left, Scout came with me. Now we were both wary. His separation anxiety kicked in, and I was equally apprehensive, struggling with the emotional and logistical details of leaving a long-term relationship. We spent hours lying out by a friend’s pool, and at night we slept on couches and in beds abandoned by friends of friends for summer vacation while I searched for a home. Eventually I found a spot close to the bayou, where we could walk on grassy paths along the water up to City Park.

Soon after I moved into my new house, the problems started. Was it a UTI? Inflammation? Anxious licking while I was at work? His behavior skewed as well; his barks deepened when the mailman approached, and he growled more at my roommate’s visitors. In the fall, I drove him up to my mother’s, where he snapped at one of the golden retrievers.

But at night, he pawed at blankets to nuzzle closer into my side, or sprawled out humanlike, with his head on the pillow. I rubbed the velvety folds of his ears and despaired, trying to figure out whether this was karma, or fate, or some combination. I had never wanted Scout, and then suddenly I did, desperately, and perhaps my initial hesitation was coming back to haunt us both. The transfer of ownership from my ex to me had been mostly civil. But I still ached with guilt when I coaxed Scout into the vet’s office, tail between his legs, and wondered how many of his issues could be blamed on the turmoil of the past year.

All I had wanted, since the first time he curled up next to me, was to make sure he had the best life possible; to be somewhat worthy of the unconditional love, of the glee he greeted me with every morning. My relationship failed, and Scout suffered the consequences, and here we were, in yet another vet’s office, surveying an ultrasound that would cost more than a month’s rent.

“Here’s the testicle,” the vet said, pulling up the next slide. “You did say he was neutered, right?” He was adopted from the shelter in a nearby parish, I told her, and the paperwork noted he had been. There was a chance he could have been born with three balls, she said, but it was rare. It was more likely it was an incomplete neuter, and that the remaining testicle—and associated testosterone—caused not only his funky prostate and “penis problems,” but also his spurts of aggression.

Scout and I trotted out minutes later, exuberant. I hadn’t failed my closest companion; he had simply been wandering around with one testicle too many! The shelter rechecked its records and confirmed there was something off about the initial neutering, then completed the procedure free of charge. Within two weeks, we were back to our route along the bayou. Within months, Scout had mellowed and matured. We moved into another home, where he lolls on the porch amid fallen fuchsia crape myrtle petals, and I no longer worry about whether or not he was supposed to come with me those years ago. We ended up exactly where we were meant to be.