Evan Voyles remembers lying in the way-back of the family station wagon—a butter-yellow 1960 Rambler—watching the neon lights flash by as the car passed through towns on the way to Abilene, Texas, en route to see his grandparents. The Voyles family lived in Austin—had been there generations—and Evan’s mother disdained the kaleidoscope of lit signs that had sprung up on Burnet Road, then the main artery in and out of town. “The neon jungle,” she called it. “Nice people don’t go there.” But her son was mesmerized.

Today, at age fifty-eight, Voyles likes to drive every evening past the mile-long rainbow of signs on South Congress Avenue, Austin’s premier commercial strip. The stretch of bars and boutiques evokes those golden years of neon, but just as important, it’s a flickering nightly exhibition of Voyles’s life’s work. The starry-eyed boy grew up to become a master sign maker, and his work now defines a large part of Austin’s modern visual identity. Like his signs, he is a throwback to an earlier version of Austin—a hippie cowboy with long graying hair, beat-up boots, and a bandanna.

Voyles tells his road-trip story from across a pockmarked worktable that stretches the full length of his studio, in one half of a hundred-year-old former corner grocery in South Austin. He’s been working out of this space for twenty years, and by last count he has more than 300 signs around town. Many of them, such as the giant purple SOUL sign overlooking the pool at the Hotel Saint Cecilia, and the red mustachioed pizza twirler at Home Slice Pizza, have become constantly Instagrammed Austin icons. One of the signs on the table today is a classic in the making, a cowboy riding a tarpon that will hang outside the first retail location for the Austin-based cooler brand, Yeti, at the foot of the Congress Avenue Bridge.

To Voyles, one of the most important aspects of his work is that no two signs are alike—there is no signature look. “It’s not a style, it’s a process,” he explains. “If my signs look handmade, it’s because they are.”

He deplores computer-controlled tools, such as CNC routers. In their place, he clamps sheets of aluminum and steel to his table, hand cuts them with a jigsaw or a pair of metal shears, and rivets them together. He designs and welds a sign’s internal skeleton—his favorite part, though its elegant form is invisible to anyone else—based simply on intuition about stress points. The neon comes last. He sends paper patterns to a professional “tube bender,” a specialist who heats and shapes glass to spec, and affixes the tubes only after the sign has been hung. “It seems inefficient, but there are just too many things that can go wrong and break the glass before it’s up in the air,” he says. “I’m usually there doing ladder ballet when the first guests show up—my clients joke that it’s part of the show.”

Photo: Matthew Johnson

The iconic Chuy’s sign on Barton Springs Road

Perhaps more than the process, it’s the stories behind the signs—involving vintage junk, lucky timing, and old friends—that give them their cool. One of Voyles’s favorites is the one about the SOUL sign at the Saint Cecilia. A dozen or so years ago, he spotted the ruins of a casino on the Texas-Louisiana line, topped by a partially dismantled sign that read LOU_S____ in big porcelain letters. He immediately thought of Lou Lambert, a popular Austin restaurateur, and stopped to buy the letters in case his friend ever needed a LOU’S sign. As it turned out, Lambert never did, but his sister, the hotelier Liz Lambert, bought the letters after Voyles spelled out SOUL in the window of his wife’s South Congress fashion boutique one year for South by Southwest. When everyone realized the finished sign was too big for the hotel bar where Lambert had envisioned it, the property’s groundskeeper suggested the pool. Now, Johnny Depp and Dave Grohl are the kind of regulars who lounge beneath it.

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-269

Austin’s Lucy’s Fried Chicken.

1 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-260

Perla’s Seafood & Oyster Bar on South Congress Avenue.

2 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-273

The sign at Home Slice Pizza.

3 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

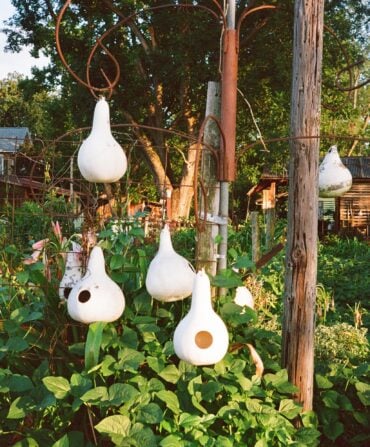

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-228

4 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-253

5 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-245

Austin’s Tesoro’s Trading Company.

6 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

neon-jungle-matthew-johnson-117

7 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

Inside his studio

8 of 9

Photo: Matthew Johnson

Voyles shapes metal by hand

9 of 9

Voyles’s own journey has been a string of accidents and unintended consequences. A child of Texas privilege (his grandfather struck it rich drilling for oil), he tried a more conventional path at first—studied English at Yale, settled in with a girl in California, started law school—but nothing stuck, so he hit the road. He spent much of the eighties roaming the vast spaces between California and Texas in a restored Land Cruiser, photographing old signs and amassing what he calls “the world’s biggest collection of vintage cowboy boots,” some 750 pairs. He saw in the boots and signs unappreciated forms of American folk art. “I became a dealer just to finance my collecting habit,” he says. “By 1992, I had a museum-grade boot collection, and I was starting to have a really good collection of signs.”

He eventually opened an antique shop in a small town outside of Austin and lived in the back—until a fire gutted the place in 1994. “All my clothes, my guitars, my guns, my family photos and papers—everything was destroyed,” he says. The boots, too. “They were hard as rocks, baked into permanence, toes turned up like the Wicked Witch of the West.” The next morning, as he surveyed the damage, he realized the only things he had left were the signs in the backyard. “Overnight, I was out of the boot business and in the sign business. It was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Photo: Matthew Johnson

The sign he created for Stag Provisions for Men anchors one of the busiest corners on South Congress Avenue

Neon signs were a lost art by then, replaced by the kind of cheap, Plexi-sheathed track letters that adorn strip malls across America. Voyles had no training in the sign trade, but he’d spent years dissecting and restoring vintage specimens. “I knew nothing about what I was doing, except what I learned from seeing how the old guys had done it,” he says. Soon enough, he scored an order for a sign at a curio shop on South Congress. “When we finished it and lit it up at night the first time, I literally jumped up in the air.”

He’s been chasing that same rush ever since. Some days he’s not sure he’ll keep doing commercial work. Maybe it would be better to ditch the deadlines and sell his signs as art, something he’s dabbled in over the years. But then, if he did that, he’d lose touch with his biggest project of all, the cumulative effect of his work on the city itself. As Austin has become an international brand, many longtime locals fear its famous weirdness could be lost. Voyles sees that as a dare to press on. “I don’t want to be one of those guys—Oh, it was better back when,” he says. “I’m going to make an Austin right now where people will say, Oh my God, remember when that guy was making those signs?